MARIA CALLAS: PUCCINI TOSCA AT THE GREEK NATIONAL OPERA IN 1942 AND 1943

27, 28, 30 August & 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30 September 1942

17, 21, 23, 25, 31 July 1943

A tribute to mark the centenary of her birth

Version Française: cliquer ICI

Maria Callas sang the role of Floria Tosca throughout her stage career, from 1942 to 1965. At the Greek National Opera, which was founded in 1939, she was able to benefit from exceptional working conditions to present this work in a new production when she was only 18, at a time when Greece was undergoing extremely harsh occupation conditions. Nicholas Petsalis-Diomidis’s indispensable book ‘The Unknown Callas – The Greek Years’ describes in detail how this new presentation of Tosca was staged, how Callas’s acting and singing fascinated from the outset, and how the production became a kind of benchmark for herself and for many other directors, so that twenty years later, and even more, it continued to influence new productions.

In a 1978 interview, actress Edwige Feuillère declared: ‘I admired Maria Callas at the Paris Opera in Tosca. She was extraordinarily beautiful and musical, but above all, for me as an actress, she was doing something extraordinary. I was at the Opera’s basket, and in the second act, where she is with Scarpia, I saw the precise moment when the idea of murder was germinating in her mind: you could see her eye stop on the knife on the table, the glass she was holding to her lips stop mid-stroke, and from a distance, you knew that this woman was going to kill Scarpia. It’s a marvellous piece of interpretative work, and it touched me deeply. For me, there was magic in it. Her vibrations were magical, there was a kind of exoticism in her timbre. All the beauty in her person was acquired beauty and elegance, and on top of that, there was all the incessant work on incomparable gifts, and the sum of all that is genius. This is a woman who, during her short trajectory, thought of nothing but recreating herself every day at every moment.‘

As Edwige Feuillère has pointed out, making the most of genius requires ceaseless work, and what is at first sight fascinating about Callas is that by 1942, she had already defined the exacting working methods that enabled her to do so, and which she would apply throughout her career. What’s even more fascinating is that, at such a young age, she was able to build a memorable interpretation of the character.

She had begun studying Tosca in 1938 with her teacher at the time, Maria Trivella, associate professor at the Athens Conservatory. At the instigation of tenor Ulysses Lappas, and after a favorable opinion from Elvira de Hidalgo, Maria Kalogeropoulou was officially chosen by the General Secretary of the National Theater Angelos Terzakis on July 10, 1942 to sing the role of Floria Tosca in a series of eighteen performances of Tosca under the direction of conductor Sotos Vassiliadis with stage director Dino Yannopoulos. The performances which were sold out, took place between August 27 and September 30, 1942, at the open-air Summer Theater in Athens’ Klafthmonos Square, a small venue with a modestly sized stage, with a premiere on August 27 for the version sung in Greek in Angelos Terzakis‘s translation, and on September 8 for the version sung in Italian (3 performances). Among the main characters, she was the only one to sing in both languages, and therefore had to learn the work and ensure all rehearsals in Greek and Italian. Mario was sung in Greek by Antonis Delendas and in Italian by Loudovikos Kourousopoulos. Baron Scarpia was sung in Greek by Titos Xirellis and Spyros Kalogeras (from September 24), and in Italian by Lakis Vassilakis. A revival with the same cast took place in 1943 for five performances in Greek ( July 17, 21, 23, 25 and 31 ).

Summer Theater at Klafthmonos Square (Athens)

Piano rehearsals for Tosca began in the hall of the National Theatre. According to Loudovikos Kourousopoulos, from the very first rehearsals, Callas was exceptional in her musicality and virtuosity. The two casts rehearsed alternately in Greek and Italian, and she had to be present at all times. When rehearsals with orchestra began at the theater in Klafthmonos Square, she always sang in full voice, without saving herself, as she would continue to do throughout her career. As her short-sightedness prevented her from seeing the conductor, she also attended rehearsals reserved for the orchestra alone, so as not to have to depend on the conductor’s gestures. In addition, Callas also studied the role in private rehearsals with conductor Sotos Vassiliadis and baritone Titos Xirellis, who was a renowned singer and composer. In particular, the latter taught her how to play the difficult scene in Act II between Scarpia and Tosca, which she would benefit from in all subsequent performances throughout her career.

At the premiere on Thursday August 27, 1942, the audience quickly realized that Maria Kalogeropoulou was someone to be noticed. According to Dino Yannopoulos, ‘When she came on stage, it was as if she took the audience by the scruff of the neck and said: Now, hear me!, I’ve something to say’. Antonis Kalaidzakis, a member of the chorus that night, says: ‘I remember that ‘Mario, Mario, Mario!’. It sent a shiver down your spine! It was a cry that came straight from the heart. That voice of hers was strange, there was a natural sob in it that projected you straight into an atmosphere of drama. The sound was a bit throaty, but attractively throaty, like the sound of a string instrument when not played absolutely true. It became crystal clear only on the high notes’.

After the aria ‘Vissi d’arte’ which she had to encore at each performance, the scene where she stabs Scarpia was impressive thanks to the ‘business’ devised by Yannopoulos and brilliantly performed by Maria. As Scarpia sat at his desk writing the safe-conduct Tosca has asked of him, she backed diagonally downstage toward the table. Stefanos Ciotakis, another member of the chorus, recalled: ‘On the table was the dagger, with the hilt toward her. She moved closer and closer to the table, walking rather unsteadily and we, knowing she could’nt see, were on tenterhooks. Would she put her hand on it or..?. But she, having measured her paces to perfection, arrived at the table and picked up the dagger with absolute precison, without even turning her head. That really froze the blood in our veins! ‘

Andonis Kalaidzakis remembers with emotion how, after Scarpia’s stabbing, Maria let the dagger drop from her hand and placed a candle on either side of the dead tyrant. The audience felt a thrill of excitement when Maria extracted the note clutched in the dead Scarpia’s hand. And then, she made her exit with another clever piece of staging by Dino Yannopoulos: walking at stage right, with her ermine cloak thrown over her shoulder and trailing on the floor, Maria turned round to look back at the dead Scarpia, while the curtain was drawn across from stage left to bring the scene to an end. Luschino Visconti acknowledged that he had admired that ingenious touch. Franco Zeffirelli was inspired by it, as was Benoit Jacquot much later (2001) in his film.

Her voice already had its essential properties. For the tenor Loudovikos Kourousoupoulos who was Mario in the three performances sung in Italian , ‘if you heard her sing without seeing her, you would think it was three different people singing. She had difficulties with the transitions from one register to another. When she hit a high note cleanly her voice didn’t wobble, but on an upward portamento it did. However, she had such a big vocal range and such warmth of tone, and above all her acting was so good, that those things were forgotten. The whole effect was so vibrantly alive that it made you jump out of your seat.’ This is confirmed by Nikos Papachristos, who was in the chorus: ‘We were baffled and taken aback by her voice. It had so many different tone colors that it lacked homogeneity: a high voice, a middle voice, and a low voice, all quite distinct. But there was a tremendous fluency throughout, and she acted so naturally on stage that you overlooked her vocal flaws.’

with Loudovikos Kourousopoulos

On Herbert Graf’s recommendation, Dino Yannopoulos was hired as principal director at the MET and remained there between 1946 and 1967. There, Callas met him again for his stage directions of Tosca (in 1956, 1958 and 1965) and of Norma in 1956. The excerpts from the end of Act II filmed during the Ed Sullivan Show on November 25, 1956 (dir: Dimitri Mitropoulos with George London, Scarpia) give us an idea of his staging, with particularly, at the very end, Callas’ famous exit with her cloak trailing on the floor.

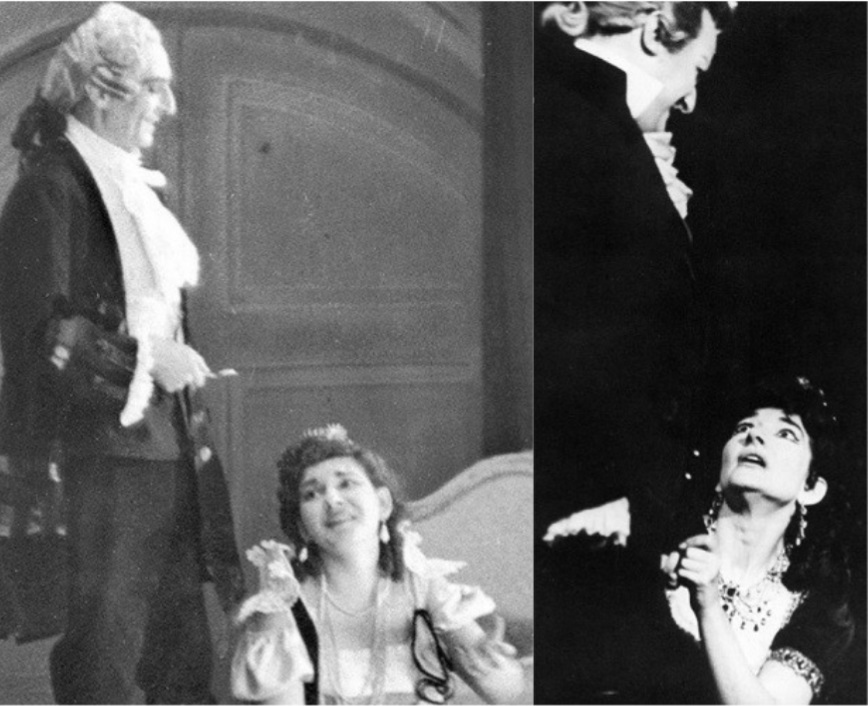

The comparative photographs below, taken on stage during the rehearsals of Act II in 1942 in Athens with stage director Dino Yannopoulos, and in 1964 in London (Covent Garden) under the direction of Franco Zeffirelli, show astonishing visual similarities between the two productions taken at the very beginning (in 1942, she was not yet 19) and near the end of Maria Callas’ stage career. Her very last public performance of an opera was Tosca at Covent Garden on July 5, 1965.

On the pictures below: Left: Athens Opera 1942; Right: London Covent Garden 1964

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

______

Act II Tosca/Mario – Left: with Antonis Delendas ; Right: with Renato Cioni

______

Act II – ‘Vissi d’arte’

______

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

N.B. Some sources claim that Maria Callas sang Tosca in Athens in July 1941 to replace an ailing singer. This information is incorrect. There were no performances of Tosca at the National Theater in 1941. It was only in 1942, with the new production, that Tosca began to be performed there.

2 réponses sur « MARIA CALLAS: PUCCINI TOSCA AT THE GREEK NATIONAL OPERA IN 1942 AND 1943 »

Thank you, C&A, for your well-researched article to honour the great Maria Callas on the occasion of her upcoming birthday centenary on December 2nd this year. Notwithstanding the by no means insignificant role Tosca had played throughout her entire career (not to mention perhaps her most famous commercial recording, the 1953 EMI/UK Columbia Tosca conducted by Victor de Sabata), her extraordinary musical and interpretive gifts are best manifested in Classical and early Romantic (bel canto) operas as well as early to middle period Verdi. Norma, Violetta, Medea, Lucia di Lammermoor, Anna Bolena, Lady Macbeth are much more representative of her achievements and greatness.

You are quite right. Herself was not very fond of Tosca, but the aim here is not Tosca in the first place, but to put forward how, fascinatingly, she was able at a very early stage of her career to set up her stringent working methods with conductors, partners and stage directors and to built a memorable interpretation.

In 1942, the opera houses were giving one different opera every day, with hardly any rehearsal (compare with the debut of Astrid Varnay as Sieglinde at the MET in December 1941!), but the principle of series of performances of a single opera, which has now become very common, was quite rare then. So, she benefited from this, too, because she had time (three weeks) to rehearse the production.

All this combined had a great influence on her future career, and of course helped her for the great parts that were to become the core of her repertoire and as you mention are much more representative of her achievements and greatness.