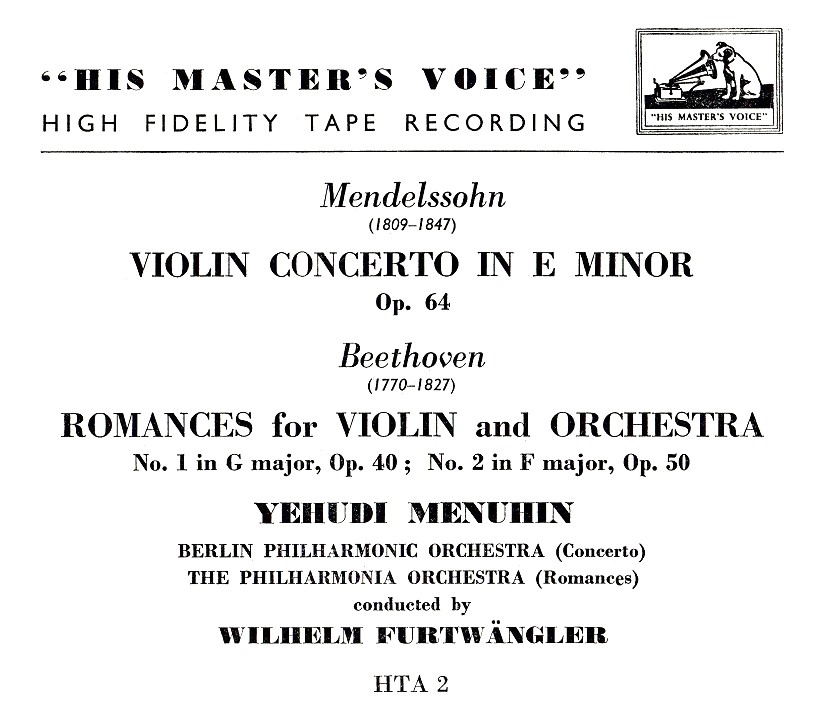

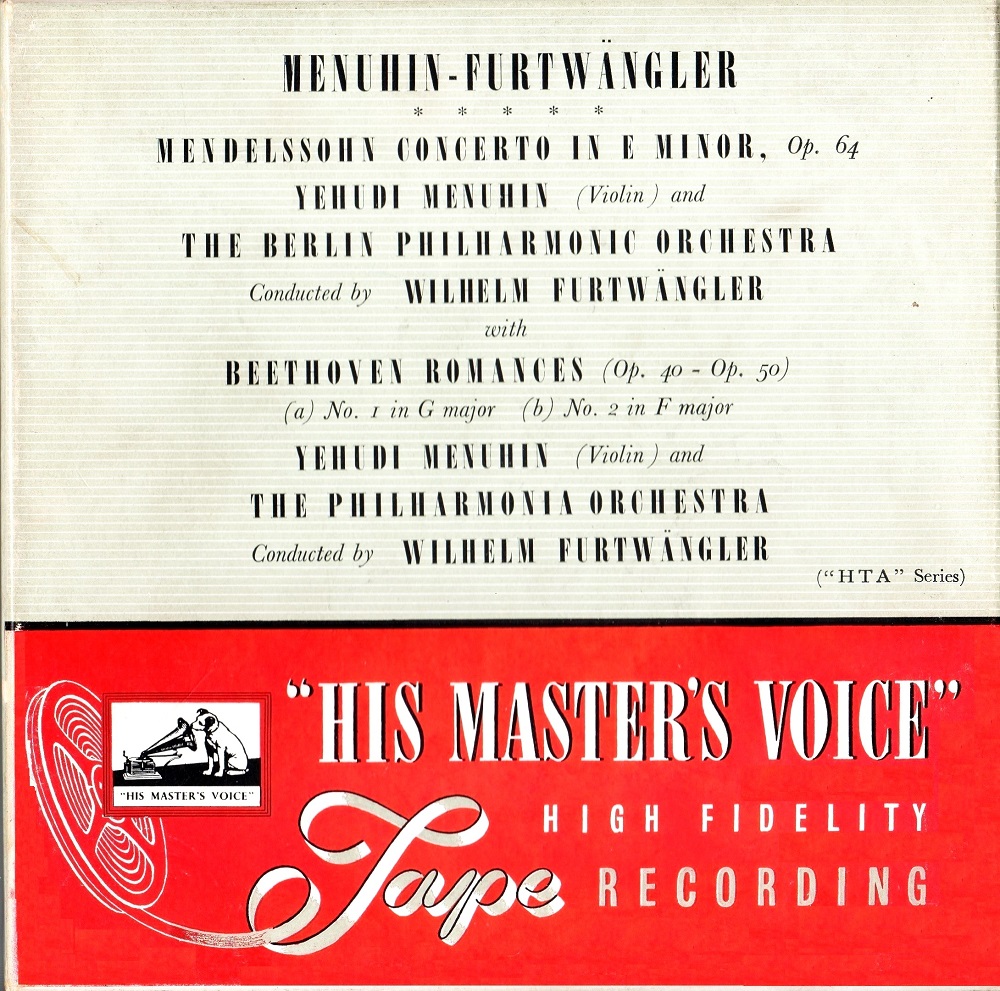

Étiquette : Bande/Tape

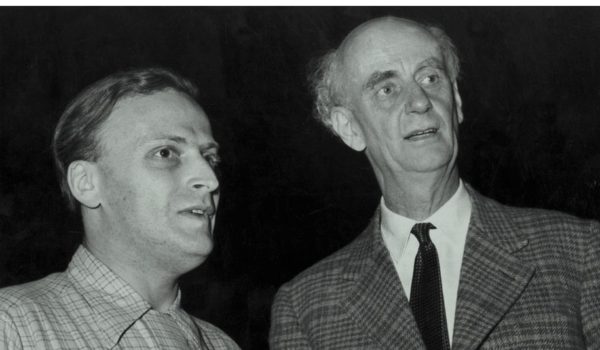

Yehudi Menuhin & Wilhelm Furtwängler

Mendelssohn: Concerto Op.64 Berliner Philharmoniker (BPO)

Berlin Jesus-Christus Kirche – 25 & 26 Mai 1952

Eng: Robert Beckett

______

Beethoven: Romances Op.40 & 50 Philharmonia Orchestra

London Kingsway Hall – 9 April 1953

Prod: Lawrence Collingwood & David Bicknell – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTA 2

Menuhin et Furtwängler ont joué pour la première fois ensemble le Concerto Op.64 de Mendelssohn le 29 septembre 1949 au Royal Albert Hall de Londres avec les Wiener Philharmoniker.

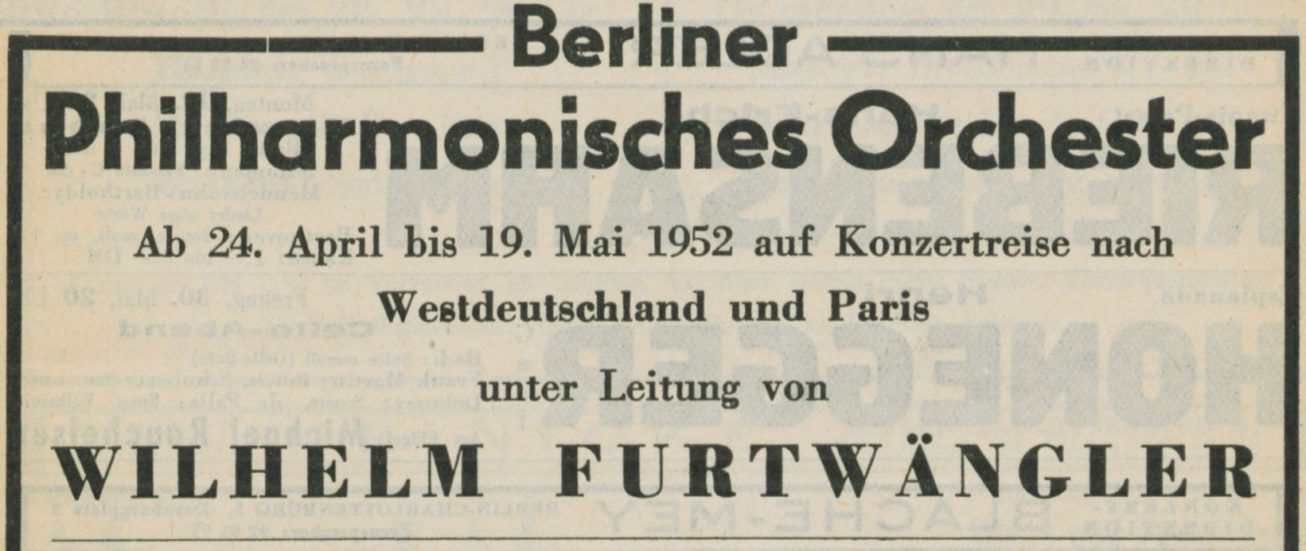

Avec le Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) de retour d’une tournée qui s’est déroulée entre le 24 avril et le 19 mai 1952, ils ont joué ce Concerto au Titania Palast de Berlin le 24 mai avant de l’enregistrer les 25 et 26 à la Jesus-Christus Kirche, salle utilisée habituellement par la Deutsche Grammophon et la RIAS.

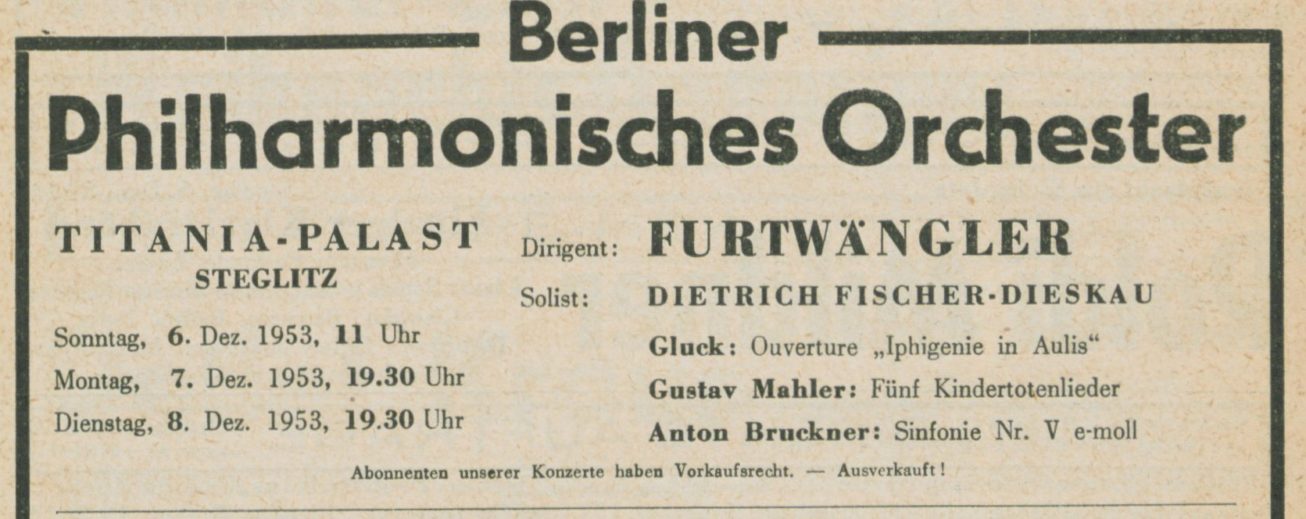

C’était la première fois qu’après la guerre EMI enregistrait Furtwängler à Berlin. Il y eut ensuite un autre enregistrement berlinois, à savoir l’Ouverture de ‘Leonore II’ de Beethoven les 4 et 5 avril 1954 à la Musikhochschule, avec cette fois une équipe d’enregistrement allemande (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), peut-être un test annonciateur d’un changement de politique discographique qui n’a malheureusement pas pu se concrétiser en raison du décès du chef d’orchestre. On peut penser en effet qu’EMI aurait souhaité enregistrer l’année suivante avec Furtwängler et le BPO les Kindertotenlieder de Mahler avec Fischer-Dieskau (l’œuvre a été jouée à Berlin en décembre 1953, et un enregistrement à Londres en mars 1954 avec le Philharmonia a été annulé) ainsi que le Deutsches Requiem de Brahms avec Grümmer et Fischer-Dieskau, deux projets qui ont été confiés in fine à la direction de Rudolf Kempe.

Menuhin and Furtwängler performed Mendelssohn’s Concerto Op.64 together for the first time on 29 September 1949 at London’s Royal Albert Hall with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With the Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) on their return from a tour that lasted from 24 April to 19 May 1952, they played this Concerto at the Titania Palast in Berlin on 24 May before recording it on 25 and 26 May at the Jesus-Christus Kirche, a venue known as being used by Deutsche Grammophon and RIAS.

It was the first time after the war that EMI recorded Furtwängler in Berlin. There was later another recording in Berlin, Beethoven’s Overture ‘Leonore II’ on April 4 and 5 1954 at the Musikhochschule, this time with a German recording team (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), maybe a test which heralded a change in recording policy that unfortunately could not materialise due to the conductor’s death. Indeed, one might think that EMI would have liked to record the following year with Furtwängler and the BPO Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with Fischer-Dieskau (the work was performed in Berlin in December 1953, and a recording in London in March 1954 with the Philharmonia had been cancelled) as well as Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem with Grümmer and Fischer-Dieskau, two projects that were ultimately entrusted to Rudolf Kempe.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

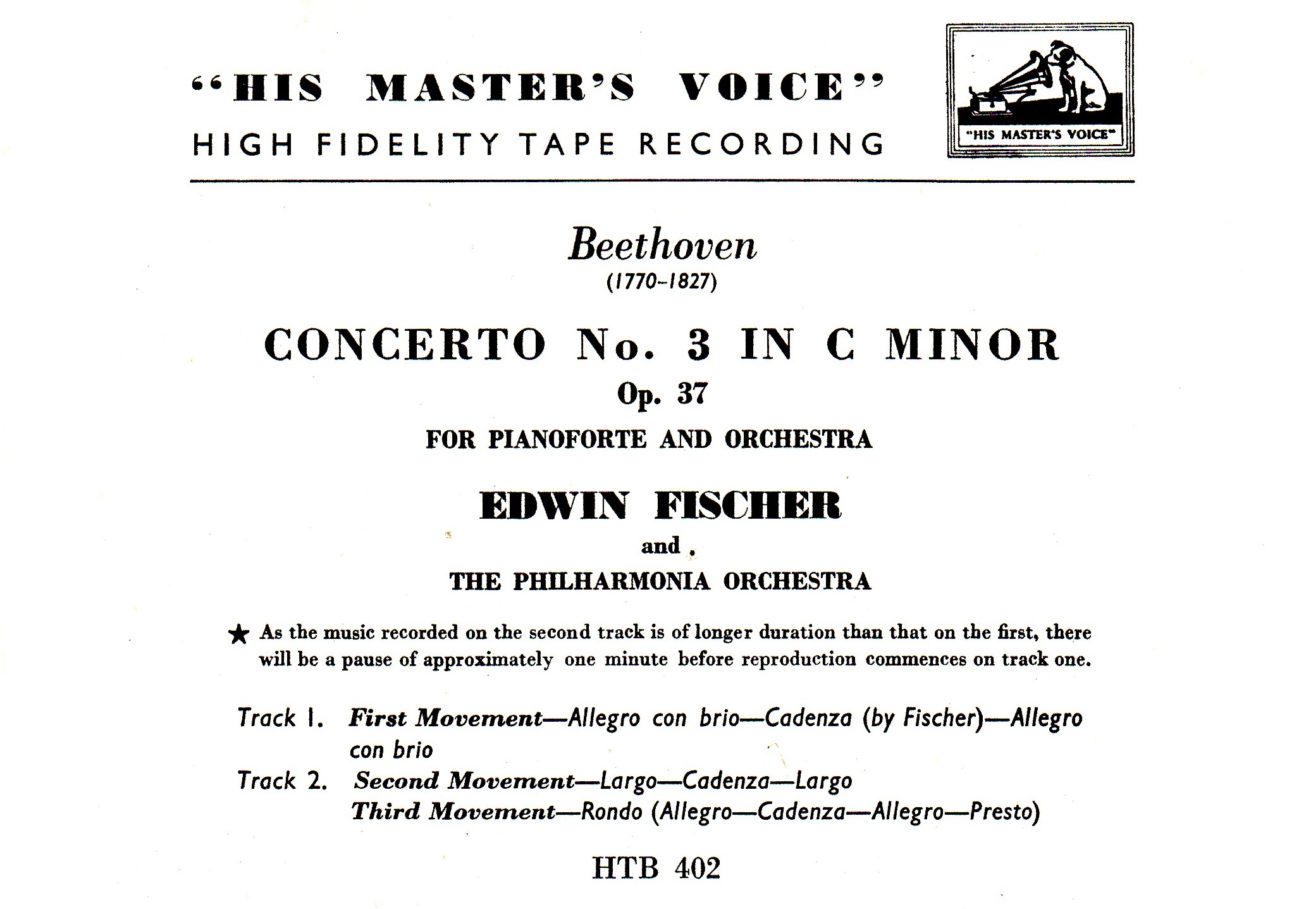

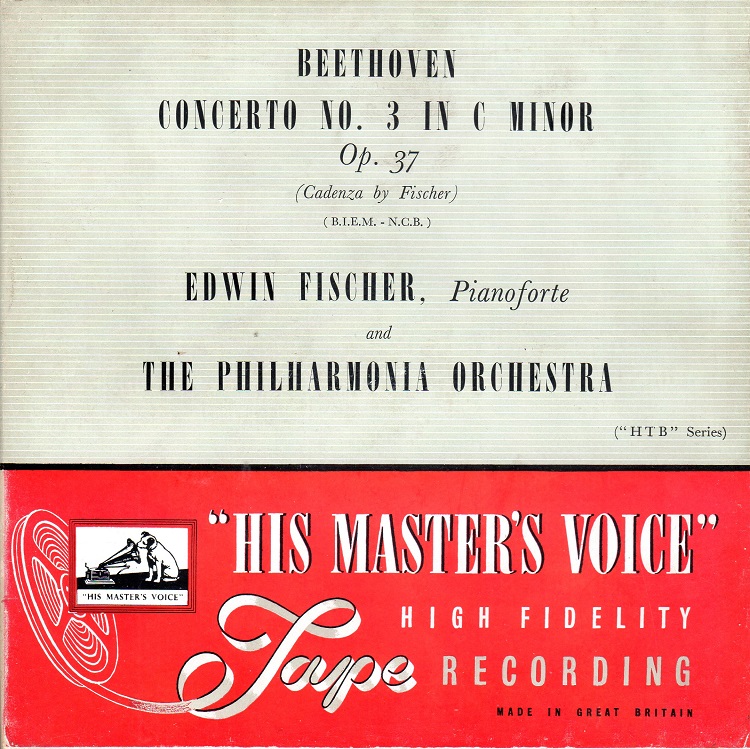

Fischer – Philharmonia Orchestra – Beethoven Concerto n°3 Op. 37

London Kingsway Hall – 7 & 14 mai 1954

Prod: Walter Jellinek & Alec Robertson – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTB 402

Nous vous avons déjà proposé cet enregistrement à partir de la même source. En voici le lien:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

La bande étant selon le standard CCIR, il a fallu tenir compte de la différence entre les courbes d’égalisation de la bande (CCIR) et le magnétophone (NAB) sur laquelle elle était lue. A l’époque, cette égalisation n’a pu être faite que de manière approximative et le son obtenu accentuait les duretés de la prise de son, surtout sur l’orchestre. Avec une meilleure égalisation, le son est maintenant plus musical, sans que l’on perde pour autant les détails de l’interprétation.

We have already offered you this recording from the same source. Here is the link:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

As the tape was in the CCIR standard, it was necessary to take into account the difference between the equalisation curves of the tape (CCIR) and of the tape recorder (NAB) on which it was played. At the time, this equalisation could only be done approximately and the sound obtained accentuated the harshness of the recording, especially on the orchestra. With better equalisation, the sound is now more musical, without losing any of the details of the performance.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

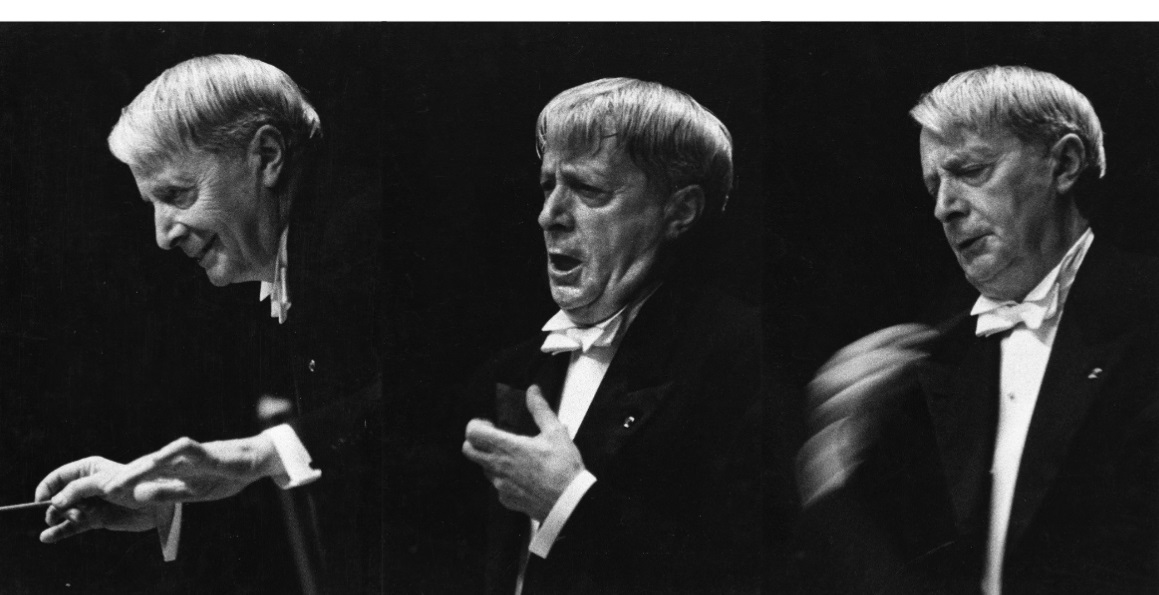

Charles Munch Ravel

Orchestre National de la RTF (ON)

Tombeau de Couperin

Festival de Besançon – Théâtre Municipal 2 Septembre 1954

______

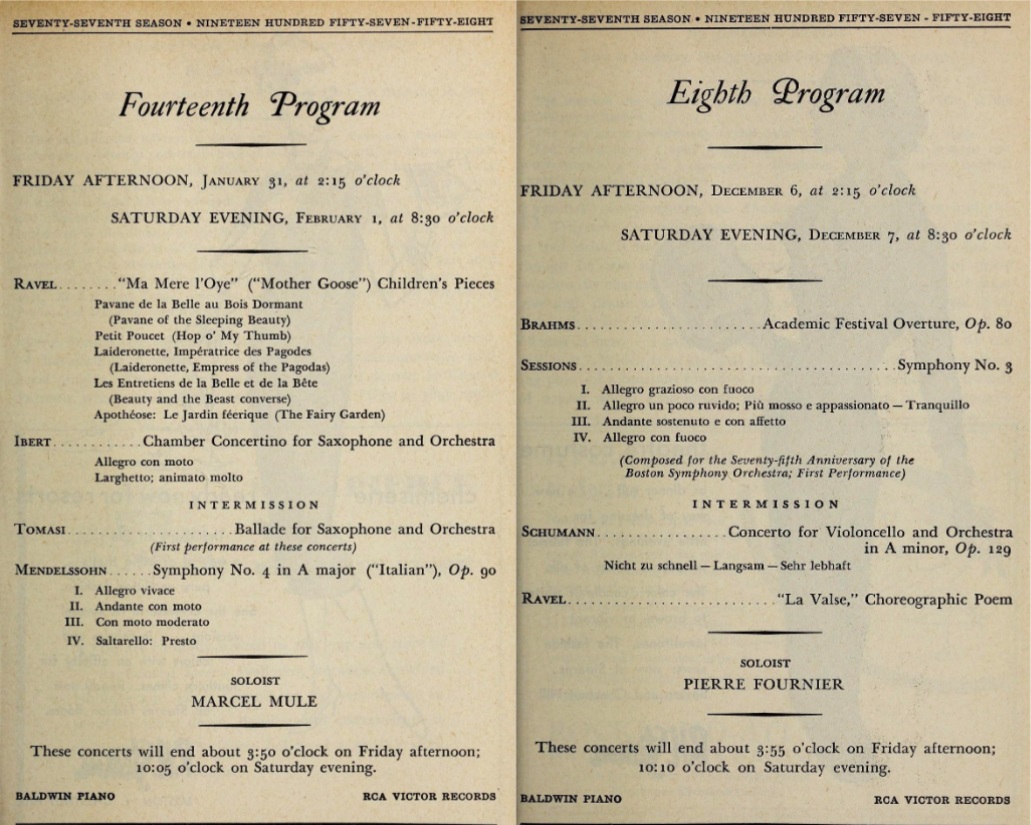

Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)

Ma Mère l’Oye (suite)

Boston Symphony Hall January 31, 1958

La Valse

Boston Symphony Hall December 6, 1957

La Valse Répétition/Rehearsal

Boston Symphony Hall February 12, 1950

______

Bonus: Charles Munch – Interview (1964)

Source Bande/Tape : 2 pistes/19 cm/s / 2 tracks 7.5 ips MONO

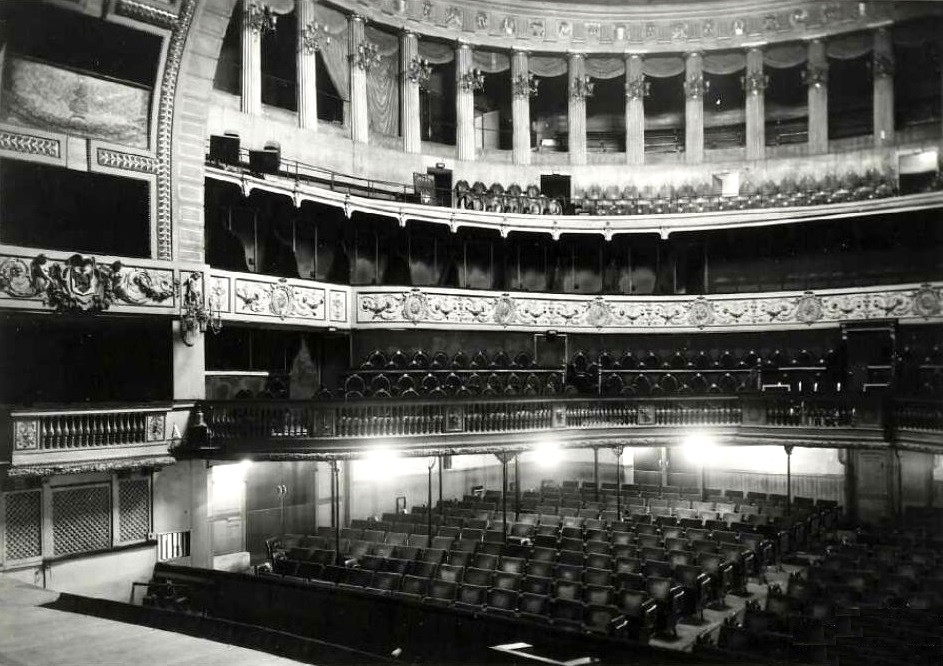

Charles Munch a dirigé 24 fois le ‘Tombeau de Couperin avec le BSO entre 1950 et 1961, mais il n’en a pas laissé de version discographique. On en connaît un enregistrement public du 17 octobre 1953 avec le BSO, publié par WHRA, dans lequel les variations de tempo peuvent paraître exagérées. Cette version avec l’Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF), souvent appelé ‘l’ON’ provient du concert d’ouverture du Septième Festival de Besançon 1954, donné au Théâtre Municipal. On possède peu d’enregistrements réalisés dans ce Théâtre conçu par l’architecte Claude-Nicolas Ledoux – il a été inauguré en 1784 -et renommé pour son acoustique. En effet, il a été entièrement détruit par un incendie en avril 1958, et s’il a été reconstruit, ce fut très rapidement pour assurer une continuité.

A Boston, Munch n’a donné que 6 fois la Suite de ‘Ma Mère l’Oye’, en janvier-février 1958, mais il en a cependant réalisé un enregistrement discographique le 19 février.

La Valse a été jouée 56 fois par Munch et le BSO entre 1950 et 1966, et avec cet orchestre, il l’a enregistré trois fois pour le disque (11 avril 1950, 5 décembre 1955 et 26 mars 1962). L’extrait de la répétition de 1950 nous montre quel niveau d’intensité Munch pouvait atteindre. L’enregistrement de concert du 6 décembre 1957 est semble-t-il inédit.

Munch Festival de Strasbourg 1954

Charles Munch conducted the ‘Tombeau de Couperin’ 24 times with the BSO between 1950 and 1961, but he left no commercial recording of it. We know of a public recording of October 17, 1953 with the BSO, published by WHRA, in which the tempo variations may seem exaggerated. This version with the Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF), often called ‘l’ON’, comes from the opening concert of the Seventh Besançon Festival 1954, given at the Théâtre Municipal. Few recordings made in this Theatre, designed by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux – it was inaugurated in 1784 – and renowned for its acoustics, have survived. In fact, it was completely destroyed by fire in April 1958, and if it was rebuilt, it was very quickly to ensure continuity.

In Boston, Munch performed the Suite from ‘Ma Mère l’Oye’ only 6 times, in January-February 1958, although he did make a commercial recording of it on February 19.

‘la Valse’ was performed 56 times by Munch and the BSO between 1950 and 1966, and with this orchestra he recorded it three times for disc (April 11, 1950, December 5, 1955 and March 26, 1962). The excerpt from the 1950 rehearsal shows us the level of intensity Munch could achieve. The concert recording of December 6, 1957 appears to be unpublished.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

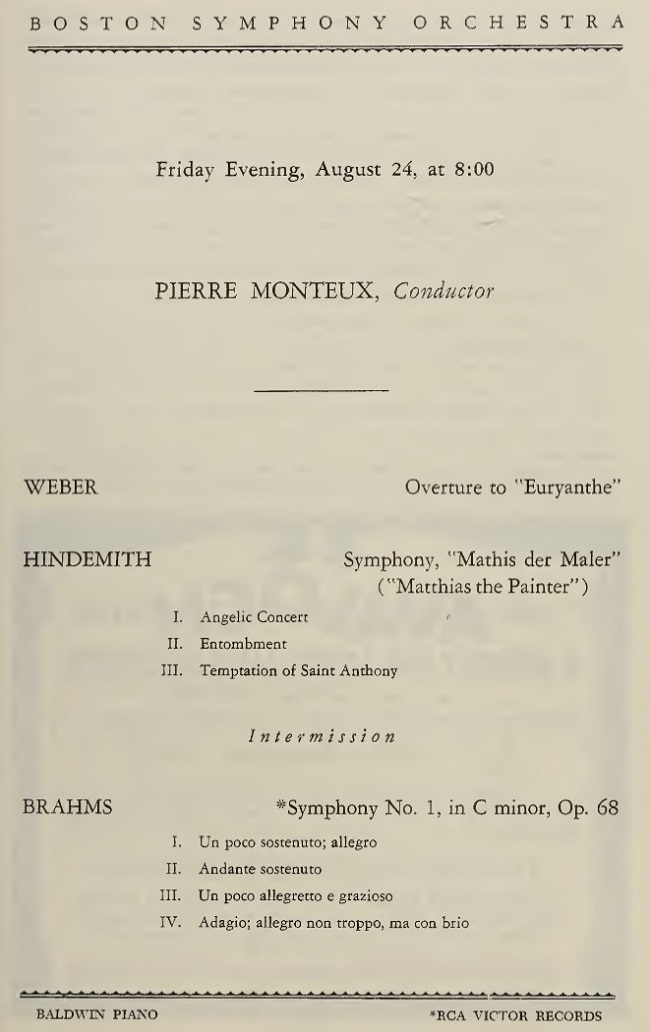

Brahms Symphony n°1 Op.68

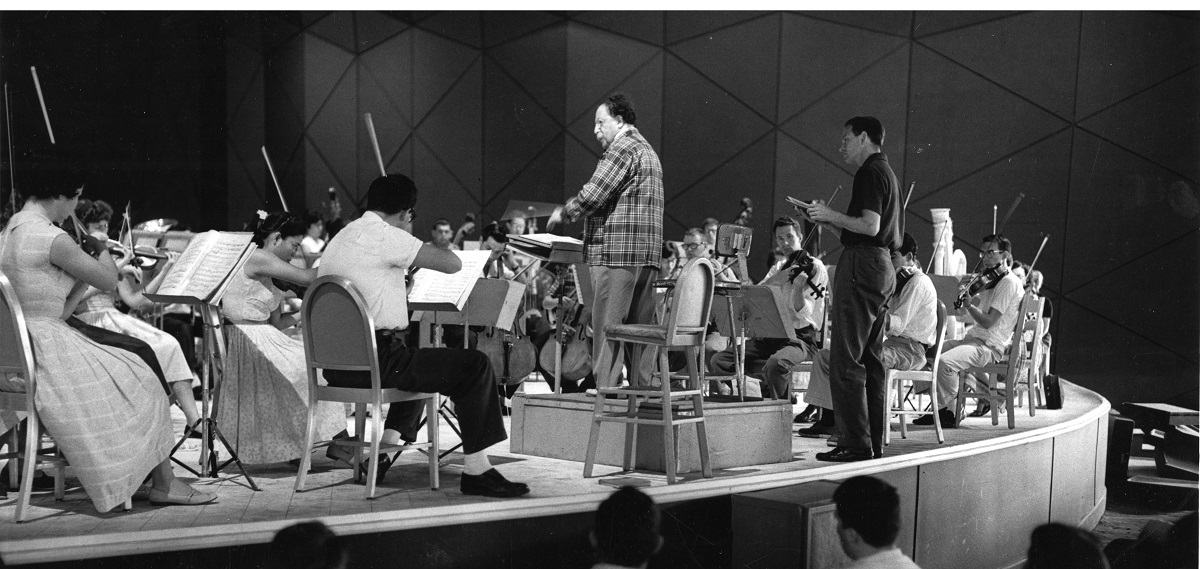

Pierre Monteux – Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)

Berkshire Festival – Tanglewood Music Shed August 24, 1962

Source: Bande/Tape: 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips STEREO

Pierre Monteux n’aimait pas être considéré comme un spécialiste de musique française, même s’il y excellait. Ce qui l’intéressait, c’était de pouvoir diriger un répertoire aussi vaste que possible, comme le montre sa discographie à condition de prendre en compte les enregistrements en public.

Une anecdote bien connue concerne le Metropolitan Opera de New York (MET). On ne lui permettait en effet d’y diriger que des opéras français et, de la même façon, les chefs italiens invités au MET devaient aussi se limiter aux opéras italiens. Un jour, il rencontra Dimitri Mitropoulos qui lui dit que, comme il était grec, et qu’il n’y avait pas d’opéra grec pouvant servir de référence, il pouvait y diriger tous les répertoires!

Monteux aimait beaucoup diriger Brahms. Au Festival de Berkshire 1962, il a donné cette interprétation chaleureuse de la ‘Première’ de Brahms, œuvre qu’il n’a pas enregistrée pour le disque.

Il faut dire que c’était une occasion très spéciale: d’une part, les deux jours suivants, Charles Munch a donné ses deux derniers concerts en tant que directeur musical du BSO, à savoir le 25 août, Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique, Debussy La Mer et Ravel Daphnis et Chloé (Suite n°2); et le 26 août, pour le dernier concert du ‘Berkshire Festival’, Copland Quiet City et Beethoven Symphonie n°9 Op.125; et d’autre part, le départ de Charles Munch signifiait aussi celui de Richard Burgin (1892–1981), qui était le ‘Concertmaster’ du BSO depuis 1920 après avoir été nommé par Monteux qui était alors Directeur Musical du BSO (1919-1924). Joseph Silvestein l’a remplacé dès le début de la saison 1962-1963. Burgin restera ‘Associate Conductor’ jusqu’en 1966.

Richard Burgin & Pierre Monteux Tanglewood 1962: les derniers concerts ensemble / the last concerts together

Pierre Monteux didn’t like to be considered a specialist in French music, even if he excelled at it. What interested him was being able to conduct as wide a repertoire as possible, as his discography shows, if you include live recordings.

A well-known anecdote concerns New York’s Metropolitan Opera (MET). He was only allowed to conduct French operas there, and similarly, Italian conductors invited to the MET had to restrict themselves to Italian operas. One day, he met Dimitri Mitropoulos, who told him that, since he was Greek, and there was no Greek opera to refer to, he could conduct all repertoires there!

Monteux loved conducting Brahms. At the 1962 Berkshire Festival, he gave this warm performance of Brahms’s ‘First’, a work of which he made no commercial recording.

It was in fact a very special occasion: on the one hand, on the following two days, Charles Munch gave his last two concerts as Music Director of the BSO: on August the 25th, Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique, Debussy La Mer and Ravel Daphnis et Chloé (Suite n°2); and on August the 26th, for the last concert of the ‘Berkshire Festival’, Copland Quiet City and Beethoven Symphony n°9 Op.125; and on the other hand, Charles Munch’s departure also meant that of Richard Burgin (1892-1981), who had been the BSO’s ‘Concertmaster’ since 1920, having been appointed by Monteux, who was then Music Director of the BSO (1919-1924). Joseph Silvestein replaced him at the start of the 1962-1963 season. Burgin remained Associate Conductor until 1966.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

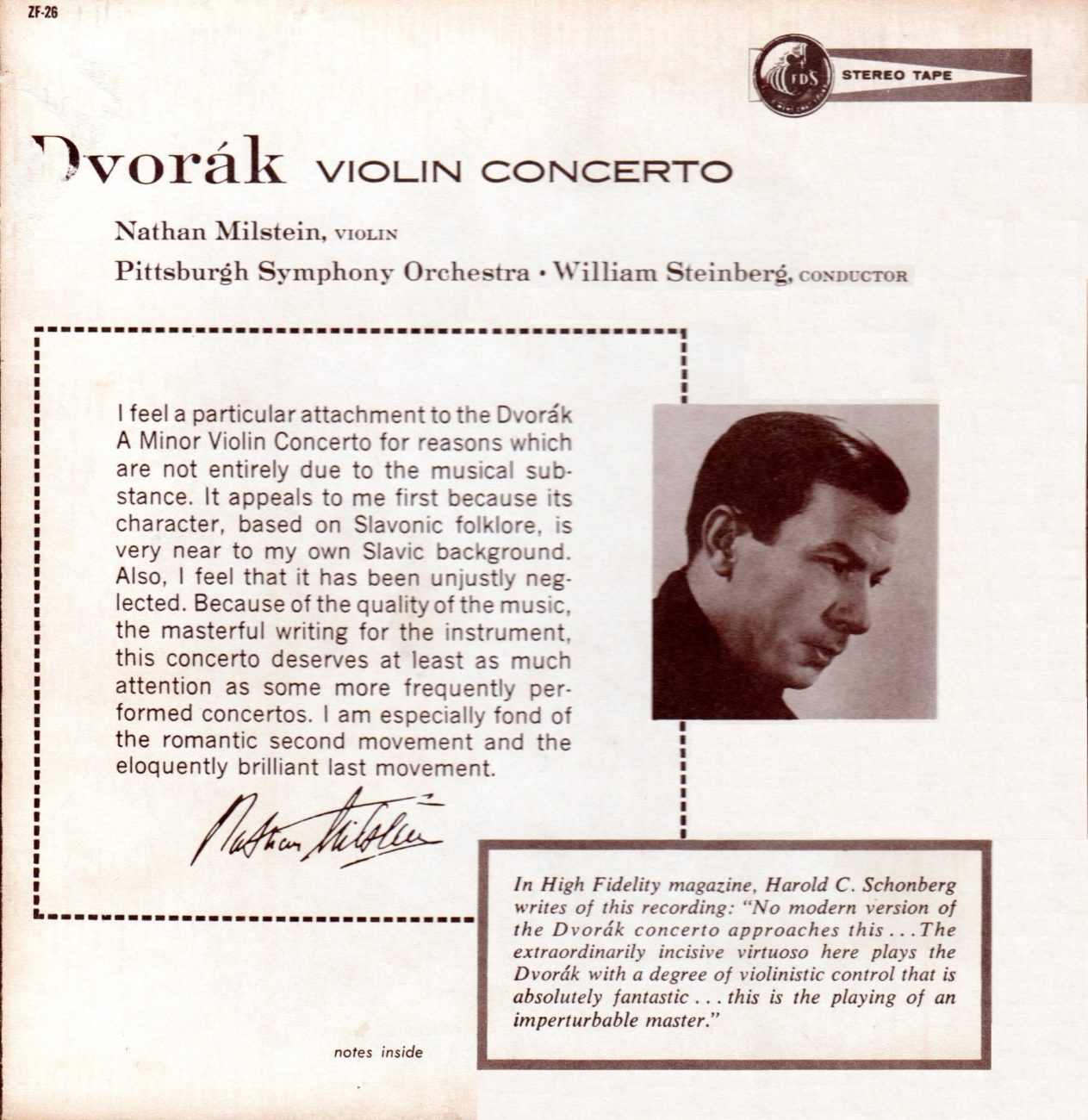

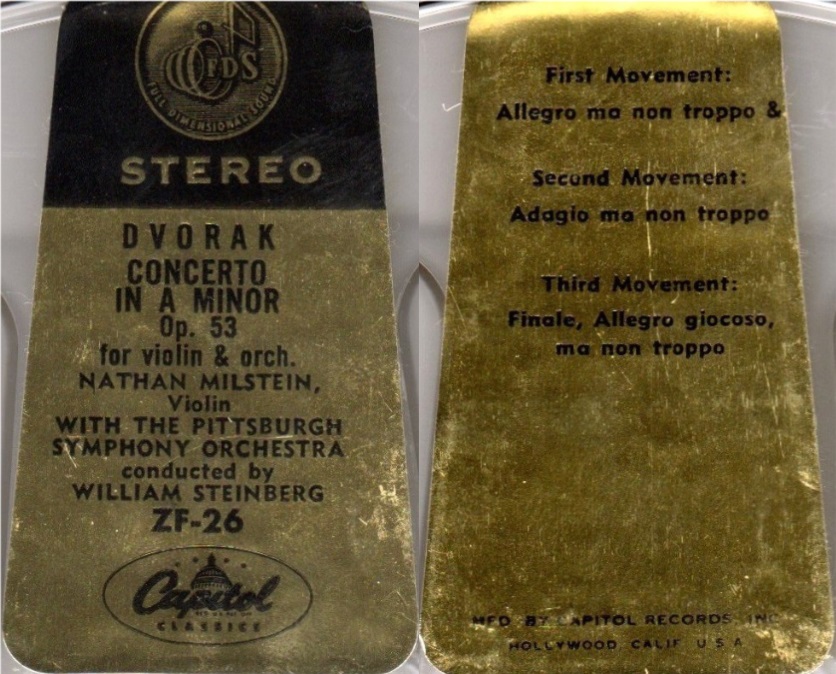

Dvořák Violin Concerto Op.53

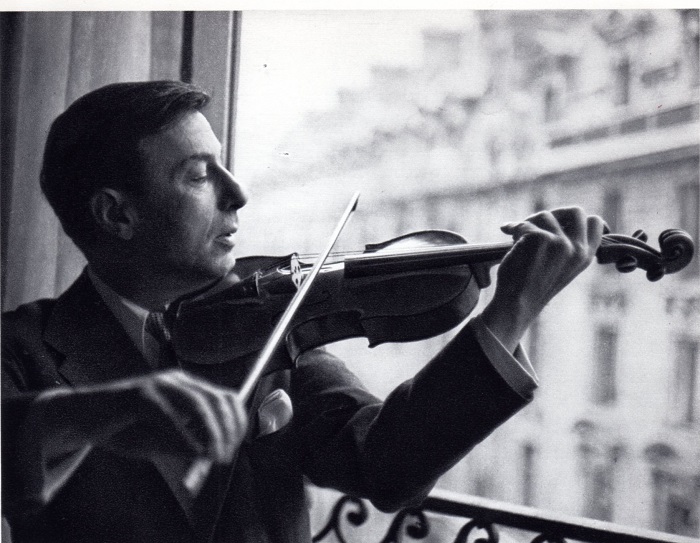

Nathan Milstein

William Steinberg Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

Pittsburgh Syria Mosque – April 16 & 17, 1957

Source Bande/Tape Capitol ZF-26: 2 pistes/19 cm/s / 2 tracks 7.5 ips STEREO

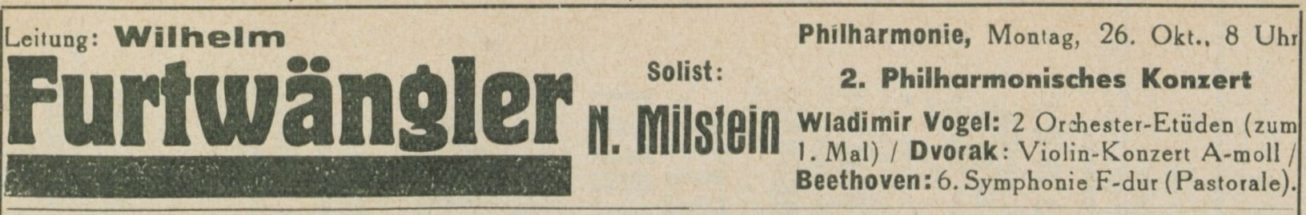

C’est en 1930 que Nathan Milstein et William Steinberg (Hans Wilhelm Steinberg) ont joué ensemble pour la première fois. Les enregistrements qu’ils ont faits ensuite (Concertos de Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Dvořák, Glazounov, Mendelssohn, et Tchaïkovsky) témoignent de la qualité de leur compréhension réciproque de la musique.

Nathan Milstein jouait ce concerto depuis le début des années trente, et c’était l’un de ses préférés. Dans son livre « From Russia to the West », il parle de certaines de ses premières interprétations de cette œuvre:

‘Gregor Piatigorsky, à l’époque premier violoncelle de l’orchestre de Furtwängler, le Philharmonique de Berlin, nous a présentés. Après mes concerts réussis à Vienne, mon agent Paul Bechert m’a garanti que je jouerais bientôt avec le BPO sous la direction de Furtwängler lui-même. Et c’est ce qui s’est passé : Furtwängler m’a demandé de jouer le Concerto de Dvořák. Je n’aurais jamais pu imaginer que le Dvořák aurait particulièrement intéressé Furtwängler, qui composait lui-même de la musique complexe (et peu attrayante). Mais il s’est avéré qu’il connaissait parfaitement l’œuvre.

Jeune musicien effronté, j’avais l’habitude de faire une coupure dans le mouvement lent du concerto. Furtwängler n’était pas d’accord. Un autre géant de la musique allemande, Richard Strauss, a réagi de la même manière à cette coupure que j’avais faite dans le Dvořák.

Une fois, j’ai dû jouer le concerto à Francfort. Mon agent m’a dit : « Vous allez jouer avec Strauss, j’espère que cela ne vous dérange pas ». Il ne m’est pas venu à l’esprit qu’il parlait du célèbre Richard Strauss, qui était déjà considéré comme un classique à l’époque où je fréquentais l’école de musique d’Odessa, où l’on jouait souvent Mort et Transfiguration et Salomé. En fait, Strauss était plus célèbre dans notre pays que Brahms. Au moment du concert de Francfort, j’étais persuadé qu’il était mort. Je n’ai donc pas prêté attention aux paroles de mon agent concernant le chef d’orchestre qui était prévu – Strauss, Schwartz, quelle différence cela faisait-il?

Lorsque j’ai vu le chef d’orchestre et que j’ai réalisé qu’il s’agissait de Richard Strauss, j’ai été presque choqué. J’étais certain que Strauss ne connaîtrait pas le concerto de Dvořák – comment une telle musique pourrait-elle l’intéresser ? Mais dès le début de la répétition, dès la première minute, je me suis rendu compte qu’il en connaissait chaque note! Et bien sûr, j’ai fait la même coupure dans le mouvement lent, en oubliant de le prévenir. Soudain, il a dit d’un ton de reproche : « Mais c’est la plus belle partie du Concerto« .

Ils l’ont donc dit tous les deux, Strauss et Furtwängler ! Et naturellement, ils avaient raison. Depuis lors, j’ai toujours joué – et enregistré – le Concerto sans coupures!’

Furtwängler Milstein BPO Berlin 25 & 26 Oktober 1931

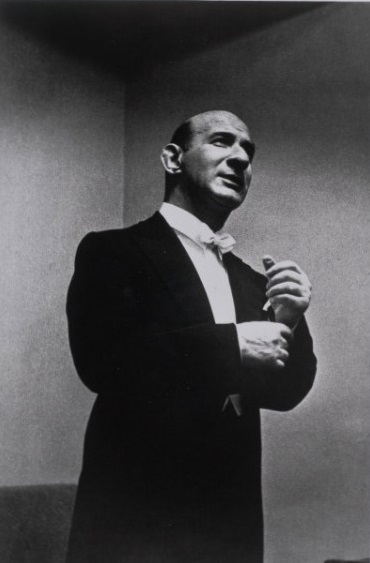

William Steinberg

It was in 1930 that Nathan Milstein and William Steinberg (Hans Wilhelm Steinberg) performed together for the first time. The recordings that they later made (Concertos by Beethoven, Brahms, Bruch, Dvořák, Glazounov, Mendelssohn,and Tchaïkovsky) bear witness to the quality of their mutual musical understanding.

Nathan Milstein performed this Concerto since the early thirties, and it was one of his favourites. In his book ‘From Russia to the West’, he talks about some of his early perfomances of this work:

‘Gregor Piatigorsky, at the time first cello in Furtwängler’s orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, introduced us. After my successful concerts in Vienna, my agent Paul Bechert guaranteed me I will shortly play with the BPO with Furtwängler himself conducting. And so it happened, and Furtwängler asked me to play the Dvořák Concerto. I could not have imagined that the Dvořák would have particularly interested Furtwängler, who composed complex (and not very attractive) music himself. But it turned out he knew the composition note-perfect.

Being a young, brash musician, I used to make a cut in the slow movement of the concerto. Furtwängler did not approve. Another giant of German music, Richard Strauss, reacted the same way to this cut of mine in the Dvořák.

One time, I had to play the Concerto in Frankfurt. My manager told me: ‘You will be performing with Strauss, I hope you don’t mind’. It never occured to me that he was talking about the famous Richard Strauss, who had been considered a classic back when I was at music school in Odessa, where in those years Death and Transfiguration and Salome were often performed. In fact, Strauss was more famous in our country than Brahms. By the time of the concert in Frankfurt, I was sure he had died. So, I paid no attention to the manager’s words about the prospective conductor – Strauss, Schwartz, what difference did it make?

When I saw the maestro and realized that it was the Richard Strauss, I was almost in shock. I was certain that Strauss would not know the Dvořák Concerto – how could music like that interest him? But as soon as the rehearsal began, from the first minute, I realized that he knew it, every note of it! And of course I made the same cut in the slow movement, forgetting to warn him. Suddenly he said reproachfully, ‘But it is the most beautiful part of the Concerto!’

So, they both said it, Strauss and Furtwängler! And naturally, they were right. Since then, I have always played – and recorded – the Concerto without cuts!’

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment