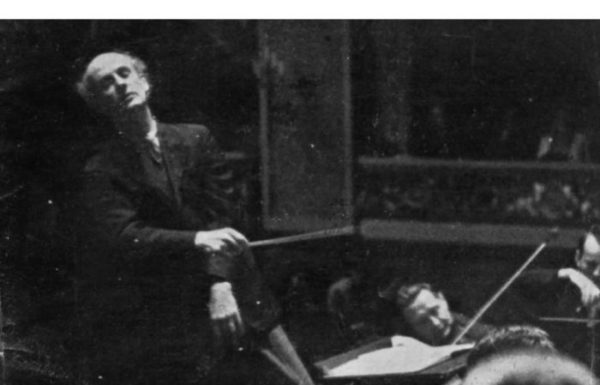

Furtwängler – Brahms: Symphonie n°2 London Philharmonic Orchestra

Kingsway Hall – 20,22,24 & 25 March 1948 Prod: Victor Olof – Eng: Kenneth Wilkinson

Source: 33t/LP Decca ACL 50 (1959)*

Entre le 29 février et le 25 mars 1948, Furtwängler a donné une série de dix concerts avec le LPO dont six à Londres et quatre en tournée, avec notamment au programme les quatre symphonies de Brahms (la Deuxième a été jouée à Londres le 11 mars), le dernier concert, le 25 mars,ayant été consacré à la Neuvième de Beethoven. Quatre jours d’enregistrement ont été consacrés à cette Deuxième (20,22,24 et 25 mars), et le 26 mars, Furtwängler a enregistré pour EMI l’Immolation de Brünnhilde avec Kirsten Flagstad et le Philharmonia, avant de partir pour une série de concerts à Buenos Aires.

La reproduction du son de cet enregistrement de la Deuxième de Brahms a toujours été problématique, et ce pour plusieurs raisons. John Culshaw raconte dans son livre ‘Putting the Record Straight’ que Furtwängler aurait refusé l’utilisation de plusieurs microphones, si bien que la captation a eu lieu avec un seul microphone, ce qui était cependant une pratique relativement courante à l’époque. Par exemple, DGG a enregistré de cette façon à la Jesus Christ Kirche de Berlin en 1953 la Symphonie n°4 de Schumann avec Furtwängler et le BPO. Toutefois Decca n’utilisait pas cette méthode et il se peut que cela ait créé des difficultés, car la prise de son par Decca de cette symphonie de Brahms manque peut-être un peu de présence, quoique, lors de la sortie des 78tours, EMG Letter a loué la chaleur du son dans l’excellente acoustique de Kingsway Hall. A ceci s’ajoute le problème lié à la définition de la courbe de gravure FFRR utilisée par Decca pour les microsillons (le disque LXT 2586 est paru en juin 1951), car l’éditeur en a utilisé plusieurs versions au début des années cinquante sans que les disques renseignent l’exacte version mise en œuvre.

La réédition de 1959 dans la collection ‘Ace of Clubs’ (ACL 50) permet de lire ce microsillon avec la bonne courbe FFRR, et de restituer la prise de son avec son équilibre tonal d’origine. On notera que lire ce disque avec la courbe RIAA qui est devenu un standard depuis les années 80, donne un son déséquilibré, et on perd beaucoup de l’interprétation, notamment avec un manque de graves qui affecte beaucoup la dynamique.

La prise de son est très musicale, et reproduit l’ambiance de salle du Kingsway Hall. On perçoit bien le son caractéristique de Furtwängler, ainsi que le fait que l’orchestre n’a pas la profondeur de son du BPO ou du WPO, ce qui n’est pas forcément un inconvénient pour cette œuvre.

Kingsway Hall

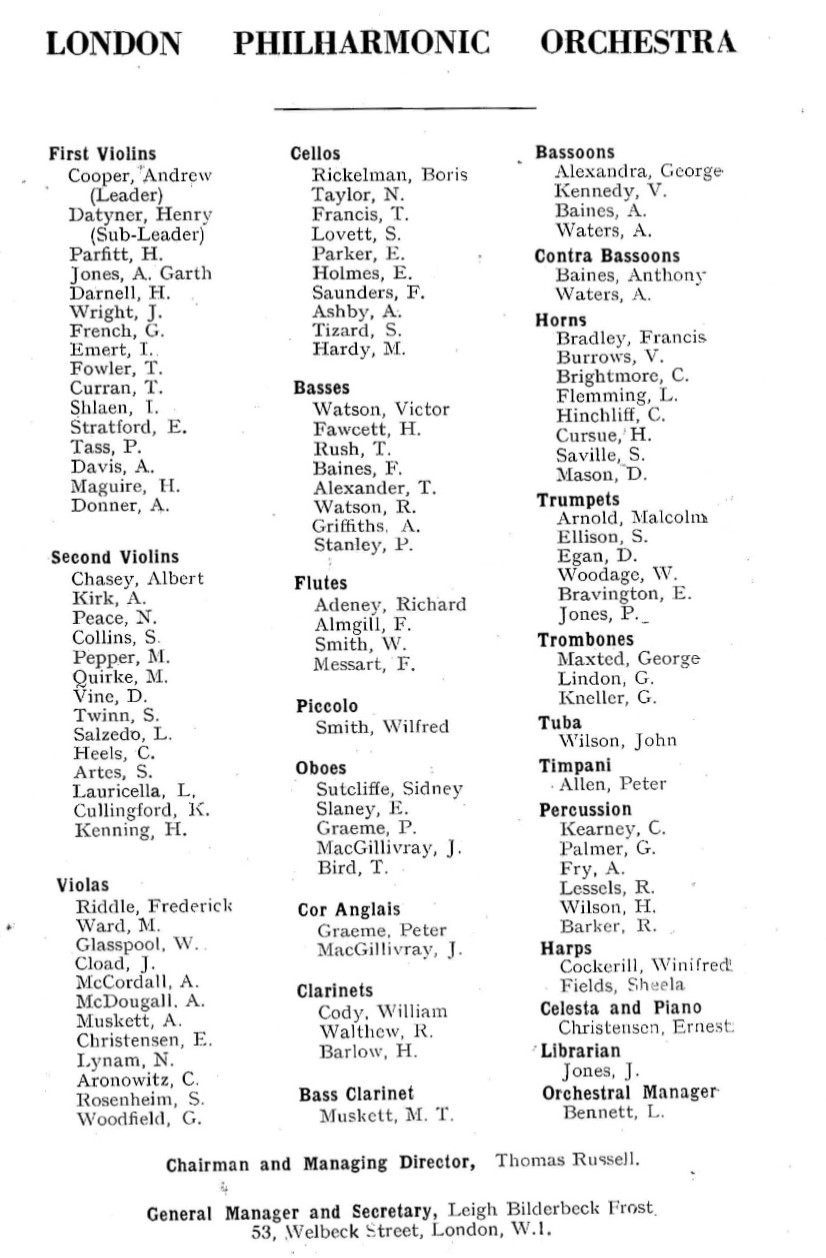

LPO Members – 1948

Between February 29 and March 25 1948, Furtwängler gave a series of ten concerts with the LPO, six in London and four on tour, with among others Brahms’ four symphonies on the program (the Second was played in London on March 11), and the last concert, on March 25, was devoted to Beethoven’s Ninth. Four days of recording were devoted to this Second symphony (March 20, 22, 24 and 25), and on March 26, Furtwängler recorded for EMI Brünnhilde’s Immolation with Kirsten Flagstad and the Philharmonia, before leaving for a series of concerts in Buenos Aires.

The reproduction of the sound of this recording of Brahms’ Second has always been problematic, for several reasons. John Culshaw tells us in his book ‘Putting the Record Straight’ that Furtwängler refused to use several microphones, so the recording was made with only one microphone, which was however a relatively common practice at the time. For example, DGG recorded Schumann’s Symphony no. 4 with Furtwängler and the BPO at the Jesus Christ Kirche in Berlin in 1953. However, Decca did not use this method and this may have created difficulties, as Decca’s recording of this Brahms symphony perhaps lacks a bit of presence, although when the 78s were released, EMG Letter praised the warmth of the sound in the excellent acoustic of Kingsway Hall. Added to this is the problem of the definition of the FFRR curve used by Decca for the LPs (LXT 2586 was released in June 1951), as the publisher used several versions of it in the early 1950s without the discs providing information on the exact version used.

The 1959 reissue in the ‘Ace of Clubs’ collection (ACL 50) allows to play this LP with the correct FFRR curve, to restore the recording with its original tonal balance. It should be noted that playing this record with the RIAA curve, which has become a standard since the 80’s, gives an unbalanced sound, and we lose a lot of the interpretation, especially with a lack of bass which severely affects the dynamics.

The sound recording is very musical, and reproduces the atmosphere of the Kingsway Hall. One can hear Furtwängler’s characteristic sound, as well as the fact that the orchestra does not have the depth of sound of the BPO or the WPO, which is not necessarily a drawback for this work.

9 réponses sur « Furtwängler – Brahms: Symphonie n°2 London Philharmonic Orchestra »

HD / Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZTOfhZxvWVHuL7k8JYfhUG254T78vy2I0k

Format CD / CD Quality (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZPOfhZdHlzaazNU14FVVO8VABmPpeUS0Nk

Apparently German sound engineers were much better 🙂 I wonder why Furtwängler refused to use several microphones… ? Anyway, thank You.

The technique of recording with one microphone was very common for mono recordings at the beginning of the 50s.

This was the case with Westminster and e.g. the Scherchen recordings in Vienna (Haydn symphonies etc.).

This was the same for Mercury, e.g. for the Kubelik Chicago recordings.

The last Toscanini NBC recordings in 1953 for RCA were also recorded with only one microphone (Mussorgsky Pictures at an Exhibition; Schubert Symphony n°9; and also Dvorak Symphony n°9 which you can hear on this blog from a tape).

As to the specific case of Furtwängler, this comes from Friedrich Schnapp, his favorite sound engineer, who used this technique for most of the wartime broadcasts with the BPO.

The problem with the Decca sound is that it was not very natural, and this was probably unacceptable for Furtwängler. Note that when he recorded the Franck symphony for Decca at the end of 1953, with still Victor Olof being the producer, there was no problem.

Great response! Thank You.

Thanks again for another great transfer and for your fascinating in-depth program notes!

Ron

Indeed, very interesting, thank you!

The list of LPO members is, alas, incomplete.

Among the doublebasses was my old, now late, friend Bob Meyer (1920-2016).

He told me about the first time Furtwängler walked into the rehearsal room: he was clearly a little nervous, as this was his first encounter with English musicians since the war.

As one man, the entire orchestra rose to their feet and applauded him.

With thanks for this very interesting comment.

The list of LPO members is taken from the program of the concert given in Watford on March 8, 1948:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/WF-LPO-Watford8March1948.pdf

This is probably the reason why it doesn’t list all the LPO members who performed with Furtwängler.

Your friend performed with Furtwângler not only with the LPO, but he also with the Philharmonia in Lucerne (1954):

https://robertmeyer.wordpress.com/2007/04/20/wilhem-furtwangler-conductor/

https://robertmeyer.wordpress.com/2008/04/20/professor-meyers-musings-on-beethovens-ninth-2-wilhelm-furtwangler/

Indeed.

Bob played under pretty much every major 20th century conductor, with the exception of Tosacanini.

When Toscanini visited London in 1952 and conducted the Brahms symphonies with the Philharmonia, Bob was not a regularly member of the orchestra (although he would join a few years later). He told me that he did not like the « fixer », i.e. the man who hired extra musicians for concerts, and so he did not want to ask to be hired.

He also told me he had always regretted it.