Étiquette : Artur Schnabel

Artur SCHNABEL – AUSTRALIAN TOUR 1939 PART I: Concerts n° 1 -11 (May 17 – June 13)

MELBOURNE, HOBART, SYDNEY, BRISBANE

Introduction: Der schwer gefaßte Entschluß… (The difficult decision)

Eighty-five years ago, Artur Schnabel toured Australia for three months (May 17 – August 16, 1939). His intention was to come back to Europe at the end of the tour, but it became more and more obvious in the course of time that Word War II was about to break out. Meanwhile, the tour went well and seemed undisturbed by the gruelling and heart-breaking decision he had to develop over time to leave all his belongings in Europe and go to the United States.

_________________________________

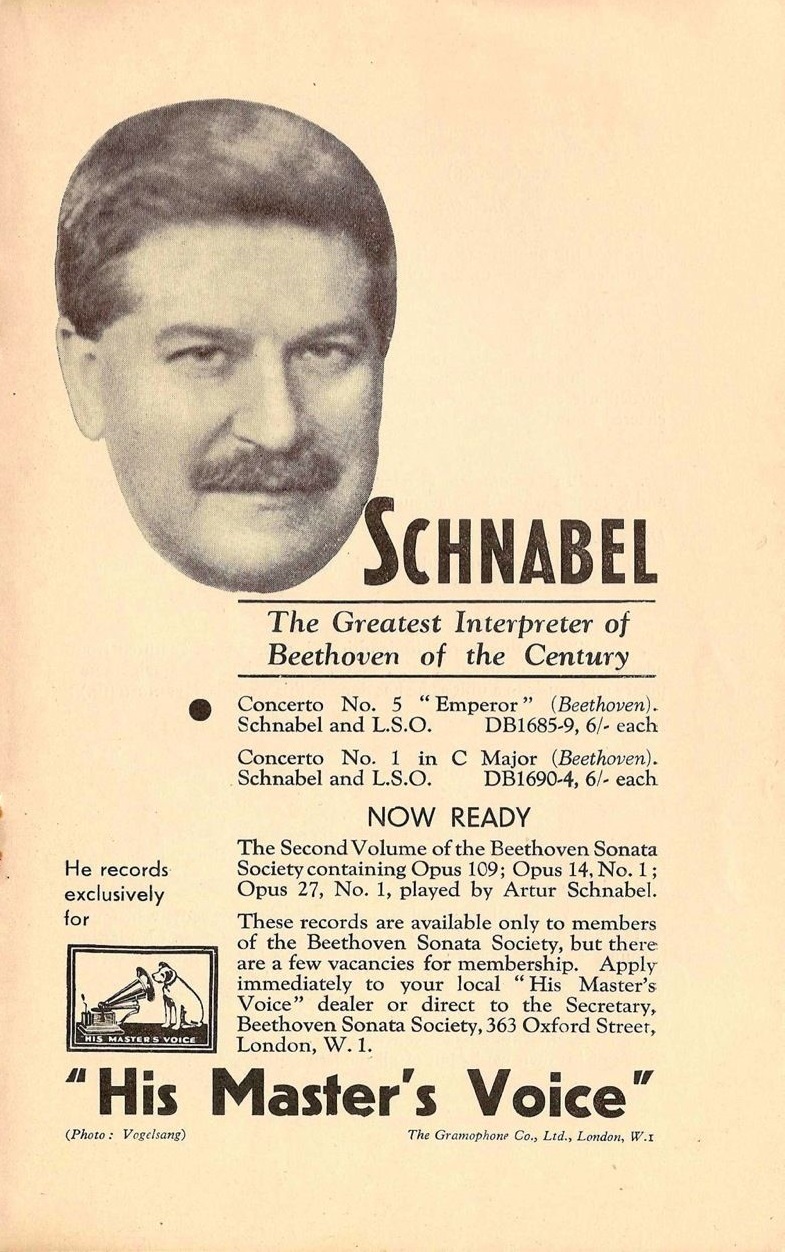

Between January 25 and 27, 1939, Schnabel made in London (Abbey Road Studio n°3) what were to be his last pre-war recordings. Thereafter, he travelled to the United States to give some concerts: Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago, San Francisco and finally Los Angeles, from where, on April 26, he took SS Mariposa to travel to Sydney where he arrived on May 15. The first concerts were in Melbourne and Hobart (Tasmania).

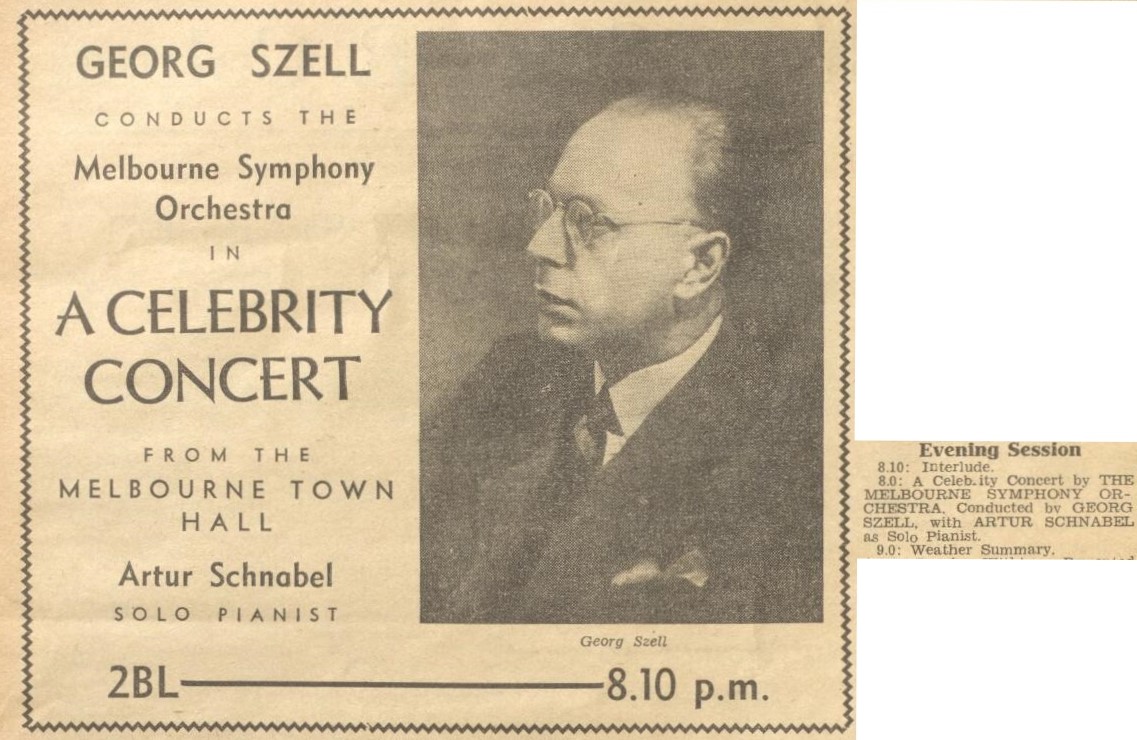

During this tour, Schnabel performed 5 different programs for his 16 piano recitals. There were also 2 chamber music concerts and 9 orchestral concerts, six of them being conducted by Georg Szell.

From Australia, he wrote letters to his friend Mary Foreman. They have been published in: ‘Artur Schnabel – Walking Freely on Firm Ground – Letters to Mary Virginia Foreman 1935 – 1951’ (Wolke Verlag). From them, we know the reasons why Schnabel took the very difficult decision of not going back to Europe and, at the end of the tour, of sailing to the United States.

01- May 17 MELBOURNE Town Hall

Melbourne SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEEETHOVEN Concerto n° 4 in G Op.58

Announcement of the broadcast of the Concerto by Beethoven

and below, rehearsal with Schnabel and Szell with the Melbourne SO

Argus (May 18): ‘A musical event of great importance, the first public appearance in Australia of Artur Schnabel, resulted in scenes of indescribable enthusiasm last night at the Town Hall. Music lovers rejoiced that for his opening concert in Australia, he paid the Melbourne Symphony players the supreme compliment of soliciting Beethoven’s G major concerto, a work which reveals his genius and his scholarship at their highest level of achievement. Professor Szell’s association with the great pianist gave further cause for congratulation. These two musicians have been partners in many a fine artistic enterprise, and each nuance and each hint of emotional significance in the Schnabel’s reading of the G major concerto is as familiar to the conductor. as to the soloist. There are some musical interpretations which defy analysis and remain in the memory as intangible but indestructible revelations of beauty. Of this rare calibre was the performance heard last night. No written summary could convey the poetry, the authority, the grandeur, and the impulsive youthfulness of an interpretation which, premeditated as to each detail of colour and form, avoided any suspicion of intellectual routine. Schnabel’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Beethoven’s compositions might easily tempt him to pedantic dryness. So alert and so eager are his mental reactions, however, that his renderings have the unspoilt freshness of improvisation. Although the Melbourne orchestra could not supply the beauty of tone necessary in the first movement of the concerto, the vivacity of rhythm in the finale and the admirable sense of mood achieved in the « andante » caused equal pride and satisfaction to all admirers of Australian talents’. Bicknell Allen

The Bulletin – Melbourne Chatter (May 24): ‘As their husbands are old friends, so are Madame Schnabel and Madame Szell, who where at the first row of the gallery with a bunch of A.B.C. (Australian Broadcasting Commission) people.

The Bulletin (May 24): ‘…The audience cheered, clapped and stamped when Schnabel played the G Major Concerto of Beethoven. Schnabel is one of the rare creatures who not only knows how to play their instruments, but how to play their audiences’.

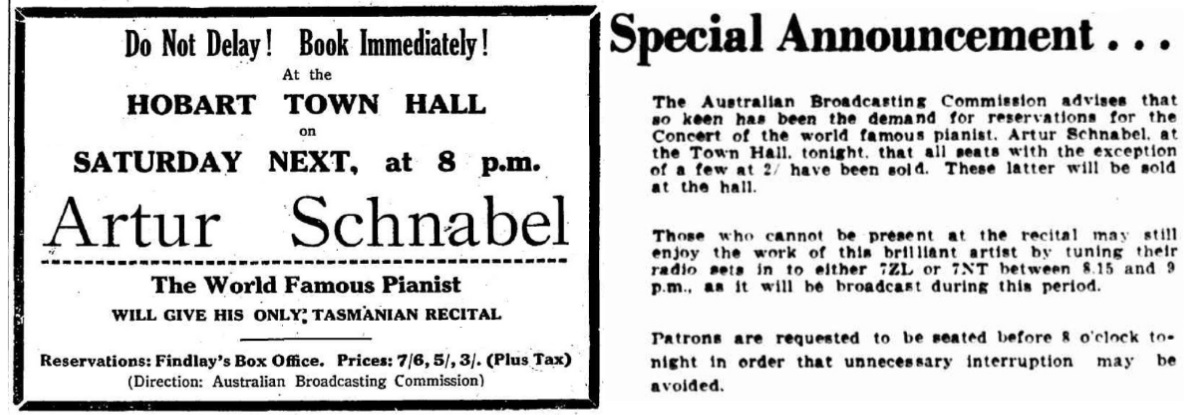

02- May 20 HOBART Town Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Mercury – Hobart: ‘Those who had the good fortune to be at Artur Schnabel’s recital at the Hobart Town Hall on Saturday night heard Beethoven played as they are not likely to hear lt for many years unless they hear Schnabel again. One can well believe, after having listened to his intensely authoritative readings of the A Flat and C Major sonatas that no other artist living can compare with Schnabel in his vast understanding of the piano works of the great composer. It was tremendous playing, and at the end, the large audience, which overflowed beyond the usual space of the hall – even onto the platform – broke into a storm of applause; a Schnabel audience, one imagines, is always enthusiastic. The pianist returned time after time to bow his acknowledgements, but there were no additions to the programme, for Schnabel does not give encores. « Applause, » he believes »is not an order, but a receipt. »…Schnabel’s absolute sincerity and rare penetration into the composer’s mind left, perhaps, the deepest impression. He never failed to get below the surface of the music and illuminate its essential characteristics. He absorbed himself and his art completely in his playing. The glorious A Flat Sonata, Op. 110, the second last which Beethoven wrote for the piano,,was a memorable experience. lt was a fluent exposition which left unexpressed none of the moving beauty and spirit of the music. Schnabel’s cantabile was delightful alike at the outset and in the statement of the fugue subjects. Clarity of tone, pursued so ardently, attained so rarely, was one of the secrets of this great performance. In Beethoven’s monumental « Waldstein » Sonata (C Major, Op.53) Schnabel, especially in the allegro con brio, rose to exceptional heights. His playing was unforgettable alike for meticulous and exquisite turn of phrase and for solidity and forthrightness. Great skill and expression were lavished on the allegretto. That Schnabel is not a Beethoven exponent alone was shown by his masterful interpretations of the Mozart A Minor Sonata and the four « Impromptus » which constitute Schubert’s Opus 142. The A Minor, typical of the emotional Mozart, alternately glowed and trembled with passionate beauty. The piano gave out a wealth of glorious tone, soaring at times to stirring climaxes, which, no matter how forceful, were always perfectly controlled. For me, the first and second of the « Impromptus » were the loveliest. Schubert’s enchanting’ melodies were articulated with complete lucidity, and the last two pieces were revelations of virtuosity. A Steinway plano was used hy Artur Schnabel at his recital. ’Themus’

03- May 25 MELBOURNE Town Hall

Melbourne SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEETHOVEN Concerto n°1 in C Op.15 – MOZART Concerto n°20 D Minor K466 – SCHUMANN Concerto in A Op.54

Australasian (June 3): ‘No more important musical event is likely to occur in Melbourne this year than the all-concerto concert given at the Town Hall on May 25 by Artur Schnabel and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. A profound musical scholar and the greatest contemporary exponent of Beethoven, Schnabel makes life difficult for orchestral associates unfamiliar with his analytical methods. The Melbourne Symphony players struggled pluckily to fulfil the insistent demands upon their technique and initiative, demands which were no more than commonplaces of interpretative routine to conductor and soloist, but which weighed heavily upon performers already sufficiently alarmed by Schnabel’s reputation and uncompromising devotion to « high-brow » principles. Artistic collaboration was out of the question, but, with the pianist as dictator and the conductor as a quick-witted and efficient intermediary, the orchestra provided an effective background for the magnificently handled solo passages. Beethoven, Mozart, and Schumann were the composers of Schnabel’s choice, and to each he devoted his great learning, his exemplary musicianship, and his consummate control of piano technique. As at the previous celebrity concert, when Schnabel gave an inspired performance of the Beethoven G major concerto, the Town Hall was « sold out » several hours before the programme commenced, and voices, feet, and hands swelled the torrents of applause. To watch the face of Artur Schnabel when he plays the andante section of the G major concerto would bring a deaf man into spiritual communion with the music’. ‘Musician’

The Herald (May 26): ‘Schnabel’s masterly playing of the Schumann A Minor concerto made an exhilarating climax to the concert in which the eminent pianist was associated with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, under Professor Georg Szell’s direction, in the Town Hall last night. Breadth and strength characterised the playing of the artist, who, in the performance of three concertos, again impressed as both a great pianist and a profound musical scholar. Never did Schnabel’s playing flag and never was there anything superficial in the playing. His interpretations were intensely alive, piercing to the core of the music. While he gave luminous readings of the Beethoven No. 1 and Mozart’s D Minor (K466), the peak of achievement was reached in the Schumann, because the pianist had better support from the orchestra, which was responsive to every mood of Schumann. The orchestral background seemed to be revitalised on this occasion. Although strong and exhilarating, the performance did not lack tenderness. It was at once distinguished by the vitality, clarity, and romantic spirit with which soloist and orchestra developed the web of harmonies of the first movement, In the Intermezzo the audience was enchanted with the gracious charm of the interchange of themes between the piano and strings, and later the woodwind. Sensitive cello tone came in the sustained melody against the arpeggio passages of the piano. A magical effect was achieved just before pianist and orchestra entered into the brilliant and joyous Allegro Vivace. Schnabel and the orchestra revelled in the animated first part of this movement, with the arabesques of the piano dancing round the sprightly melody voiced by various parts of the orchestra in turn. The pianist made a sterling impression by his brilliancy as he proceeded from one tour de force to another to the exciting close. The drama of Mozart’s D Minor concerto made a deep impression. In the first movement there was a cadenza of arresting interest. This was a real dramatic summing-up, that tightened not loosened, the interest. The concert was begun with the Beethoven work, which was most notable for the spontaneity of the Rondo. Schnabel had better support later in the night than he received in the earlier movements. J. E. Tremearne

On May 26, Artur Schnabel and his wife Therese Behr flew to Sydney. Schnabel was to give four recitals in a row. The picture below shows them at their arrival in Sydney.

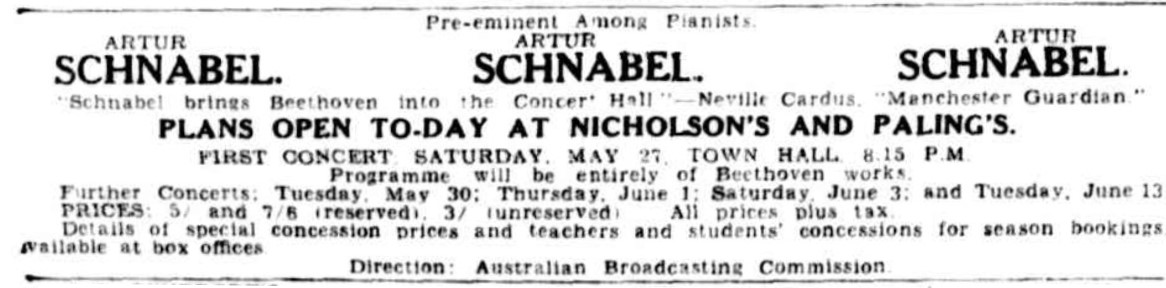

Announcement for the Sydney Recitals

04- May 27 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 1

Original Program [BEETHOVEN Sonatas n°2 Op.2 n°2; n°31 Op.110; n°17 Op.31 n°2; n°21 Op.53]

Announcement (May 15) for the May 27 Recital

The amended program, no longer with only Beethoven Sonatas, was announced in the press on May 20, the day of the Hobart Recital where the same program (‘Program 1’) was played:

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Daily Telegraph (May 29): ‘Artur Schnabel, opened his Sydney season with an electrifying concert at the Town Hall on Saturday night. Schnabel, a small man, discarded the usual pianist’s stool for a high-backed chair, against which, in slow movements, he would lean back listening intently to the lovely sounds he, produced. He demanded the undivided attention of the large audience. Schnabel’s reading of Beethoven’s Sonata in A Flat Major Opus 110, was so fresh and spontaneous that the work, heard dozens of times before, seemed to have been written only last week. Unbelievably delicate gradations of tone and color added detailed loveliness to the great architectural interpretation. There was no exaggeration; each note received just the right value to balance it with the rest of the work. Technical difficulties seemed not to exist. Yet there was nothing of the self-advertising virtuoso about the performance. One felt that the credit was due primarily to the composer, rather than to the player. This was no so with Schubert’s Four Impromptus. In this group one felt « Here is great playing, » not « Here is great music. » And it was only the combination of Schnabel’s immense personality and faultless playing that sustained the interest throughout the over-long work. The first movement of Mozart’s A Minor Sonata (K.310) lacked the delicately smooth yet firm articulation which characterises ideal performances of that master’s work. But Schnabel played the rest of the sonata with transcendent beauty of phrasing and tone. He concluded his generously long programme with a monumental performance of Beethoven’s « Waldstein » Sonata, which left the audience in a state of high elation. To call Schnabel’s performance of this work « poetic » would be to use a word staled by hackneyed use to describe a thing of new-born freshness. Yet poetry, true poetry, was in every note. An unforgettable and beautiful experience’.

Sun (May 29): ‘There is some piano playing so superb that one can only lose oneself in admiration for it. The combination of intellectual and emotional understanding of music, and of transcendent technique is so rare that such an experience is not often enjoyed in the concert hall. Artur Schnabel, however, gave lovers of music this supreme gift at his first recital in Sydney Town Hall on Saturday night. We have heard some technicians as fine, and a few pianists who were able to reach beyond the technical mastery, and the mechanism of strings and keys to the spirit of the music behind and above these things,but it is difficult to remember a player who can satisfy as Schnabel can. His most obvious quality is that of reserve. He greets his audience quietly, and then, sitting at the piano, promptly forgets it – except when some loud cough breaks in upon him, when he frowns and shakes his head as he seeks to recapture his mood. He has no distracting mannerisms. He opened his concert with the Sonata Opus 110, a late work of Beethoven not often heard on the concert platform, and containing much of that metaphysic which makes the later Beethoven so difficult to interpret. No such interpretation as Schnabel’s has been heard in Sydney. He resolves the difficulties of phrasing and of thought as if Beethoven himself were speaking, still retaining that sense of the mystic, which is the ultimate wonder of all great music. The « Waldstein » Sonata is usually regarded as a virtuoso piece, something written for technicians, and we have heard many performances which give color to that idea. The « Waldstein » Sonata, as it was done by this fine musician, was an utterance of music just as moving and as beautiful as any piano work ever written by the Master. The Mozart Sonata in A Minor has been done by almost every advanced piano student, and never by a professional pianist from abroad until it was done at this concert. The pianist brought out into relief the escape from formalism of the growing musical individuality of Mozart. Mozart is so often played four-square with an attempt to give meaning to him by a certain fragility. As Schnabel sees him, he is a man’s composer, with a virile musical message. The four Impromptus of Schubert were played together, as impressive as a sonata in a sort of contrasting unity of sense, if not of form. Listening to this great pianist and musician, one wondered why other virtuosi have not sought further into the essential Schubert. The reaction of all this beautiful music on the audience was obviously great. With the exception of one or two stentorian coughs, even those with irritable throats bottled up their coughing to let it go between sonata movements. During the actual playing not a sound was heard from that crowded house. The applause was continuous. The pianist was recalled again and again, though it was known that he would play no encores. He says that he has found Australian audiences understanding and sensitive, and Saturday night’s audience plainly manifested these qualities’. H.A.

Publicity for Bechstein Pianos (May 28)

In Hobart however (May 20), he played on a Steinway piano, but for the whole Tour, Bechstein was of course the instrument of his choice.

05- May 30 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Sydney Morning Herald (May 31): ‘Artur Schnabel once again made a profound impression last night when he gave his second recital at the Town Hall. The cordiality of the applause at the end indicated how deeply the audience had been stirred even though there was no attempt to transgress the pianist’s wishes and demand encores. The Schubert sonata was especiallv interesting, for the new light it threw on this composer. Until recently Schubert’s accomplishments in sonata form where overshadowed by his fame as a svmphonist and a song writer, and by the popularity of the Impromptus. But abroad during the past few years, Schubert’s sonatas have been reinstated as first class music. And Schnabel himself has been a leader in that movement. The B Flat Sonata was remarkable for its extreme lyric beauty and for its graceful simplicity of form. It glowed and beamed under the pianist’s melodic eloquence. Everything seemed easily done, yet the details had that exquisite proportion which only the greatest concentration could bring to pass. The climaxes grew so surely and so spontaneously that they seemed an organic development rather than a series of consciously thoughtout effects. A similar selfless devotion to the musical thought appeared in the C Minor Beethoven. Schnabel last night gave it a new intensity, a new sparkle, an entirely unexpected set of values It was all done by simplification and not by the imposition of an arresting and picturesque personality. Therefore, it seemed irresistible and noble. The Mozart also was playing of a richly aristocratic quality. It had strength and resonance yet every phrase had been polished to the last degree. The crown of the evening’s music, however, was the Beethoven Opus 109. To this strange and powerful product of the composer’s later years, Schnabel brought a corresponding maturity. The great range of the tonal effects , the clouded qualitv of the song, the abrupt shifting of mood, the brooding and the interludes of radiant calm – all these found expression on the grandest scale’.

Sun (May 31): ‘Schnabel’s selection from Schubert was the Sonata in B Flat, a long work with a very diffuse first movement, which, had it not been for Schnabel’s rare gift of making poetry out of blemishes, might have proved dull. The second and third movements were pure Schubert, down to the finest detail. One feature of Schnabel’s technique which deserves particular attention is the sonority of his bass, the harmonies of which, in some of the Beethoven movements, assume a truly symphonic volume. The prestissimo section and the more richly harmonised portions of the final variations in the great Beethoven work In E Major Op.109 were handled by this pianist with studied attention to harmonic embroidery. Schnabel’s choice from the Mozart album was an exquisite and melodious Sonata in F Major, practically unknown to concertgoers here. Instead of the broad, powerful imaginative flourishes given to his Mozart playing on Saturday night, the treatment was more delicate. The audience greeted an old friend in Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata, which was done with verve and breadth of conception. Repeated calls for an encore at the conclusion of the concert were met with polite bows from Schnabel, but there was no more music’.

06- June 1 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 3

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°3 in C Op.2 n°3 – Sonata n° 17 in D minor Op.31 n°2

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.90 D899 – SCHUBERT Sonata n°17 D Major Op.53 D850

Daily Telegraph (June 2): ‘His first offering was Op.2 n°3 in C Major, » a work known to every young piano student. In this, which he started rather restlessly, Schnabel used more pedal than usual – much more, in fact, that he advocates in his own edition of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. His slow movement, especially the bit with crossed hands, was a marvel of lyrical beauty. The fortissimo passages, when they came, made a tremendous effect. There was no attempt to make the minuet dainty. It just bubbled with masculine good humor. Even In the most delicate passages of the last movement, Schnabel never for a moment lost his intense virility. The other Beethoven work was the Sonata in D. Op. 31, No. 2. Schnabel illuminated this work, too, with that insight into its essential meaning, through which he makes the most complex music seem easy to his audience. His was the only way to play the work. You knew that at once, despite an occasional blurred articulation. Schubert’s Four Impromptus, Op.90 and Sonata in D Major, Op. 53, took up the rest of the programme. Beautifully though they were played, Schubert makes a poor show after Beethoven’. J.R.

Sun (June 2): ‘Of the works on the program, the Beethoven in D Minor was naturally the most impressive. The pianist found here material for one of those splendid interpretations which distinguish him, its strongly organised structure and dramatic power being realised magnificently. Particularly beautiful was the treatment of the slow movement, in which the handling of the chords, so accurately and yet so gently played, was a notable feature. In his chord playing, one always notes with Schnabel an extraordinary dynamic control, resulting in the most lovely shading of such passages,and a significance in phrasing which lesser players miss. It is more than technique – any good technician could do it – but few of them have the instinct to do it. Such passages, for instance, as the opening of the slow movement in the C Major, revealed on examination some very subtle differences in volume and color of a series of chords which seemed, on considering the whole, evenly played. These variations gave life to the phrases which a less subtle treatment denies them. Schnabel, with all his technical accomplishment, is not superior in this respect, to many other pianists we have heard. Listening to the D Minor Beethoven last night, however, it was possible to see that the secret of his pre-eminence in interpretation of the classics is an almost unique capacity to see a movement as an organic whole, and to keep it always within the frame. An approach reserved, and at the same time warm, enables him to give the full poetic significance to these works, which are, after all, poems in sound. Again he demonstrated his power of holding his audience, not by platform tricks, not by any attempt at ingratiation, but by the sheer force and understanding of the music he plays, an understanding which he communicates to those who hear him. Even the Schubert Sonata, inorganic as it was, lacking development,and relying superficially on its melodic interest, he invested with a certain glow, for the time making one feel that, instead of a good work, it was a great one. That capacity to give quality to a work which somewhat lacks it, is the finest and rarest mark of a great player’. H.A.

07- June 3 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 4

BACH Toccata C Minor BWV 911 & D Major BWV 912 – SCHUBERT Moments Musicaux Op.94 D780

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°25 Op.79 – Sonata n°24 Op.78 – Sonata n°32 Op.111

Sydney Morning Herald (June 5): ‘One could have foretold from knowledge of his earlier performances, what style the pianist would bring to Bach’s music. Yet, the reality, when it came, was surprising in the degree of its breadth and penetration. This was Bach reduced to the simplest terms, square and powerful, yet not in the slightest dessicated. During his four Sydney concerts, Schnabel presented Beethoven on a new scale, with a new set of values. When displayed by the majority of pianists, a Sonata like the G Major Op.79 sounds a trifle thin and dated. One has been aware, at times,that this sonata fails to equate others and later works in the exploitation of technical possibilities,and of the full sonority of the keyboard. Yet, with Schnabel as interpreter, nothing of that impression remained. The three movements sang fully and completely, and the music was re-established. The G Major sonata was followed by the one in F sharp Op.78. This was irresistible in its suave grace. Finally, Schnabel played the towering Op.111. In sheer sultry majesty and introspective passion, the first movement stood supreme. The stormy, rumbling declamation of the bass was uncompromising, abrupt, minatory. It had an elemental roll, a colossal sweep of colour. The remaining work was the Op.94 of Schubert. Even Saturday night’s playing, exalted as it was, could not give these miniatures any particular importance. That was probably not the player’s aim. What he did do was to point out Schubert’s lucidity and fragikity and perfect taste when it came to a series of charming trifles’.

Daily Telegraph (June 5): ‘The Town Hall was filled on Saturday night for the last concert of Artur Schnabel’s present season. Once again he demonstrated his complete mastery of Beethoven’s works. The performance of the evening was the Sonata in C Minor, Op.111. He handled this monstrously difficult work without apparent effort. Under his fingers, the lovely Arietta sang its way upwards until it dissolved into the most ethereal sounds I have ever heard come from a pianoforte. Fortunately the Op.111 was the last item on the programme. It would have been impossible to listen to anything else. But Schnabel had already given inspired performances of the slight Op.79 and the more profound Op.78. There was no nonsense about Schnabel’s playing of the two Bach Toccatas in C Minor and D Minor, with which he opened the concert. The several parts in the complicated polyphonic writing could all be heard with beautiful clarity. Once again Schubert figured prominently on the programme, this time with the Six Moments Musicaux. Schnabel lent these more or less trivial pieces a vicarious dignity. But many of them, particularly the Andantino, are too long. If they represented what Schubert took to be a « moment, » he must have suffered from some strange aberration of the time sense’ J.R.

The Bulletin – Melbourne Chatter (June 7): ‘On Saturday night, he had an inauspicious beginning. His first item was a Bach toccata. He was just getting into its stride when there came a fizz and a flash as of lightning. A photographer leaning over the balcony had done the fell deed. Schnabel, rudely awakened, played on for a few bars, then stopped abruptly, muttered several fierce denunciations in a foreign langage, and when a little calmer, started all over again.’

08- June 6 BRISBANE City Hall

Brisbane SO dir: Percy CODE

MOZART Concerto n¨23 A Major K488

On June 6, the Brisbane newspaper Telegraph published an article ‘Walking and Talking with Schnabel’, which relates the conversation between the pianist and the newspaper’s music critc walking together from Schnabel’s hotel to the rehearsal room for the 11 a.m. rehearsal at City Hall with the orchestra. To read the article, click HERE

Telegraph (June 7): ‘Artur Schnabel amazed his audience at the City Hail last night by his own unobtrusiveness. He played the solo part in Mozart’s A Major Concerto as if he were the least important of all the musicians on the platform. He sat at the piano and played as if he were merely gratifying a whim of a few friends at his own fireside, often keeping both eyes on the conductor and none on the keyboard. Twice in the last movement, his hands actually rose higher than the top of the grand piano, and there was not a movement of any kind in his bodily position. He gave us the best Mozart playing we have ever had. His clear rippling tone was admirably balanced with the orchestra, every tiny figure of ornamentation which Mozart wrote was there in its proper place, beautifully clear. He seemed to have unlimited reserves of power. In the slow movement, his tone was gloriously pure. I do not think we have ever had a concerto performance in which there has been the same degree of close collaboration between soloist and orchestra. Mr. Percy Code managed the orchestra very successfully, holding it down to just the right strength of tone on nearly every occasion, and it was not his fault that here and there tiny blemishes appeared in the wood-wind performance’. A.H.T.

09- June 8 BRISBANE City Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Telegraph (June 9): ‘The unobtrusiveness that was noted in the earlier Mozart concerto performance was not abandoned. Schnabel allows nothing to come between him and the music. One soon took his technical powers for granted. For no technical hurdles seemed to matter. The intense spirituality of the sonata Op.110 seemed to grip him as it did every member of the audience. The marvel is how he achieves such variety in tone colour, and in the actual weight of tone, without obvious effort. His fortes rise like an incense from the keyboard. Every phrase and every nuance is so carefully conceived and executed, and yet seems to be so part and parcel of the man himself, that it completely disarms criticism. There is no fuss or bother even about his big tone, which seems to come unbidden, from a slightly raised elbow and wrist. For sheer control of tone the series of chords rising from pianissimo to fortissimo in the last movement of the Op.110 were perhaps the most surprising. He made every one of those chords a very great surprise, and one began to wonder how much longer he could have gone on increasing the strength. The crystal purity of his tone made it carry to every part of the hall and he seemed to annihilate distance with it, his softest pianissimo being as audible from the gallery as his loudest tones. It was an unforgettable experience. The four Schubert Impromptus Op.142 were so perfectly matched as to almost form a sonata, though rather a long one. Schnabel believes that Schubert is a much underrated pianoforte composer to-day. He proved it in this performance, which had all the clarity, all the melodic richness of content, and all the fire one could wish for. Professor Donald Tovey has remarked that it was time we ceased regarding Mozart as a namby-pamby, and « lavender and old lace » composer and gave him something of the bigness that is his due. That is precisely what the pianist did last nightwith his A Minor Sonata K310. Its dynamics were, in Mr, Schnabel’s hands, very much the same as the Schubert and the Beethoven. The Beethoven « Waldstein » sonata has never been heard here before as it was heard last night. The performance was magnificent. Great as the playing had been earlier, I do not think there was anything quite like the marvellous variety in colouring that he gave the last movement, nor anything to match the crystal purity of his tone in the slow movement. It was sheer keyboard wizardry with the wizard performing with the nonchalance of a conjuror producing rabbits from a hat’.

10- June 10 BRISBANE City Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Telegraph (June 12): ‘Rarely or never have we been visited by a player who could take so much for granted on the merely technical side and who was in consequence so free as he to devote himself to what one cannot but call the spiritual content of the music. Lesser men watch their keyboard as though it otherwise might play them some trick. He had other things to watch. The result was, for example, a new and utterly transformed « Pathetique », that Beethoven Sonata heard so often as to provide the test almost of the hackneyed, and a Mozart which in hands less great would sink to tinkling prettiness, but which in his was a thing of unblemished grace and graciousness. One might discourse on the detail of this perfectly architectured programme, on the glorious statement of the recurring theme in the first movement of the Schubert Sonata, on the etched rhythm of its Scherzo, on the dynamics of the first movement of the final Beethoven and so on, were it not an impertinence to do so. There must have been many in that audience who, like the writer, had heard recorded versions of Schnabel’s work years ago, and said: « This is the greatest of the pianists, but, of course, I shall never hear him. And now, the incredible has come to pass’. H.W.D.

11- June 13 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 5

SCHUBERT Sonata n°20 in A Major D959 – WEBER Sonata n°2 A Flat Op.39 –

SCHUMANN Davidsbündlertänze Op.6

Sydney Morning Herald (June 14): ‘The program was lighter in calibre than any that had gone before, but nonetheless satisfactory. The Weber Sonata in A Flat Op.39 provided an especially interesting experience. A deep and bodyful work of art, it was obviously not. Yet Schnabel made it endlessly endearing. He made everybody see clearly that, although Weber was to some extend preoccupied with pianistic devices, the means rather than the intellectual end, he accomplished his aim with unfailing taste and true musical feeling. The caressing delicacy of melody, the enormous sweep and colour of the sonorities, which made the Weber so joyous has been exemplified earlier in equal measure in Schubert posthumous A Major sonata. How gently, almost casually, the player stated the opening theme! One was hardly aware that he had begun to play so lightly, so meditatively, did the tiny tune express itself. The second movement was memorable in its concentrated simplicity diversified in sudden blazes of temperament. The interpretation of the Schumann was more steadily open to question than anything Schnabel had done during this season. Parts of this fragmentary series had an ineffable lightness, a caprice and fancy that were completely persuasive. Yet at other times , an air of serious introspection seemed to mist over the true waywardness of Schumann’s thought. Still, the general effect of the ‘David Society’ dances was supremely brought. It was an inspiring conclusion to the recital.

Letter to Mary Foreman (June 15): ‘I have now, the first time in Australia, four concert- and journey-free days, the heaviest work is done with a fairly average accomplishment, Eleven appearances, five recitals in Sydney, twenty-five big works performed, many of them for the first time here; now many repetitions will come, but still seven to ten pieces not yet played. In a way, I feel bored by the idea of repeating items; to play another program at each concert is much more attractive, but there is of course a limit’.

With this one-week pause, the next concert took place in Adelaide, on June 20.

_________________________________

They had six concerts together, so Schnabel and Szell had ample time to meet and socialize!

_________________________________

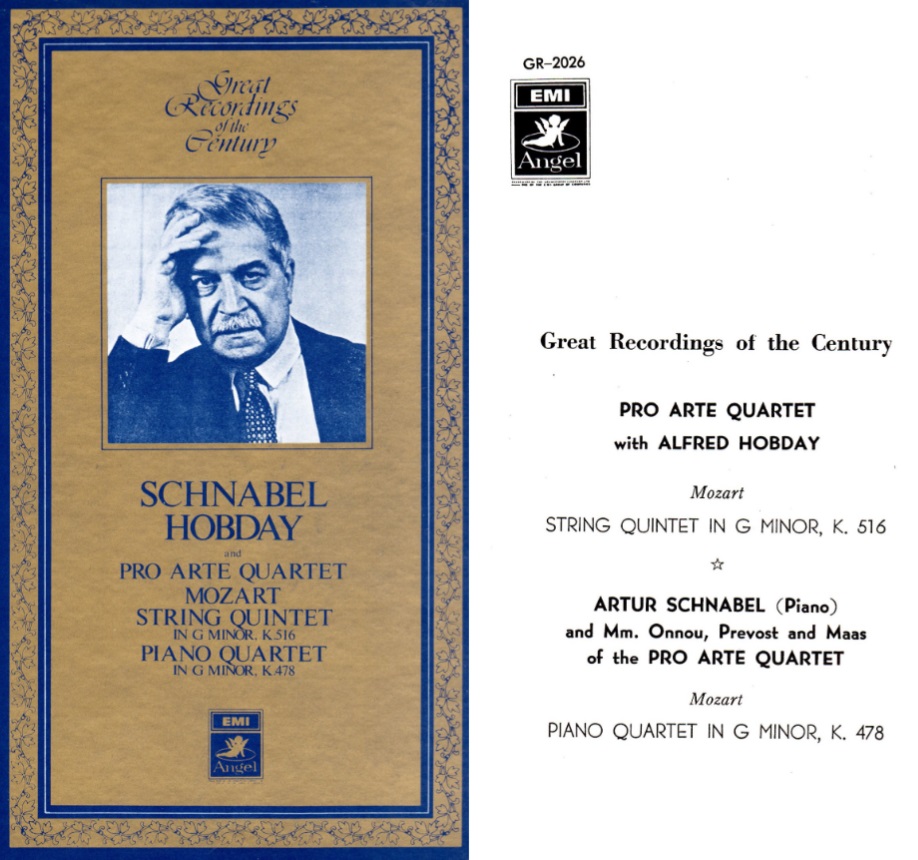

Mozart Quintet K.516

Quatuor Pro Arte

(Alphonse Onnou & Laurent Halleux, violon, Germain Prévost, alto, Robert Maas, violoncelle); Alfred Hobday, alto II

Abbey Road Studio n°3 – 15 February 1934

____________

Mozart Quartet K.478

Artur Schnabel, piano; Membres du Quatuor Pro Arte (Alphonse Onnoux, violon, Germain Prévost, alto, Robert Maas, violoncelle)

Abbey Road Studio n°3 – 31 January 1934

Source: 33t/LP Toshiba-EMI Angel Japan GR-2026

Voici deux enregistrements mozartiens du Quatuor Pro Arte, à savoir le chef d’œuvre absolu que constitue le Quintette en sol mineur K.516, couplé au Quatuor avec piano K.478, également en sol mineur, avec Artur Schnabel.

Pour le disque GR-2026 qui fait partie d’une série de rééditions japonaises en microsillons réalisée avec le plus grand soin à partir des matrices métalliques d’origine, il y a étonnamment peu de bruits de surface (sauf au début du Quatuor K.478).

Pour le Quintette K.516, la partie de deuxième alto est tenue par Alfred Hobday (1870-1942) qui a été le partenaire du Quatuor Pro Arte pour leurs enregistrements de Quintettes et de Sextuors (Mozart Quintettes K.515, K.516 et K.596, Brahms Sextuor n°1 Op.18), mais également du Budapest Quartet (Brahms Quintette n°1 Op.88 et Sextuor n°2 Op.36). Les faces enregistrées le 14 février 1934 (matrices 2B 6023-6029) ont toutes été rejetées et détruites, et le Quatuor a de nouveau enregistré le Quintette le lendemain (matrices 2B 6030-6037).

Here are two Mozart recordings by the Quatuor Pro Arte, namely the absolute masterpiece that is the Quintet in G minor K.516, coupled with the Piano Quartet K.478, also in G minor, with Artur Schnabel.

On the GR-2026 disc, one of a series of Japanese LP reissues made with great care from the original metal parts, there is surprisingly little surface noise (except at the beginning of the Quartet K.478).

In the Quintet K.516, the part of second viola is played by Alfred Hobday (1870-1942), who was the partner of the Pro Arte Quartet for their recordings of Quintets and Sextets (Mozart Quintets K.515, K.516 and K.596, Brahms Sextuor n°1 Op.18), but also of the Budapest Quartet (Brahms Quintet No.1 Op.88 and Sextet No.2 Op.36). The sides recorded on 14 February 1934 (matrices 2B 6023-6029) were all rejected and destroyed, and the Quartet recorded the Quintet again the following day (matrices 2B 6030-6037).

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

Artur Schnabel, piano

Quintette Op.44 Quatuor Pro Arte

Abbey Road Studio n°3 – 19 November 1934

Source: 33t/LP Toshiba-EMI Angel Japan GR-2169

Concerto Op.54 Alfred Wallenstein Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra (LAPO)

Glendale (CA) – Hoover High School 4 March 1945

Source: 33t./LP Bruno Walter Society BWS-724 – annonce/announcement: fichier mp3/mp3 file (Internet)

Artur Schnabel a peu enregistré Schumann pour le disque, uniquement ce Quintette et les Kinderszenen. On a deux enregistrements publics du Concerto pour piano, l’un avec le NYPO et Pierre Monteux, et l’autre avec le LAPO et Alfred Wallenstein. Au programme de ses récitals, on trouve rarement des œuvres de Schumann (Davidsbündlertänze Op.6 et Fantaisie Op.17).

En 1975, lorsque BWS a publié en microsillon l’enregistrement du Concerto avec Alfred Wallenstein, Karl-Ulrich, le fils du pianiste, l’a écarté comme étant un faux. Pourtant, l’enregistrement du concert complet existe avec les annonces radio (il est disponible en mp3 sur Internet), et Schnabel en relate les conditions très particulières dans une lettre datée du 5 mars 1945 à son amie et confidente Mary Virginia Foreman:

‘ Hier soir, c’était le premier concert à Glendale. C’était la ‘Standard Oil West Coast hour’. Ils m’ont trompé en ne me le disant pas, et j’ai joué pour le même cachet que pour les autres concerts, où personne sauf les gens présents dans la salle peuvent entendre l’exécution. Je suis heureusement assez vieux pour ne pas faire d’histoires ou me mettre en colère. Le concert – si on peut le dénommer ainsi – n’avait aucun sens. Répétition à 16h30. J’ai donc joué le Schumann trois fois en l’espace de quatre heures. La ‘Standard Hour’ se doit de bourrer soixante minutes avec de la musique. Elle l’a fait avec: Ouverture d’Hansel and Gretel, Air du Concours de Wagner (sans chanteur), le Concerto de Schumann, et l’Apprenti de Dukas – et quelques mots pour les retardataires. La salle, une grange hyper-résonnante.’

Si le jeu de Schnabel est ici inhabituel au point d’avoir dérouté son propre fils, ceci semble dû au peu de temps de répétition qui a empêché une coordination entre les deux musiciens et à la direction un peu rude et peu différenciée de Wallenstein, qui a cependant l’avantage d’imprimer une tension permanente (ou si on veut, une ’fièvre schumanienne’) au discours musical, qui semble manquer parfois à la version plus orthodoxe avec Pierre Monteux*. Autrement dit, Schnabel est ici sous pression.

L’enregistrement du Quintette Op.44 possède toute la tension nécessaire, mais Schnabel joue avec ses partenaires habituels du Quatuor Pro Arte.

* Concert donné une seule fois à Carnegie Hall avec le NYPO le 13 juin 1943 (au lieu du 27 juin), avec une seule répétition le 12, donc des conditions à peine meilleures qu’en Californie 2 ans plus tard.

Artur Schnabel has made only two commercial recordings of the music by Schumann, only this Piano Quintet and the Kinderszenen. We have two live recordings of the Piano Concerto, one with the NYPO and Pierre Monteux, and one with the LAPO and Alfred Wallenstein. In his recitals, he rarely performed works by Schumann (Davidsbündlertänze Op.6 et Fantaisie Op.17).

In 1975, when BWS isued the LP with the recording of the Concerto with Alfred Wallenstein, the pianist’s son Karl-Ulrich dismissed it as a counterfeit. However, a complete recording of the concert exists with the radio announcements (it is available as a mp3 on the Internet), and Schnabel describes the very peculiar conditions in a letter dated Mars 5, 1945 to his friend and confidante Mary Virginia Foreman:

‘ Last night was the first concert in Glendale. It was the Standard Oil West Coast hour. They cheated me by not telling me this, and I played for the same fee as for the other concerts, when nobody except the people in the hall can hear the performance. I am, fortunately, now old enough not to get fussy or angry. The concert – if one could call it that – was just barbarous. Rehearsal at 4.30pm. I accordingly played tne Schumann three times within four hours. The Standard Hour has to stuff sixty minutes with music. It did with: Hansel and Gretel Overture, Prize Song by Wagner (no singer), Schumann Concerto, Dukas’ Apprentice – and words for latecomers. The place, an over-resonant barn.’

If Schnabel’s playing is here unusual to the point of having puzzled his own son, it seems to be due to the lack of rehearsal time which did not allow a coordination between the two musicians and to the rather hard and undifferenciated rendering of the score by Wallenstein, which however has the advantage of bringing a permanent tension (or ‘Schumann fever’ if you will) to the musical discourse, which seems to be lacking at times in the more conventional performance with Pierre Monteux*. In other words, Schnabel plays under pressure.

The recording of the Quintette Op.44 has all the required tension, but Schnabel plays with his longtime partners of the Quatuor Pro Arte.

* Concert given only once at Carnegie Hall with the NYPO on June 13, 1943 (instead of June 27), with a single rehearsal on June 12, thus hardly better conditions than in California 2 years later.

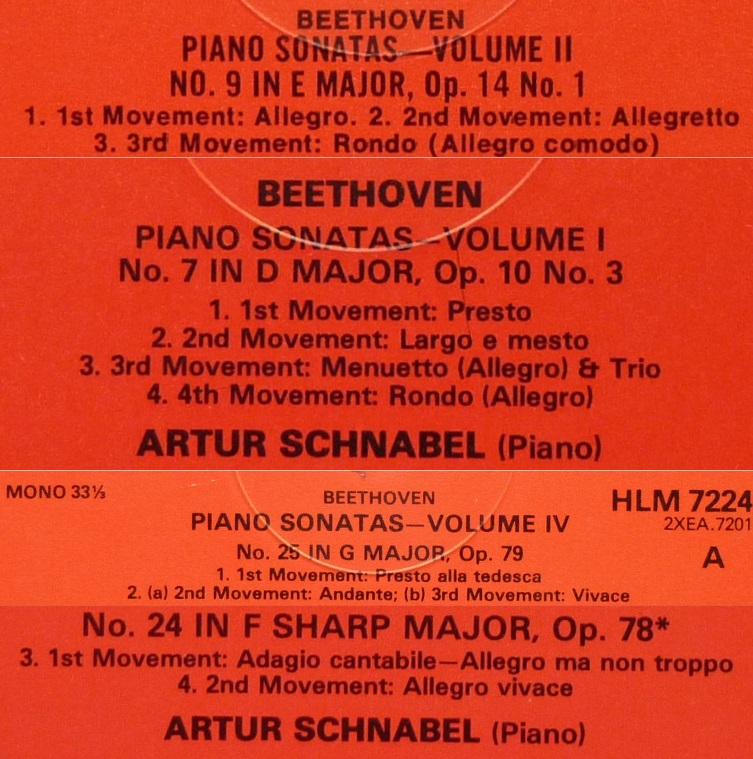

Sonate n°9 Op.14 n°1: 25 Mars 1932

Sonate n°7 Op.10 n°3: 12 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°25 Op.79: 15 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°24 Op.78: 21 Mars 1932

Sonate n°32 Op.111: 21 Janvier, 21 & 22 Mars, 7 Mai 1932

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le septième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comprenait les cinq sonates ci-dessus, les deux premières étant, comme pour les autres récitals, jouées avant l’entracte.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le septième récital, donné le 26 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, a eu lieu au moment où, autre événement de la saison new-yorkaise, Arturo Toscanini poursuivait avec Rudolf Serkin la série de ses concerts d’adieu en tant que chef titulaire du New York Philharmonic. L’interprétation par Schnabel de la sonate n°24 Op.78, dédiée à Therese von Brunswick, a atteint un niveau tel qu’elle a presque ‘ volé la vedette’ à l’Opus 111! (voir la critique ci-dessous). Une idée de génie de la part de Schnabel que d’associer ces deux œuvres pour terminer son intégrale, ce que l’on peut apprécier d’autant plus qu’elles ont été superbement enregistrées ensemble en 1932, et que l’interprétation de l’Arietta conclusive de l’Opus 111 y est vraiment extraordinaire.

Pour le critique: ‘les deux premières sonates de la liste, celle en mi majeur Op.14 n°1 (n°9) et celle en ré majeur Op.10 n°3 (n°7), toutes deux de 1797, quand le compositeur n’avait pas encore atteint la trentaine, représentaient la phase antérieure de son développement. Les sonates en sol majeur Op.79 (n°25) et en fa dièse majeur Op.78 (n°24) servaient à illustrer la maîtrise qui était celle de Beethoven en 1809, alors que l’Opus 111 (n°32) a été réservée pour conclure le programme et toute la série, non seulement parce qu’il s’agissait de la dernière œuvre de Beethoven sous cette forme pour le piano, mais aussi parce qu’elle reste, à bien des égards, la plus grande de toutes les sonates. Cet ultime récital a une fois de plus mis en avant, sans nul doute, l’étonnante musicalité de Mr. Schnabel, qui est tellement évidente à tout instant dans ses interprétations que même le plus néophyte des auditeurs doit en percevoir quelque chose, alors qu’elle ne cesse de stupéfier le public des connaisseurs…… Avec toute l’appréciation qui était due à ce que Mr. Schnabel a accompli hier soir dans l’opus 111, c’est dans le superbe déroulement de la relativement négligée sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) que résidait sa prestation sa plus étonnante et la plus significative. Ici, Mr. Schnabel a revêtu le manteau impérial à la fois de pianiste et d’interprète. Peu de ceux qui ont entendu l’interprétation de la sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) risqueront de l’oublier, eu égard à son effet d’ensemble, ou bien par rapport à ses détails saillants. La sonate n’est pas entendue souvent, sans doute pour la raison que peu de pianistes la trouvent soit gratifiante, soit facile à unifier pour faire ressortir une relation positive entre ses deux mouvements. La perspicacité de Mr. Schnabel et sa compréhension de ses réelles possibilités ont donné une lecture qui a du re-créer l’œuvre pour chaque musicien dans la salle. Dans l’Allegro qui ouvrait l’œuvre et qui pour une fois n’était pas pris trop rapidement, il y avait des passages d’un charme sonore exceptionnel. Il en était de même des mesures de transition entre les deux sujets principaux pour lesquels les mélodies respectives à la main droite et à la main gauche étaient exquisement modelées sur un fond scintillant de doubles croches dans les accords brisés supérieurs qui était un ravissement pour l’oreille. Mais c’est dans le final que Mr. Schnabel a atteint son zénith à cette occasion. Il serait impossible d’exagérer la magie de ce mouvement, dans lequel la plupart des pianistes pataugent désespérément dans un marais de notes survolées sans signification aucune. Mr. Schnabel, avec sa relecture de cette division de l’œuvre, a enfin projeté une lumière réelle sur sa signification. Et quelle joie cela a été de l’entendre interprétée de sorte que la figuration élaborée qui relie les mouvements entre eux a pris forme et proportion sous les doigts experts du pianiste, d’où elle émergeait comme un moment brillant de bravoure de la plus haute espèce. La place manque pour discuter de la restitution de l’Op.111 (n°32), qui était carrément dramatique dans le premier mouvement et remarquablement originale à certains moments du dernier. Dans l’Arietta, le thème a été énoncé avec le son chantant, la tendresse et la simplicité qu’il exige, mais reçoit rarement. Mais particulièrement admirable était l’atmosphère mystérieuse de la quatrième variation et la délicatesse des figures murmurées de la cinquième variation. C’est avec ce caractère suprême que le pianiste a terminé son magnifique hommage au génie de Beethoven.’

The seventh program for the complete 32 Sonates of Beethoven by Artur Schnabel was comprised of the five above cited sonatas, the first two being, as for the other recitals, played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The seventh recital, given on 26 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, took place when, yet another event of the New York season, Arturo Toscanini pursued with Rudolf Serkin the series of his farewell concerts as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Schnabel’s performance of the sonata n°24 Op.78, dedicated to Therese von Brunswick, was of such a level that it almost ‘stole the show’ to Opus 111! (see below). Indeed, it was a stroke of genius by Schnabel to couple these two works to end his ‘marathon’, which we can appreciate all the more since they have been masterfuly recorded together in 1932, and since the recorded interpretation of the Arietta ending Opus 111 is really extraordinary.

For the critic:’ the first two sonatas on the list, that in E major, Op.14 n°1 (n°9), and that in D major, Op.10 n°3 (n°7), both stemming from 1797, when the composer was still in his twenties, represented the earlier phase of development. The sonatas in G major Op.79 (n°25) and in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) served to illustrate the mastery that was Beethoven’s in 1809, when these were written, while the Op.111 (n°32) was reserved to end the program and the series, not merely because it was Beethoven’s last work in the form for the piano, but because it remains in many respects the greatest of all sonatas. Ths culminating recital of the seven, once again published in no uncertain manner Mr. Schnabel’s astounding musicianship, which is so evident at every moment in his performances that the veriest tyro among his listeners must sense something of it, while it never ceases to amaze the connoisseurs in the audience…. With all due appreciation of what Mr. Schnabel accomplished in the Op.111 last night, his most startling and significant playing was heard in his superb unfolding of the rather neglected sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24). Here, Mr. Schnabel wore the imperial mantle both as pianist and as interpreter. Few who heard the interpretation of the sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) are likely to forget it, either in respect to its effect as a whole, or in regard to its salient details. The sonata is not often heard, for the reason, undoubtly, that few pianists find it either grateful, or easy to unify by bringing out a positive relation between its two movements. Mr. Schnabel’s insight and his understanding of its real possibilities, resulted in a reading which must have re-created the work for every musician in the house. There were passages in the opening Allegro (which, for once, was not taken too rapidly, as it usually is) of exceptional tonal charm. Such were the transitional measures between the two main subjects, where the respective melodies in the right and left hand were exquisitely molded against a glittering ripple of sixteenths in the upper broken chords that was fairly ravishing to the ear. But it was in the Finale that Mr. Schnabel reached his zenith on this occasion. It would be impossible to overstate his wizardy in this movement, where most pianists flounder hopelessly in a morass of flying notes meaning nothing. Mr. Schnabel, in his re-editing of this division of the work, has at last thrown some real light on its meaning. And what a joy it was to have it performed so that the elaborate figuration that binds the movements together took on shape and proportion under the pianist’s knowing fingers, whence it emerged as a coruscating bit of bravura of the highest type. There is no space to go into a discussion of Mr. Schnabel’s rendition of the Opus 111, which was emphatically dramatic in the first movement and strikingly original in certain phases of the last. In the Arietta, the theme was stated with the singing tone, the tenderness and simplicity it demands and seldom receives. But especially admirable were the mysterious atmosphere created in the fourth variation and the ineffable delicacy of the purling figures of the fifth variant. By art of this superlative nature the pianist completed his splendid tribute to Beethoven’s genius.’

____________

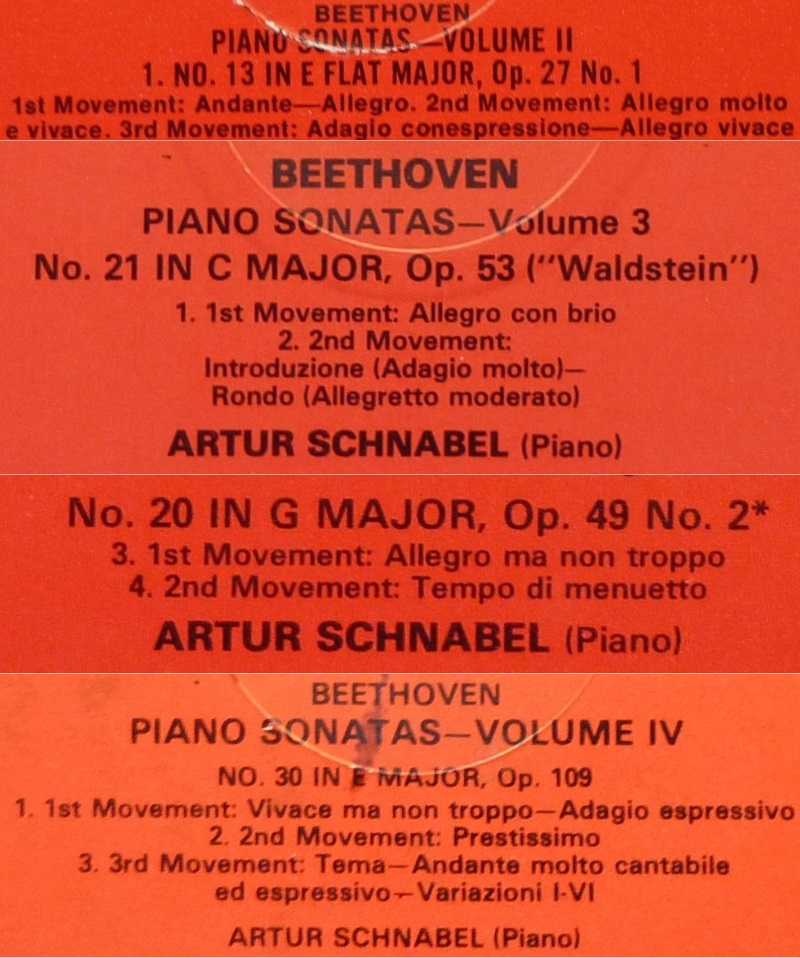

Sonate n°13 Op.27 n°1: 1 Novembre 1932

Sonate n°21 Op.53: 25 Avril & 7 Mai 1934

Sonate n°20 Op.49 n°2: 12 Avril 1933

Sonate n°30 Op.109: 7 Mai 1932

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Schnabel London 1932

Le sixième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel était beaucoup plus court (68′) que le précédent (100′), mais il proposait une très grande Sonate (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) à la fin de chaque partie. La Sonate n°21 Op.53 est la dernière œuvre qu’il a jouée en public (concert du 20 janvier 1951 au Hunter College de New York).

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Une des caractéristiques du jeu de Schnabel, qui n’a pas été soulignée par les critiques new-yorkais, mais que l’on perçoit très bien sur ces reports, est la beauté des pianissimi, remarquables aussi bien par la qualité du timbre que par leur densité de son.

Pour le sixième récital, donné le 19 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarque que Schnabel a bien rendu le caractère enchanteur et romantique de la sonate en si bémol majeur (n°13 Op.27 n°1) et a joué la modeste sonate en sol majeur (n°20 Op.49 n°2) avec la légèreté et le charme qui conviennent à son expression sans apprêt. ‘Mais, c’est avec les deux autres sonates que Mr. Schnabel était confronté au plus grand Beethoven, et c’est dans celles-ci que ses interprétations avaient l’incandescence et la profondeur dignes du compositeur. Le mouvement qui ouvre la sonate en do majeur (n°21 Op.53) était pris un peu plus rapidement que la plupart des pianistes. La puissance et le joie de vivre de la musique justifient cete option, dans la mesure où une allure impétueuse ne mène pas à rendre confus les passages vertigineux. Ceux-ci, sous les doigts de Mr. Schnabel, n’étaient pas confus. Plus encore, la musique était présentée avec une clarté cristalline, avec des nuances délicates et aucun manque d’enthousiasme et de propulsion. L’Adagio était angoissé dans sa réserve, et le dernier mouvement, comme le premier, était un tour de force d’animation et de lyrisme. Si le Beethoven de la ‘Waldstein’ était communiqué avec tout le brio et l’audace de sa robuste maturité, que dire alors du jeu de Mr. Schnabel dans la sonate en mi majeur (n°30 Op.109), musique dans laquelle Beethoven a atteint une incomparable liberté d’imagination? C’était une interprétation d’une portée incandescente, avec le noble Andante rendu avec émotion. Alors que Mr. Schnabel était arrivé au terme des dernières pages apocalyptiques avec leur mélange de sérénité et de tristesse, l’auditoire est resté silencieux. Il a fallu un moment pour rompre la magie. Et alors Mr. Schnabel reçut un tonnerre d’applaudissements, comme à la fin de la ‘Waldstein’, et comme ça a été également le cas tout au long de ce remarquable marathon.’

The sixth program of Artur Schnabel’s complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas was much shorter (68′) than the preceding one (100′), but it offered a very great Sonata (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) at the end of each part. The Sonata n°21 Op.53 is the last work he performed in public (concert of 20 January 1951 at Hunter College in New York).

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

One of the highlights of Schnabel’s playing, not underlined by the New-York critics, but well reproduced on these transfers, is the beauty of the pianissimi, outstanding as to the quality of the timbre as well as to their density of sound.

For the sixth recital given on 19 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarks that Schnabel captured the enchanting, romantic spirit of the E flat major sonata (n°13 Op.27 n°1) and played the unpretentious G major sonata (n°20 Op.49 n°2) with the lightness and charm that its unashamed sentiment required. ‘But it was in the other two sonatas that Mr. Schnabel had the greater Beethoven to contend with, and it was in these that his interpretations had the incandescence and penetration that where worthy of the composer. The opening movement of the C major sonata (n°21 Op.53) was taken a shade faster than the tempi of many pianists. The power and exhilaration of the music justify this procedure, provided a headlong pace does not cause the vertiginous passages to be blurred. They were not blurred under Mr. Schnabel’s hands. More, the music was set forth with crystalline clarity, with delicate nuance and with no loss of fire or propulsion. The Adagio was anguished in its restraint, and the last movement, like the first, was a tour de force of animation and lyricism. If the Beethoven of the ‘Waldstein’ was communicated with all the gusto and daring of his robust maturity, what is there to say of Mr. Schnabel’s playing of the E major sonata (n°30 Op.109), music in which Beethoven had achieved incomparable freedom of the imagination? It was an interpretation of glowing comprehension, with the noble Andante movingly communicated. As Mr. Schnabel concluded the final apocalyptic pages with their intermingling of serenity and sorrow, the audience remained hushed. It was several moments before the spell was broken. Then, Mr. Schnabel was thunderously applauded, as he was at the end of the ‘Waldstein’, and as he has been throughout this remarkable marathon’.

Extrait du programme du Concert/ From Concert program: Schnabel BBC SO/A. Boult Queen’s Hall 15 February 1933