Auteur/autrice : C&A HD

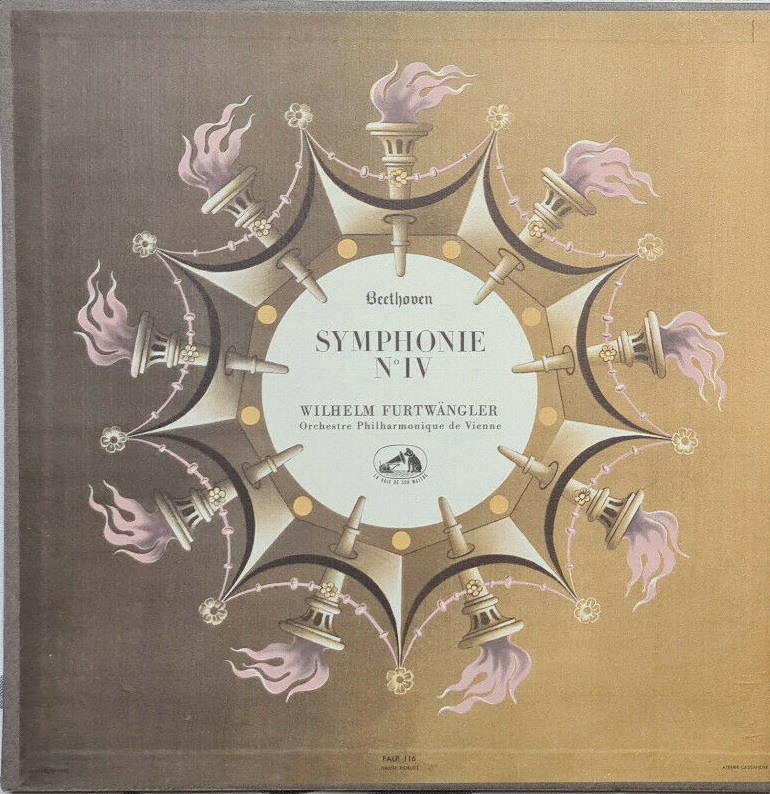

Wilhelm Furtwängler – Wiener Philharmoniker

Wien Musikvereinsaal – 25 & 30 Januar 1950

Prod: Walter Legge – Eng: Anthony Griffith

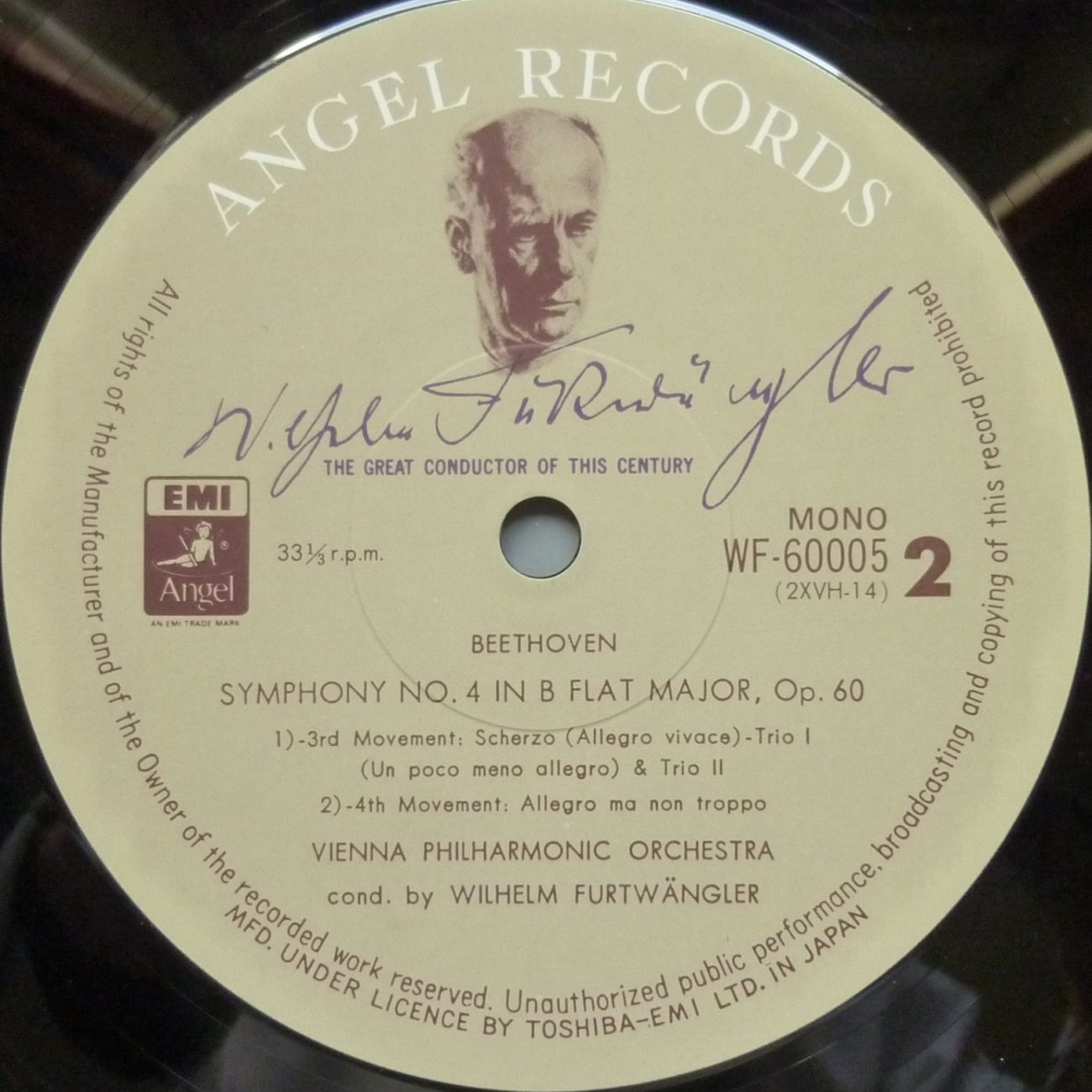

Source: EMI-Toshiba Angel WF-60005

Furtwängler a enregistré deux fois cette symphonie pour le disque, en 1950 et en 1952. On ne sait pas exactement pourquoi il a décidé de refaire cet enregistrement (1 et 2 décembre 1952). Toujours est-il que la nouvelle interprétation est nettement inférieure à la précédente, mais pour ses éditions internationales, c’est toujours l’enregistrement de 1952 qu’ EMI/HMV a utilisé, et il a fallu attendre le récent coffret Warner pour que la version de 1950 soit enfin de nouveau largement disponible, mais dans un son qui n’est guère satisfaisant en raison notamment d’une audible détérioration de la bande originale 76 cm/s.

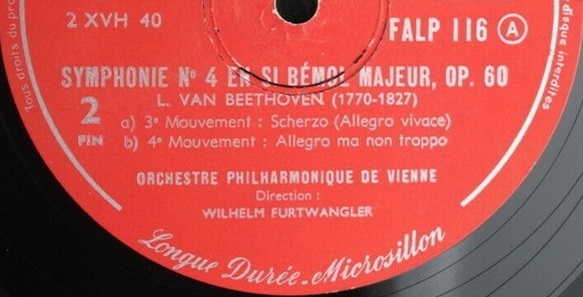

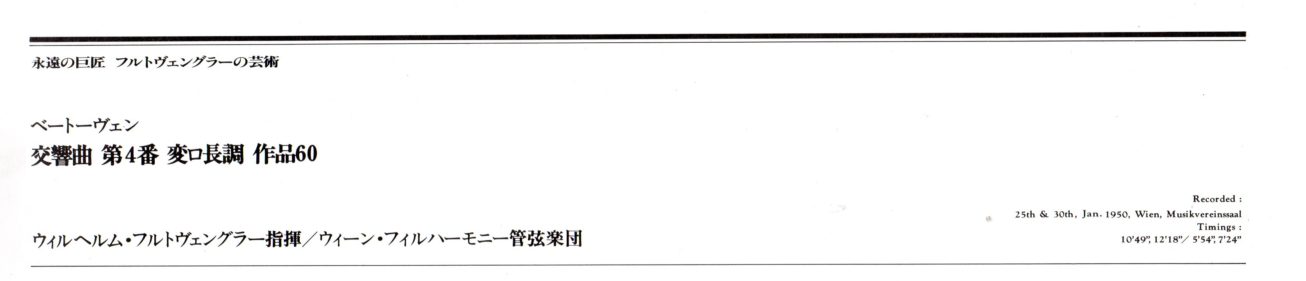

La version de 1950 a tout d’abord été publiée sur 78 tours. En microsillon, il n’y a alors eu qu’une seule et unique édition, en France, sous la référence FALP 116 avec les numéros de matrice 2 XVH 13 et 14:

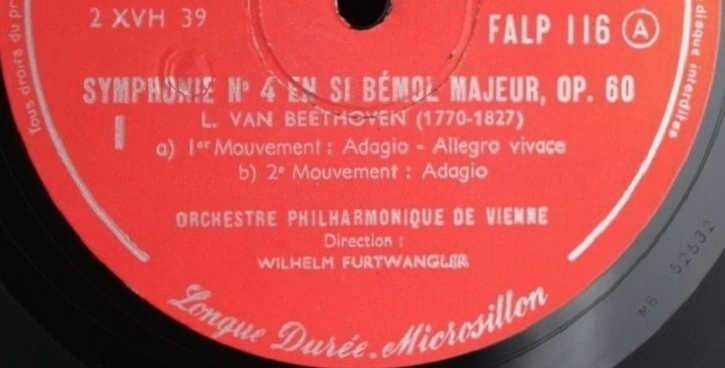

En juin 1953, la deuxième version a été publiée en microsillon sous la référence britannique ALP1059. En avril 1954, la référence FALP 116 a de manière surprenante été ré-utilisée pour la publication en France de la seconde version, avec cette fois les numéros de matrice 2 XVH 39 et 40:

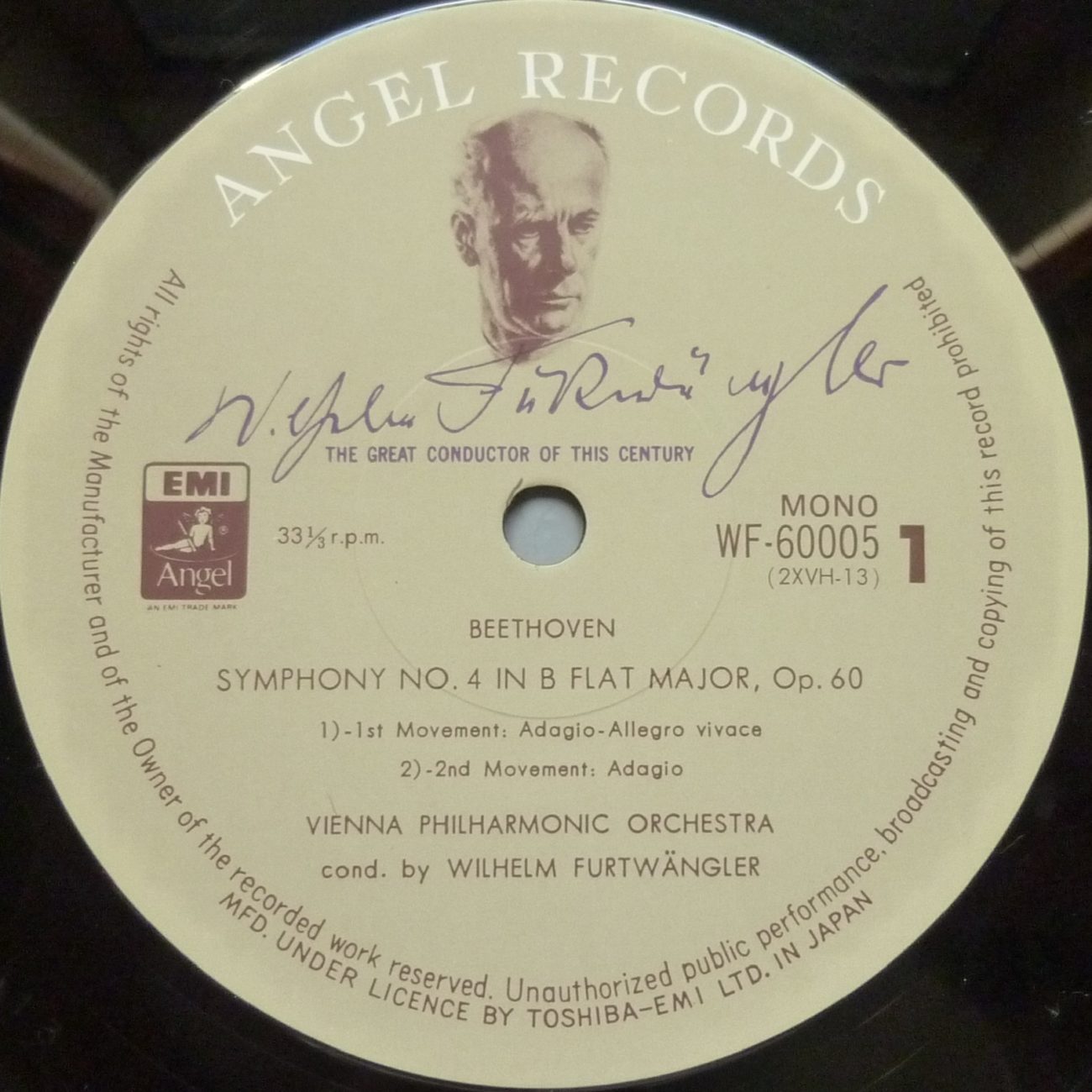

C’est en 1980 au Japon (EMI-Toshiba WF-60005 sous le label Angel) et en Italie (EMI Italiana 3C 153 53800-5M), qu’ont été publiées les seules autres éditions officielles en microsillon de la version de 1950. Le disque japonais, dans un son superbe, constitue la meilleure source accessible à ce jour, car le microsillon italien est pratiquement introuvable et le CD TOCE-6180 publié ultérieurement par EMI au Japon n’atteint pas le même niveau de qualité.

Sur les étiquettes, on remarque qu’ EMI/Toshiba reprend les numéros de matrice 2 XVH 13 et 14, mais il s’agit en fait d’une nouvelle gravure pour l’édition de 1980.

____________

Furtwängler has commercially recorded this symphony twice, in 1950 and in 1952. It is not quite clear why he decided to make another recording thereof (1 and 2 December 1952). Be it as it may, the second recording is clearly less succesful than the first one, but, for its international editions, it was always the 1952 version which EMI/HMV used, and it was not until the recent Warner boxset that the 1950 version has at last been made widely available, but with a sound that is less than optimal, partly due to a noticeable deterioration of the 30 ips master tape.

The 1950 version was firstly published on 78 rpm records. There was then only a single LP edition, namely for France, with reference number FALP 116 and matrix numbers 2 XVH 13 et 14.

In June 1953, the second version was published in England as a LP with reference number ALP1059. In April 1954, reference number FALP 116 was surprisingly enough used again for the publication in France of the second version, but this time with matrix numbers 2 XVH 39 et 40.

In 1980 in Japan (EMI-Toshiba WF-60005 under the label Angel) and in Italy (EMI Italiana 3C 153 53800-5M), were published the only other official LP editions of the 1950 version. The Japanese LP, in superior sound, is the best now available source, since the EMI-Italiana LP is almost impossible to find and since the CD TOCE-6180 later published by EMI in Japan does quite reach the same quality level.

On the LP labels, EMI/Toshiba uses matrix numbers 2 XVH 13 and 14, but of course the matrixes have been newly cut for the 1980 edition.

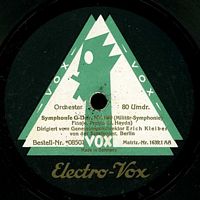

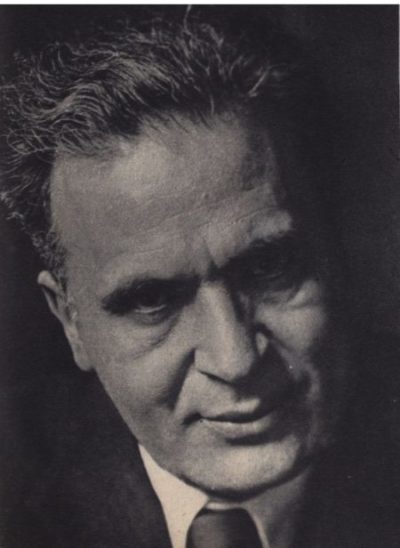

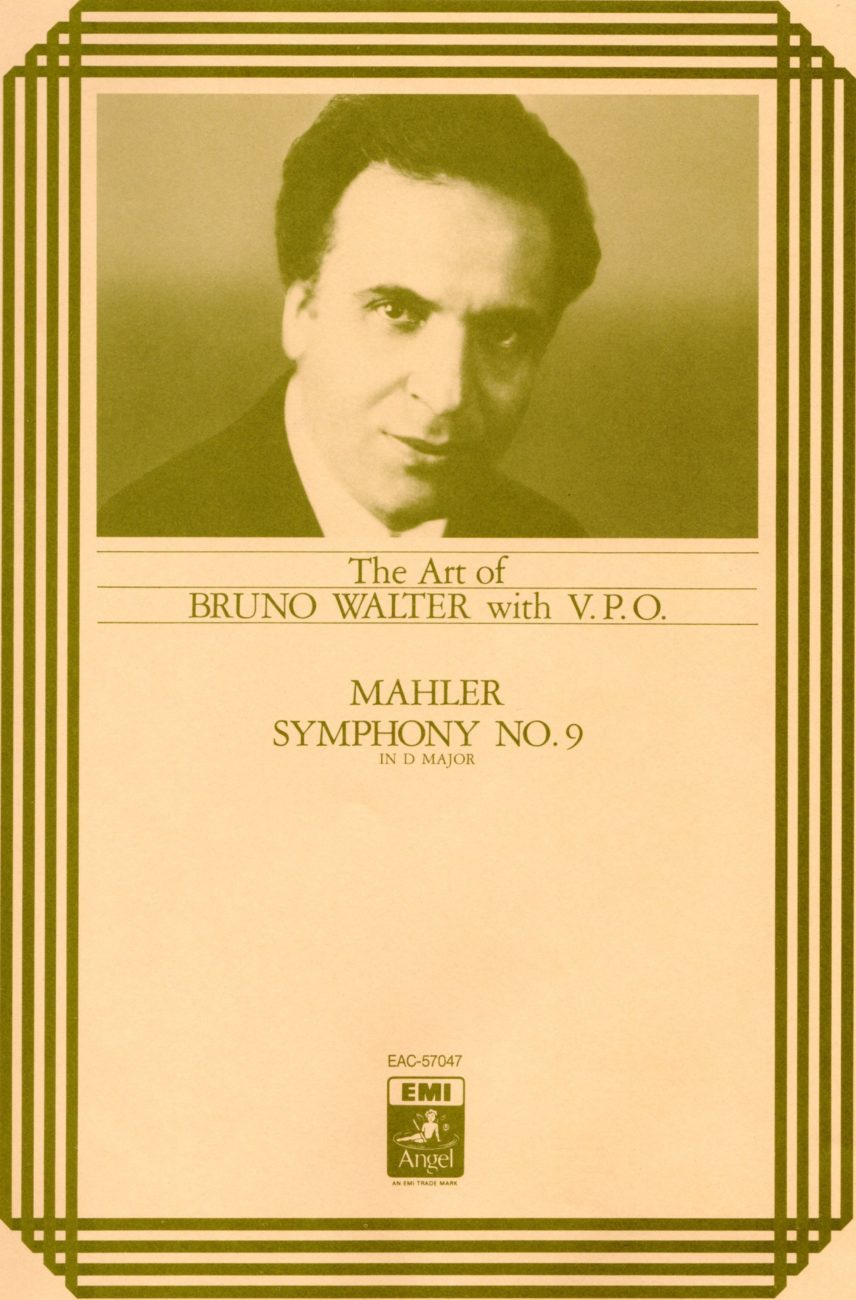

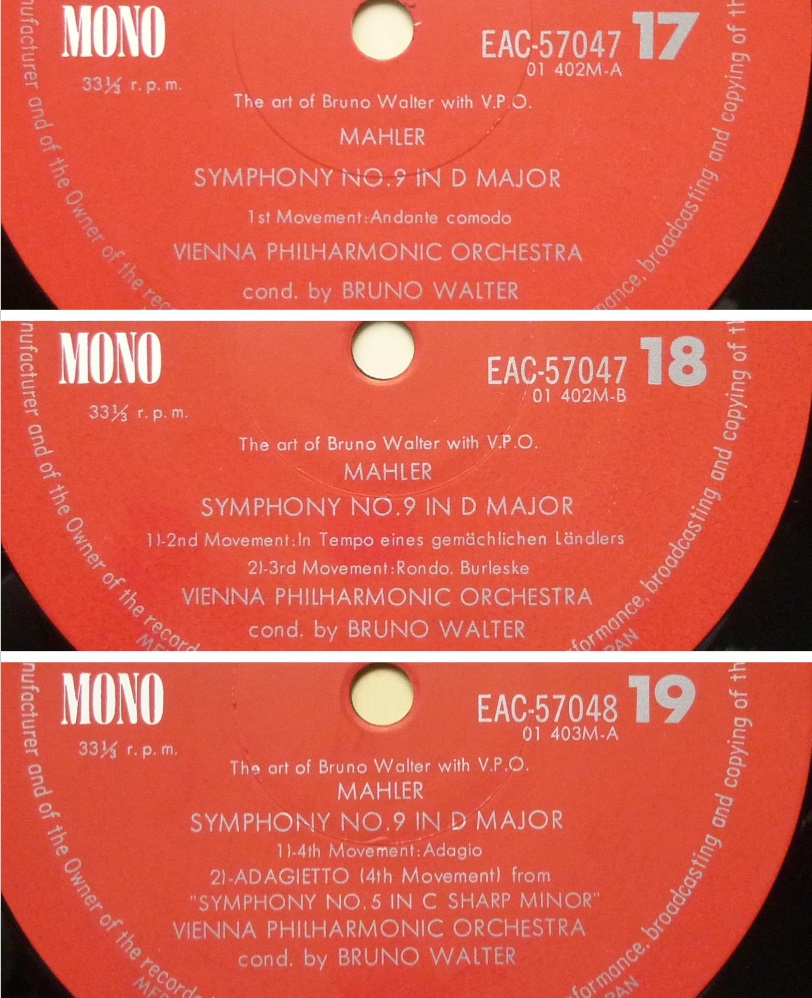

Walter – IV – Mahler Symphonie n°9 WPO

Musikvereinsaal – 16 Januar (Jänner) 1938

Source: 33t. Angel Japan « The Art of Bruno Walter with WPO »

Cette interprétation mahlérienne à la fois intense et sobre, captée en public, est un document inestimable.

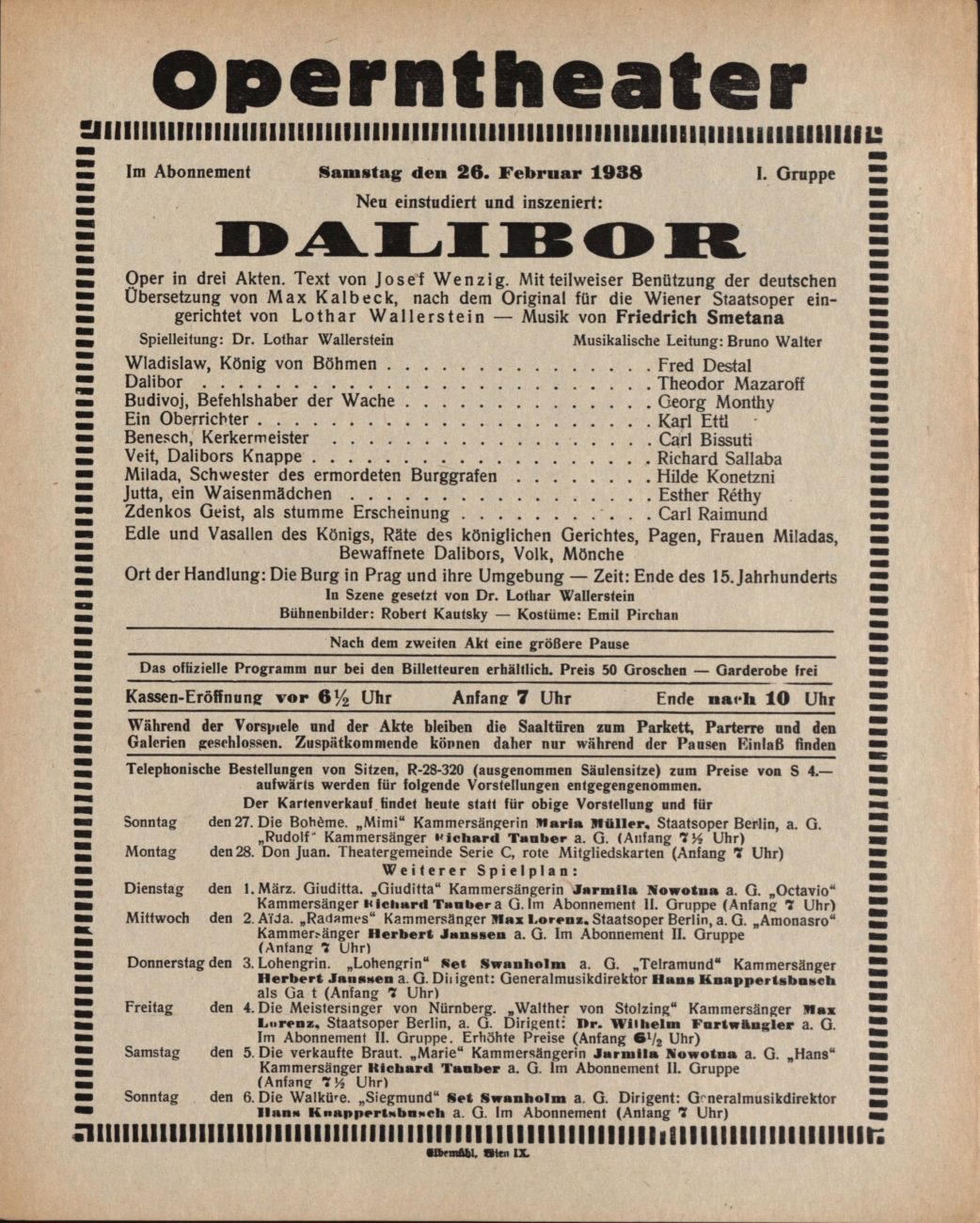

En janvier et février 1938, avant de partir comme chaque année à pareille époque depuis 1933 pour une série de concerts du 3 au 19 mars 1938 avec le Concertgebouworkest d’ Amsterdam, Bruno Walter a dirigé à Vienne des concerts au Musikverein et des représentations au Staatsoper, ainsi qu’un ultime concert à Budapest, selon le calendrier suivant:

6 Janvier Staatsoper: Bizet Carmen

8 Janvier Staatsoper: Verdi Don Carlos

15 & 16 Janvier Musikvereinsaal: Mozart Symphonie n°41 – Mahler Symphonie n°9

17 Février Staatsoper: Weber Oberon

19 & 20 Février Musikvereinsaal: Mendelssohn Sommernachtstraum Ouv. – Wellesz Prosperos Beschwörungen Op.53 – Bruckner Symphonie n°4 (3 ème Version 1888)

21 Février Budapest Theatre Erkel: Mozart Symphonie n°35 – Strauss Don Juan – Bruckner Symphonie n°4 (3 ème Version 1888)

26 Février Staatsoper: Smetana Dalibor (Nouvelle production de Lothar Wallerstein Première)

Cette représentation de Dalibor de Smetana sera la dernière prestation de Bruno Walter à Vienne avant l’Anschluss et son exil forcé.

This intense and yet classical live recorded Mahler performance is an invaluable document.

In January and February, before leaving for Amsterdam like he did each year at the same period since 1933 for a series of concerts from 3 to 19 March 1938 with the Concertgebouworkest, Bruno Walter conducted in Vienna concerts at the Musikverein and at the Staatsoper, as well as a valedictory concert in Budapest, according to the following schedule:

January 6 Staatsoper: Bizet Carmen

January 8 Staatsoper: Verdi Don Carlos

January 15 & 16 Musikvereinsaal: Mozart Symphony n°41 – Mahler Symphony n°9

February17 Staatsoper: Weber Oberon

February 19 & 20 Musikvereinsaal: Mendelssohn Sommernachtstraum Ouv. – Wellesz Prosperos Beschwörungen Op.53 – Bruckner Symphony n°4 (3rd Version 1888)

February 21 Budapest Theatre Erkel: Mozart Symphony n°35 – Strauss Don Juan – Bruckner Symphony n°4 (3rd Version 1888)

February 26 Staatsoper: Smetana Dalibor (New production by Lothar Wallerstein Première)

This performance of Smetana’s Dalibor was to be Bruno Walter’s last performance in Vienna before the Anschluss and his forced exile.

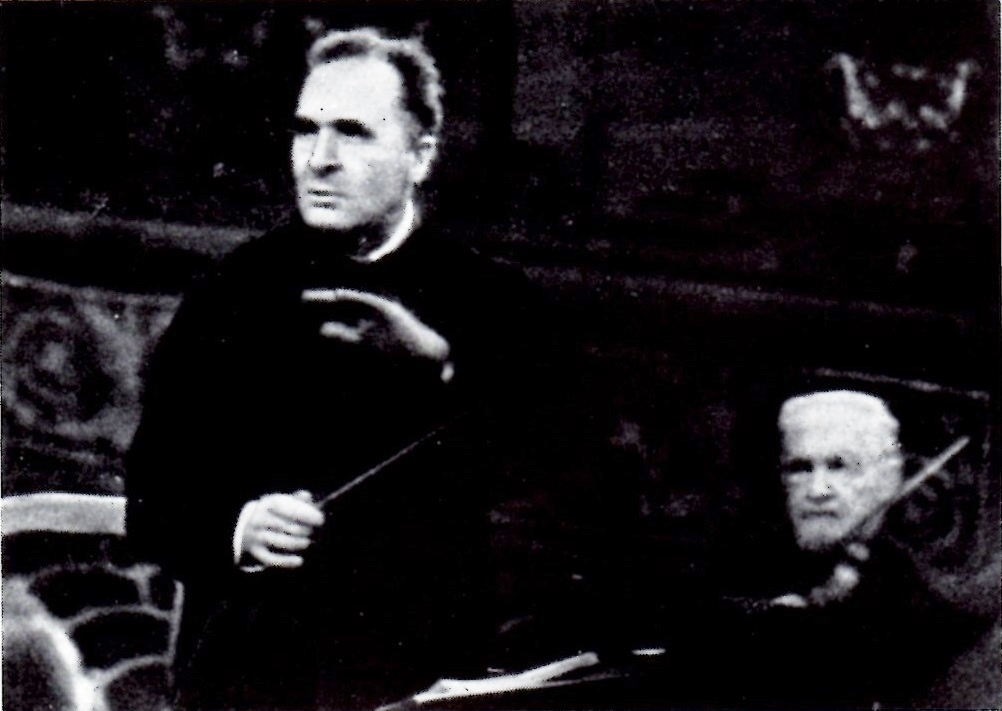

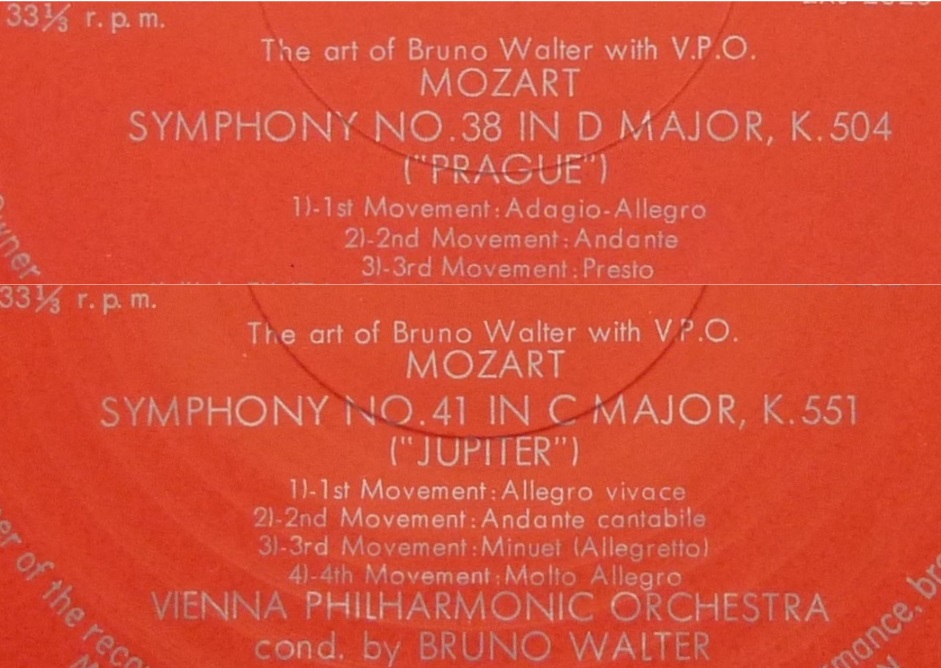

Mozart

Symphonie n°38 K.504 WPO Musikvereinsaal 18 Dezember 1936

Symphonie n°41 K.551 WPO Musikvereinsaal 11 Januar (Jänner) 1938

Source: 33t. Angel Japan « The Art of Bruno Walter with WPO »

Bruno Walter & Arnold Rosé

________

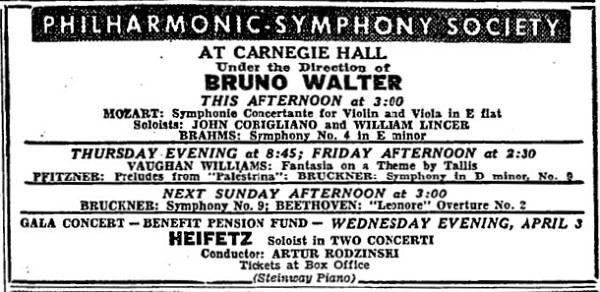

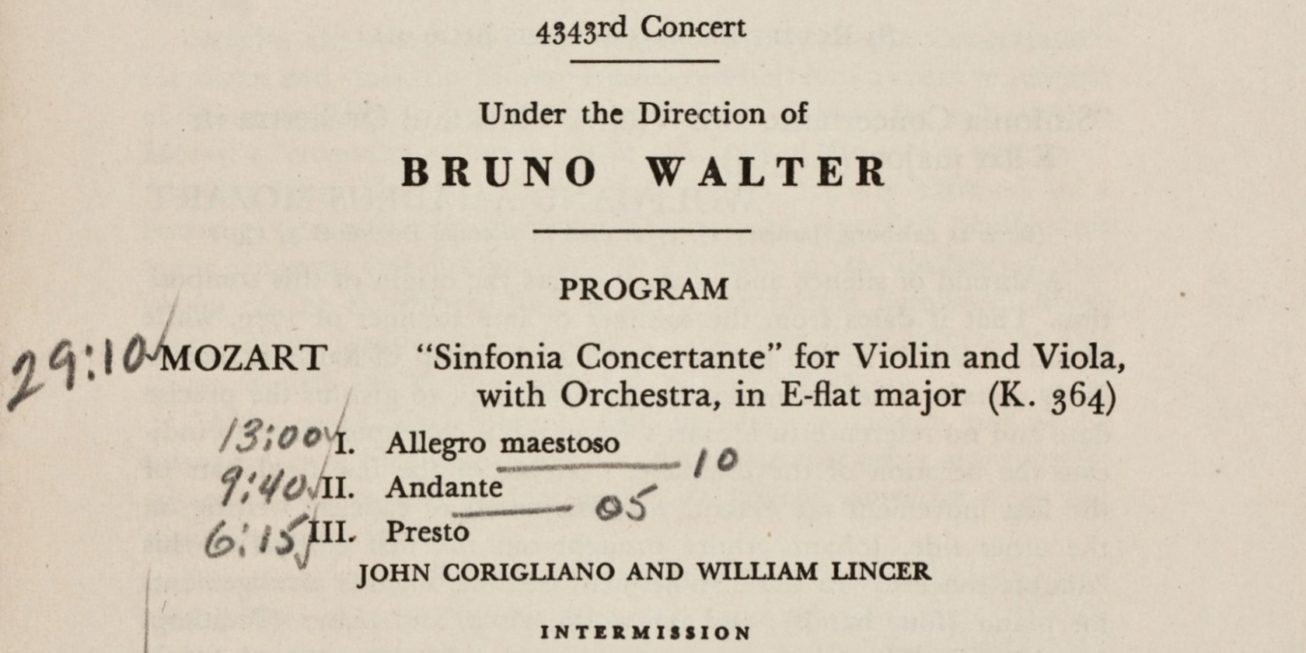

Sinfonia Concertante K.364 NYPO John Corigliano & William Lincer Carnegie Hall 10 March 1946 Source: Bande/Tape (origine: disques/transcription discs)

William Lincer & John Corigliano

________

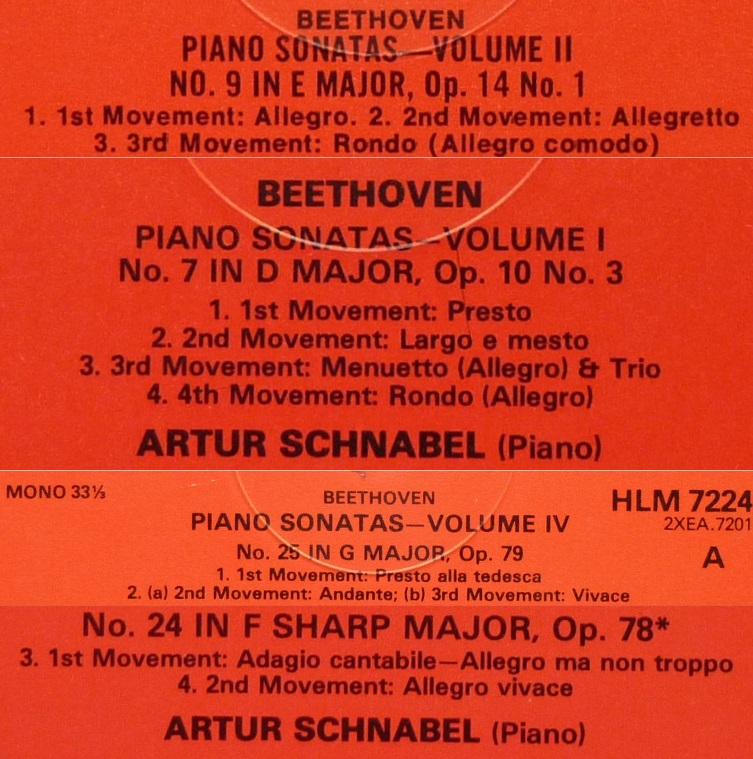

Ces trois enregistrements de Bruno Walter représentent la fin de son activité à Vienne avant la guerre, la Symphonie n°41 accompagnant les 15 et 16 janvier la Neuvième de Mahler au cours de sa dernière série de concerts avant l’Anschluss, ainsi que son unique enregistrement accessible de la Symphonie Concertante pour violon et alto K.364 lors du concert du 10 mars 1946. Il avait déjà dirigé cette œuvre à New York les 5 et 6 mars 1925 avec en solistes Samuel Duskin et Lionel Tertis, et il l’a redonnée les 12 et 13 février 1953 avec Corigliano et Lincer, mais sans retransmission radiophonique à cette occasion. Un enregistrement de concert à Chicago (concert télévisé du 25 janvier 1956 avec John Weicher et Milton Preeves) a été recensé dans une archive privée, mais n’a pas été publié. Le concert du dimanche 10 mars 1946 est particulier en ce sens que son programme (Mozart K364, Brahms Symphonie n°4) est complètement différent de celui des concerts des 7 et 8 mars consacrés à la Passion selon St-Matthieu de Bach, alors qu’en général, le programme radiodiffusé le dimanche reprend en partie le programme de la semaine.

Concernant l’interprétation de la Sinfonia Concertante de Mozart, le critique Noel Straus écrivait: ‘John Corigliano, le concertmaster de l’orchestre, et William Lincer, son premier alto, ont été les solistes de l’opus de Mozart, qui, comme le Brahms, a bénéficié d’une lecture des plus élaborées et des plus élevées. Aucune interprétation ne peut être d’un esprit aussi complètement mozartien que celle qui a été donnée de la Sinfonia Concertante, une oeuvre unique en son genre qui n’a rien perdu de sa fraîcheur juvénile et de son grand attrait au cours des 167 années qui se sont écoulées depuis sa composition. Sous une direction moins, cette composition exquisément façonnée peut facilement dégénérer de la part des deux solistes en une exhibition de virtuosité. Même si une bravoure experte était apportée aux mesures en solo, la musique elle-même et la révélation de sa pleine signification étaient le souci principal de Mr. Walter, et il a montré que c’était possible sans exagérer la composante soliste, avec pour résultat qu’un parfait sens de l’équilibre, rarement obtenu dans cette oeuvre à l’orchestration légère, a été rendu possible. Avec cette manière de faire, la composition a gagné en intimité, et rien n’a été oublié pour projeter le caractère sensible et poétique de son contenu. L’art et la compétence technique de Mr. Corigliano et de Mr. Lincer étaient si complètement en harmonie, leurs sonorités si subtilement intégrées et équilibrées, que leurs jeux formaient remarquablement un tout, et s’inscrivaient en même temps dans le cadre dynamique qui convenait exactement à la fusion avec un accompagnement orchestral finement conçu. Il est difficile d’imaginer un rendu plus éloquent et plus convaincant, ou plus admirable par sa pureté tonale, la beauté de sa texture, par ses couleurs et par son expressivité.’

These three Bruno Walter recordings illustrate the end of his pre-war tenure in Vienna, the Symphony n°41 being played on the 15 and 16 January together with the Mahler Ninth during his last series of concerts there before the Anschluss, as well as his only available recording of the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola K.364 during the concert of March 10, 1946. He already conducted this work in New York on 5 and 6 March 1925 with Samuel Duskin and Lionel Tertis as soloists, and he performed it again on 12 and 13 February 1953 with Corigliano et Lincer, but without broadcast this time. A concert recording in Chicago (TV concert on 25 January 1956 with John Weicher and Milton Preeves) has been listed in a private archive, but hasn’t been published. The concert of Sunday 10 March 1946 is special in the sense that its program (Mozart K.364, Brahms Symphony n°4) is entirely different from the preceding ones on 7 and 8 March dedicated to Bach’s Passion according to St-Matthew, whereas usually, the program of the Sunday broadcast is partly comprised of works played during the week.

Concerning the performance of the Sinfonia Concertante by Mozart, music critic Noel Straus wrote: ‘John Corigliano, the orchestra’s concertmaster and William Lincer, its first viola, were the soloists in the Mozart opus, which, like the Brahms work, gloried in a reading of a most searching and exalted nature. No performance could be more completely Mozartean in spirit than that given of the Sinfonia Concertante, an unrivaled work of its genre that has lost nothing of its youthful freshness and deep appeal with the passage of the 167 years since its creation. Under less fully comprehending direction, the exquisitely wrought composition easily can become first and foremost an exhibition of virtuosity on the part of the two soloists. But for all the expertness of bravoura brought to the solo measures, the music itself and the revelation of its meaning to the full was the primary consideration with Mr. Walter and this he found possible without overstressing the solo element with the result that a perfect sense of balance, rarely achieved in this lightly orchestrated score, became possible. The composition gained in intimacy through this type of treatment, and nothing was left undone to project the sensitive, poetic character of its content. The artistry and skill of Mr. Corigliano and Mr. Lincer was so perfectly matched, their tone so subtly integrated and equalized, that their playing proved remarkably unified, and at the same time was held in just the right dynamic frame to blend absolutely with the finely considered orchestral support. It is difficult to conceive of a presentation of this work more eloquent and persuasive, or more admirable in tonal purity, beauty of texture, coloring and expressiveness.’

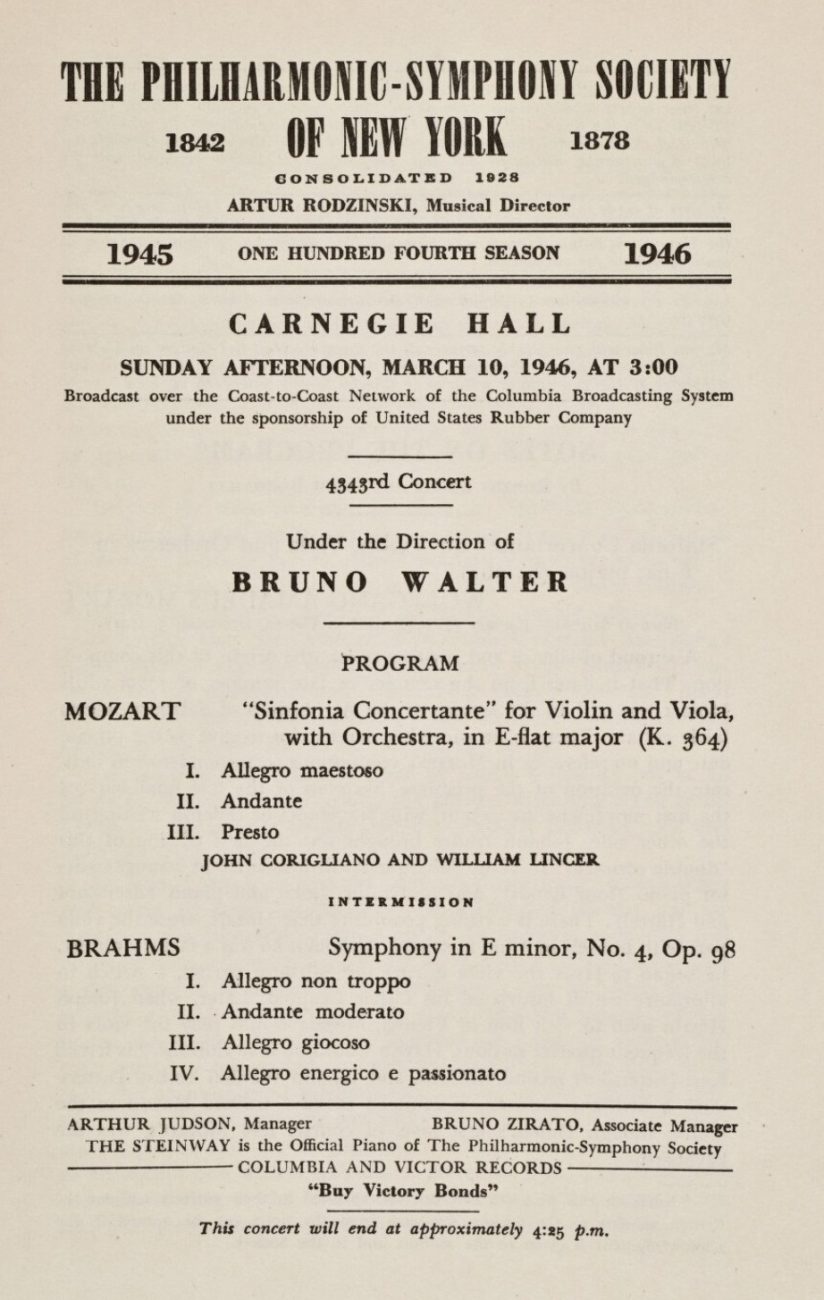

Sonate n°9 Op.14 n°1: 25 Mars 1932

Sonate n°7 Op.10 n°3: 12 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°25 Op.79: 15 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°24 Op.78: 21 Mars 1932

Sonate n°32 Op.111: 21 Janvier, 21 & 22 Mars, 7 Mai 1932

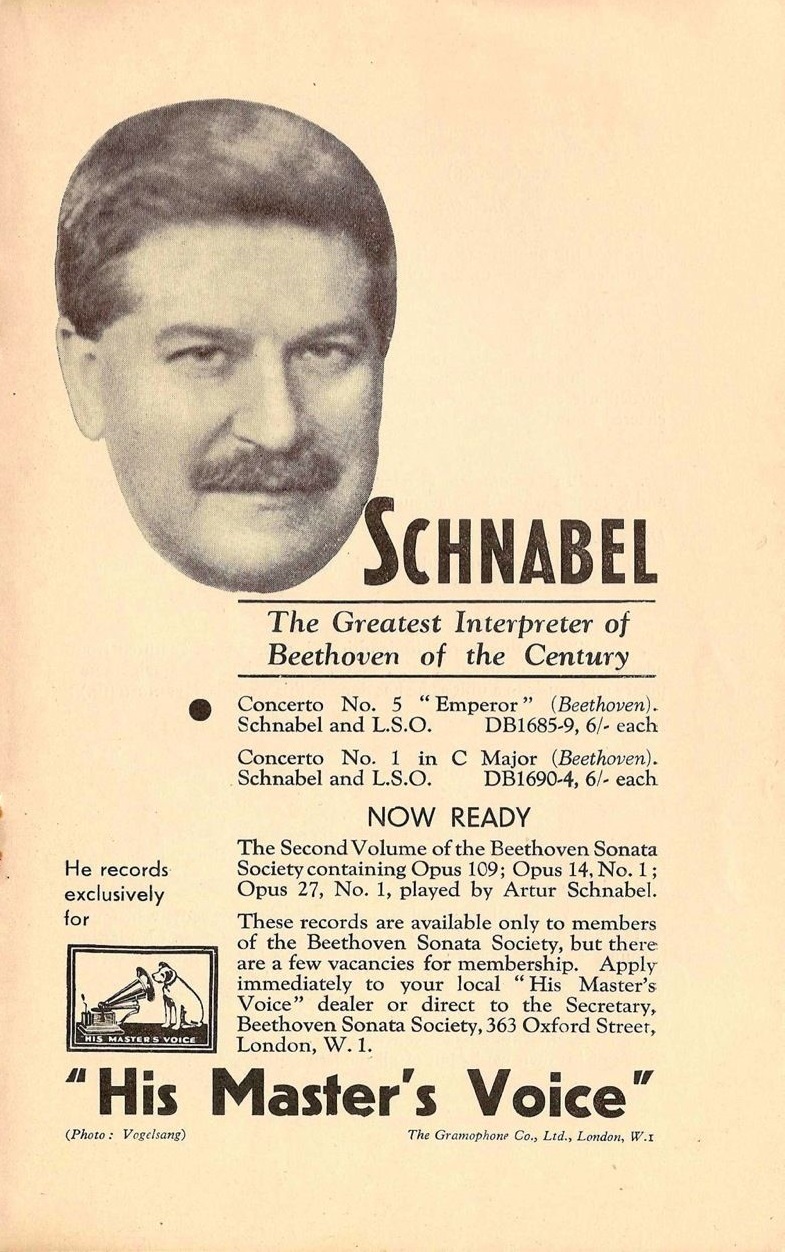

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le septième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comprenait les cinq sonates ci-dessus, les deux premières étant, comme pour les autres récitals, jouées avant l’entracte.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le septième récital, donné le 26 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, a eu lieu au moment où, autre événement de la saison new-yorkaise, Arturo Toscanini poursuivait avec Rudolf Serkin la série de ses concerts d’adieu en tant que chef titulaire du New York Philharmonic. L’interprétation par Schnabel de la sonate n°24 Op.78, dédiée à Therese von Brunswick, a atteint un niveau tel qu’elle a presque ‘ volé la vedette’ à l’Opus 111! (voir la critique ci-dessous). Une idée de génie de la part de Schnabel que d’associer ces deux œuvres pour terminer son intégrale, ce que l’on peut apprécier d’autant plus qu’elles ont été superbement enregistrées ensemble en 1932, et que l’interprétation de l’Arietta conclusive de l’Opus 111 y est vraiment extraordinaire.

Pour le critique: ‘les deux premières sonates de la liste, celle en mi majeur Op.14 n°1 (n°9) et celle en ré majeur Op.10 n°3 (n°7), toutes deux de 1797, quand le compositeur n’avait pas encore atteint la trentaine, représentaient la phase antérieure de son développement. Les sonates en sol majeur Op.79 (n°25) et en fa dièse majeur Op.78 (n°24) servaient à illustrer la maîtrise qui était celle de Beethoven en 1809, alors que l’Opus 111 (n°32) a été réservée pour conclure le programme et toute la série, non seulement parce qu’il s’agissait de la dernière œuvre de Beethoven sous cette forme pour le piano, mais aussi parce qu’elle reste, à bien des égards, la plus grande de toutes les sonates. Cet ultime récital a une fois de plus mis en avant, sans nul doute, l’étonnante musicalité de Mr. Schnabel, qui est tellement évidente à tout instant dans ses interprétations que même le plus néophyte des auditeurs doit en percevoir quelque chose, alors qu’elle ne cesse de stupéfier le public des connaisseurs…… Avec toute l’appréciation qui était due à ce que Mr. Schnabel a accompli hier soir dans l’opus 111, c’est dans le superbe déroulement de la relativement négligée sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) que résidait sa prestation sa plus étonnante et la plus significative. Ici, Mr. Schnabel a revêtu le manteau impérial à la fois de pianiste et d’interprète. Peu de ceux qui ont entendu l’interprétation de la sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) risqueront de l’oublier, eu égard à son effet d’ensemble, ou bien par rapport à ses détails saillants. La sonate n’est pas entendue souvent, sans doute pour la raison que peu de pianistes la trouvent soit gratifiante, soit facile à unifier pour faire ressortir une relation positive entre ses deux mouvements. La perspicacité de Mr. Schnabel et sa compréhension de ses réelles possibilités ont donné une lecture qui a du re-créer l’œuvre pour chaque musicien dans la salle. Dans l’Allegro qui ouvrait l’œuvre et qui pour une fois n’était pas pris trop rapidement, il y avait des passages d’un charme sonore exceptionnel. Il en était de même des mesures de transition entre les deux sujets principaux pour lesquels les mélodies respectives à la main droite et à la main gauche étaient exquisement modelées sur un fond scintillant de doubles croches dans les accords brisés supérieurs qui était un ravissement pour l’oreille. Mais c’est dans le final que Mr. Schnabel a atteint son zénith à cette occasion. Il serait impossible d’exagérer la magie de ce mouvement, dans lequel la plupart des pianistes pataugent désespérément dans un marais de notes survolées sans signification aucune. Mr. Schnabel, avec sa relecture de cette division de l’œuvre, a enfin projeté une lumière réelle sur sa signification. Et quelle joie cela a été de l’entendre interprétée de sorte que la figuration élaborée qui relie les mouvements entre eux a pris forme et proportion sous les doigts experts du pianiste, d’où elle émergeait comme un moment brillant de bravoure de la plus haute espèce. La place manque pour discuter de la restitution de l’Op.111 (n°32), qui était carrément dramatique dans le premier mouvement et remarquablement originale à certains moments du dernier. Dans l’Arietta, le thème a été énoncé avec le son chantant, la tendresse et la simplicité qu’il exige, mais reçoit rarement. Mais particulièrement admirable était l’atmosphère mystérieuse de la quatrième variation et la délicatesse des figures murmurées de la cinquième variation. C’est avec ce caractère suprême que le pianiste a terminé son magnifique hommage au génie de Beethoven.’

The seventh program for the complete 32 Sonates of Beethoven by Artur Schnabel was comprised of the five above cited sonatas, the first two being, as for the other recitals, played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The seventh recital, given on 26 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, took place when, yet another event of the New York season, Arturo Toscanini pursued with Rudolf Serkin the series of his farewell concerts as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Schnabel’s performance of the sonata n°24 Op.78, dedicated to Therese von Brunswick, was of such a level that it almost ‘stole the show’ to Opus 111! (see below). Indeed, it was a stroke of genius by Schnabel to couple these two works to end his ‘marathon’, which we can appreciate all the more since they have been masterfuly recorded together in 1932, and since the recorded interpretation of the Arietta ending Opus 111 is really extraordinary.

For the critic:’ the first two sonatas on the list, that in E major, Op.14 n°1 (n°9), and that in D major, Op.10 n°3 (n°7), both stemming from 1797, when the composer was still in his twenties, represented the earlier phase of development. The sonatas in G major Op.79 (n°25) and in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) served to illustrate the mastery that was Beethoven’s in 1809, when these were written, while the Op.111 (n°32) was reserved to end the program and the series, not merely because it was Beethoven’s last work in the form for the piano, but because it remains in many respects the greatest of all sonatas. Ths culminating recital of the seven, once again published in no uncertain manner Mr. Schnabel’s astounding musicianship, which is so evident at every moment in his performances that the veriest tyro among his listeners must sense something of it, while it never ceases to amaze the connoisseurs in the audience…. With all due appreciation of what Mr. Schnabel accomplished in the Op.111 last night, his most startling and significant playing was heard in his superb unfolding of the rather neglected sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24). Here, Mr. Schnabel wore the imperial mantle both as pianist and as interpreter. Few who heard the interpretation of the sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) are likely to forget it, either in respect to its effect as a whole, or in regard to its salient details. The sonata is not often heard, for the reason, undoubtly, that few pianists find it either grateful, or easy to unify by bringing out a positive relation between its two movements. Mr. Schnabel’s insight and his understanding of its real possibilities, resulted in a reading which must have re-created the work for every musician in the house. There were passages in the opening Allegro (which, for once, was not taken too rapidly, as it usually is) of exceptional tonal charm. Such were the transitional measures between the two main subjects, where the respective melodies in the right and left hand were exquisitely molded against a glittering ripple of sixteenths in the upper broken chords that was fairly ravishing to the ear. But it was in the Finale that Mr. Schnabel reached his zenith on this occasion. It would be impossible to overstate his wizardy in this movement, where most pianists flounder hopelessly in a morass of flying notes meaning nothing. Mr. Schnabel, in his re-editing of this division of the work, has at last thrown some real light on its meaning. And what a joy it was to have it performed so that the elaborate figuration that binds the movements together took on shape and proportion under the pianist’s knowing fingers, whence it emerged as a coruscating bit of bravura of the highest type. There is no space to go into a discussion of Mr. Schnabel’s rendition of the Opus 111, which was emphatically dramatic in the first movement and strikingly original in certain phases of the last. In the Arietta, the theme was stated with the singing tone, the tenderness and simplicity it demands and seldom receives. But especially admirable were the mysterious atmosphere created in the fourth variation and the ineffable delicacy of the purling figures of the fifth variant. By art of this superlative nature the pianist completed his splendid tribute to Beethoven’s genius.’

____________

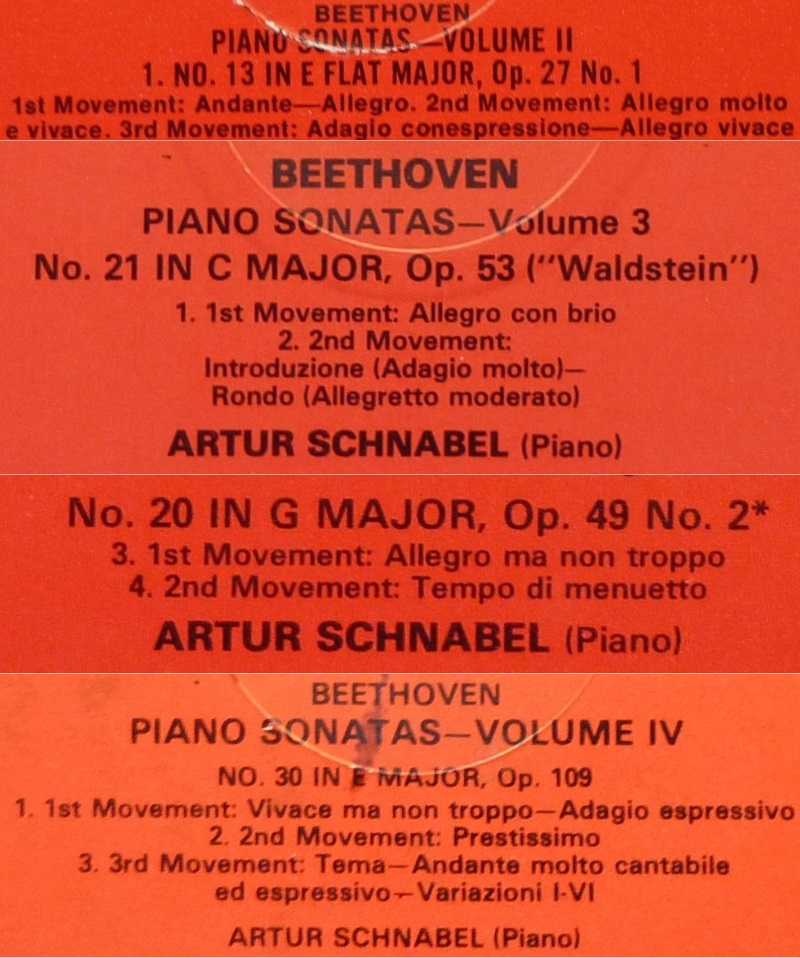

Sonate n°13 Op.27 n°1: 1 Novembre 1932

Sonate n°21 Op.53: 25 Avril & 7 Mai 1934

Sonate n°20 Op.49 n°2: 12 Avril 1933

Sonate n°30 Op.109: 7 Mai 1932

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Schnabel London 1932

Le sixième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel était beaucoup plus court (68′) que le précédent (100′), mais il proposait une très grande Sonate (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) à la fin de chaque partie. La Sonate n°21 Op.53 est la dernière œuvre qu’il a jouée en public (concert du 20 janvier 1951 au Hunter College de New York).

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Une des caractéristiques du jeu de Schnabel, qui n’a pas été soulignée par les critiques new-yorkais, mais que l’on perçoit très bien sur ces reports, est la beauté des pianissimi, remarquables aussi bien par la qualité du timbre que par leur densité de son.

Pour le sixième récital, donné le 19 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarque que Schnabel a bien rendu le caractère enchanteur et romantique de la sonate en si bémol majeur (n°13 Op.27 n°1) et a joué la modeste sonate en sol majeur (n°20 Op.49 n°2) avec la légèreté et le charme qui conviennent à son expression sans apprêt. ‘Mais, c’est avec les deux autres sonates que Mr. Schnabel était confronté au plus grand Beethoven, et c’est dans celles-ci que ses interprétations avaient l’incandescence et la profondeur dignes du compositeur. Le mouvement qui ouvre la sonate en do majeur (n°21 Op.53) était pris un peu plus rapidement que la plupart des pianistes. La puissance et le joie de vivre de la musique justifient cete option, dans la mesure où une allure impétueuse ne mène pas à rendre confus les passages vertigineux. Ceux-ci, sous les doigts de Mr. Schnabel, n’étaient pas confus. Plus encore, la musique était présentée avec une clarté cristalline, avec des nuances délicates et aucun manque d’enthousiasme et de propulsion. L’Adagio était angoissé dans sa réserve, et le dernier mouvement, comme le premier, était un tour de force d’animation et de lyrisme. Si le Beethoven de la ‘Waldstein’ était communiqué avec tout le brio et l’audace de sa robuste maturité, que dire alors du jeu de Mr. Schnabel dans la sonate en mi majeur (n°30 Op.109), musique dans laquelle Beethoven a atteint une incomparable liberté d’imagination? C’était une interprétation d’une portée incandescente, avec le noble Andante rendu avec émotion. Alors que Mr. Schnabel était arrivé au terme des dernières pages apocalyptiques avec leur mélange de sérénité et de tristesse, l’auditoire est resté silencieux. Il a fallu un moment pour rompre la magie. Et alors Mr. Schnabel reçut un tonnerre d’applaudissements, comme à la fin de la ‘Waldstein’, et comme ça a été également le cas tout au long de ce remarquable marathon.’

The sixth program of Artur Schnabel’s complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas was much shorter (68′) than the preceding one (100′), but it offered a very great Sonata (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) at the end of each part. The Sonata n°21 Op.53 is the last work he performed in public (concert of 20 January 1951 at Hunter College in New York).

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

One of the highlights of Schnabel’s playing, not underlined by the New-York critics, but well reproduced on these transfers, is the beauty of the pianissimi, outstanding as to the quality of the timbre as well as to their density of sound.

For the sixth recital given on 19 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarks that Schnabel captured the enchanting, romantic spirit of the E flat major sonata (n°13 Op.27 n°1) and played the unpretentious G major sonata (n°20 Op.49 n°2) with the lightness and charm that its unashamed sentiment required. ‘But it was in the other two sonatas that Mr. Schnabel had the greater Beethoven to contend with, and it was in these that his interpretations had the incandescence and penetration that where worthy of the composer. The opening movement of the C major sonata (n°21 Op.53) was taken a shade faster than the tempi of many pianists. The power and exhilaration of the music justify this procedure, provided a headlong pace does not cause the vertiginous passages to be blurred. They were not blurred under Mr. Schnabel’s hands. More, the music was set forth with crystalline clarity, with delicate nuance and with no loss of fire or propulsion. The Adagio was anguished in its restraint, and the last movement, like the first, was a tour de force of animation and lyricism. If the Beethoven of the ‘Waldstein’ was communicated with all the gusto and daring of his robust maturity, what is there to say of Mr. Schnabel’s playing of the E major sonata (n°30 Op.109), music in which Beethoven had achieved incomparable freedom of the imagination? It was an interpretation of glowing comprehension, with the noble Andante movingly communicated. As Mr. Schnabel concluded the final apocalyptic pages with their intermingling of serenity and sorrow, the audience remained hushed. It was several moments before the spell was broken. Then, Mr. Schnabel was thunderously applauded, as he was at the end of the ‘Waldstein’, and as he has been throughout this remarkable marathon’.

Extrait du programme du Concert/ From Concert program: Schnabel BBC SO/A. Boult Queen’s Hall 15 February 1933