Auteur/autrice : C&A HD

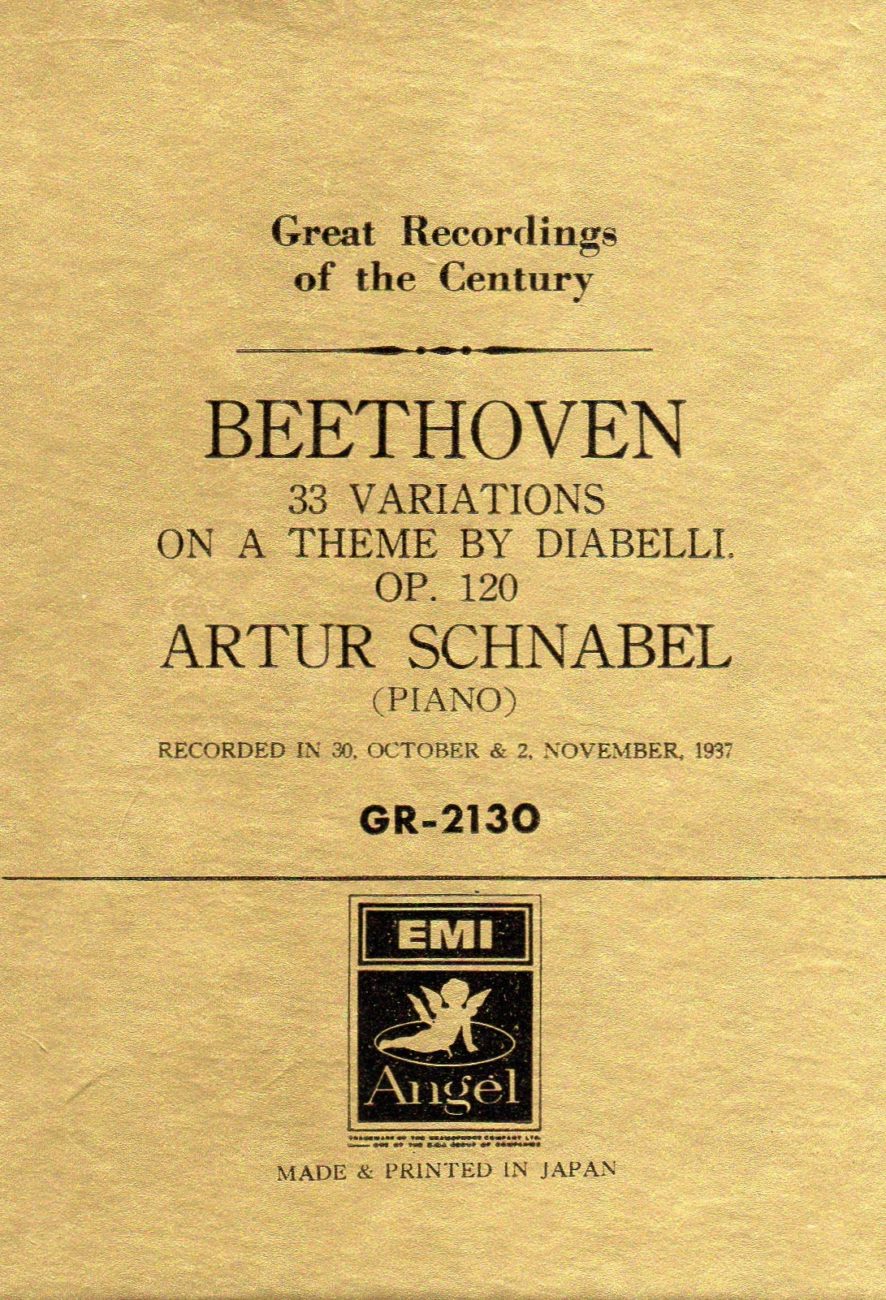

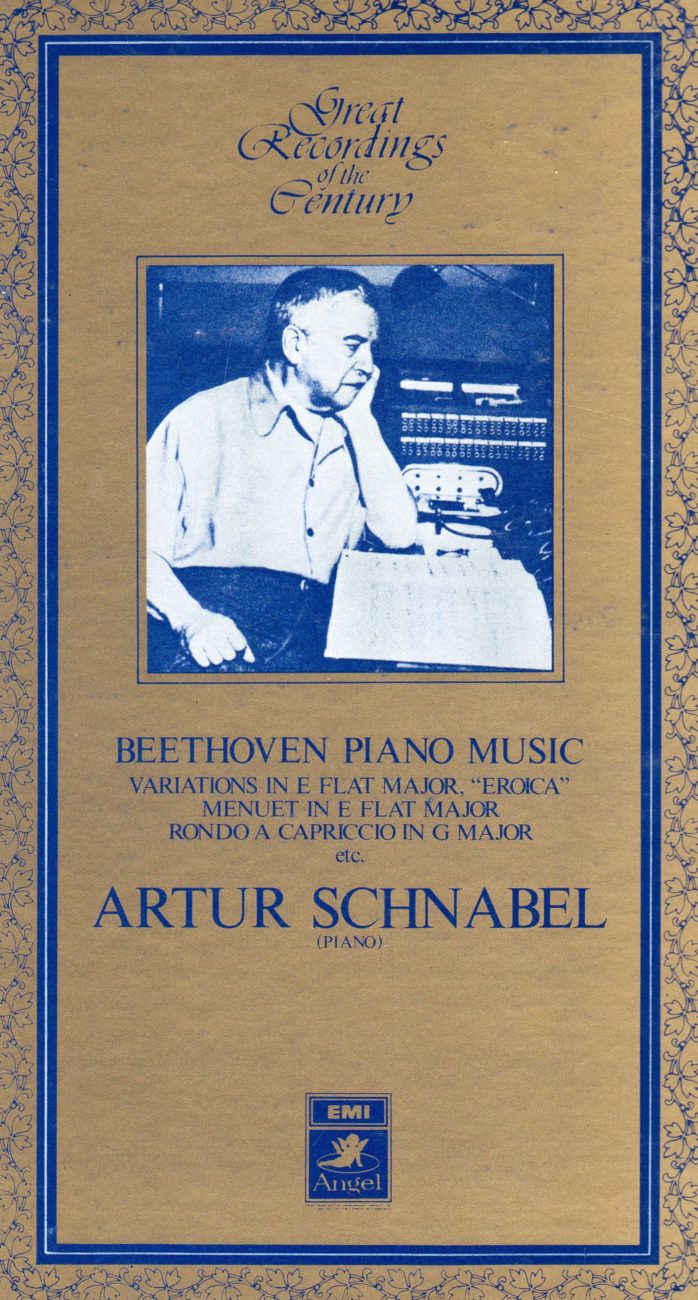

Artur Schnabel, piano Bechstein – London Abbey Road Studio n°3

Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 October 30 & November 2, 1937 (Bechstein n°560)

Variations « Eroïca » Op.35 – November, 9 1938

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Les deux microsillons EMI-Toshiba qui ont servi à cette ré-édition proviennent de reports effectués par Anthony Griffith. Réalisés à partir de pressages vinyles des matrices 78t. d’origine, ils présentent la particularité d’être peu ou pas filtrés et ainsi de nous offrir toute la palette sonore du pianiste, car la technique d’Artur Schnabel, souvent critiquée par ailleurs à cause de ses fausses notes, comportait une gamme très étendue de nuances et de gradations de toucher, de la douceur à la puissance.

La richesse d’écriture de ces variations de Beethoven permet fort heureusement à Schnabel de déployer tout l’éventail de ses qualités pianistiques.

Au cours d’une série de conférences données en 1945 à l’Université de Chicago, Schnabel a eu l’occasion, en réponse à des questions posées posées par les étudiants, d’expliquer quelle avait été sa conception du choix des pianos et de la production du son avant qu’il ne se décide à passer du Bechstein au Steinway à son arrivée aux États-Unis en 1939:

« Je dirais que la qualité qui distingue le piano de tous les autres instruments, est sa neutralité. Sur un piano, un son unique ne peut être beau; c’est la combinaison et la proportion des sons qui apporte la beauté.

Il est nécessaire de produire au moins deux ou trois sons pour donner une impression de sensualité ou pour donner à l’oreille une sensation de musique, alors que presque tous les autres instruments (sauf les instruments à percussion) ou la voix peuvent vous donner un plaisir des sens même avec un seul son. Autour de 1910, on trouvait très ‘moderne’ de dire que le piano était un instrument à percussion et que vous pouviez tout jouer staccato. Stravinsky a beaucoup fait pour la promotion de ces idées de même que de nombreux professeurs de piano, et il y avait même un livre sur ce sujet.

Une fois, un musicien m’a dit – je croyais qu’il plaisantait- que frapper le clavier avec le bout d’un parapluie ou avec le doigt ne faisait pas la moindre différence quant à la sonorité produite. C’était aussi imprimé dans ce livre – et ce n’était pas non plus une plaisanterie. Bien sûr, ça n’a aucun sens, car quiconque veut faire de la musique sait très bien tout ce qu’il peut faire avec les doigts sur le piano.

Il peut produire toutes sortes de sons: pas seulement plus ou moins forts, ou plus ou moins longs, mais aussi différentes qualités. Sur un piano, il est possible d’imiter, par exemple, le son d’un hautbois, d’un violoncelle ou d’un cor. Mais il n’est pas possible d’imiter le son d’un hautbois sur une flûte, ou d’une clarinette sur un violon; ces autres instruments conservent toujours leurs caractéristiques propres. C’est pour ça que je dis que la particularité du piano est, dans son essence, d’être le plus neutre des instruments.

Le piano Bechstein satisfaisait mieux à cette exigence de neutralité que n’importe quel autre piano que j’ai connu. Vous pouviez pratiquement tout faire sur ce piano. Le Steinway – ou plutôt le Steinway d’il y a vingt ans, car il a pas mal changé depuis – était un piano qui voulait toujours montrer quelque chose. Vous voyez, il avait beaucoup trop de personnalité propre.

Au début, quand je voulais produire quelque chose comme, disons, la voix d’un oiseau sur un Steinway, le piano sonnait toujours pour moi comme la voix d’un ténor au lieu d’un oiseau. Pendant de nombreuses années, j’ai eu le sentiment que le piano Steinway ne m’aimait pas. Une idée absurde, mais j’avais ce sentiment. Le piano Bechstein me permettait de produire des effets qui n’étaient pas possibles sur un Steinway. Le son du Steinway vibrait beaucoup plus: il a un double actionnement. Quand vous pressez très légèrement et lentement la touche d’un Steinway, elle s’arrête avant le bas, et elle a besoin d’une certaine pression, d’une seconde pression pour achever sa course vers le bas. Maintenant, j’y suis tellement habitué que cela ne m’irrite plus du tout. Au début, cependant, cela me gênait énormément: en effet, pour produire un fortissimo, vous pouvez jouer légèrement, mais si vous voulez jouer pianissimo, vous avez besoin d’utiliser beaucoup de poids sinon la touche ne descend pas. Cela semble assurément pervers. »

Both EMI-Toshiba LPs used for this re-issue come from transfers made by Anthony Griffith. Dubbed from vinyl pressings of the 78rpm metal parts, they have the particularity of having been unfiltered, or very little, and thus to offer all the pianist’s sound palette, since Artur Schnabel’s technique, otherwise often criticized because of his wrong notes, was comprised of a very extended range of nuances and touch, from softness to power.

The richness of writing of these variations by Beethoven happily allows Schnabel to show the whole spectrum of his pianistic qualities.

During a series of conferences given in 1945 at the University of Chicago, Schnabel, answering questions asked by students, had the opportunity of explaining what had been his views on the choice of pianos and on the production of sound before he decided to switch from Bechstein to Steinway when he arrived in the U-S in 1939:

« I would say that the quality which distinguishes the piano from all other instruments, is its neutrality. On a piano a single tone cannot be beautiful; it is the combination and proportion of tones which bring beauty.

You are forced to produce at least two or three tones in order to create a sensuous impression or to give a sensation of music to the ear, while almost all other instruments (except percussion instruments) or the voice can give you a sensuous pleasure even from a single tone. Around 1910 it was considered very ‘modern’ to say that the piano is a percussion instrument and that you could play everything staccato. Stravinsky did much towards promoting these ideas along with many piano teachers, and there was a book on the subject.

Once I was told by a musician—I hope he was joking—that it does not make the slightest difference for the sonority whether you strike or hit the keyboard with the tip of an umbrella or with a finger. That was also printed in that book—and not as a joke. Of course it is sheer nonsense, for everybody who wants music knows very well all that he can do with the fingers on the piano.

He can produce all kinds of tones: not only louder or softer, shorter or longer tones, but also different qualities. It is possible on a piano to imitate, for instance, the sound of an oboe, a ‘cello’, a French horn. But it is not possible to imitate the sound of an oboe on a flute, or a clarinet on a violin; these other instruments always retain their own characteristics. That is why I said that the distinction of the piano is in its being the most neutral instrument.

The Bechstein piano fulfilled this demand for neutrality better than any other piano I have known. You could do almost anything on that piano. The Steinway—or rather the Steinway of twenty years ago, for it has changed somewhat since that time—was a piano which always wanted to show something. You see, it had much too much of a personality of its own.

At first, when I wanted to produce something like, let me say, the voice of a bird on a Steinway, the piano always sounded to me like the voice of a tenor instead of a bird. For many years, I had the feeling that the Steinway piano did not like me. An absurd idea, but I had that feeling. The Bechstein piano enabled me to show effects not possible on a Steinway. The tone of the Steinway vibrated much more: it has a different action. When you push a Steinway key very lightly and slowly down, it will stop before it has reached the bottom and requires a certain pressure, a second pressure to go down all the way. This is the »double action ». By now I am so used to it that it hardly irritates me any more. At first, however, it disturbed me greatly: for in order to produce a « fortissimo » you can play lightly, but whenever you want to play « pianissimo » you have to use a great deal of weight as otherwise the key would not go down. It certainly seems perverse.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

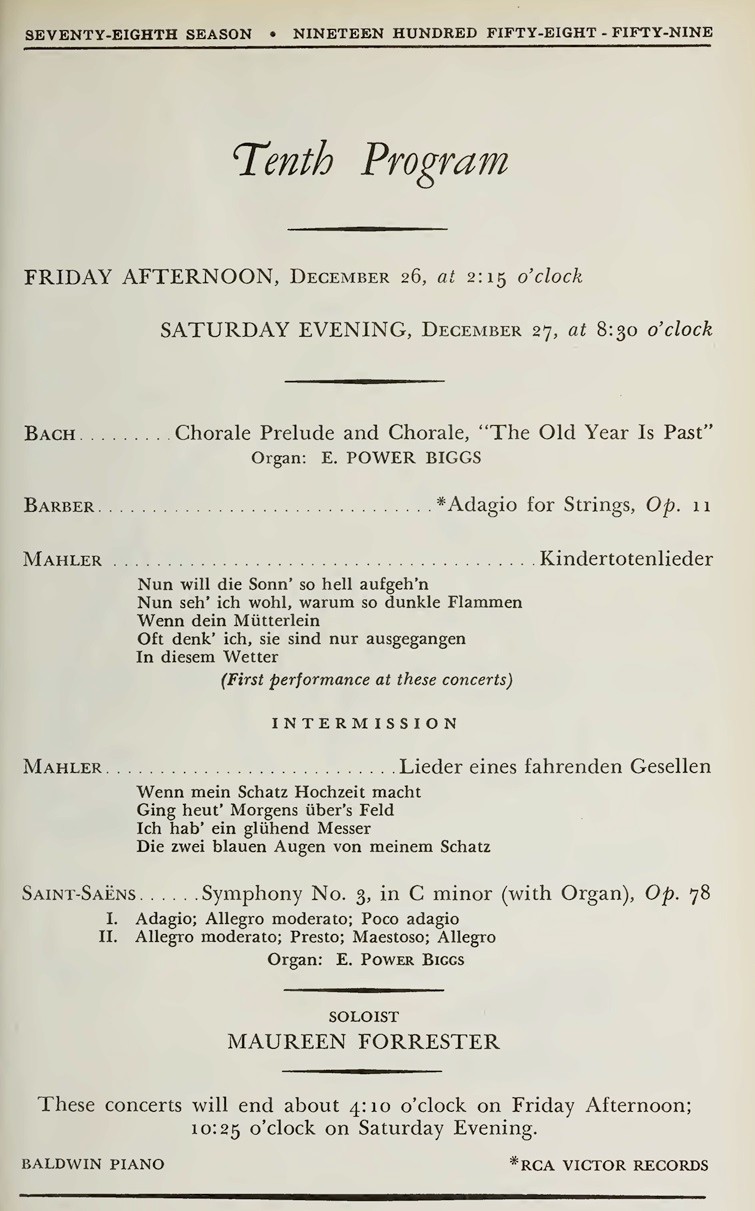

Maureen Forrester, contralto

Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch

Boston Symphony Hall – December 27 1958

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Les enregistrements de Maureen Forrester sont des joyaux de la discographie mahlérienne. On ne ne connait pas la raison du choix de Charles Munch pour diriger ces œuvres, car c’est quasiment la seule fois où, avec le BSO, il a abordé ce compositeur. Le fait est que le disque commercial qui en est résulté est réussi, tant du point de vue du chant que de la direction.

C’est la première fois que les Kindertotenlieder sont donnés par le BSO dans le cadre des concerts d’abonnements à Boston. Auparavant, Marcia Davenport les avait chantés en 1944 avec des membres du BSO sous la direction de Bernard Zighera, et en 1949 le Festival de Tanglewood les avait programmés avec Helen Spaet sous la direction d’Howard Shanet.

Mahler avait été précédemment beaucoup plus joué à Boston qu’on ne le pense:

Symphonie n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphonie n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphonie n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphonie n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphonie n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphonie n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky n’était pas du tout répertorié comme chef mahlérien, et après lui, la direction des œuvres de Mahler a été, au cours des années cinquante, surtout confiée à Richard Burgin, le « concert-master » de l’orchestre (notamment les Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen en 1952), plutôt qu’à des chefs invités.

Le concert du 27 décembre 1958 est la plus ancienne archive conservée en stéréo du BSO en public. L’interprétation en concert se caractérise par une très grande écoute réciproque entre la soliste et les membres de l’orchestre que le chef laisse heureusement se développer. Rappelons que Munch a été pendant plusieurs années un des violons solo du Gewandhausorchester de Leipzig, qui était surtout l’orchestre de l’Opéra, et qu’en cette qualité, il avait acquis une grande expérience de l’accompagnement des solistes.

Le choix du reste du programme n’était pas particulièrement heureux. Pour terminer, Munch s’était en effet livré dans la Symphonie n°3 de Saint-Saëns à une des prestations spectaculaires qu’il affectionnait, ici relativement bien mise en place, et qui lui ont valu à la fois beaucoup de succès et beaucoup de critiques.

Maureen Forrester’s recordings are jewels of the Mahler discography. It is not known why Charles Munch was chosen to conduct these works, since it is the only time he conducted them, and almost the only time he conducted this composer with the BSO. Anyway, the commercial recording that came out of it was successful, for the singing as well as the conducting.

It was the first time that the Kindertotenlieder were performed at the BSO abonnement concerts. Earlier, Marcia Davenport sang them in 1944 with members of the BSO conducted by Bernard Zighera, and in 1949 they were performed at the Tanglewood Festival by Helen Spaet and conducted by Howard Shanet.

In Boston, Mahler was previously performed more than one thinks:

Symphony n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphony n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphony n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphony n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphony n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphony n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky did not have a reputation as a Mahler conductor, and after him, during the 50’s his works were mostly conducted by Richard Burgin, the orchestra « concert-master » (a.o. the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen in 1952), rather than by invited conductors.

The December 27, 1958 concert is the oldest stereo archive from the BSO live. The public performance shows a quite great mutual hearing between the soloist and the orchestra members which the conductor lets develop freely. For several years, Munch was one of the « Konzertmeister » of the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, mainly performing at the Opera, and he then acquired a great experience with the accompaniment of singers.

The remainder of the program was not particularly well chosen. To end the concert, Munch delivered in Saint-Saëns’ Symphony n°3 one of the spectacular performances he was fond of, rather well in place, of a type that owned him plenty of successes as well as criticisms.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

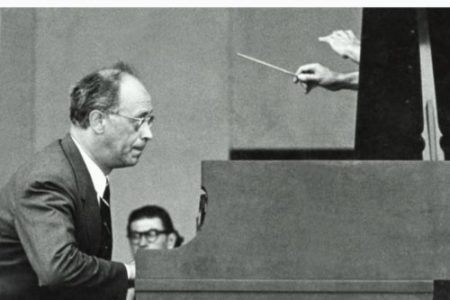

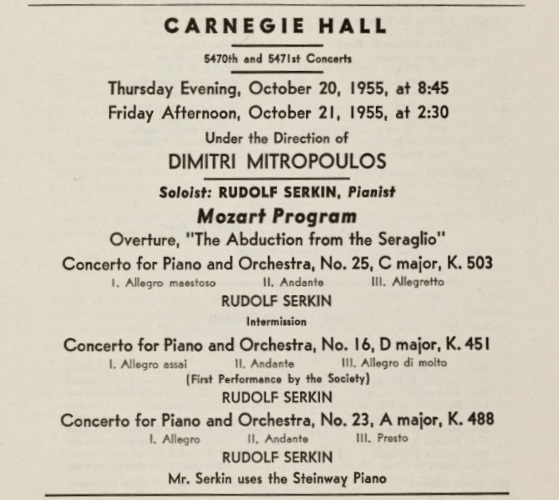

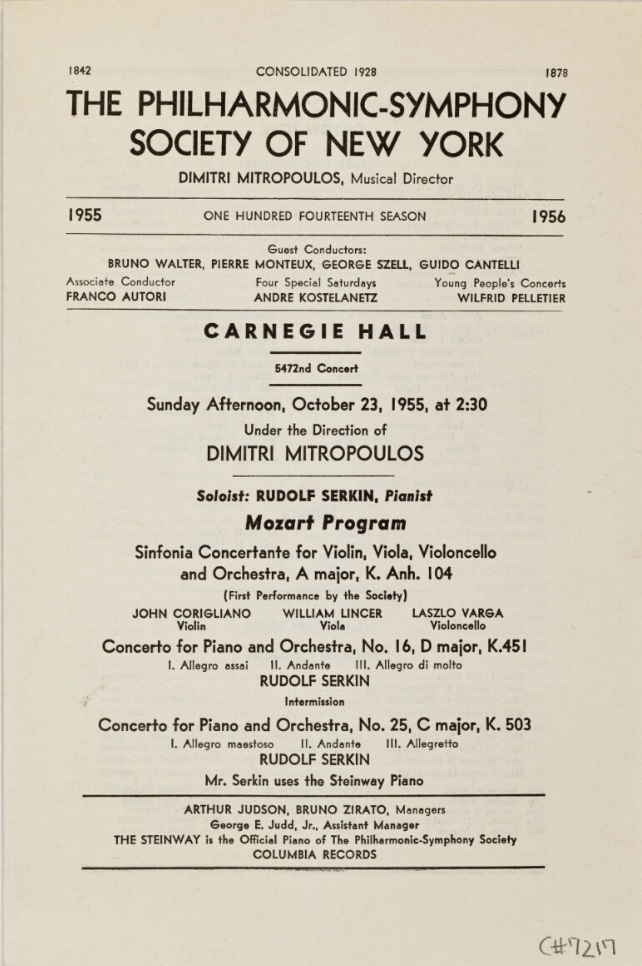

Rudolf Serkin – Dimitri Mitropoulos NYPO

Carnegie Hall – October 23, 1955

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Pour les concerts de gala (avec de nombreux invités) fêtant la rentrée de l’orchestre après une longue tournée européenne (3 septembre – 7 octobre 1955), Rudolf Serkin et Dimitri Mitropoulos ont joué les 20 & 21 octobre 1955 trois Concertos de Mozart, successivement le n°25 K.503, le n°16 K.451 donné pour la première fois avec le NYPO, et le n°23 K.488. Les critiques ont été éminemment favorables, mais plusieurs ont remarqué que, si, quand le pianiste jouait, l’orchestre était réduit à de justes proportions mozartiennes, par contre, l’orchestre seul jouait avec le plein effectif de cordes, engendrant dans les tutti lourdeurs, problèmes d’équilibre et excès de dynamique.

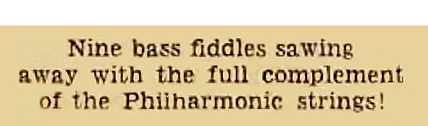

Le plein effectif des cordes avec ses neuf contrebasses! (P-H Lang N-Y Herald Tribune Oct.21,1955)

Des critiques ont souligné que, pour un tel concert d’ouverture, le chef n’aurait pas pu faire autrement qu’employer ce plein effectif.

Le programme du concert radiodiffusé du dimanche 23 ne retenait que les Concertos n°16 & 25, mais s’ouvrait par la Sinfonia Concertante « K. Anh.104 » de Mozart:

Sunday Afternoon Broadcast with only two Concertos played by Rudolf Serkin

For the gala opening concerts (with many guests) to celebrate the orchestra after its long European tour (September 3 – October 7, 1955), Rudolf Serkin and Dimitri Mitropoulos performed three Concertos by Mozart on October 1955, 20 & 21, successively n°25 K.503, n°16 K.451 (first performance with the NYPO), and n°23 K.488. The critics were quite favourable, but several of them remarked that, if in solo passages, the orchestra had the size of a Mozart ensemble, however the orchestra alone performed with a full complement of strings, thus with problems of heaviness, balance shifts and excessive dynamics in tutti. Critics underlined that, for such an opening concert, the conductor could not do otherwise than to display the full body of strings. Of these, only Concertos n°16 K.451 and n°25 K.503 were played at the Sunday Afternoon Broadcast concert, which opened with Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante « K. Anh.104 ».

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

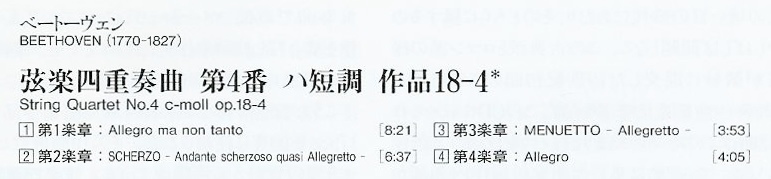

n°4 Op.18 n°4 – Moscou Petite Salle du Conservatoire 13 mars 1960 Cycle Beethoven 3ème concert

n° 10 Op.74 – Moscou Petite Salle du Conservatoire 13 avril 1960 Cycle Beethoven 4ème concert

n°16 Op.135 – studio 12 juin 1952

Dmitry Tsyganov, violon I, Vassily Shirinsky, violon II, Vadim Borisovsky, alto et Sergei Shirinsky, violoncelle

Au cours de la saison 1959-1960, le Quatuor Beethoven a donné dans la Petite Salle du Conservatoire de Moscou un cycle de quatre concerts dédiés à des Quatuors de Beethoven, à savoir le 31 octobre 1959 (concert I) Quatuors n°1 Op.18 n°1 et n°7 Op.59 n°1; le 13 décembre 1959 (concert II) Quatuors n°2 Op.18 n°2 et n°15 Op.132; le 13 mars 1960 (concert III) Quatuors n°4 Op.18 n°4 et n°14 Op.131 et enfin le 13 avril 1960 (concert IV) Quatuors n°10 Op.74 et n°13 Op.130. De ces concerts, ont subsisté des enregistrements des Quatuors n°4 Op.18 n°4 et n°10 Op.74. Ils ont été publiés au Japon en 1995 dans un coffret Triton de 7 CD (MECC 26-018-26024) qui est devenu introuvable et ces enregistrements ne sont pas accessibles autrement. Ils nous permettent d’écouter le Quatuor Beethoven jouer Beethoven en concert dans sa formation d’origine.

Dmitry Tsyganov était célèbre pour son interprétation dionysiaque voire diabolique du vigoureux et virtuose passage en arpèges du premier violon qui intervient peu avant la coda du premier mouvement du Quatuor n°10 Op.74 dit « Les Harpes ». Cet enregistrement permet de fixer ce moment unique, bien mieux que la version de studio qui date de 1972.

L’enregistrement du Quatuor n°16 Op.135 provient d’un autre CD, publié en France en 1991 par la firme Vogue (VG 651027). Il s’avère en tous points supérieur au microsillon Melodiya D8023-8024 publié en 1961, dans lequel l’ajout d’une réverbération excessive donnait une apparente plus-value sonore, mais dénaturait l’interprétation.

Il existe dans plusieurs Radios allemandes (Köln, Frankfurt, Bayerische Rundfunk) ainsi qu’à la Radio de Kiev d’autres enregistrements du Quatuor Beethoven dans sa formation d’origine. Espérons que ceci intéressera un éditeur. On peut penser notamment à Meloclassic qui a publié beaucoup d’archives, en particulier de musique de chambre, provenant de Radios allemandes.

________________

During the 1959-1960 season, the Beethoven Quartet gave in the Small Hall of the Moscow Conservatory a cycle of four concerts comprised of Quartets by Beethoven, namely on October 31, 1959 (concert I) Quartets n°1 Op.18 n°1 and n°7 Op.59 n°1; on December 13, 1959 (concert II) Quartets n°2 Op.18 n°2 and n°15 Op.132; on March 13, 1960 (concert III) Quartets n°4 Op.18 n°4 and n°14 Op.131 and to end with, on April 13, 1960 (concert IV) Quartets n°10 Op.74 and n°13 Op.130. From these concerts, recordings of Quartets n°4 Op.18 n°4 and n°10 Op.74 have survived. They have been published in Japan in 1995 in a « Triton » 7 CD boxset (MECC 26-018-26024) that is long out of print and these recordings are not available otherwise. They allow us to hear the Beethoven Quartet play Beethoven live with their four original members.

Dmitry Tsyganov was famous for his dionysiac and almost diabolical performances of the vigourous and virtuoso « arpeggio » sequence of the first violon which comes shortly before the coda of the first movement of Quartet n°10 Op.74 « Harp ». This recording allows to perpetuate this unique moment, much better than the 1972 studio version.

The recording of Quartet n°16 Op.135 comes from another CD, published in France in 1991 by Vogue (VG 651027). It is vastly superior to the Melodiya LP D8023-8024, published in 1961, in which an excess of added reverb gave a flattering sound but almost fatally marred the performance.

In several German Radios (Köln, Frankfurt, Bayerische Rundfunk) as well as the Kiev Radio, there exist other recordings of the Beethoven Quartet with its four original members. Let’s hope a record company will be interested, e.g. Meloclassic which published many archive recordings, a.o. of chamber music, from German Radios.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

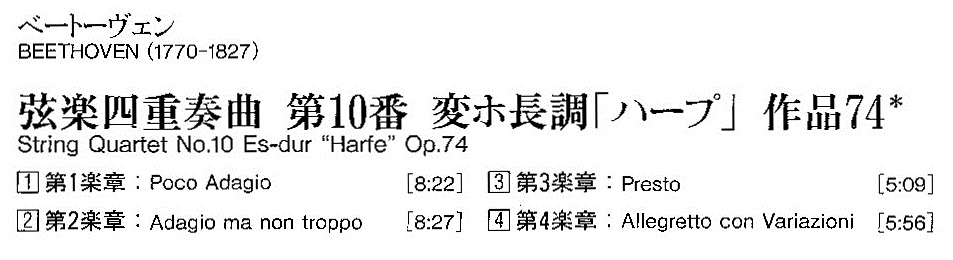

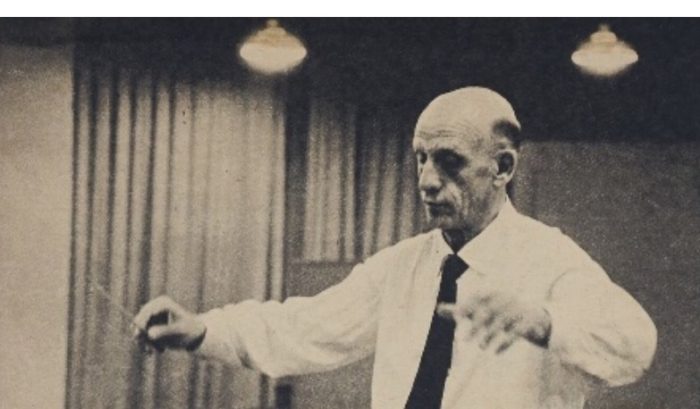

Dimitri Mitropoulos New York Philharmonic

Columbia 30th Street Studios – 24 février 1957

Bande 19 cm/s 2 pistes (7.5 ips ; 2 tracks) OMB – 6

Nous poursuivons cet Hommage à Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960) à l’occasion du 125ème anniversaire de sa naissance. D’ici la fin de l’année, quatre autres publications vont suivre.

Février 1957, c’était pour Columbia le début de la stéréo. Le 18 février Bruno Walter commença à Carnegie Hall l’enregistrement de la Deuxième Symphonie de Mahler qu’il ne pourra terminer que l’année suivante. Pour cette Symphonie Fantastique, nous sommes dans les Studios Columbia de la 30ème rue, une ancienne église arménienne, qui a été utilisée depuis fin 1948 pour un très grand nombre d’enregistrements de musique de chambre et d’orchestre. La prise de son stéréophonique, très soignée, assume une esthétique sonore qui vise au spectaculaire, ce qui fonctionne parfaitement avec cette œuvre. L’interprétation, comme toujours très personnelle, de Mitropoulos est une réussite. Notons que le chef l’avait donnée au concert à Carnegie Hall les jeudi 21 et vendredi 22 février, et l’enregistrement a été réalisé le dimanche 24.

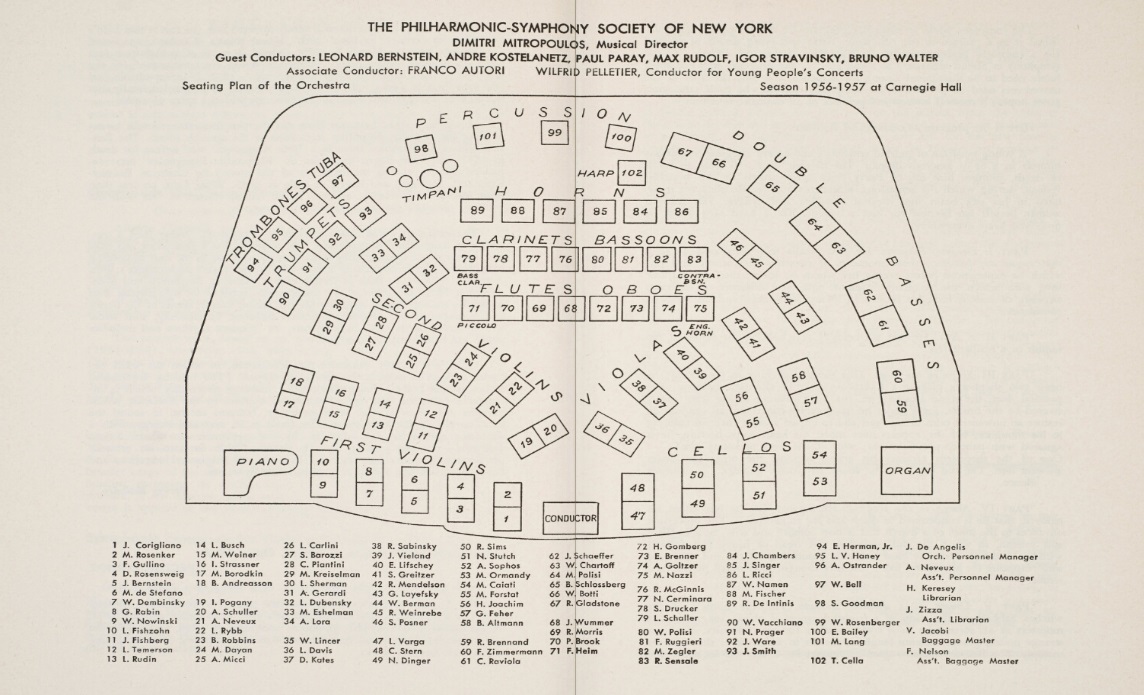

Disposition de l’orchestre à Carnegie Hall (saison 1956-1957)

We go on with this Tribute to Dimitri Mitropoulos (1896-1960) for the 125th Anniversary of his birth. Until the end of this year, four more posts will follow.

February 1957 was for Columbia the beginning of Stereo. On February 18, Bruno Walter began in Carnegie Hall the recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony which he was able to complete only the following year. For this Symphonie Fantastique, we are in the Columbia 30th Street Studios, a former Armenian church, which was used since the end of 1948 for a very large number of chamber music and orchestral recordings. The stereophonic recording, very carefully done, displays a chosen sound spectacular aesthetics, which matches this work perfectly well. The performance, very personnal, as always with Mitropoulos, is a winner. Note that the conductor performed it at Carnegie Hall on Thursday 21 and Friday 22, and the recording was made on Sunday, the 24th.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.