Auteur/autrice : C&A HD

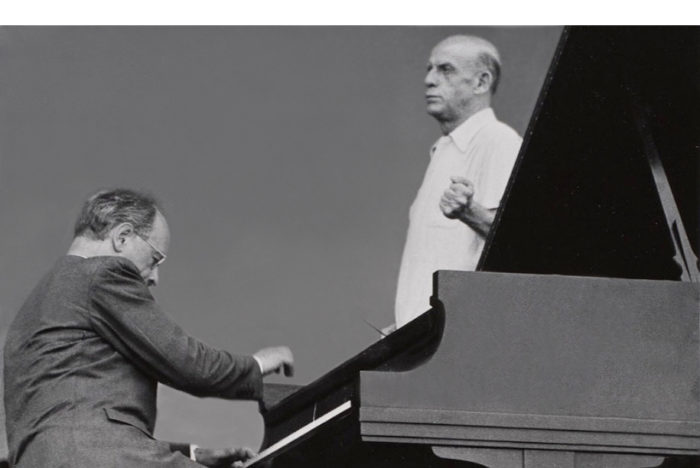

Rudolf Serkin – Dimitri Mitropoulos NYPO

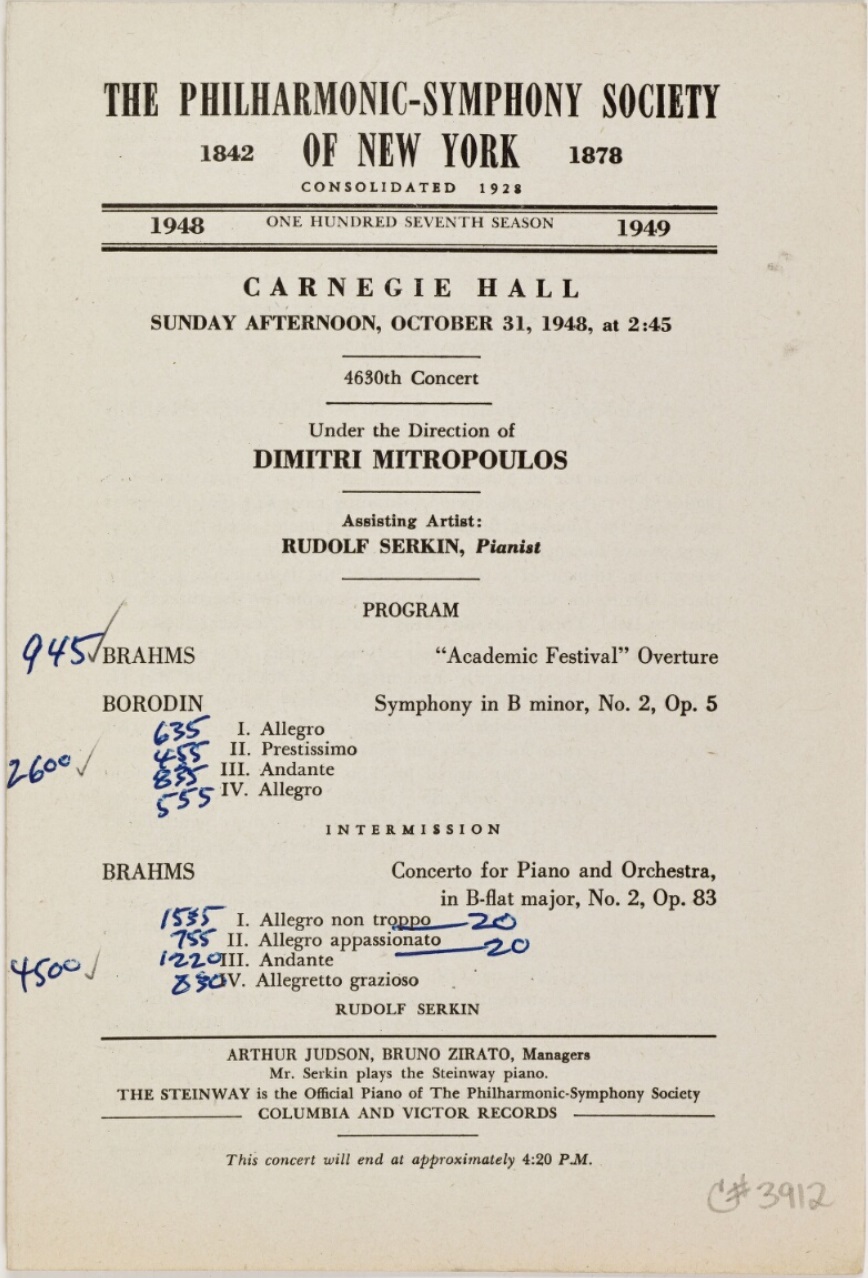

Carnegie Hall – 31 octobre 1948 – Violoncelle solo: Leonard Rose

Source: Bande/Tape 38 cm/s / 15 ips

Entre le Concert du 20 février 1936 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58 & Mozart Concerto n°27 K.595 avec Arturo Toscanini) et le « Rudolf Serkin Golden Jubilee Program » du 20 février 1986 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58 avec Zubin Mehta), Rudolf Serkin a joué plus de 110 fois avec le NYPO, dont 27 Concerts sous la direction de Dimitri Mitropoulos, mais aucun disque avec ce dernier n’en est résulté. Ce rare enregistrement du Concerto n°2 de Brahms représente leur première collaboration avec le NYPO. L’interprétation est d’une rare intensité et il est donc tentant de la comparer avec la célèbre version Edwin Fischer/Wilhelm Furtwängler dont le style est bien sûr très différent.

(Enregistré sur disques 33 tours 40 cm à gravure directe, reportés ensuite sur bande magnétique).

_________________

New York Philharmonic – Concerts avec/with Rudolf Serkin & Dimitri Mitropoulos

(Carnegie Hall sauf indication contraire / Carnegie Hall unless otherwise indicated)

– Oct. 28, 29 & 31, 1948 Brahms Concerto n°2 Op.83

– Jan. 5, 6, 1950 Reger Concerto Op.114

– Jan. 7, 8,1950 Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58

– Nov. 13, 1950 Mozart Rondo K.382; Schumann Introduction & Allegro Op.134 (US Premiere), Mendelssohn Concerto n°1 Op.25; Strauss Burleske.

– Sept. 1, 1951(Edinburgh Usher Hall) Schumann Concerto Op.54

– Nov. 22, 23 & 25, 1951 Brahms Concerto n°1 Op.15

– Jan. 28 & 29, 1954 Mozart Concerto n°17 K.453; Strauss Burleske; Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58

– Febr. 17, 18 & 20, 1955 Brahms Concerto n°2 Op.83

– June 20, 1955 (Lewisohn Stadium – Manhattan) Beethoven Concerto n°5 Op.73

– Oct 20, 21, 1955 Mozart Concerto n°25 K.503, n°16 K.451 & n°23 K.488

– Oct 23, 1955 Mozart Concerto n°16 K.451 & n°25 K.503

– Febr. 28, March 1, 1957 Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58

– Febr. 6, 7 & 9, 1958 Schumann Introduction & Allegro Op.134; Strauss Burleske

– Febr. 8, 1958 Reger Concerto Op.114

(Une date soulignée indique un concert radiodiffusé/ an underlined date indicates a broadcast concert)

_________________

_________________

Between the Concert of February 20, 1936 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58 & Mozart Concerto n°27 K.595 with Arturo Toscanini) and the « Rudolf Serkin Golden Jubilee Program » of February 20, 1986 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58 with Zubin Mehta), Rudolf Serkin performed more than 110 times with the NYPO, including 27 Concerts (listed above) under the direction of Dimitri Mitropoulos, but no commercial recording with the latter ever materialized. This rare recording of Brahms’ Second Concerto n°2 (solo cellist: Leonard Rose) represents their first collaboration with the NYPO. The performance has a rare intensity, and for that matter, it is tempting to compare it with the well-known version with Edwin Fischer and Wilhelm Furtwängler, who of course play in a very different style.

(Recorded on 33rpm 16″ Transcription Discs later dubbed on magnetic tape).

_________________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

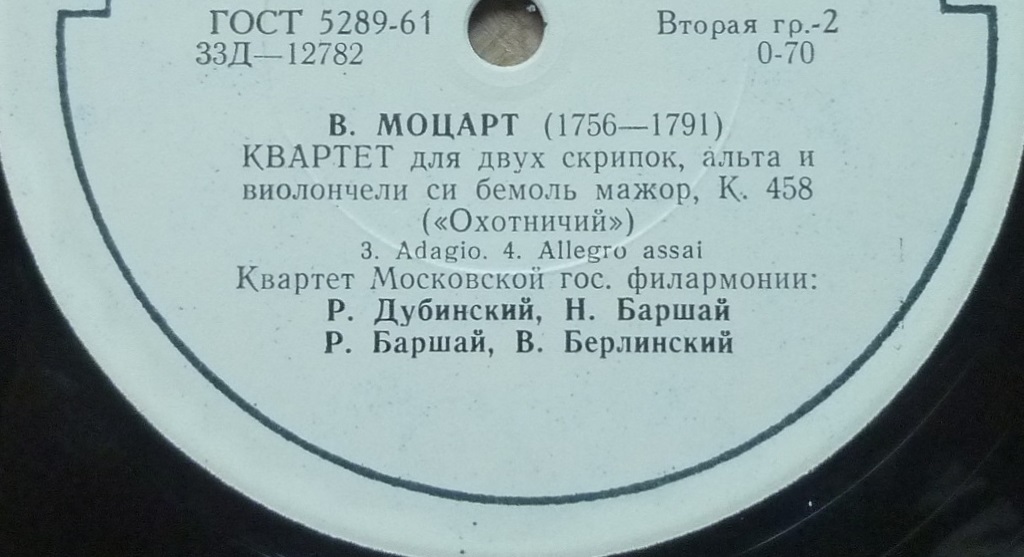

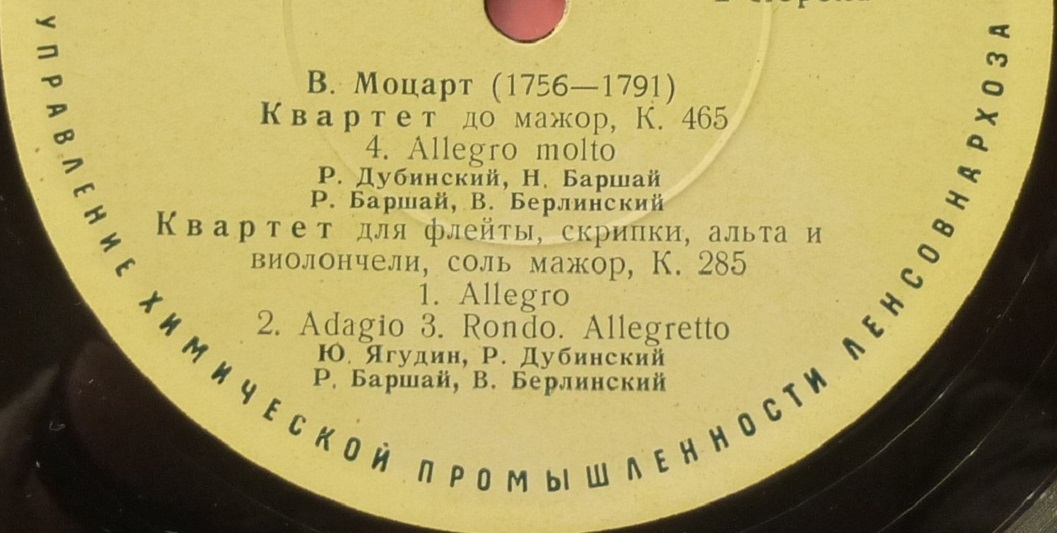

Rostislav Dubinsky , violon I, Nina Barshai violon II (K458 & 465), Rudolf Barshai, alto et Valentin Berlinski, violoncelle.

Yuli Yagudin, flûte (K285)

Enregistré vers 1950

Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou, c’est la dénomination qu’avait adopté entre 1947 et 1955, le futur Quatuor Borodine. Seuls quelques enregistrements, ici reproduits, de quatre œuvres de Mozart avaient fait l’objet d’une publication en 1963 sous forme de microsillons, à l’occasion des vingt ans de la création du Quatuor. Un récent coffret de 20 CD en Hommage à Rudolf Barshaï propose un enregistrement du Quatuor n°1 Op.49 de Chostakovitch (Concert à la Petite Salle du Conservatoire de Moscou – 3 juin 1951).

La chronologie des différentes compositions du Quatuor est relativement complexe, depuis la formation provisoire sous forme de Quatuor d’étudiants (1943), jusqu’à la constitution en 1947 d’un premier ensemble stable (Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou), puis du choix de la dénomination de Quatuor Borodine en 1955 (source: Valentin Berlinsky – A Quartet for Life publié par Kahn & Averill London; Le Quatuor d’une Vie – Aedam Musicae). Si on met de côté la participation « anecdotique » de Rostropovitch en 1943, le cœur du Quatuor, ce sont Rostislav Dubinsky et Valentin Berlinsky. On notera que le remplacement de R. Dubinsky par Levon Sachs (1944-1945), le violon solo de l’orchestre du Théâtre Bolshoï, est dû au fait que Dubinsky s’est rendu à Minsk récemment libéré pour être pendant un an le violon I du Quatuor de Biélorussie.

__________________________

Le Quatuor Borodine au fil du temps/The Borodin Quartet in the course of time

I – Quatuor d’étudiants du Conservatoire de Moscou / Student Quartet at the Moscow Conservatory (1943-1947)

II – Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou / Moscow Philharmonic Quartet (1947-1955)

III – Quatuor Borodine / Borodin Quartet (depuis/since 1955)

Violon/Violin I

Rostislav Dubinsky: 1943-1944: Levon Sachs: 1944-1945; Rostislav Dubinsky: 1945-1976, Mikhail Kopelman: 1976-1996; Ruben Aharonian: depuis/since 1996

Violon/Violin II

Pavel Granovsky (1943), Grigory Kemlin: 1943-1945; Vladimir Rabei: 1945-1947; Nina Barshai: 1947-1952; Yaroslav Alexandrov: 1952-1974; Andrei Abramenkov: 1974-2011

Alto/Viola

Yuri Nikolayevsky: 1943-1944; Rudolf Barshai: 1944-1953; Dmitri Shebalin: 1953-1996; Igor Naidin: depuis/since 1996

Violoncelle/Cello

Mstislav Rostropovitch: 1943 (deux semaines!/two weeks!); Valentin Berlinsky: 1943-2007; Vladimir Balshin: depuis/since 2007

__________________________

Dans l’ouvrage précité, Valentin Berlinsky relate ce que représentait le Conservatoire de Moscou au cours des années quarante. En voici un extrait :

Le Conservatoire de Moscou était au cours des années 40 une institution exceptionnelle. Le professionnalisme en vigueur chez les personnalités éminentes qui y enseignaient était fabuleux. Le Conservatoire était pour nous un temple de l’art vers lequel nous nous précipitions chaque jour. Il est difficile d’imaginer aujourd’hui qu’en tant qu’étudiants nous partagions les couloirs avec des compositeurs tels que Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Chostakovitch, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Yuri Shaporin, Vissarion Shebalin, et les pianistes Heinrich Neuhaus et Alexander Goldenweiser. Nos professeurs étaient les violinistes David Oïstrakh et Abram Yampolsky, Zeitlin et Mostras, et les violoncellistes Semyon Kozolupov and Sviatoslav Knushevitsky. Les noms les plus éminents, bien que nous n’en ayons pas eu conscience à l’époque. Nous considérions leur présence comme tout à fait normale.

Un style de communication très spécifique de cette période était encore en vigueur. Il se reflétait dans le comportement, l’apparence, et le discours de nos professeurs. Ils s’intéressaient sincèrement à nos carrières futures. La foi qu’ils avaient en nous nous motivait à répondre à leurs attentes et à ne pas les décevoir; nous devions répondre à cet investissement sur notre futur! Les Prix et les récompenses ne devaient jamais être accordés trop tôt. Il se pourrait qu’un artiste n’ait pas besoin de gloire, et la gloire pouvait être nuisible à certains; mais l’artiste a sûrement besoin d’être reconnu. L’artiste doit se sentir nécessaire. Je parle ici des arts classiques, dont la signification et le but ne sont pas en premier lieu le divertissement. C’est comme ça que notre quatuor fonctionnait, et cet exemple le montre. Si nous travaillions les Quatuors de Beethoven, nous allions les jouer à Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus, qui avait une connaissance encyclopédique des œuvres de Beethoven. Nous entrions alors dans sa salle de classe qui n’était jamais vide (il y avait toujours de l’ordre de vingt ou trente personnes dans ses classes).

Et il disait: ‘Ah, vous voici, nous vous attendions. Qu’allez vous jouer aujourd’hui?’

‘ Le Quatuor en do dièse mineur de Beethoven’.’

‘Ah, l’opus 131’, et il se dirigeait vers le piano pour souligner les thèmes principaux sans même s’asseoir. Pour Mozart et Haydn, nous allions voir Alexander Goldenweiser, le grand spécialiste des mélismes. Il disait: ‘Personne à part moi ne sait comment jouer correctement les phrases mélismatiques’. Neuhaus et Goldenweiser, dont nous absorbions l’influence avec reconnaissance, ont été aussi nos partenaires au concert. Il existe toujours un enregistrement du Quatuor avec Goldenweiser – le Quatuor avec Piano de Mozart K493, un vieux disque, un disque noir, vous vous en souvenez? Mais aucun enregistrement de nous avec Neuhaus n’a survécu. Enregistrer des concerts publics n’était pas très courant. Nous avons joué ensemble les Trios de Tchaïkovski et les Quintettes avec Piano de Schumann et de Franck.

A l’époque, nous avons eu d’autres partenaires, des excellents pianistes qui enseignaient au Conservatoire de Moscow: parmi ceux-ci, Yakov Zak, Yakov Flier, Lev Oborin, Maria Veniaminovna Yudina, Grigory Ginzburg et Alexander Jocheles.

Nous avons joué notre programme à Lev Moiseyevich Tseitlin, un merveilleux chambriste et le fondateur du Persimfans, une des expériences orchestrales les plus intéressantes de l’histoire de l’interprétation. Il était toujours surprenant, et son énergie était unique…. Je me souviens bien de nos leçons avec Lev Moiseyevich. Nous avons joué pour lui le Quatuor de Ravel et l’opus 59 no. 2 en mi mineur de Beethoven. Nous avons joué aussi pour Yampolsky, Kozolupov et d’autres encore. Terian était très impliqué dans notre Quatuor, mais nous conseillait (en fait il insistait) pour que nous allions consulter ces autres musiciens. Cette absence de jalousie envers ses étudiants était caractéristique de l’époque. Ce n’est que bien plus tard que j’ai compris ce que cachaient le jalousie et la possessivité envers ses étudiants (ou leur absence). L’aspect psychologique est ici crucial: les jeunes musiciens doivent bien sûr développer leurs propres compétence et leurs propres ressources pour conquérir leur liberté et leur confiance. Terian le savait. Il prenait soin de notre développement artistique. Cette absence de jalousie est une partie de ce qui distingue ces professeurs de ceux de la génération actuelle.

La différence est énorme, et repose sur la réflexion musicale. Notre professeur de quatuor était Yevgeny Mikhailovich Guzikov (N.B. Y. Guzikov 1887-1972 a été le premier professeur russe à mettre au point une méthode pédagogique pour les ensembles de musique de chambre, sur la base du travail effectué avec les Quatuors Komitas, Spendiarov, Glinka et Taneyev). Il ne tolérait pas les tempi ouvertement rapides. Il nous a enseigné que ‘Allegro’ ne signifie pas toujours ‘rapide’. C’est souvent une indication, d’un caractère d’allégresse, notamment dans les œuvres classiques. Il ne fallait pas seulement tenir compte des symboles conventionnels (qui, après tout ne sont que des symboles) mais aussi de la forme de la mélodie, de l’harmonie, et prêter une oreille attentive aux sonorités. Nous devions être capables de lire et d’évaluer la signification de ces symboles. De même, la dynamique est principalement relative à la forme et non aux décibels. Qu’est-ce que ‘forte’ signifie en fait? Avec force et solidité, mais pas nécessairement ‘fort’! C’est comme ça que nous avons appris la rigueur, la minutie et la réflexion. Et quand aucun de ces symboles ne se trouve dans la partition, comme dans les œuvres de Bach? C’est l’occasion de penser au moyen par lequel la musique se développe, aux doigtés, et aux coups d’archet. Des tempi excessivement rapides appauvrissent la musique. Des vitesses plus modérées signifient que la beauté tonale de l’œuvre peut être montrée en détail, de même que l’interaction entre les voix et bien d’autres choses. Guzikov avait de ce fait raison.

Le flûtiste Yuli Yagudin (K285) était un des meilleurs élèves de Vladimir Tsybin (1877-1949), fondateur de l’école russe de flûte.

Moscow Philharmonic Quartet is the name under which the later Borodin Quartet was known between 1947 and 1955. Only a few recordings, posted here, of four works by Mozart have been published as LPs in 1963 for the 20th Anniversary of the birth of the Quartet. A recent 20 CD Album, A tribute to Rudolf Barshaï, offers a recording of Shostakovich’s First Quartet Op.49 (Concert at the Small Hall of the Moscow Conservatory – June 3, 1951).

The chronology of the various line-ups of the Quartet is rather complicated (see above « The Borodin Quartet in the course of time »), since the initial provisional one as a student Quartet (1943), until the creation in 1947 of a first stable ensemble (Moscow Philharmonic Quartet), then of the choice of the name Borodin Quartet in 1955 (source: Valentin Berlinsky – A Quartet for Life published by Kahn & Averill London). If we set aside the « anecdotic » participation of Rostropovitch in 1943, the core of the Quartet, is both Rostislav Dubinsky and Valentin Berlinsky. Note that the replacement of R. Dubinsky by Levon Sachs in 1944-1945, leader of the Bolshoï Theatre Orchestra, is due to Dubinsky’s move to the recently liberated Minsk to lead during a year the Belarusian Quartet.

In the above cited book, Valentin Berlinsky decribes what the Moscou Conservatory of the 1940s meant to him. Here is an excerpt:

The Moscow Conservatory of the 1940s was an exceptional institution. The professionalism among the imposing characters who taught there was outstanding. The Conservatory was, for us, a temple of art to which we hurried each day. It is difficult to imagine today that as students we shared the corridors with composers such as Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Yuri Shaporin, Vissarion Shebalin , and the pianists Heinrich Neuhaus and Alexander Goldenweiser. Our teachers were the violinists David Oistrakh and Abram Yampolsky, Zeitlin and Mostras, and cellists Semyon Kozolupov and Sviatoslav Knushevitsky. Names to conjure with, though we did not realise this at the time. We took their presence completely for granted.

A style of communication that was very specific to this period was still in use. This was reflected in the behaviour, appearance and speech of our teachers. They were sincerely interested in our future careers. The faith they had in us made us eager to meet their expectations and not to disappoint them; we had to provide a return on this investment in our future! Prizes and rewards should never be granted too early. It could be that the artist does not need glory, and glory could be harmful to some; but the artist certainly needs recognition. The artist must feel necessary. I am talking here of the classical arts, the meaning and purpose of which do not primarily involve entertainment. By way of an example, this is how our quartet worked. If we were working on Beethoven’s Quartets, we would play them to Heinrich Gustavovich Neuhaus, who had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the works of Beethoven. We would enter his classroom, which was never empty (there were almost always twenty or thirty people in his classes).

He would say: ‘Ah, there you are, we were waiting for you. What are you going to play today?’

‘Beethoven’s Quartet in C sharp minor.’

‘Ah, opus 131’, and he would go to the piano and pick out the main themes without sitting down. For Mozart and Haydn, we would go to Alexander Goldenweiser, the great specialist in melisma. He would say: ‘Nobody knows how to play melismatic phrases properly apart from me’.

Neuhaus and Goldenweiser, whose influence we absorbed gratefully, also partnered us on the stage. There are still some recordings of the Quartet with Goldenweiser – Mozart’s Piano Quartet K493, an old record, a black one, you remember them? But no recording of us with Neuhaus has survived. Recording concerts live was not a very common practice. We played the Tchaikovsky Trios and the Schumann and Franck Piano Quintets together.

At the time we had other partners, excellent pianists who taught at the Moscow Conservatory: these included Yakov Zak »,Yakov Flier, Lev Oborin, Maria Veniaminovna Yudina, Grigory Ginzburg and Alexander Jocheles.

We also played our programme to Lev Moiseyevich Tseitlin, a wonderful chamber music player and creator of Persimfans, one of the most interesting experiments in the history of orchestral performance. He was always surprising, with a unique energy…. I remember our lessons with Lev Moiseyevich well. We played Ravel’s Quartet and Beethoven’s opus 59 no. 2 in E minor for him. We also played for Yampolsky, Kozolupov and others. Terian was closely involved with our Quartet, but advised (indeed insisted) that we consult these other musicians. This lack of jealousy towards his students was characteristic of the time. I only realised much later what lies behind jealousy and possessiveness (or the lack of it) towards one’s students. The psychological aspect is crucial here: young musicians must naturally increase their own capabilities and resources in order to gain liberty and confidence. Terian knew this. He took care over our artistic development. This lack of jealousy is part of what sets those teachers apart from the current generation.

The difference is huge, and it originates in musical reflection. Our quartet teacher was Yevgeny Mikhailovich Guzikov. (N.B. Y. Guzikov 1887-1972 was the first Russian teacher to set a pedagogical method for chamber ensembles, based on work he had done with the Komitas, Spendiarov, Glinka and Taneyev Quartets). He would not tolerate overly fast tempos. He taught us that ‘Allegro’ does not always mean ‘fast’. It is often an indication, of character, of joyfulness, particularly in classical works. Attention should not just be paid to the conventional symbols (which are, after all, just symbols) but also to the shape of the melody, the harmony, and a careful ear to sonorities. We must be able to read and appreciate the connotations of these symbols. Similarly, dynamics are primarily about shape and not decibels. What does ‘forte’ actually mean? With strength and solidity, not necessarily ‘loud’! This is how we learned rigour, thoroughness and thoughtfulness. What if none of these symbols is contained in the score, as in the works of Bach? This provides an opportunity to think about the way in which the music develops, about fingerings, and about bow strokes. Excessively fast tempos impoverish the music. More moderate speeds mean that the tonal beauty of the work can be shown in detail, along with the interplay of the voices and much more besides. Guzikov was therefore right in his view.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

William Kapell – Dimitri Mitropoulos NYPO

Carnegie Hall – April 12 1953

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

La source utilisée jusqu’à présent pour les rééditions de cet enregistrement présente un spectre de fréquences tronqué dans l’aigu, ce qui se traduit par un son quelque peu étouffé qui empêche d’apprécier la splendeur sonore du piano de William Kapell (1922-1953), et aussi de l’orchestre.

La bande recopiée ici est en tout point supérieure et permet de restituer enfin cette grande interprétation que Kapell a donnée pour sa dernière apparition à New York avec un orchestre.

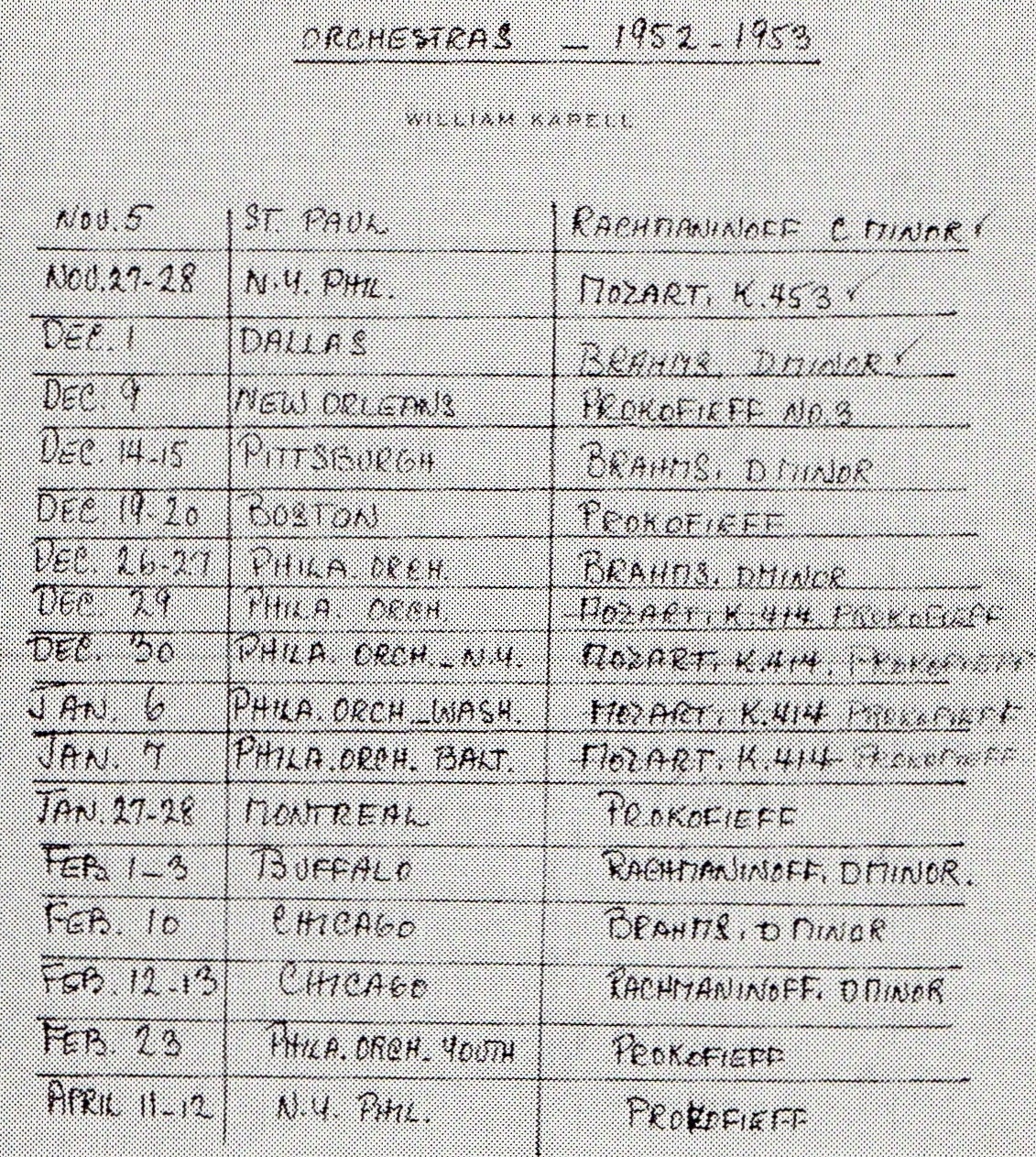

Pour sa dernière saison complète, Kapell a joué à travers les Etats-Unis un ambitieux programme de concertos, avec notamment trois apparitions à New-York, à savoir les 27 et 28 novembre 1952 (avec Dimitri Mitropoulos) pour le Concerto N°17 K. 453 de Mozart qu’il rejouera à Prades l’été suivant sous la direction de Pablo Casals, le 30 décembre 1952 pour le 3ème Concerto de Prokofiev avec le Philadelphia Orchestra (direction Alexander Hilsberg) et enfin les 11 et 12 avril 1953, pour le Concerto n°1 de Brahms, en lieu et place du 3ème Concerto de Prokofiev prévu initialement:

Après le concert du 1er décembre à Dallas avec le Concerto Op.15 de Brahms, le chef Walter Hendl lui a adressé une lettre dans laquelle il écrivait: « I have come to the conclusion that you are the great American pianist » (« J’en suis arrivé à la conclusion que vous êtes le grand pianiste américain »).

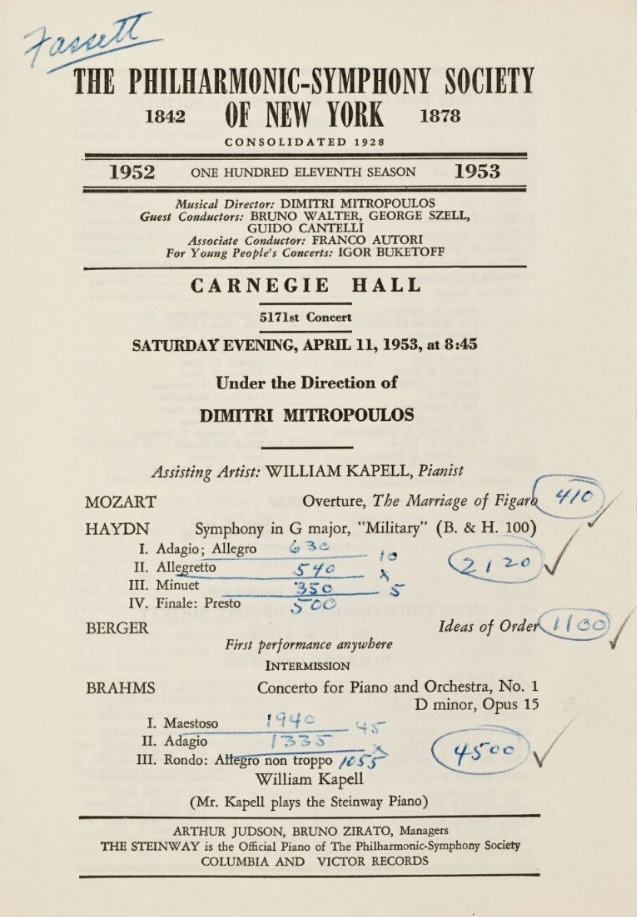

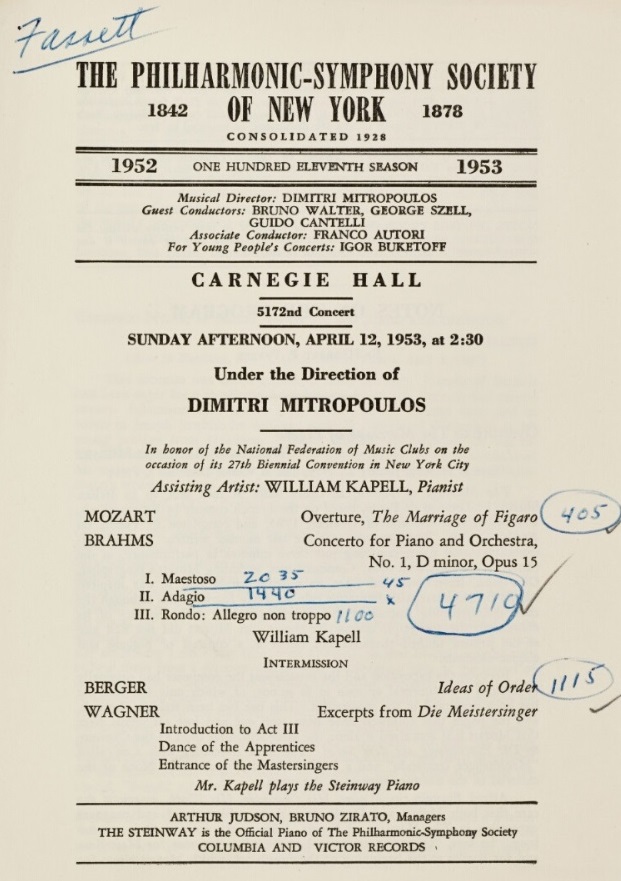

Les archives ont conservé des copies annotées des programmes des deux concerts des 11 et 12 avril 1953, et il y a de grandes différences de minutage: le 12, pour le concert radiodiffusé, les premier et deuxième mouvements durent chacun environ une minute de plus.

Nul doute que le pianiste et le chef ont modifié leur approche, probablement lors de la répétition pour le concert du dimanche, qui n’a pas le même programme que le précédent.

Bien sûr, un minutage différent n’est qu’une vague indication, mais fort heureusement, Harriett Johnson, critique du New York Post a assisté aux deux concerts et nous donne ainsi de précieux commentaires. Ainsi, lors du deuxième concert, l’interprétation était selon elle beaucoup plus détendue et de ce fait beaucoup plus éloquente. Dans ce contexte, elle pointe une tendance du pianiste à se laisser entraîner par sa propre intensité, d’où un excès de tension, une virtuosité trop marquée et une sonorité métallique. L’interprétation de l’Adagio est notée pour son intensité pénétrante, sa vitalité rayonnante et la beauté du phrasé. L’article du Musical Courier (May 1, 1953) va dans le même sens en soulignant, en ce qui concerne le premier concert, la chaleur rhapsodique de l’interprétation, mais aussi le tempo très rapide du premier mouvement, la grande virtuosité et un côté parfois plutôt percussif du jeu du pianiste.

Quoiqu’il en soit, avec ce concert radiodiffusé, nous disposons de la meilleure des deux prestations des interprètes, soliste et chef.

Musical Courier May 1, 1953 (critique du concert du 11 avril)

________________

The source that was used for the previous re-issues of this recording is truncated in the high frequencies, so that the sound is somewhat muffled which does not allow to appreciate the splendid piano sound of William Kapell (1922-1953), and also the orchestra.

The tape dubbed here is vastly superior and fully allows to hear the great performance given by Kapell for his last orchestral concert in New-York.

Fot his last complete season, Kapell performed through the United States an ambitious program of concertos, with no less than three programs in New York, namely on November 27 and 28, 1952 (with Dimitri Mitropoulos) for Mozart’s Concerto N°17 K. 453 he would later perform at the Prades Festival the following summer under the direction of Pablo Casals, on December 30, 1952 for Prokofiev’s Third Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra (conducted by Alexander Hilsberg) and to end with, on April 11 and 12, 1953 for Brahms’ First Concerto, instead of the previously scheduled Prokofiev’s Third Concerto.

After the December 1st, concert in Dallas with this Brahms Concerto, the conductor Walter Hendl sent him a letter in which he wrote « I have come to the conclusion that you are the great American pianist ».

The archives have kept annotated copies of the programs of both concerts of April 11 and 12, 1953, and there are major differences in timings: on the 12th, for the broadcast concert, each of the first and the second movements lasts about one full minute longer.

It is clear that both pianist and conductor have reconsidered their approach, probably during the rehearsal for the Sunday concert, whose program is different.

A different timing is of course merely a vague indication, but quite happily, Harriett Johnson, critic for the New York Post attended both concerts and provides us with precious comments. Indeed, at the second concert, the performance was for her much more relaxed and consequently much more eloquent. In this context, she points out the pianist’s tendency toward becoming consumed by his own intensity, the result being tension, too much emphasis on virtuosity, overplaying of the instrument and a steely tone. According to her, the performance of the Adagio was remarkable for its penetrating intensity, its glowing vitality and its beauty of phrasing. The article in the Musical Courier (May 1, 1953) goes in the same direction. It underlines, as far as the first concert is concerned, the rhapsodic warmth of the performance, but also the very fast tempo of the first movement, and the pianist’s great virtuosity and his sometimes rather percussive touch.

Be it as it may, with this broadcast concert, we have the best of the two performances, both for the soloist and the conductor.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

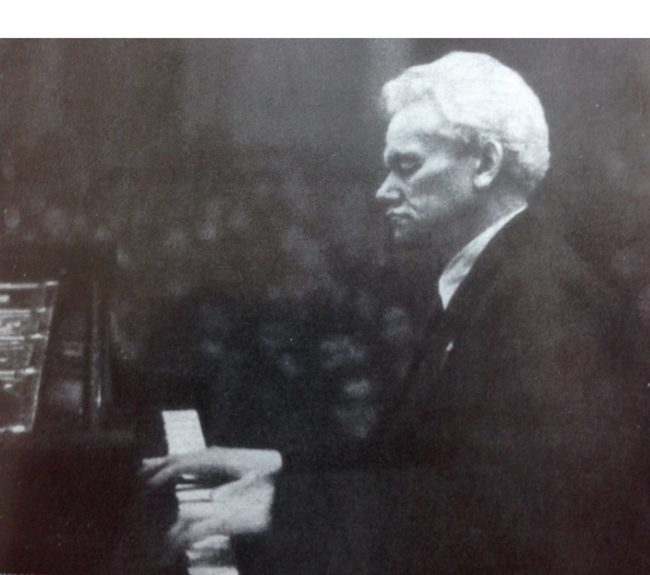

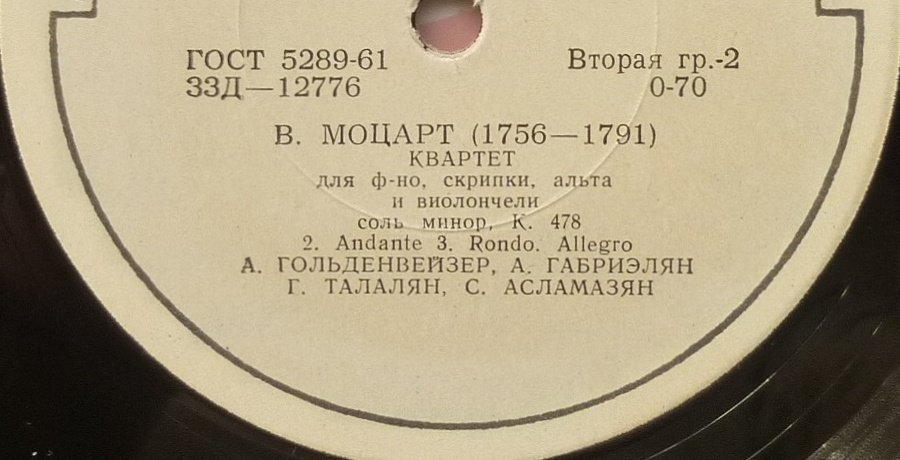

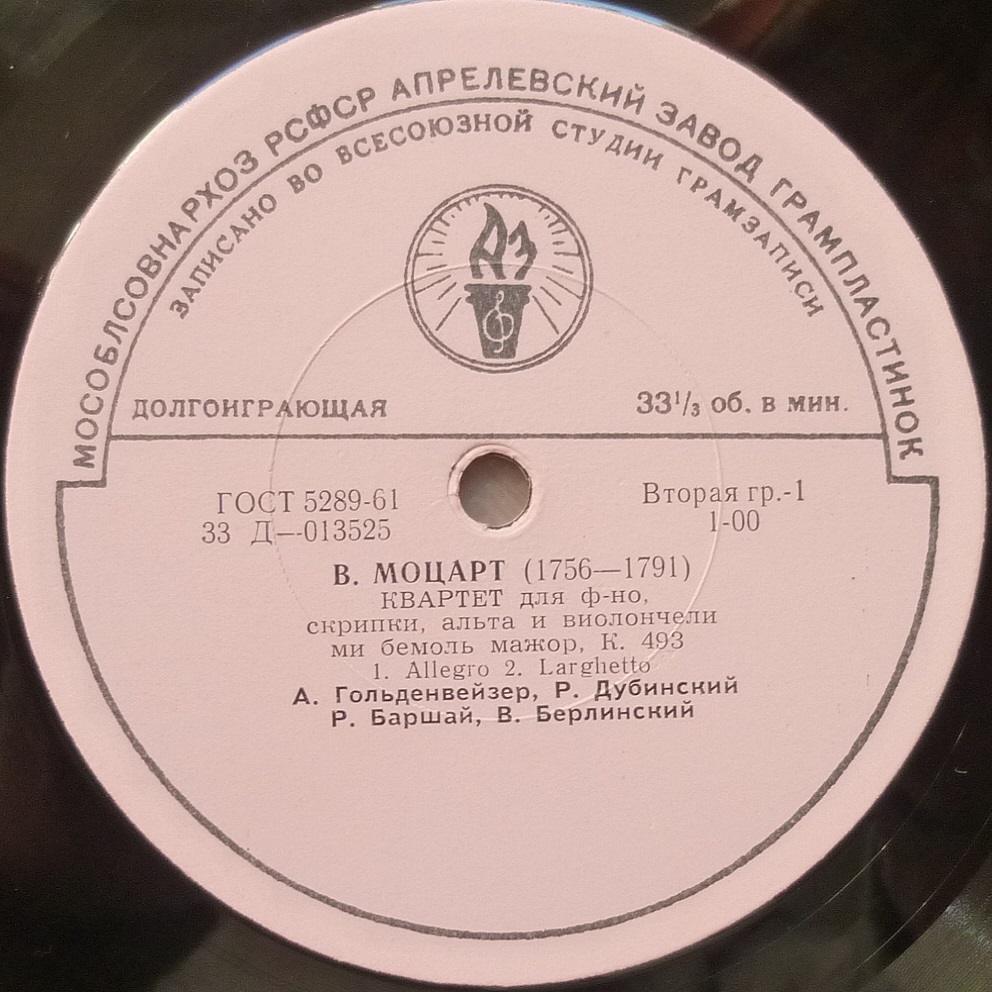

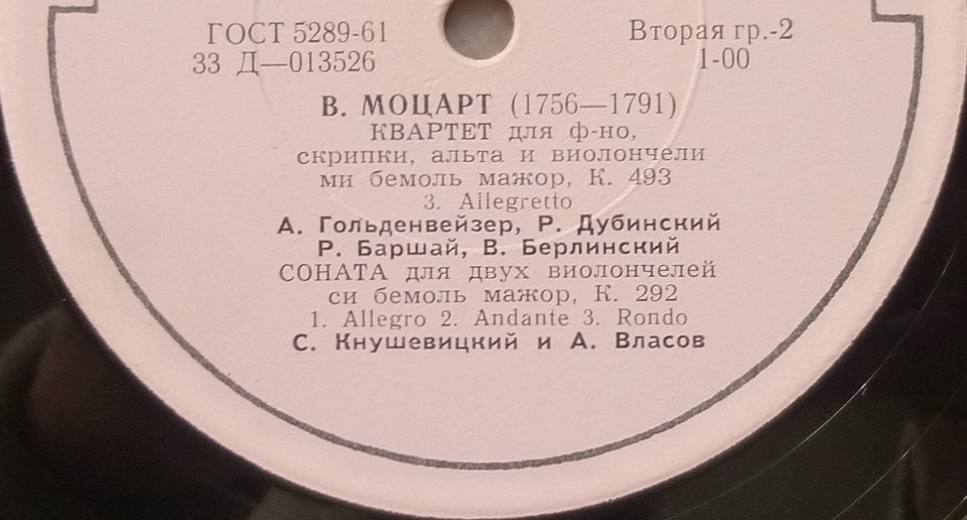

Enregistré le 20 Octobre 1950 (K.478) & le 9 Novembre 1951 (K.493)

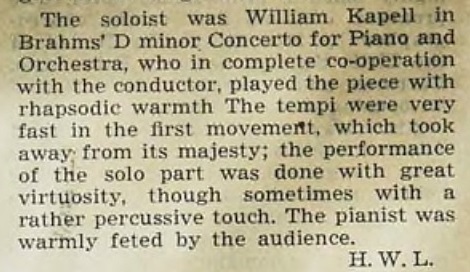

Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961), grand pianiste et grand pédagogue n’a peut-être pas de réputation particulière en ce qui concerne l’interprétation des œuvres de Mozart, mais dans ces deux Quatuors avec piano, son sens du style et de l’articulation font merveille, et sont même incroyablement modernes quand on songe qu’il est né en 1875. Pour le Quatuor n°1 K.478, il joue en collaboration avec des membres du Quatuor Komitas, et pour le Quatuor n°2 K.493 avec ceux du Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou, c’est-à-dire la dénomination initiale du Quatuor Borodine (avec Rudolf Barshaï à l’alto).

_______________

Quatuor avec piano n°1 K.478 Membres du Quatuor Komitas: Avet Gabrielyan, violon, Henrik Talalyan, alto et Sergei Aslamazyan, violoncelle

Le Quatuor Komitas a été fondé en 1924 par quatre étudiants d’origine arménienne du Conservatoire de Moscou: Avet Gabrielyan (1899-1983) et Levon Ogandjanyan, violons I et II, Mikhaïl Terian (1905-1987), alto et Sergei Aslamazyan (1897-1978), violoncelle. En 1947, Levon Ogandjanyan est remplacé par Rafael Davidyan (1923-1997) qui restera jusqu’en 1970, et Mikhaïl Terian est remplacé jusqu’en 1972 par Henrik Talalyan (1922-1972). Avet Gabrielyan restera violon I jusqu’en 1976 et Sergei Aslamazyan en tant que violoncelliste jusqu’en 1968.

Avet Gabrielyan

Henrik Talalyan

Sergei Aslamazyan

_______________

Quatuor avec piano n°2 K.493 Membres du Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou: Rostislav Dubinsky, violon, Rudolf Barshaï, alto et Valentin Berlinsky, violoncelle

Le Quatuor Philharmonique de Moscou a été fondé en 1945 par des élèves de la classe de Musique de Chambre de Mikhaïl Terian (co-fondateur du Quatuor Komitas) au Conservatoire de Moscou: Rostislav Dubinsky (1923-1997) et Vladimir Rabei, violons I et II, Yuri Nikolaïevsky (1925-2003), alto et Mstislav Rostropovitch, violoncelle pour peu de temps et vite remplacé par Valentin Berlinsky (1925-2008). Yuri Nikolaïevsky est remplacé en 1946 par Rudolf Barshaï (1924-2010). Vladimir Rabei est remplacé en 1947 par la première épouse de Rudolf Barshaï, Nina Barshaï, jusqu’à ce que Yaroslav Alexandrov (1927) lui succède en 1952. En 1953, Rudolf Barshaï quitte le Quatuor pour rejoindre le Quatuor Tchaïkovsky de Yulian Sitkovetsky (1925-1958) et est remplacé par Dmitry Shebalin. L’ensemble (Dubinsky, Alexandrov, Shebalin, Berlinsky), maintenant dénommé Quatuor Borodine, restera stable jusqu’en 1974, avec le départ de Yaroslav Alexandrov, remplacé par Andrei Abramenkov, puis en 1975, de Rostislav Dubinsky, remplacé par Mikhail Kopelman.

De gauche à droite: Rostislav Dubinsky, Valentin Berlinsky, Nina Barshaï et Rudolf Barshaï entourant Dimitri Chostakovitch

_______________

Recorded October, 20 1950 (K.478) & November, 9 1951 (K.493)

Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961), great pianist and pedagogue may not be especially famous for his performances of Mozart works, but in both of these Piano Quartets, his sense of style and of articulation are splendid, and are even incredibly modern when one thinks he was born in 1875. For Quartet n°1 K.478, he plays with Members of the Komitas Quartet, and for Quartet n°2 K.493 with those of the Moscow Philharmonic Quartet, namely the initial name of the Borodin Quartet (with Rudolf Barshaï playing the viola).

_______________

Piano Quartet n°1 K.478 with Members of the Komitas Quartet: Avet Gabrielyan, violin, Henrik Talalyan, viola and Sergei Aslamazyan, cello

The Komitas Quartet was founded in 1924 by four students of Armenian origin of the Moscow Conservatory: Avet Gabrielyan (1899-1983) and Levon Ogandjanyan, violins I and II, Mikhaïl Terian (1905-1987), viola and Sergei Aslamazyan (1897-1978), cello. In 1947, Levon Ogandjanyan is replaced by Rafael Davidyan (1923-1997) who remained until 1970, and Mikhaïl Terian is replaced until 1972 by Henrik Talalyan (1922-1972). Avet Gabrielyan remains violon I until 1976 and Sergei Aslamazyan as cellist until 1968.

_______________

Piano Quartet n°2 K.493 with Members of the Moscow Philharmonic Quartet: Rostislav Dubinsky, violin, Rudolf Barshaï, viola and Valentin Berlinsky, cello

The Moscow Philharmonic Quartet was founded in 1945 by pupils of the Mikhaïl Terian’s Chamber Music Class (Terian being one of the co-founders of the Komitas Quartet) at the Moscow Conservatory: Rostislav Dubinsky (1923-1997) and Vladimir Rabei, violins I and II, Yuri Nikolaïevsky (1925-2003), viola and Mstislav Rostropovitch, cellist for a short period and quickly replaced by Valentin Berlinsky (1925-2008). Yuri Nikolaïevsky is replaced in 1946 by Rudolf Barshaï (1924-2010). Vladimir Rabei is replaced in 1947 by Rudolf Barshaï’s first wife Nina Barshaï until Yaroslav Alexandrov (1927) comes in (1952). In 1953, Rudolf Barshaï leaves the Quartet to join the Tchaïkovsky Quartet led by Yulian Sitkovetsky (1925-1958) and is replaced by Dmitry Shebalin (1930-2013). The ensemble (Dubinsky, Alexandrov, Shebalin, Berlinsky), now named Borodin Quartet, remains the same until 1974, with the departure of Yaroslav Alexandrov, replaced by Andrei Abramenkov and in 1975, of Rostislav Dubinsky, replaced by Mikhail Kopelman.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

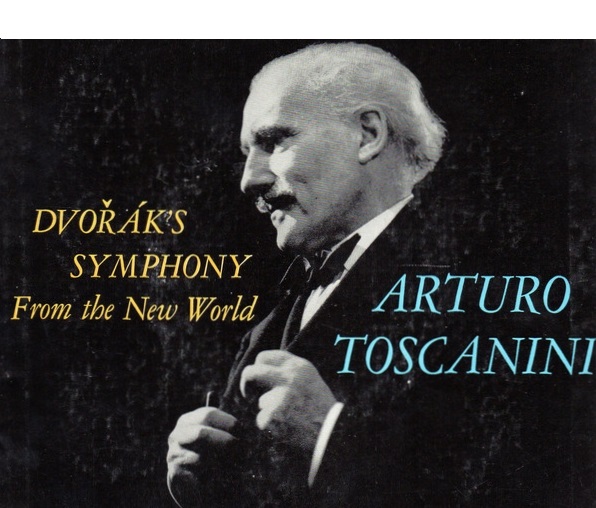

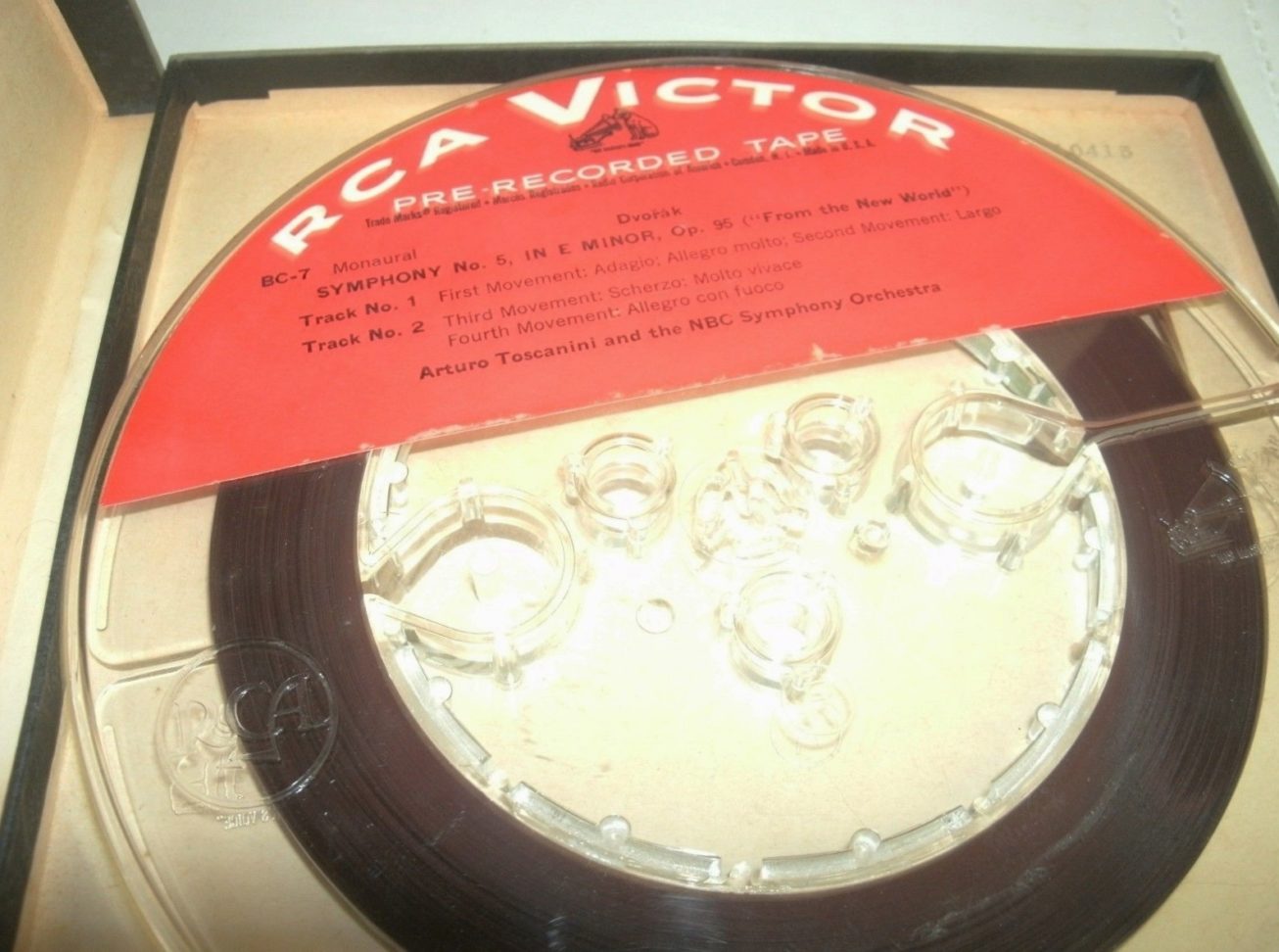

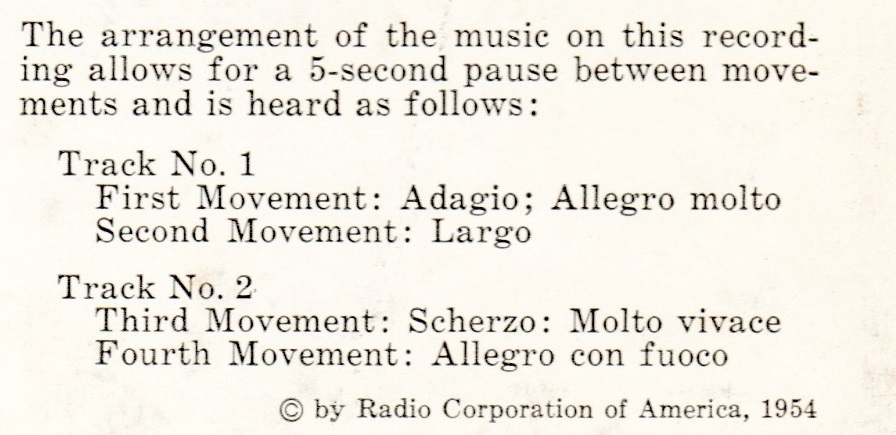

Arturo Toscanini – NBC SO

Enregistré à Carnegie Hall le 2 février 1953

Bande BC-7 (19cm/s 2 pistes) publiée en 1954

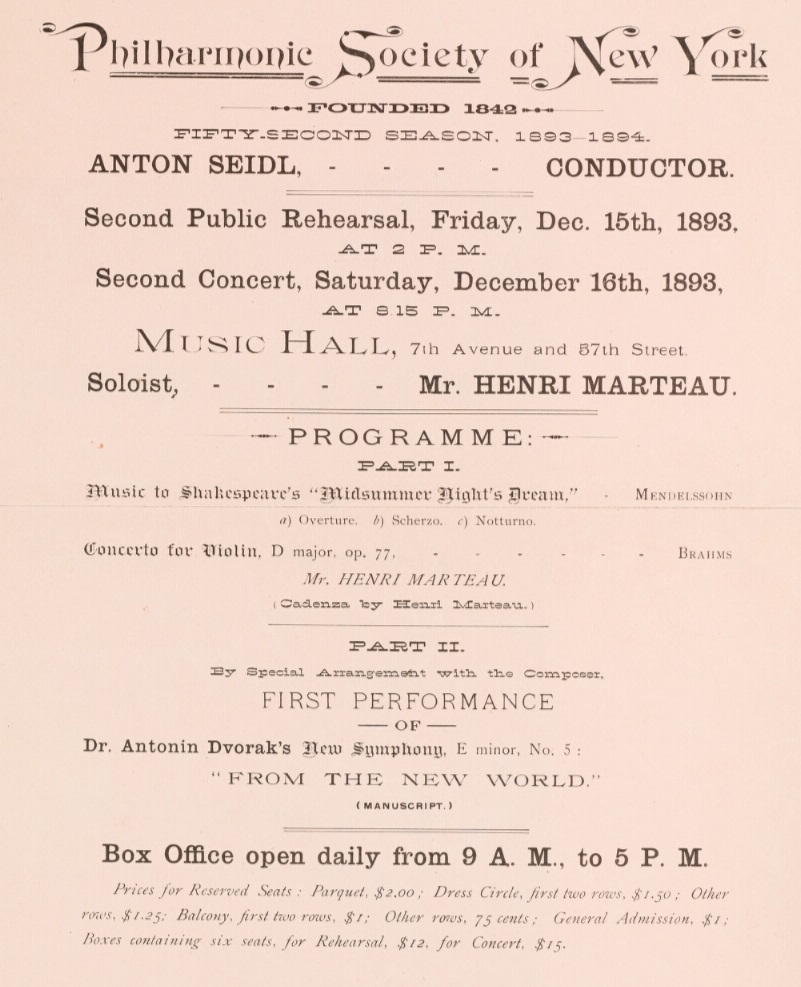

Presque 60 ans après la création de cette œuvre les 15 & 16 décembre 1893 sous la direction d’Anton Seidl (1850-1898) dans cette même salle alors dénommée « Music Hall 7th Avenue and 57th Street » avant de devenir le célèbre « Carnegie Hall », Toscanini, qui a dirigé l’oeuvre dès 1898, nous en laisse un témoignage qui reste un fleuron de ses dernières saisons à la tête du NBC Symphony Orchestra.

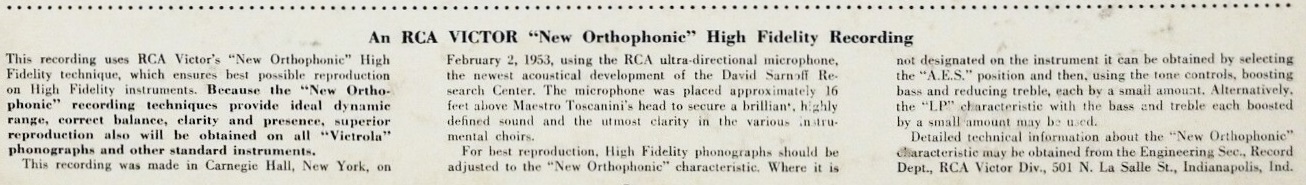

A partir de 1952, RCA a modifié sa technique d’enregistrement, du moins en ce qui concerne Toscanini. La captation a été réalisée avec un seul microphone positionné environ 5 mètres au dessus du chef, la même technique que celle déployée à l’époque par d’autres firmes telles que Mercury ou Westminster. Il en résulte une perspective sonore et une dynamique naturelles que l’on n’avait pas l’habitude d’entendre dans ses disques et qui sont magnifiées par l’édition sur bande (19 cm/s, 2 pistes), laquelle surclasse les publications en microsillon et en CD, en restituant des subtilités de phrasé et de rythme que l’on pensait n’exister que dans l’enregistrement du concert du 31 janvier précédant cet enregistrement.

Extrait du texte de présentation du 33t. LM-1778

Nearly 60 years after the work was premiered on December 15 & 16 1893 under the direction of Anton Seidl (1850-1898) in the same Hall then called « Music Hall 7th Avenue and 57th Street » before it came universally known as the « Carnegie Hall », Toscanini, who performed the work as early as 1898, gives us a testimony which remains one of the main highlights of his last seasons with the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

As of 1952, RCA changed its recording technique, at least as far as Toscanini was concerned. This recording was made with a single microphone placed approximately 16 feet above the conductor’s head, namely the same technique as implemented then by companies like Mercury or Westminster. This accounts for a natural sound perspective and natural dynamics seldom heard before in his recordings and that are enhanced by the tape issue (7.5 ips; 2 tracks), which outdoes the LPs and CDs, unveiling subtilities of phrasing and of rhythm that were believed to exist only in the recording of the concert given shortly before on January 31.

___________________

___________________

___________________

___________________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.