Catégorie : Non classé

Symphonie n°2 D.125: 13-17 mars 1959

Prod: Erik Smith Eng: James Brown

(Bande 19cm/s 4 pistes London LCL 80038)

Symphonie n°3 D.200: 22-25 février 1965

Prod: Ray Minshull Eng: Gordon Parry

(Bande 19cm/s 4 pistes London LCL 80180)

Wien Sofiensaal

________

Karl Münchinger (1915-1990) a enregistré six symphonies de Schubert avec les Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO). Son style de direction et son expérience des orchestres de chambre conviennent tout particulièrement à ce répertoire pour lequel cet orchestre est évidemment idéal.

Karl Münchinger (1915-1990) recorded six Schubert Symphonies with the Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO). His conducting style as well as his practice of chamber orchestras are especially suitable for these works, and this orchestra is of course ideal.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

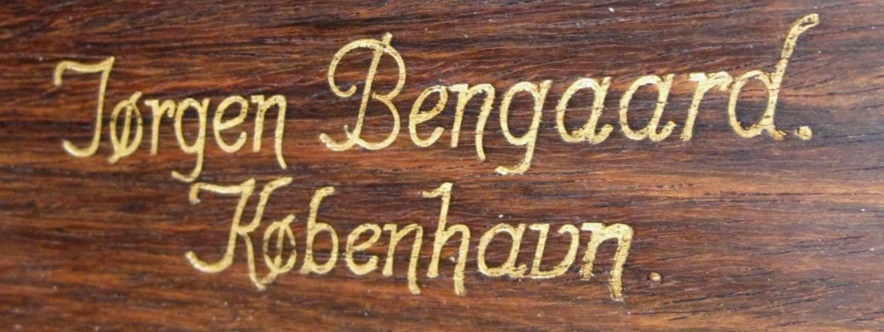

Huguette Dreyfus clavecin Jørgen Bengaard

Enregistré à Copenhague en 1965 Prise de son: Peter Willemoës

Microsillon Valois 77002

Les Toccatas pour clavecin de Bach sont bien moins souvent enregistrées que ses autres œuvres dédiées à cet instrument. Pourtant, elles représentent une étape importante de l’évolution du compositeur. Comme l’écrivait Harry Halbreich: « C’est au clavecin que la Toccata de type buxtehudien allait fêter son apothéose inattendue sous l’impulsion du génie d’un Bach de vingt-cinq ou trente ans en pleine révolution artistique. Les sept Toccatas BWV 910 à 916 représentent l’ensemble le plus important d’œuvres de jeunesse de Bach pour clavecin et le témoignage le plus frappant de sa phase de révolutionnaire romantique soulevé par le Sturm und Drang« .

Buxtehude a eu une influence déterminante sur le jeune Bach, et elle date de bien avant son voyage en 1705 à Lübeck, car on sait qu’à l’âge de treize ans, alors qu’il résidait chez son frère aîné Johann Christoph à Ohrdruf, il avait copié de sa main la grande Fantaisie-Choral « Nun freut euch lieben Christen g’mein (BuxWV210).

Huguette Dreyfus (1928-2016) possédait un clavecin français Blanchet datant du XVIIIème siècle, mais comme elle ne voulait pas le faire voyager, elle s’est décidée à faire ses enregistrements pour le label Valois sur un clavecin du facteur danois Jørgen Bengaard qui était la propriété de l’organiste Jørgen Ernst Hansen. Ce n’est que plus tard, au tournant des années 70, après sa rencontre avec Claude Mercier-Ythier, qu’elle pourra utiliser son précieux clavecin Henri Hemsch de 1754 sur lequel elle fera désormais ses enregistrements.

Au fond, sa démarche était similaire à celle de son contemporain Gustav Leonhardt qui, à la même époque, plutôt que d’enregistrer sur un clavecin historique, a fait également appel à un artisan peu connu, Martin Skowroneck, à ceci près que son instrument, inspiré d’un clavecin Dulcken (Antwerpen 1745), était de sonorité sensiblement plus proche des instruments historiques que celui de Bengaard. L’instrument touché par H. Dreyfus n’en présentait pas moins une densité de son et une variété de couleurs appropriée au style très libre de ces Toccatas.

Les œuvres sont présentées dans l’ordre chronologique. Les Toccatas en ré mineur BWV 913 et mi mineur BWV 914 datant probablement de 1707-1708, alors que les deux autres, en fa dièze mineur BWV 910 et en ut mineur BWV 911, également composées à Weimar sont un peu plus tardives, au plus tard de 1713.

_______________

Dreyfus – J-S Bach – Toccatas for harpsichord BWV 913, 914, 910 & 911

Huguette Dreyfus harpsichord (Jørgen Bengaard)

Recorded in Copenhagen 1965 (Ing. Peter Willemoës)

Valois LP 77002

Bach’s Toccatas for harpsichord are much less recorded than his other works for this instrument. Howevern they represent an important step in the composer’s evolution. As Harry Halbreich wrote : « With the harpsichord, the Buxtehude type Toccata met an unexpected apotheosis under the impulse of the genius of a twenty-five or thirty- years old Bach in a full artistic revolution. The seven Toccatas BWV 910 to 916 are the most important group of harpsichord works from Bach’s youth and the most striking testimony of his period as a romantic revolutionary roused by Sturm und Drang« .

Buxtehude had a major influence on the young Bach , and this dates back to much earlier than his 1705 travel to Lübeck. Indeed, it has been discovered that at the age of thirteen, when he was living in Ohrdruf with his elder brother Johann Christoph, he made a hand copy of the great organ Choral Fantasy « Nun freut euch lieben Christen g’mein (BuxWV210).

Huguette Dreyfus (1928-2016) owned a French Blanchet XVIIIth century harpsichord, but since she did not want to travel with it, she decided to make recordings for the Valois label on a harpsichord by Danish builder Jørgen Bengaard owned by organist Jørgen Ernst Hansen. Only later, around 1970, after she met Claude Mercier-Ythier, was she allowed to use his rare Henri Hemsch 1754 harpsichord on which she then made her recordings.

In fact, her approach was akin to Gustav Leonhardt’s who during same period, rather than recording on an historical harpsichord, also had resort to an almost unknown independent builder, Martin Skowroneck. But his instrument, inspired by a Dulcken harpsichord (Antwerpen 1745), sounded somewhat closer to the historical instruments than Bengaard’s. Nevertheless, the instrument played by H. Dreyfus had a density of tone and a variety of coulours well adapted to the very free style of these Toccatas.

The works are presented in chronological order. The Toccatas in D minor BWV 913 and E minor BWV 914 were probably composed in 1707-1708, whereas the other two, in F sharp minor BWV 910 and C minor BWV 911, also composed in Weimar came a little later, in 1713 at the latest.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

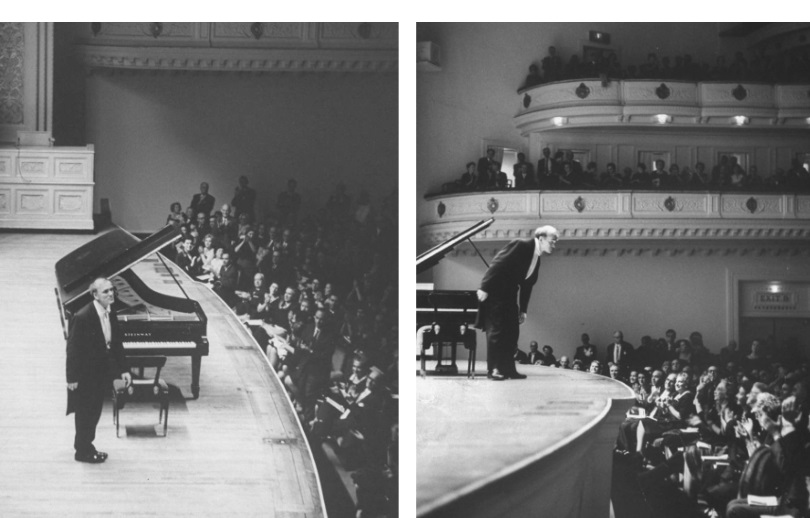

Sviatoslav Richter Carnegie Hall 18 mai 1965

Disque 33 tours Melodiya M10- 47287 paru en 1986

L’enregistrement de la Sonate de Liszt provenant du concert du 18 mai 19651 à Carnegie Hall était de loin celui que Richter préférait, au point d’en promouvoir lui-même la publication.

On trouve ainsi dans ses Carnets (in « Richter Écrits, Conversations » Ed Van De Velde/Actes Sud 1998):

8 janvier 1981: Lorsque j’ai joué la Sonate de Liszt au Carnegie Hall, notre imprésario américain Sol Hurok n’avait invité aucun critique musical de la presse new-yorkaise, et ce concert effectivement très réussi est passé totalement inaperçu. Irina Volkonska, la fille de Rachmaninov, m’avait fait la joie de venir, de dire des choses très flatteuses à mon endroit, et de fustiger le célèbre critique new-yorkais Harold Schonberg qui s’était montré extrêmement hostile à mon égard.

16 janvier 1981 (Studio Melodiya – Écoute d’enregistrements): Cet enregistrement contient pas mal de défauts techniques, ce qui ne me dérange en rien, et il me semble exceptionnellement réussi…. La Sonate est quasiment dépourvue de scories du début à la fin, et elle a un élan et un climat qui en font une évidente réussite. Que faut-il de plus?

Malgré son insistance à obtenir la parution de ce disque, il faudra cinq ans pour qu’il soit enfin mis à la disposition du public.

18 août 1986: Ce disque si attendu est enfin paru, et toute notre compagnie s’est rassemblée dans ma chambre pour l’écouter. Succès garanti. Sur la table, il y a les restes du dîner, des bouteilles de kéfir, des miettes de pain noir, et tout à l’avenant. Voyage au pays des Soviets…

![]()

En 1990, Philips a publié un CD 422137-2 qui était un repiquage du microsillon Melodiya M10-472872, avec pour la Sonate une date d’enregistrement erronée « Budapest 1960 ».

Dans le coffret Philips 442-464-2 (21 CD), il y a un enregistrement, musicalement très inférieur, de cette Sonate qui provient d’un concert à Livorno, le 21 novembre 1966, qui ne semblait pas avoir reçu l’accord du pianiste puisque dans ses notes du 25 novembre 1994, il indiquait que le coffret en question contiendrait des enregistrement qu’il n’avait jamais écouté.

En tous cas, l’enregistrement de la Sonate de Liszt lors du concert du 18 mai 1965, qui était un de ceux auquel il tenait le plus parmi son énorme discographie, mériterait évidemment une publication officielle à partir de la bande originale.

1 Le programme de ce concert était le suivant: Liszt Sonate S178; Chopin Scherzo n°1 Op.20; Ravel Pavane pour une Infante Défunte – Gaspard de la Nuit (Gibet) – Jeux d’Eau – Scriabine Sonate n°7 Op.64 « Messe Blanche ».

2 La source utilisée pour graver le disque Melodiya restitue l’ampleur du son du piano de Richter avec une dynamique élevée. Toutefois, la gravure, peu soignée, présente pas mal de problèmes, notamment un bruit rythmique dans le grave. Pour son CD, Philips a eu recours à un logiciel de réduction de bruits pour atténuer certains de ces défauts qui restent nettement perceptibles. Le piano sonne un peu étouffé en comparaison avec le microsillon, et on perd en détails, mais le résultat reste très correct.

3 Dans sa note du 10 janvier 1990, Richter se prononce au sujet de l’enregistrement de la Sonate de Liszt lors d’un Concert à Aldeburgh (21 juin 1966): « Forte et convaincante expression (les quelques fausses notes ne me dérangent guère). Je ne sais pas, sans doute bon. Oleg Kagan dit que si cela n’était pas banal, il se serait mis à genoux« . Cet enregistrement, le seul avec celui de Carnegie Hall à avoir été commenté favorablement par Richter, a été publié par BBC Legends (BBCL 4146-2 ou coffret 4 CD BBC 5004-2).

____________________

Richter – Liszt Sonata in B minor S178

Sviatoslav Richter Carnegie Hall May 18, 1965

Melodiya LP M10- 47287 published in 1986

The recording of the Liszt Sonata from this 1965 Carnegie Hall Concert1 was by far Richter’s favorite, to such a point that he himself promoted its publication.

We thus find in his Notebook (in « Richter Écrits, Conversations » Ed Van De Velde/Actes Sud 1998):

January 8, 1981: When I performed Liszt’s Sonata at Carnegie Hall, our US impresario Sol Hurok invited no music critic from the New-York press, and this effectively very successful concert was unnoticed. It was for me a joy that Irina Volkonska, Rachmaninov’s daughter, came to the concert, said very flattering things about me, and shunned the famous New-York critic Harold Schonberg who was very hostile against me.

January 16, 1981 ( Melodiya Studio – Listening to recordings): This recording has many technical flaws, which doesn’t bother me at all, and seems to me exceptionnally successful…. The Sonata is almost without mishaps from beginning to end, and it has a sweep and a ambiance that make of it an obvious success. What else is needed?

In spite of his insistence on obtaining the publication of this record, he had to wait five years before it was made available to the public.

August 18, 1986: This eagerly awaited record is available at last, and our whole group assembled in my room to listen to it. Guaranteed success. On the table, there are the remains of the supper, bottles of kefir, crumbs of black bread, and everything in keeping. Travel in the country of Soviets…

In 1990, Philips published a CD 422137-2 that was a dub of the Melodiya LP M10-472872, with an erroneous recording date for the Sonata « Budapest 1960 ».

In the Philips Box Set 442-464-2 (21 CDs), there is a musically much inferior recording of this Sonata coming from a concert in Livorno, on November, 21 1966, which seems not to have received an agreement from the pianist, since in his note dated November, 25 1994, he mentioned that he had not even been granted the possibility of listening to some of the recordings published therein.

Be it as it may, the recording of the Liszt Sonata from the May 18, 1965 concert, which was one of those he treasured most in his enormous discography, would obviously deserve to be officially published from the original master tape.

1 The program of the concert was as follows: Liszt Sonata S178; Chopin Scherzo n°1 Op.20; Ravel Pavane pour une Infante Défunte – Gaspard de la Nuit (Gibet) – Jeux d’Eau – Scriabine Sonata n°7 Op.64 « Messe Blanche ».

2 The source used to cut the Melodiya LP reproduces Richter‘s large piano sound with high dynamics. However, the LP, not produced with due care, has many problems, especially a rhythmic noise in the lower register. For its CD, Philips had resort to a noise reduction software to cope with some of these defects which however remain easily noticeable.. The piano sounds somewhat muffled in comparaison with the LP, and details are lost, but the result is still very honest.

3 In his note dated January, 10 1990, Richter discusses the recording of the Liszt Sonata from the Aldeburgh Concert of June, 21 1966: « Strong and convincing expression (the few wrong notes hardly bother me). I don’t know. It’s good, no doubt. Oleg Kagan says that were it not commonplace, he would have kneeled down ». This recording, the only one with the one from Carnegie Hall to have been commented favourably by Richter, has been published by BBC Legends (BBCL 4146-2 or 4CD set BBC 5004-2).

______________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

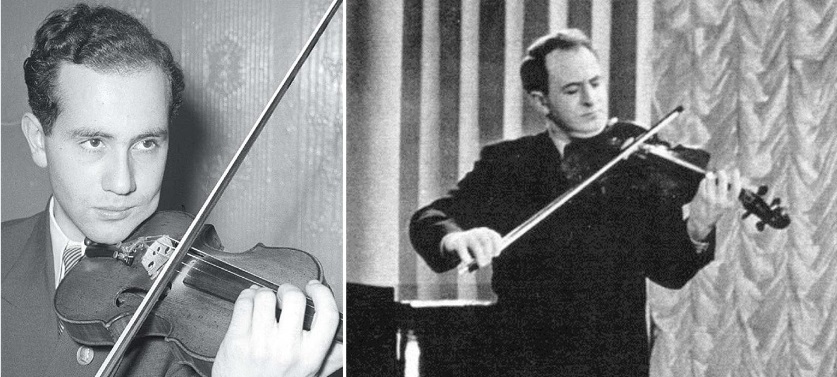

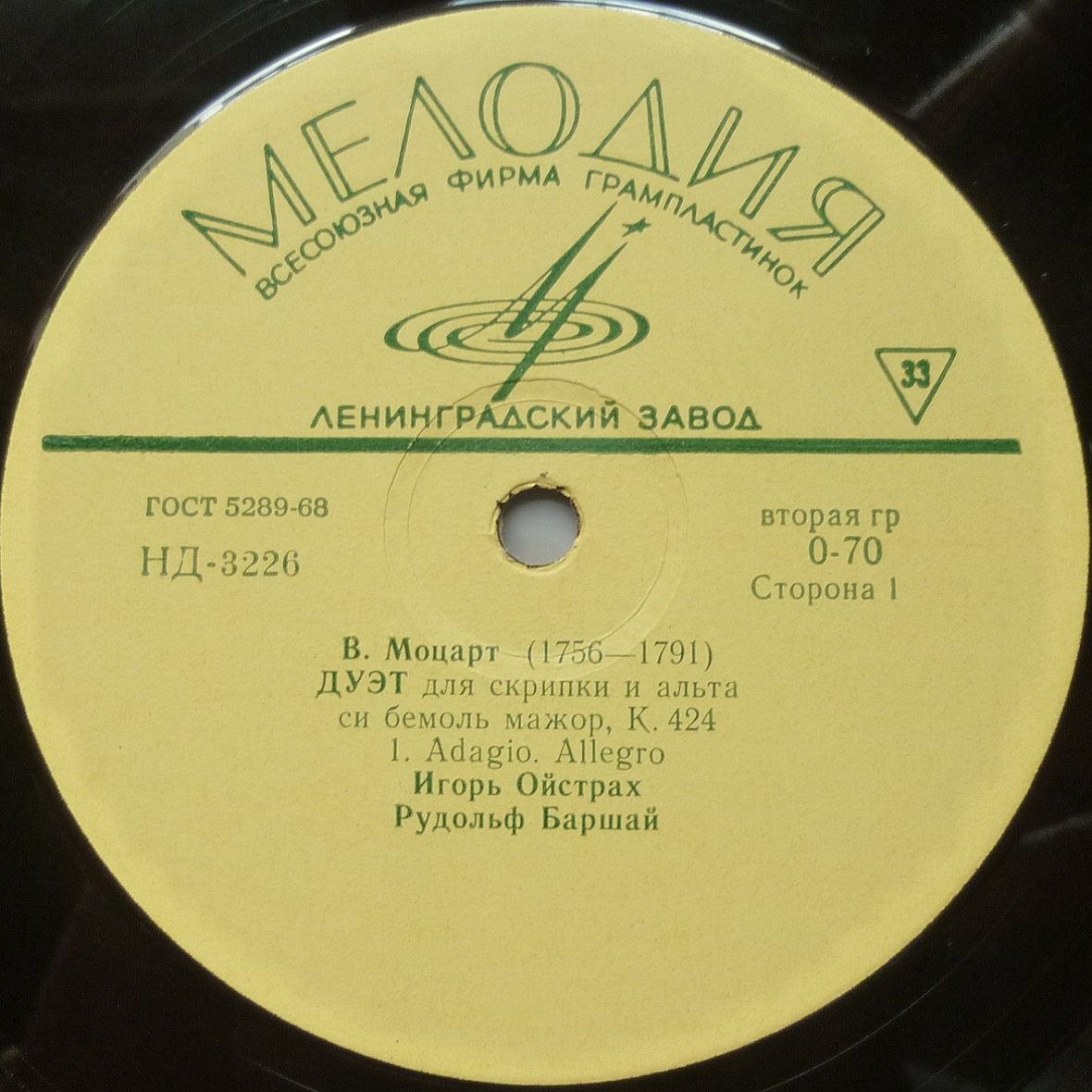

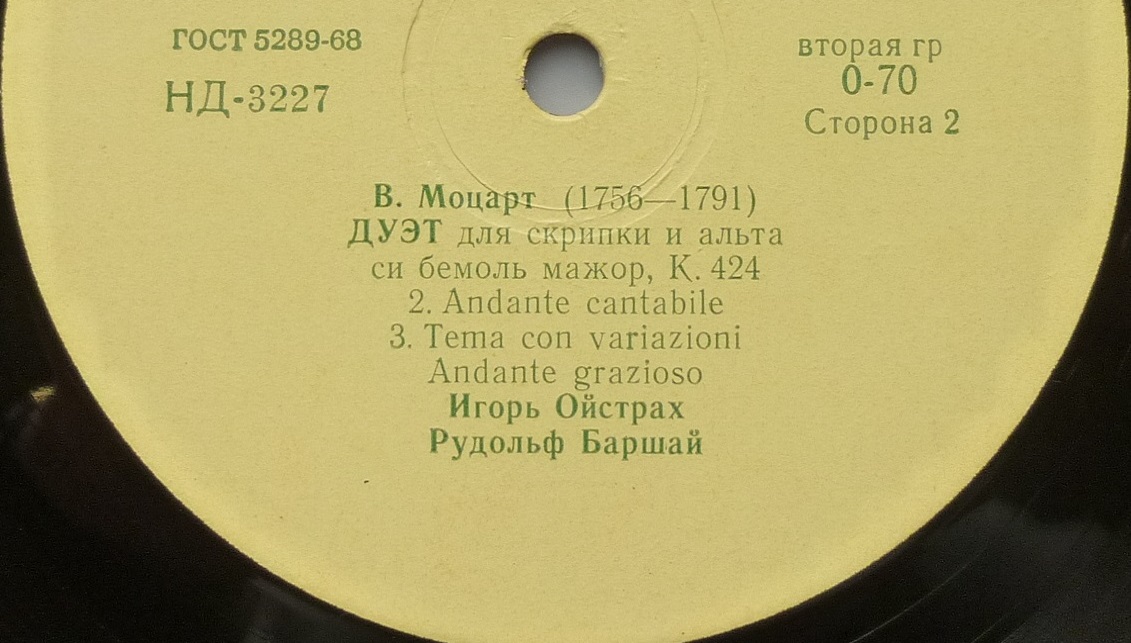

Igor Oïstrakh & Rudolf Barshaï Duos K423 & 424

David Oïstrakh & Rudolf Barshaï Orchestre de Chambre de Moscou Sinfonia Concertante K364

L’enregistrement des deux duos violon-alto K423 & 424 de Mozart a été réalisé en 1955/1956 par Igor Oïstrakh, violon et Rudolf Barshaï, alto et publié en 1956 à l’occasion du bi-centenaire de la naissance de Mozart.

Depuis, il n’a pas été réédité et a même été oublié au point que des discographies de David Oïstrakh mentionnent de manière erronée celui-ci comme étant le violoniste du duo K424 sur le disque Melodiya D3226.

C’est fort dommage, car la rigueur du style et la conduite du discours musical sont en parfaite équation avec ces œuvres classiques, alors que certains autres interprètes tombent dans l’écueil d’un phrasé romantique qui rompt la continuité du flux musical polyphonique.

En Hommage à Igor Oïstrakh pour ses 90 ans.

L’enregistrement en studio de la Sinfonia Concertante K364 par David Oïstrakh et Rudolf Barshaï avec l’Orchestre de Chambre de Moscou dirigé par R. Barshaï date de 1959/1960 est bien sûr beaucoup plus connu, même si sa disponibilité reste aléatoire. La source est ici un microsillon Musidisc 30 RC 859. Il existe par ces mêmes interprètes une version en public du 11 septembre 1963 publiée sous le label « Moscow Conservatory Records » (SMC CD 0021).

The recording of the two violin-viola duets K423 & 424 by Mozart has been made in 1955/1956 by Igor Oïstrakh, violin and Rudolf Barshaï, viola and published in 1956 for the Bicentenary of Mozart’s birth.

Since then, it hasn’t been reissued, and even forgotten to the extend that some David Oïstrakh discographies erroneously mention him as being the violonist for Duet K424 on the Melodiya LP D3226.

Just too bad, since the purity of style and the musical discourse perfectly match these classical works, whereas some other interprets would indulge in romantic phrasings thus breaking the continuity of the polyphonic musical flow.

As a Tribute to Igor Oïstrakh, born 1931.

_____________

The studio recording of the Sinfonia Concertante K364 by David Oïstrakh and Rudolf Barshaï with the « Moscow Chamber Orchestra » led by R. Barshaï was made in 1959/1960 and is of course much better known, although its availability is somewhat random. Here, the source is a Musidisc LP (30 RC 859). A live recording by the same performers on September, 11 1963 has been published by « Moscow Conservatory Records » (SMC CD 0021).

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

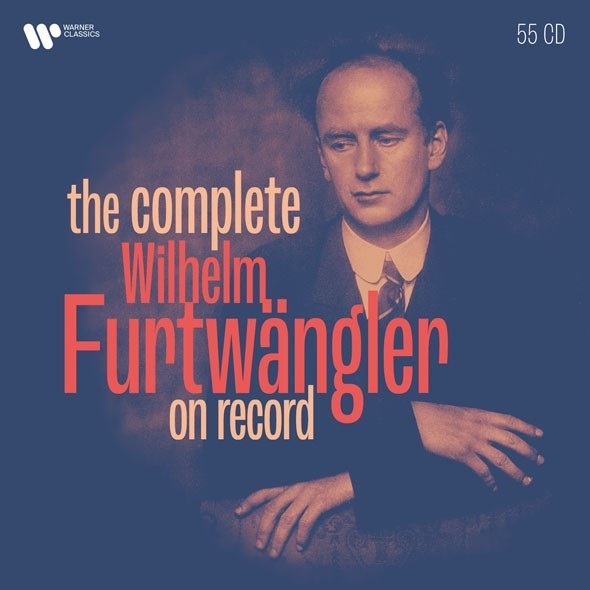

Warner vient d’annoncer la publication le 24 septembre prochain d’un coffret de 55 CD consacré à la totalité des enregistrements réalisés par Wilhelm Furtwängler, non seulement pour le groupe EMI, mais également sous les labels Polydor, Telefunken, Decca et DGG.

La composition des 55 disques de cette compilation est donnée ici:

https://hdarchivesconcerts.fr/coffret-warner-55-cd-the-complete-wilhelm-furtwangler-on-record/

Une première analyse sur la base des renseignements publiés par Warner est publiée ici:

Au sujet du Coffret « The Complete Wilhelm Furtwängler on Record »

Warner has just announced the publication on September 24 of a 55 CD Album dedicated to all the recordings made by Wilhelm Furtwängler not only for the EMI group, but also for the other labels Polydor, Telefunken, Decca and DGG.

The track listing of the 55 CDs is presented here:

https://hdarchivesconcerts.fr/coffret-warner-55-cd-the-complete-wilhelm-furtwangler-on-record/

A primary analysis based on the documentation published by Warner is here:

Comments on « The Complete Wilhelm Furtwängler on Record »