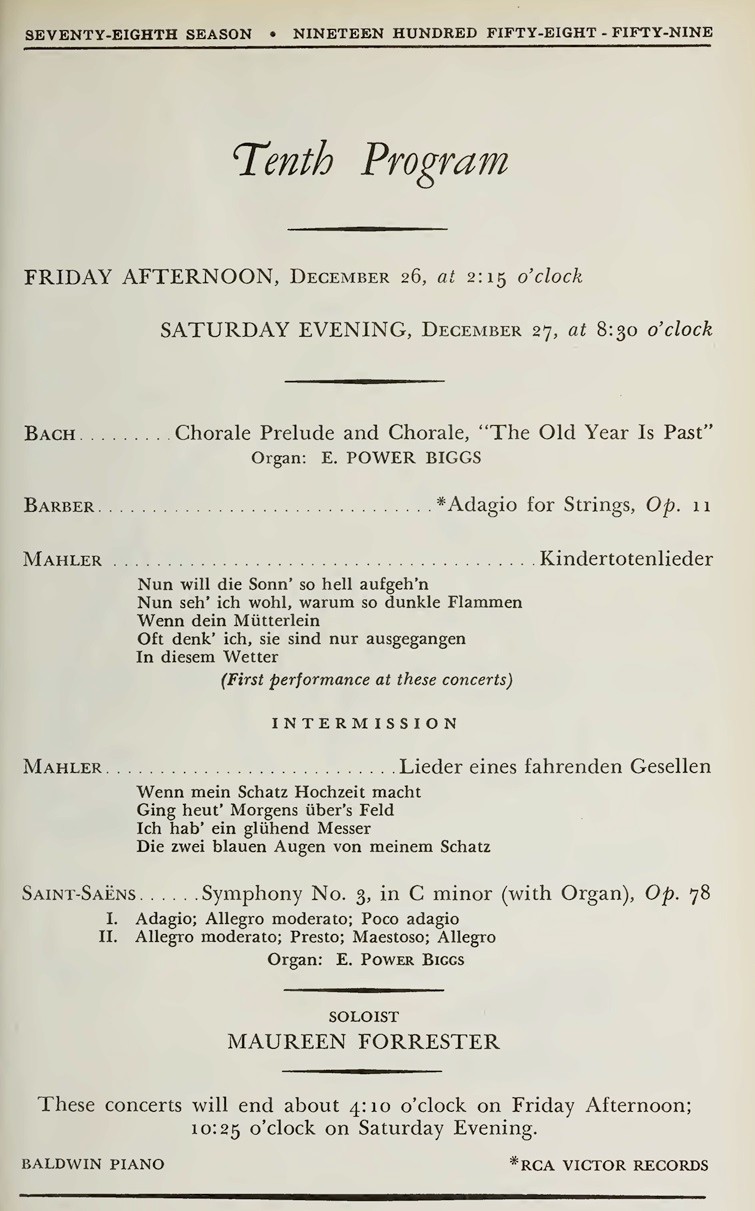

Forrester – III – Mahler: Kindertotenlieder – Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen – Munch BSO

Maureen Forrester, contralto

Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch

Boston Symphony Hall – December 27 1958

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Les enregistrements de Maureen Forrester sont des joyaux de la discographie mahlérienne. On ne ne connait pas la raison du choix de Charles Munch pour diriger ces œuvres, car c’est quasiment la seule fois où, avec le BSO, il a abordé ce compositeur. Le fait est que le disque commercial qui en est résulté est réussi, tant du point de vue du chant que de la direction.

C’est la première fois que les Kindertotenlieder sont donnés par le BSO dans le cadre des concerts d’abonnements à Boston. Auparavant, Marcia Davenport les avait chantés en 1944 avec des membres du BSO sous la direction de Bernard Zighera, et en 1949 le Festival de Tanglewood les avait programmés avec Helen Spaet sous la direction d’Howard Shanet.

Mahler avait été précédemment beaucoup plus joué à Boston qu’on ne le pense:

Symphonie n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphonie n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphonie n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphonie n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphonie n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphonie n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky n’était pas du tout répertorié comme chef mahlérien, et après lui, la direction des œuvres de Mahler a été, au cours des années cinquante, surtout confiée à Richard Burgin, le « concert-master » de l’orchestre (notamment les Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen en 1952), plutôt qu’à des chefs invités.

Le concert du 27 décembre 1958 est la plus ancienne archive conservée en stéréo du BSO en public. L’interprétation en concert se caractérise par une très grande écoute réciproque entre la soliste et les membres de l’orchestre que le chef laisse heureusement se développer. Rappelons que Munch a été pendant plusieurs années un des violons solo du Gewandhausorchester de Leipzig, qui était surtout l’orchestre de l’Opéra, et qu’en cette qualité, il avait acquis une grande expérience de l’accompagnement des solistes.

Le choix du reste du programme n’était pas particulièrement heureux. Pour terminer, Munch s’était en effet livré dans la Symphonie n°3 de Saint-Saëns à une des prestations spectaculaires qu’il affectionnait, ici relativement bien mise en place, et qui lui ont valu à la fois beaucoup de succès et beaucoup de critiques.

Maureen Forrester’s recordings are jewels of the Mahler discography. It is not known why Charles Munch was chosen to conduct these works, since it is the only time he conducted them, and almost the only time he conducted this composer with the BSO. Anyway, the commercial recording that came out of it was successful, for the singing as well as the conducting.

It was the first time that the Kindertotenlieder were performed at the BSO abonnement concerts. Earlier, Marcia Davenport sang them in 1944 with members of the BSO conducted by Bernard Zighera, and in 1949 they were performed at the Tanglewood Festival by Helen Spaet and conducted by Howard Shanet.

In Boston, Mahler was previously performed more than one thinks:

Symphony n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphony n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphony n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphony n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphony n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphony n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky did not have a reputation as a Mahler conductor, and after him, during the 50’s his works were mostly conducted by Richard Burgin, the orchestra « concert-master » (a.o. the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen in 1952), rather than by invited conductors.

The December 27, 1958 concert is the oldest stereo archive from the BSO live. The public performance shows a quite great mutual hearing between the soloist and the orchestra members which the conductor lets develop freely. For several years, Munch was one of the « Konzertmeister » of the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, mainly performing at the Opera, and he then acquired a great experience with the accompaniment of singers.

The remainder of the program was not particularly well chosen. To end the concert, Munch delivered in Saint-Saëns’ Symphony n°3 one of the spectacular performances he was fond of, rather well in place, of a type that owned him plenty of successes as well as criticisms.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

7 réponses sur « Forrester – III – Mahler: Kindertotenlieder – Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen – Munch BSO »

HD/Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.com/publink/show?code=kZVlO5ZRRyUkQxhcf8Ltb1sziNCRktg2LdX

Format CD (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.com/publink/show?code=kZRBG5Z6G7FiuU77R4R48JYM51psJ6rpFhV

Thank You. What a radiostation the program was broadcasted?

WGBH FM took over in 1951 the broadcast of the BSO concerts from NBC, and as can be seen was much ahead of time as to stereo FM.

Thanks so much once again for sharing these treasures with us in excellent sound!

The broadcast was recorded by Jordan Whitelaw and his team in the glorious acoustics of Symphony Hall, and in the booth was the ‘voice’ of WGBH Radio, William (Bill) Pierce.

Fantastic post !

I think it is a better performance than the RCA recording made immediately afterwards in the same venue. The microphone placement, less close, is also more appropriate to the chamber orchestra aspect of some of the performance. With the public, the acoustics of the Boston Symphony Hall is parfectly balanced whereas the empty hall has a slight resonance in the lower frequencies.