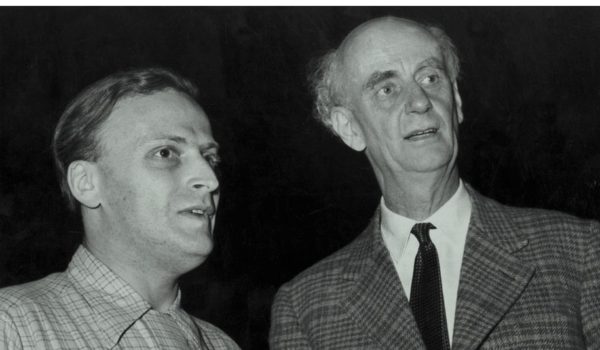

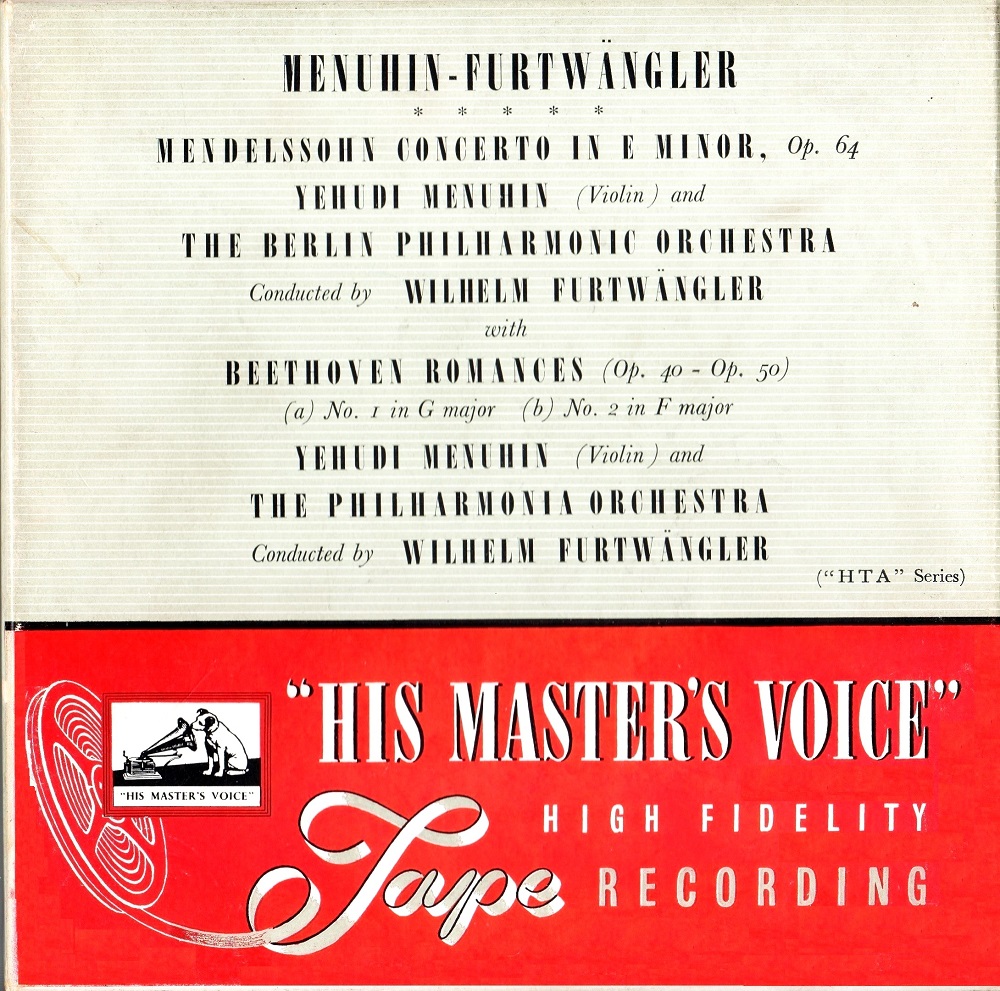

Yehudi Menuhin & Wilhelm Furtwängler

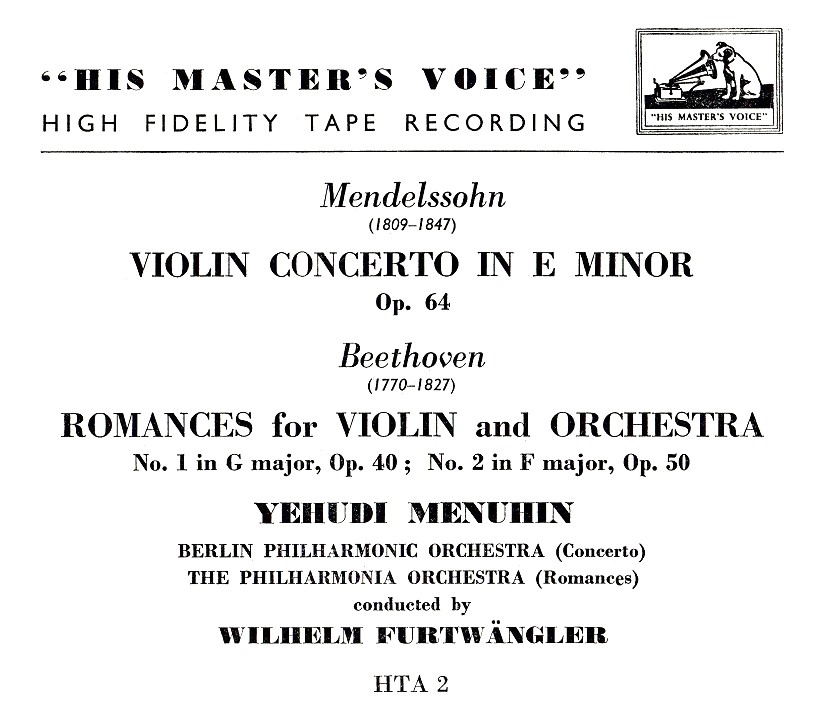

Mendelssohn: Concerto Op.64 Berliner Philharmoniker (BPO)

Berlin Jesus-Christus Kirche – 25 & 26 Mai 1952

Eng: Robert Beckett

______

Beethoven: Romances Op.40 & 50 Philharmonia Orchestra

London Kingsway Hall – 9 April 1953

Prod: Lawrence Collingwood & David Bicknell – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTA 2

Menuhin et Furtwängler ont joué pour la première fois ensemble le Concerto Op.64 de Mendelssohn le 29 septembre 1949 au Royal Albert Hall de Londres avec les Wiener Philharmoniker.

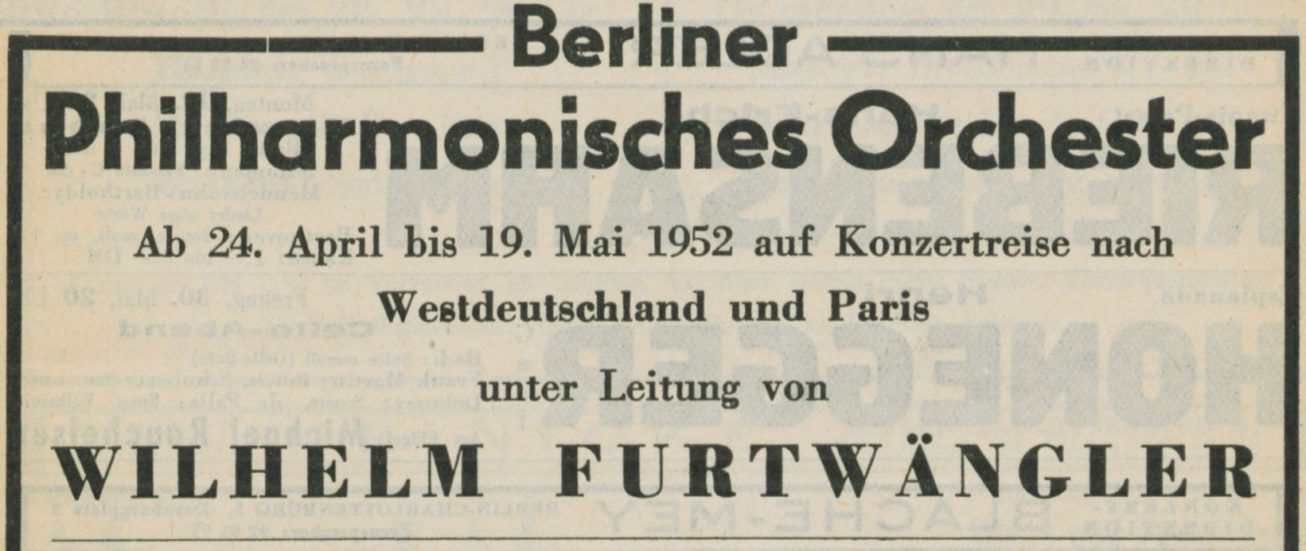

Avec le Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) de retour d’une tournée qui s’est déroulée entre le 24 avril et le 19 mai 1952, ils ont joué ce Concerto au Titania Palast de Berlin le 24 mai avant de l’enregistrer les 25 et 26 à la Jesus-Christus Kirche, salle utilisée habituellement par la Deutsche Grammophon et la RIAS.

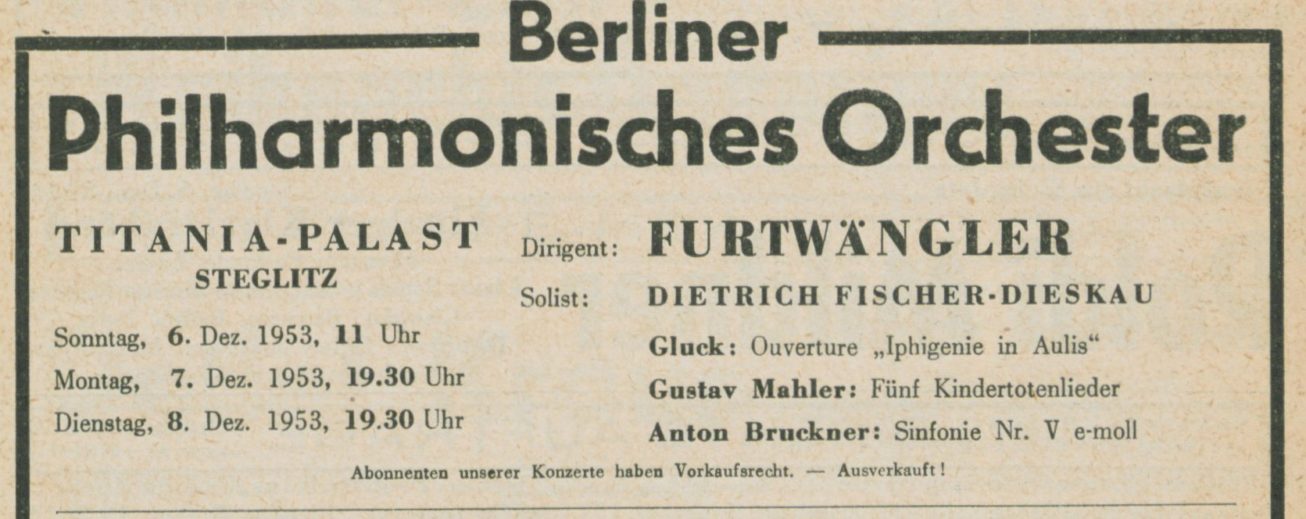

C’était la première fois qu’après la guerre EMI enregistrait Furtwängler à Berlin. Il y eut ensuite un autre enregistrement berlinois, à savoir l’Ouverture de ‘Leonore II’ de Beethoven les 4 et 5 avril 1954 à la Musikhochschule, avec cette fois une équipe d’enregistrement allemande (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), peut-être un test annonciateur d’un changement de politique discographique qui n’a malheureusement pas pu se concrétiser en raison du décès du chef d’orchestre. On peut penser en effet qu’EMI aurait souhaité enregistrer l’année suivante avec Furtwängler et le BPO les Kindertotenlieder de Mahler avec Fischer-Dieskau (l’œuvre a été jouée à Berlin en décembre 1953, et un enregistrement à Londres en mars 1954 avec le Philharmonia a été annulé) ainsi que le Deutsches Requiem de Brahms avec Grümmer et Fischer-Dieskau, deux projets qui ont été confiés in fine à la direction de Rudolf Kempe.

Menuhin and Furtwängler performed Mendelssohn’s Concerto Op.64 together for the first time on 29 September 1949 at London’s Royal Albert Hall with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With the Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) on their return from a tour that lasted from 24 April to 19 May 1952, they played this Concerto at the Titania Palast in Berlin on 24 May before recording it on 25 and 26 May at the Jesus-Christus Kirche, a venue known as being used by Deutsche Grammophon and RIAS.

It was the first time after the war that EMI recorded Furtwängler in Berlin. There was later another recording in Berlin, Beethoven’s Overture ‘Leonore II’ on April 4 and 5 1954 at the Musikhochschule, this time with a German recording team (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), maybe a test which heralded a change in recording policy that unfortunately could not materialise due to the conductor’s death. Indeed, one might think that EMI would have liked to record the following year with Furtwängler and the BPO Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with Fischer-Dieskau (the work was performed in Berlin in December 1953, and a recording in London in March 1954 with the Philharmonia had been cancelled) as well as Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem with Grümmer and Fischer-Dieskau, two projects that were ultimately entrusted to Rudolf Kempe.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

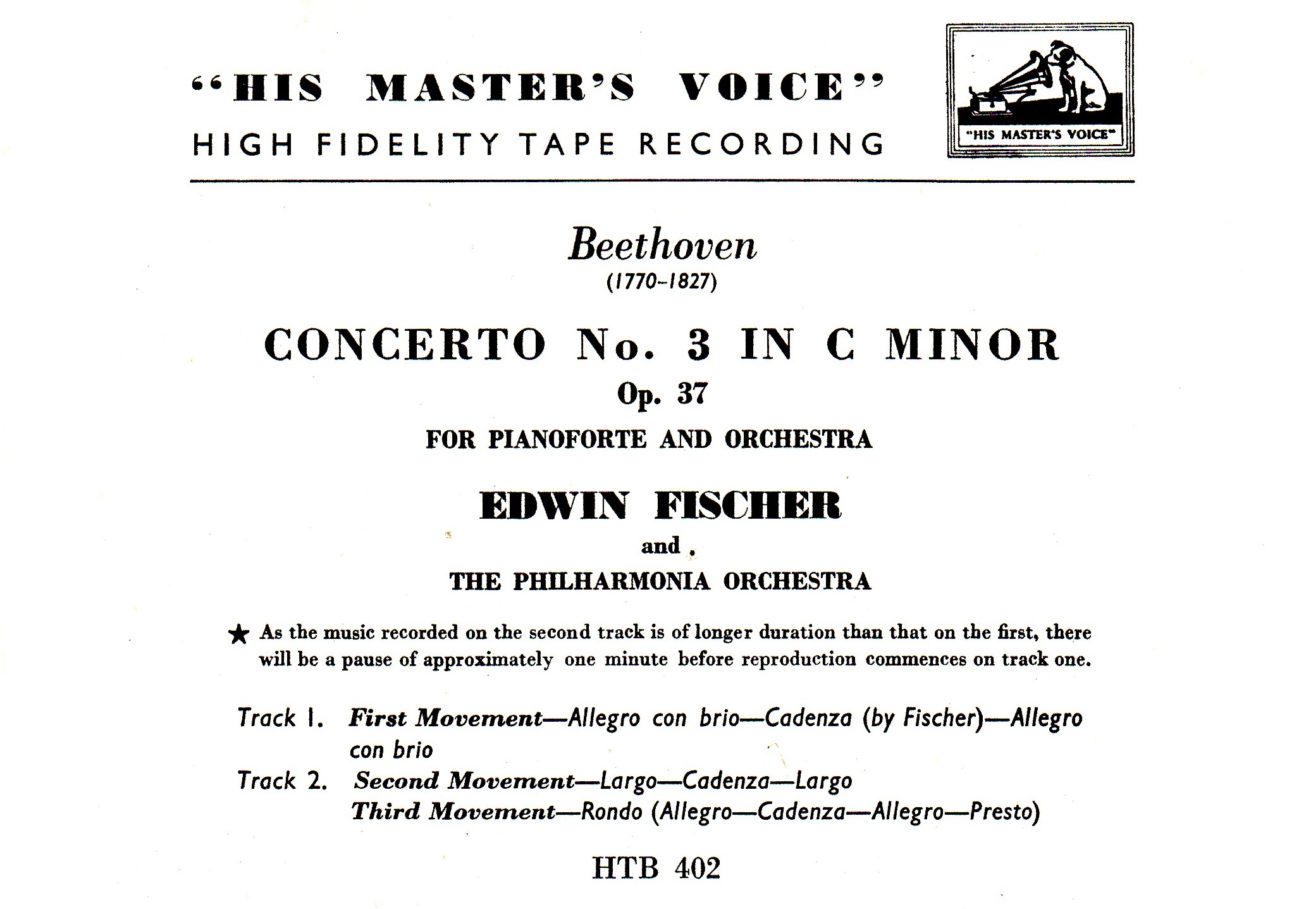

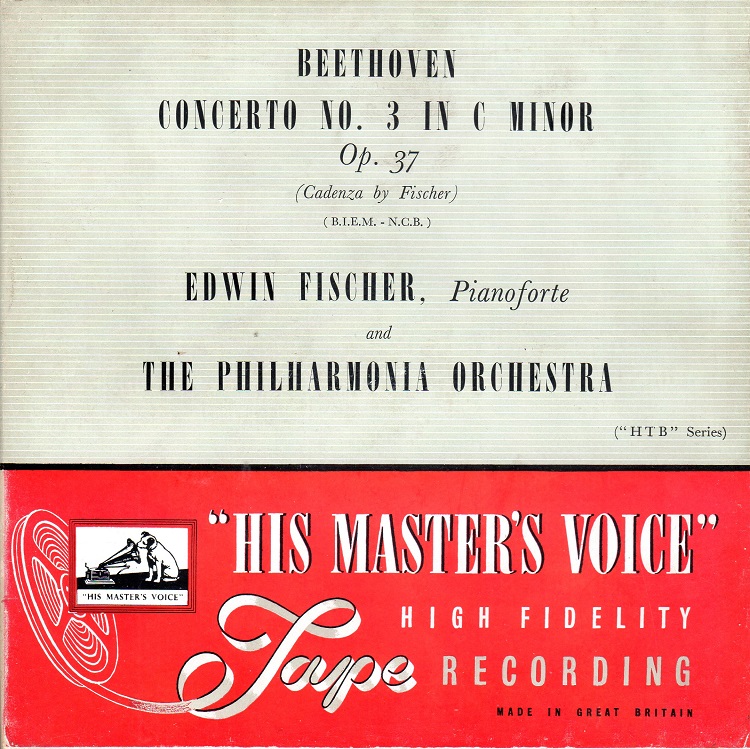

Fischer – Philharmonia Orchestra – Beethoven Concerto n°3 Op. 37

London Kingsway Hall – 7 & 14 mai 1954

Prod: Walter Jellinek & Alec Robertson – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTB 402

Nous vous avons déjà proposé cet enregistrement à partir de la même source. En voici le lien:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

La bande étant selon le standard CCIR, il a fallu tenir compte de la différence entre les courbes d’égalisation de la bande (CCIR) et le magnétophone (NAB) sur laquelle elle était lue. A l’époque, cette égalisation n’a pu être faite que de manière approximative et le son obtenu accentuait les duretés de la prise de son, surtout sur l’orchestre. Avec une meilleure égalisation, le son est maintenant plus musical, sans que l’on perde pour autant les détails de l’interprétation.

We have already offered you this recording from the same source. Here is the link:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

As the tape was in the CCIR standard, it was necessary to take into account the difference between the equalisation curves of the tape (CCIR) and of the tape recorder (NAB) on which it was played. At the time, this equalisation could only be done approximately and the sound obtained accentuated the harshness of the recording, especially on the orchestra. With better equalisation, the sound is now more musical, without losing any of the details of the performance.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

Maestro Editions qui a déjà publié le concert dirigé par Edwin Fischer lors du Festival de Strasbourg 1953, nous offre des inédits d’importance provenant cette fois du Festival de Salzbourg, où Fischer dirige les Wiener Philharmoniker. Il s’agit de la totalité du concert du 30 juillet 1951 (Mozart Concerto n°24 K.491, Haydn Symphonie n°104 et Beethoven Concerto n°1 Op.15) et du seul enregistrement qui subsiste du concert du 1er août 1949 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58).

Pour plus de détails, suivez ce lien:

Maestro Editions, which has already published the concert conducted by Edwin Fischer at the 1953 Strasbourg Festival, is now offering us some important previously unreleased material from the Salzburg Festival, where Fischer conducts the Wiener Philharmoniker. It is comprised of the entire concert of 30 July 1951 (Mozart Concerto No. 24 K.491, Haydn Symphony No. 104 and Beethoven Concerto No. 1 Op.15) and of the only surviving recording of the concert of 1 August 1949 (Beethoven Concerto No. 4 Op.58).

For more information, follow this link:

Charles Munch Ravel

Orchestre National de la RTF (ON)

Tombeau de Couperin

Festival de Besançon – Théâtre Municipal 2 Septembre 1954

______

Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)

Ma Mère l’Oye (suite)

Boston Symphony Hall January 31, 1958

La Valse

Boston Symphony Hall December 6, 1957

La Valse Répétition/Rehearsal

Boston Symphony Hall February 12, 1950

______

Bonus: Charles Munch – Interview (1964)

Source Bande/Tape : 2 pistes/19 cm/s / 2 tracks 7.5 ips MONO

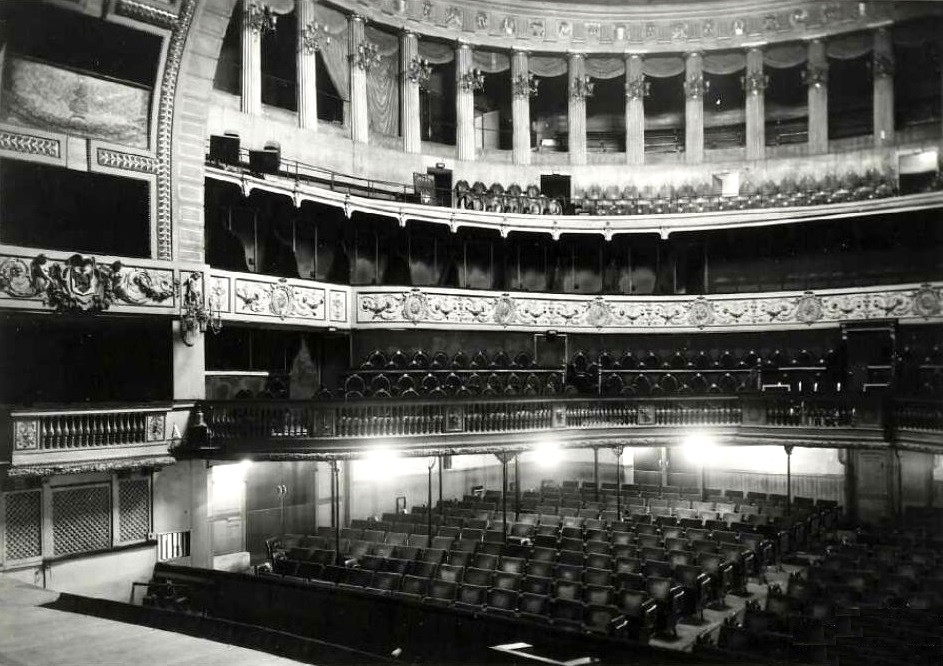

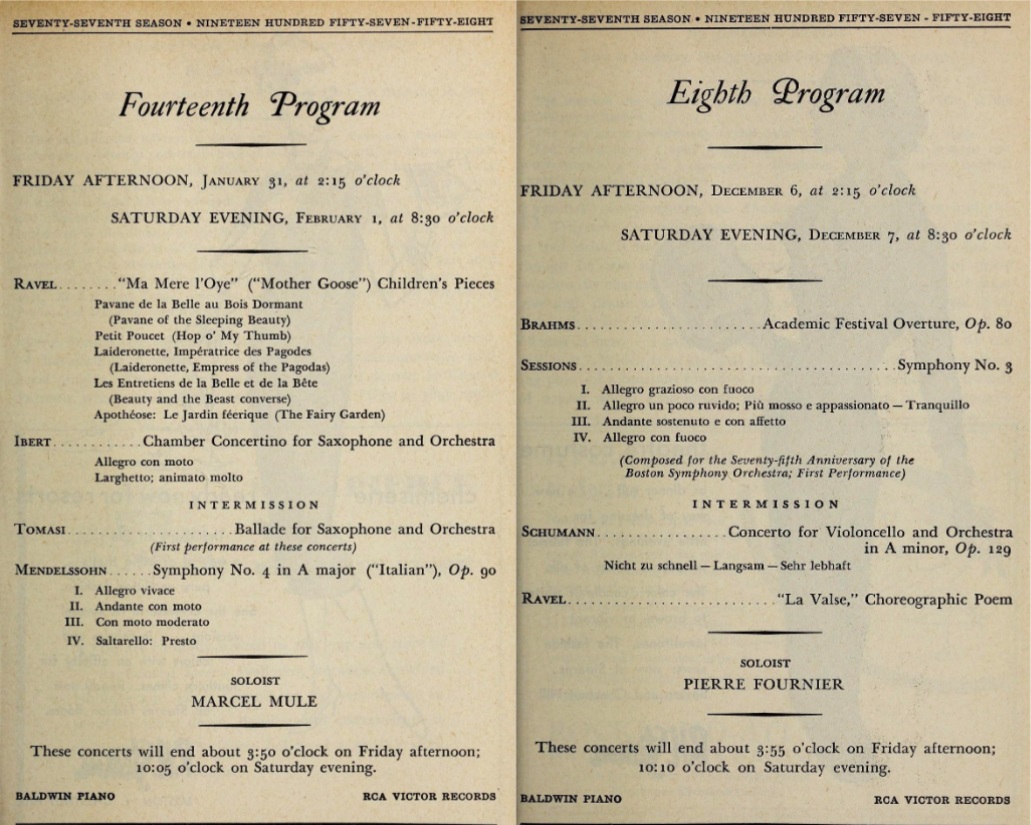

Charles Munch a dirigé 24 fois le ‘Tombeau de Couperin avec le BSO entre 1950 et 1961, mais il n’en a pas laissé de version discographique. On en connaît un enregistrement public du 17 octobre 1953 avec le BSO, publié par WHRA, dans lequel les variations de tempo peuvent paraître exagérées. Cette version avec l’Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF), souvent appelé ‘l’ON’ provient du concert d’ouverture du Septième Festival de Besançon 1954, donné au Théâtre Municipal. On possède peu d’enregistrements réalisés dans ce Théâtre conçu par l’architecte Claude-Nicolas Ledoux – il a été inauguré en 1784 -et renommé pour son acoustique. En effet, il a été entièrement détruit par un incendie en avril 1958, et s’il a été reconstruit, ce fut très rapidement pour assurer une continuité.

A Boston, Munch n’a donné que 6 fois la Suite de ‘Ma Mère l’Oye’, en janvier-février 1958, mais il en a cependant réalisé un enregistrement discographique le 19 février.

La Valse a été jouée 56 fois par Munch et le BSO entre 1950 et 1966, et avec cet orchestre, il l’a enregistré trois fois pour le disque (11 avril 1950, 5 décembre 1955 et 26 mars 1962). L’extrait de la répétition de 1950 nous montre quel niveau d’intensité Munch pouvait atteindre. L’enregistrement de concert du 6 décembre 1957 est semble-t-il inédit.

Munch Festival de Strasbourg 1954

Charles Munch conducted the ‘Tombeau de Couperin’ 24 times with the BSO between 1950 and 1961, but he left no commercial recording of it. We know of a public recording of October 17, 1953 with the BSO, published by WHRA, in which the tempo variations may seem exaggerated. This version with the Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (RTF), often called ‘l’ON’, comes from the opening concert of the Seventh Besançon Festival 1954, given at the Théâtre Municipal. Few recordings made in this Theatre, designed by architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux – it was inaugurated in 1784 – and renowned for its acoustics, have survived. In fact, it was completely destroyed by fire in April 1958, and if it was rebuilt, it was very quickly to ensure continuity.

In Boston, Munch performed the Suite from ‘Ma Mère l’Oye’ only 6 times, in January-February 1958, although he did make a commercial recording of it on February 19.

‘la Valse’ was performed 56 times by Munch and the BSO between 1950 and 1966, and with this orchestra he recorded it three times for disc (April 11, 1950, December 5, 1955 and March 26, 1962). The excerpt from the 1950 rehearsal shows us the level of intensity Munch could achieve. The concert recording of December 6, 1957 appears to be unpublished.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

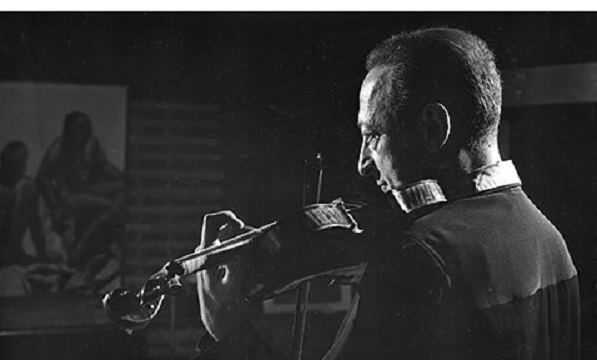

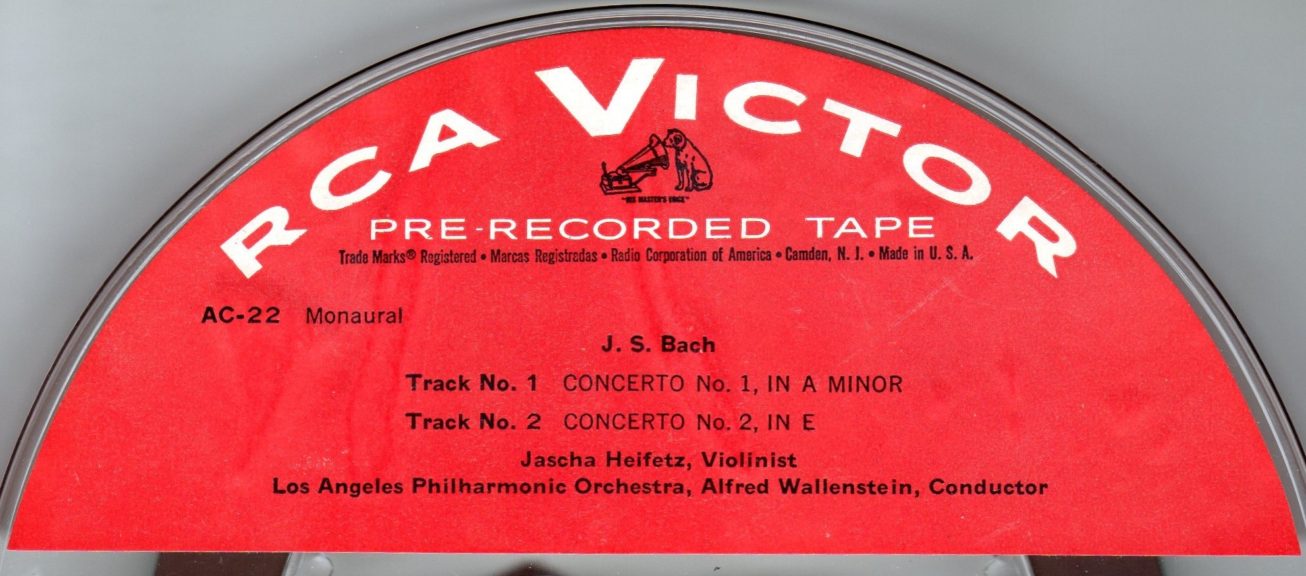

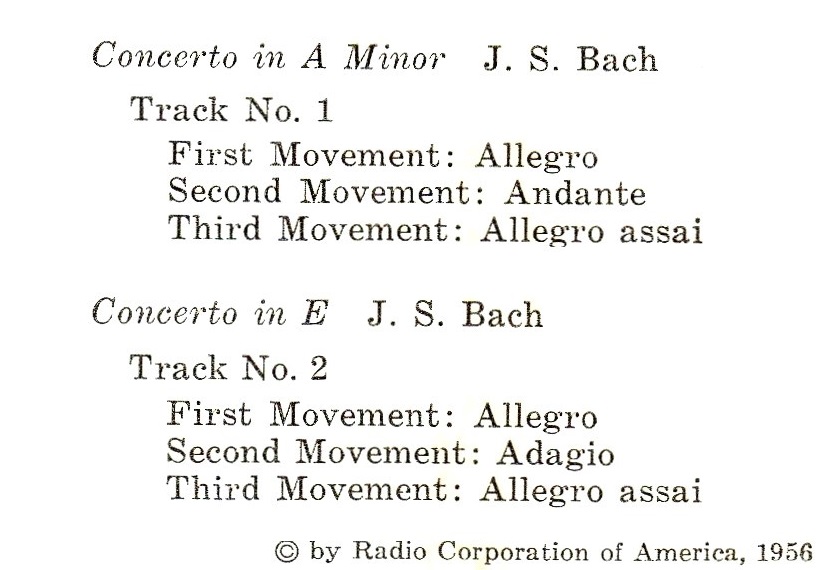

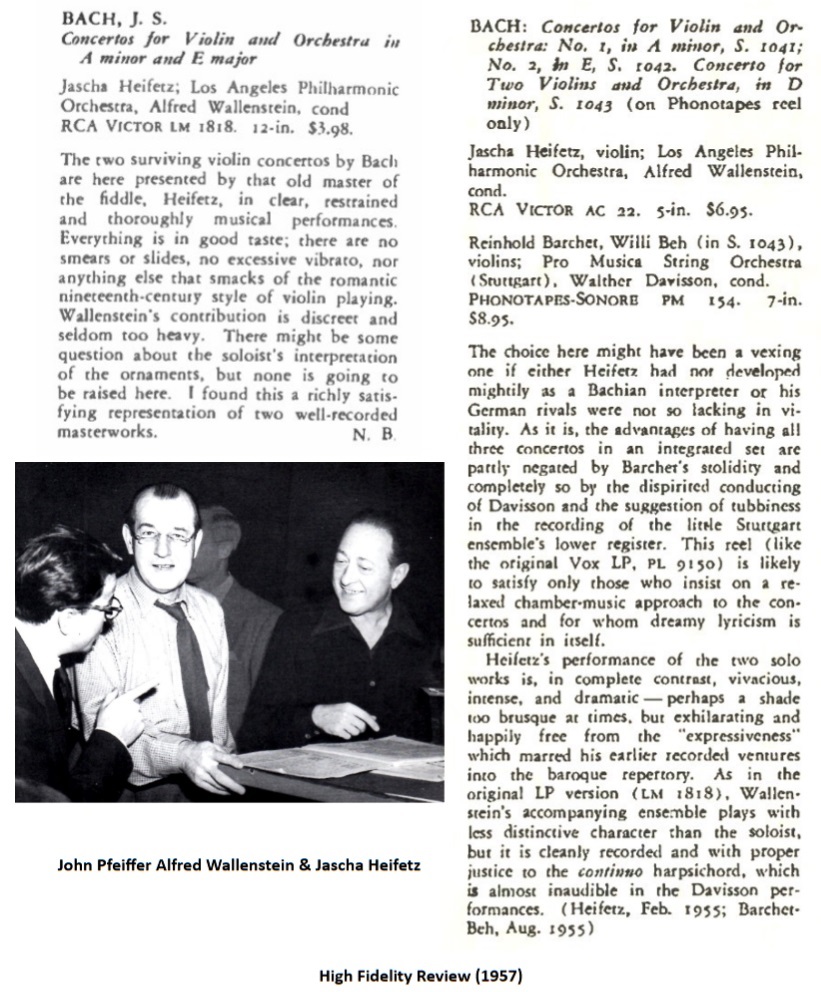

Jascha Heifetz – Alfred Wallenstein Los Angeles Philharmonic (LAPO)

Bach Concertos BWV 1041 & 1042

Hollywood – Republic Studios (Soundstage 9) – December 6, 1953

Source Bande/Tape RCA AC-22: 2 pistes/19 cm/s / 2 tracks 7.5 ips MONO

Heifetz n’a enregistré qu’une seule fois ces concertos pour le disque, sans même refaire de nouvelles versions pour la stéréo, que RCA a commencé à utiliser régulièrement pour ses enregistrements à peine quelques mois plus tard, à partir de mars 1954. Ici, le style, très dynamique, reste plutôt classique et l’effectif orchestral est relativement peu nombreux, ce qui nous éloigne heureusement des grands orchestres avec un plein effectif d’instrumentistes à cordes que l’on trouvait souvent à l’époque pour jouer ces œuvres.

Alfred Wallenstein (1898-1983) a été le violoncelle solo des orchestres de San Francisco, Los Angeles, et Chicago avant que Toscanini l’appelle en 1929 à ce même poste au NYPO, et ensuite l’encourage à entamer une carrière de chef d’orchestre. En 1943, il a succédé à Otto Klemperer à la tête du L APO, poste qu’il a conservé jusqu’en 1956, son successeur étant Eduard van Beinum.

Heifetz made only one commercial version of these concertos, without even making new versions for stereo, which RCA started to use regularly for its recordings only a few months later, in March 1954. Here, the highly dynamic style remains rather classical, and the orchestra is relatively limited in size, which fortunately takes us away from the large orchestras with a full body of strings, often used at the time to play these works.

Alfred Wallenstein (1898-1983) was principal cellist of the San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago orchestras before Toscanini called him in 1929 to the same position at the NYPO, and then encouraged him to start a conducting career. In 1943, he succeeded Otto Klemperer as head of the LAPO, a post he held until 1956, his successor being Eduard van Beinum.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment