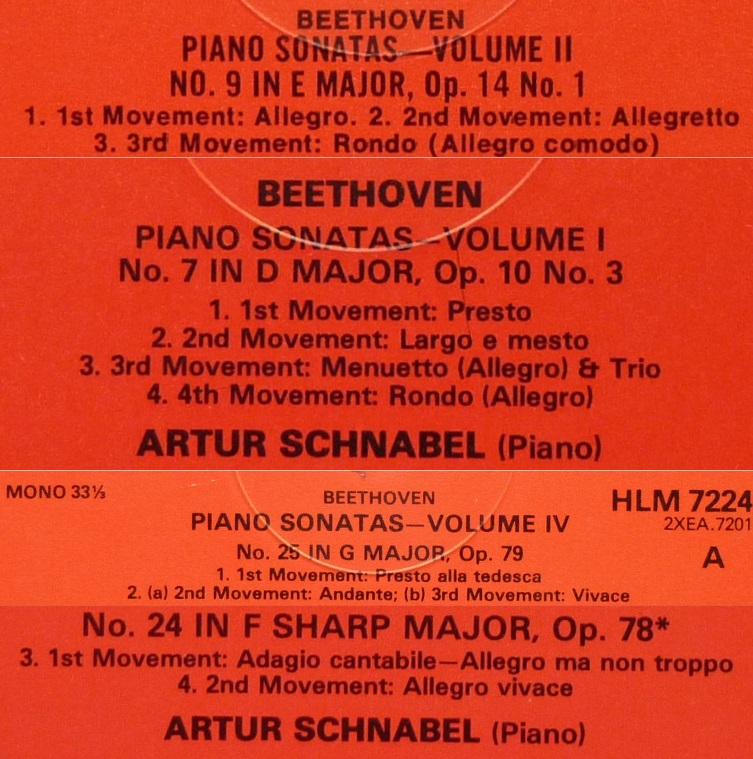

Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates- VII/VII – Sonates n°9 Op.14 n°1 – n°7 Op.10 n°3 – n°25 Op.79 – n°24 Op.78 – n°32 Op.111

Sonate n°9 Op.14 n°1: 25 Mars 1932

Sonate n°7 Op.10 n°3: 12 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°25 Op.79: 15 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°24 Op.78: 21 Mars 1932

Sonate n°32 Op.111: 21 Janvier, 21 & 22 Mars, 7 Mai 1932

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le septième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comprenait les cinq sonates ci-dessus, les deux premières étant, comme pour les autres récitals, jouées avant l’entracte.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le septième récital, donné le 26 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, a eu lieu au moment où, autre événement de la saison new-yorkaise, Arturo Toscanini poursuivait avec Rudolf Serkin la série de ses concerts d’adieu en tant que chef titulaire du New York Philharmonic. L’interprétation par Schnabel de la sonate n°24 Op.78, dédiée à Therese von Brunswick, a atteint un niveau tel qu’elle a presque ‘ volé la vedette’ à l’Opus 111! (voir la critique ci-dessous). Une idée de génie de la part de Schnabel que d’associer ces deux œuvres pour terminer son intégrale, ce que l’on peut apprécier d’autant plus qu’elles ont été superbement enregistrées ensemble en 1932, et que l’interprétation de l’Arietta conclusive de l’Opus 111 y est vraiment extraordinaire.

Pour le critique: ‘les deux premières sonates de la liste, celle en mi majeur Op.14 n°1 (n°9) et celle en ré majeur Op.10 n°3 (n°7), toutes deux de 1797, quand le compositeur n’avait pas encore atteint la trentaine, représentaient la phase antérieure de son développement. Les sonates en sol majeur Op.79 (n°25) et en fa dièse majeur Op.78 (n°24) servaient à illustrer la maîtrise qui était celle de Beethoven en 1809, alors que l’Opus 111 (n°32) a été réservée pour conclure le programme et toute la série, non seulement parce qu’il s’agissait de la dernière œuvre de Beethoven sous cette forme pour le piano, mais aussi parce qu’elle reste, à bien des égards, la plus grande de toutes les sonates. Cet ultime récital a une fois de plus mis en avant, sans nul doute, l’étonnante musicalité de Mr. Schnabel, qui est tellement évidente à tout instant dans ses interprétations que même le plus néophyte des auditeurs doit en percevoir quelque chose, alors qu’elle ne cesse de stupéfier le public des connaisseurs…… Avec toute l’appréciation qui était due à ce que Mr. Schnabel a accompli hier soir dans l’opus 111, c’est dans le superbe déroulement de la relativement négligée sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) que résidait sa prestation sa plus étonnante et la plus significative. Ici, Mr. Schnabel a revêtu le manteau impérial à la fois de pianiste et d’interprète. Peu de ceux qui ont entendu l’interprétation de la sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) risqueront de l’oublier, eu égard à son effet d’ensemble, ou bien par rapport à ses détails saillants. La sonate n’est pas entendue souvent, sans doute pour la raison que peu de pianistes la trouvent soit gratifiante, soit facile à unifier pour faire ressortir une relation positive entre ses deux mouvements. La perspicacité de Mr. Schnabel et sa compréhension de ses réelles possibilités ont donné une lecture qui a du re-créer l’œuvre pour chaque musicien dans la salle. Dans l’Allegro qui ouvrait l’œuvre et qui pour une fois n’était pas pris trop rapidement, il y avait des passages d’un charme sonore exceptionnel. Il en était de même des mesures de transition entre les deux sujets principaux pour lesquels les mélodies respectives à la main droite et à la main gauche étaient exquisement modelées sur un fond scintillant de doubles croches dans les accords brisés supérieurs qui était un ravissement pour l’oreille. Mais c’est dans le final que Mr. Schnabel a atteint son zénith à cette occasion. Il serait impossible d’exagérer la magie de ce mouvement, dans lequel la plupart des pianistes pataugent désespérément dans un marais de notes survolées sans signification aucune. Mr. Schnabel, avec sa relecture de cette division de l’œuvre, a enfin projeté une lumière réelle sur sa signification. Et quelle joie cela a été de l’entendre interprétée de sorte que la figuration élaborée qui relie les mouvements entre eux a pris forme et proportion sous les doigts experts du pianiste, d’où elle émergeait comme un moment brillant de bravoure de la plus haute espèce. La place manque pour discuter de la restitution de l’Op.111 (n°32), qui était carrément dramatique dans le premier mouvement et remarquablement originale à certains moments du dernier. Dans l’Arietta, le thème a été énoncé avec le son chantant, la tendresse et la simplicité qu’il exige, mais reçoit rarement. Mais particulièrement admirable était l’atmosphère mystérieuse de la quatrième variation et la délicatesse des figures murmurées de la cinquième variation. C’est avec ce caractère suprême que le pianiste a terminé son magnifique hommage au génie de Beethoven.’

The seventh program for the complete 32 Sonates of Beethoven by Artur Schnabel was comprised of the five above cited sonatas, the first two being, as for the other recitals, played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The seventh recital, given on 26 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, took place when, yet another event of the New York season, Arturo Toscanini pursued with Rudolf Serkin the series of his farewell concerts as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Schnabel’s performance of the sonata n°24 Op.78, dedicated to Therese von Brunswick, was of such a level that it almost ‘stole the show’ to Opus 111! (see below). Indeed, it was a stroke of genius by Schnabel to couple these two works to end his ‘marathon’, which we can appreciate all the more since they have been masterfuly recorded together in 1932, and since the recorded interpretation of the Arietta ending Opus 111 is really extraordinary.

For the critic:’ the first two sonatas on the list, that in E major, Op.14 n°1 (n°9), and that in D major, Op.10 n°3 (n°7), both stemming from 1797, when the composer was still in his twenties, represented the earlier phase of development. The sonatas in G major Op.79 (n°25) and in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) served to illustrate the mastery that was Beethoven’s in 1809, when these were written, while the Op.111 (n°32) was reserved to end the program and the series, not merely because it was Beethoven’s last work in the form for the piano, but because it remains in many respects the greatest of all sonatas. Ths culminating recital of the seven, once again published in no uncertain manner Mr. Schnabel’s astounding musicianship, which is so evident at every moment in his performances that the veriest tyro among his listeners must sense something of it, while it never ceases to amaze the connoisseurs in the audience…. With all due appreciation of what Mr. Schnabel accomplished in the Op.111 last night, his most startling and significant playing was heard in his superb unfolding of the rather neglected sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24). Here, Mr. Schnabel wore the imperial mantle both as pianist and as interpreter. Few who heard the interpretation of the sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) are likely to forget it, either in respect to its effect as a whole, or in regard to its salient details. The sonata is not often heard, for the reason, undoubtly, that few pianists find it either grateful, or easy to unify by bringing out a positive relation between its two movements. Mr. Schnabel’s insight and his understanding of its real possibilities, resulted in a reading which must have re-created the work for every musician in the house. There were passages in the opening Allegro (which, for once, was not taken too rapidly, as it usually is) of exceptional tonal charm. Such were the transitional measures between the two main subjects, where the respective melodies in the right and left hand were exquisitely molded against a glittering ripple of sixteenths in the upper broken chords that was fairly ravishing to the ear. But it was in the Finale that Mr. Schnabel reached his zenith on this occasion. It would be impossible to overstate his wizardy in this movement, where most pianists flounder hopelessly in a morass of flying notes meaning nothing. Mr. Schnabel, in his re-editing of this division of the work, has at last thrown some real light on its meaning. And what a joy it was to have it performed so that the elaborate figuration that binds the movements together took on shape and proportion under the pianist’s knowing fingers, whence it emerged as a coruscating bit of bravura of the highest type. There is no space to go into a discussion of Mr. Schnabel’s rendition of the Opus 111, which was emphatically dramatic in the first movement and strikingly original in certain phases of the last. In the Arietta, the theme was stated with the singing tone, the tenderness and simplicity it demands and seldom receives. But especially admirable were the mysterious atmosphere created in the fourth variation and the ineffable delicacy of the purling figures of the fifth variant. By art of this superlative nature the pianist completed his splendid tribute to Beethoven’s genius.’

____________

5 réponses sur « Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates- VII/VII – Sonates n°9 Op.14 n°1 – n°7 Op.10 n°3 – n°25 Op.79 – n°24 Op.78 – n°32 Op.111 »

HD/Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZgPBzZ8P3dxoA7Be7l6QSipPVW4HLS69Fy

Format CD (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZxPBzZ3mLo0xbl8t0E1BL6I5FqV7vTnWNX

Thanks a zillion for these superb transfers of Schnabel’s classic Beethoven sonatas recordings; they are the best I have ever heard.

Received with great thanks!

Thanks also from the USA for this majestic effort!

Thanks as always for your comments!