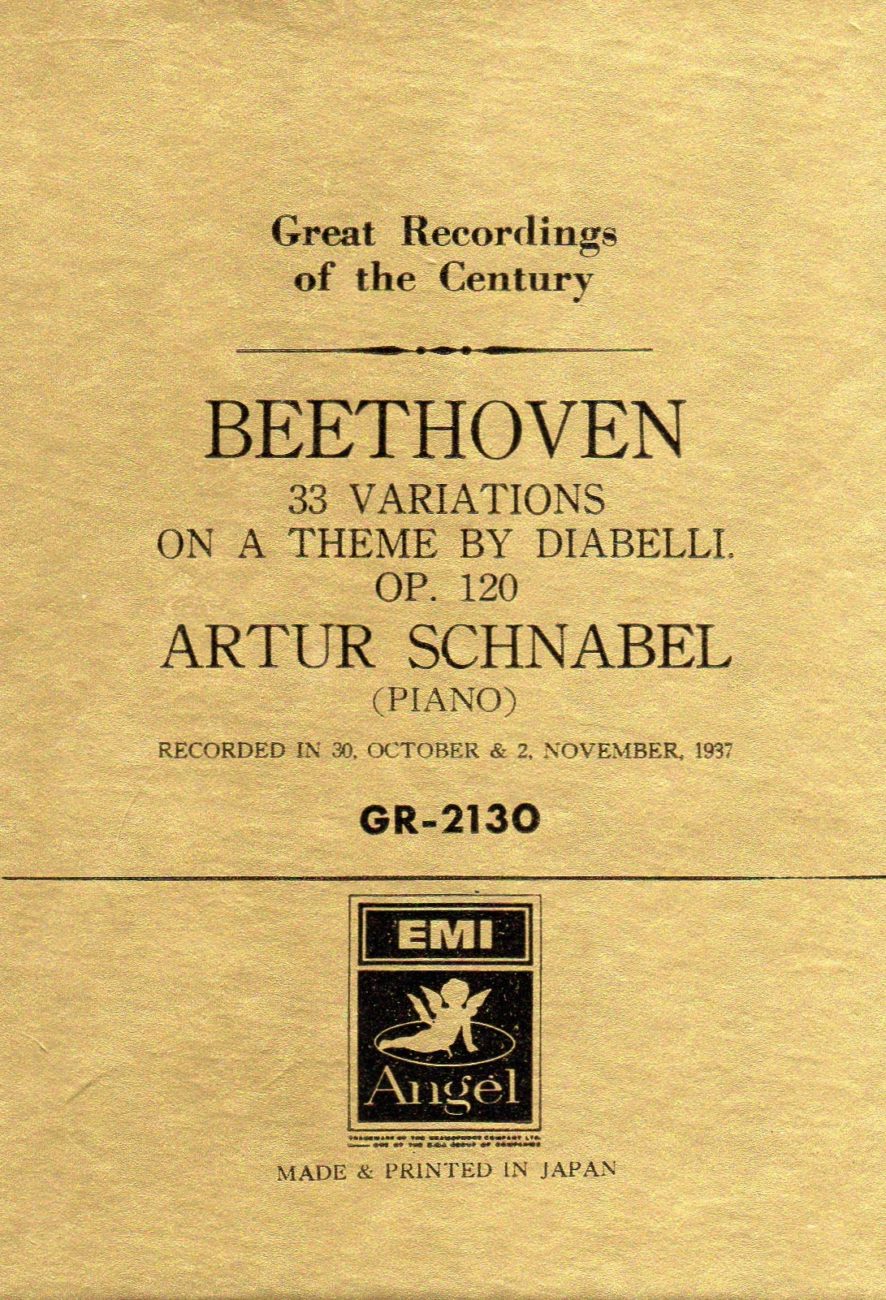

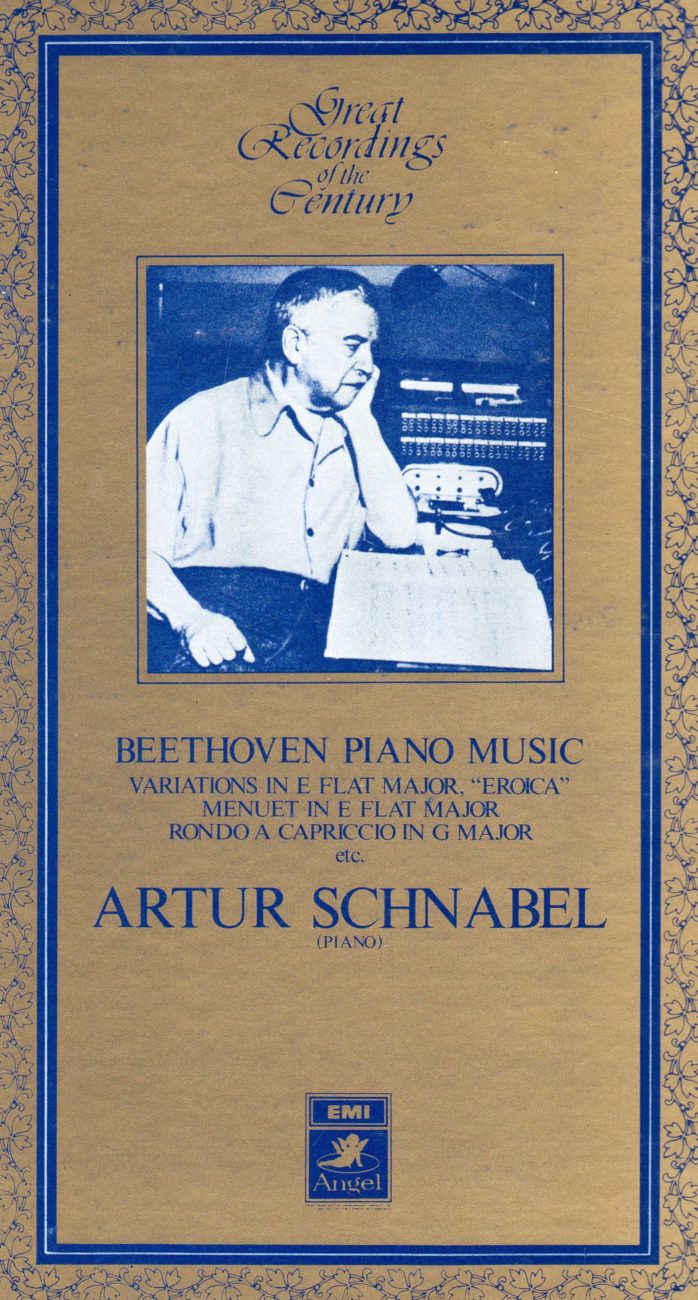

Schnabel – III – Beethoven: Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 & « Eroïca » Op.35

Artur Schnabel, piano Bechstein – London Abbey Road Studio n°3

Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 October 30 & November 2, 1937 (Bechstein n°560)

Variations « Eroïca » Op.35 – November, 9 1938

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Les deux microsillons EMI-Toshiba qui ont servi à cette ré-édition proviennent de reports effectués par Anthony Griffith. Réalisés à partir de pressages vinyles des matrices 78t. d’origine, ils présentent la particularité d’être peu ou pas filtrés et ainsi de nous offrir toute la palette sonore du pianiste, car la technique d’Artur Schnabel, souvent critiquée par ailleurs à cause de ses fausses notes, comportait une gamme très étendue de nuances et de gradations de toucher, de la douceur à la puissance.

La richesse d’écriture de ces variations de Beethoven permet fort heureusement à Schnabel de déployer tout l’éventail de ses qualités pianistiques.

Au cours d’une série de conférences données en 1945 à l’Université de Chicago, Schnabel a eu l’occasion, en réponse à des questions posées posées par les étudiants, d’expliquer quelle avait été sa conception du choix des pianos et de la production du son avant qu’il ne se décide à passer du Bechstein au Steinway à son arrivée aux États-Unis en 1939:

« Je dirais que la qualité qui distingue le piano de tous les autres instruments, est sa neutralité. Sur un piano, un son unique ne peut être beau; c’est la combinaison et la proportion des sons qui apporte la beauté.

Il est nécessaire de produire au moins deux ou trois sons pour donner une impression de sensualité ou pour donner à l’oreille une sensation de musique, alors que presque tous les autres instruments (sauf les instruments à percussion) ou la voix peuvent vous donner un plaisir des sens même avec un seul son. Autour de 1910, on trouvait très ‘moderne’ de dire que le piano était un instrument à percussion et que vous pouviez tout jouer staccato. Stravinsky a beaucoup fait pour la promotion de ces idées de même que de nombreux professeurs de piano, et il y avait même un livre sur ce sujet.

Une fois, un musicien m’a dit – je croyais qu’il plaisantait- que frapper le clavier avec le bout d’un parapluie ou avec le doigt ne faisait pas la moindre différence quant à la sonorité produite. C’était aussi imprimé dans ce livre – et ce n’était pas non plus une plaisanterie. Bien sûr, ça n’a aucun sens, car quiconque veut faire de la musique sait très bien tout ce qu’il peut faire avec les doigts sur le piano.

Il peut produire toutes sortes de sons: pas seulement plus ou moins forts, ou plus ou moins longs, mais aussi différentes qualités. Sur un piano, il est possible d’imiter, par exemple, le son d’un hautbois, d’un violoncelle ou d’un cor. Mais il n’est pas possible d’imiter le son d’un hautbois sur une flûte, ou d’une clarinette sur un violon; ces autres instruments conservent toujours leurs caractéristiques propres. C’est pour ça que je dis que la particularité du piano est, dans son essence, d’être le plus neutre des instruments.

Le piano Bechstein satisfaisait mieux à cette exigence de neutralité que n’importe quel autre piano que j’ai connu. Vous pouviez pratiquement tout faire sur ce piano. Le Steinway – ou plutôt le Steinway d’il y a vingt ans, car il a pas mal changé depuis – était un piano qui voulait toujours montrer quelque chose. Vous voyez, il avait beaucoup trop de personnalité propre.

Au début, quand je voulais produire quelque chose comme, disons, la voix d’un oiseau sur un Steinway, le piano sonnait toujours pour moi comme la voix d’un ténor au lieu d’un oiseau. Pendant de nombreuses années, j’ai eu le sentiment que le piano Steinway ne m’aimait pas. Une idée absurde, mais j’avais ce sentiment. Le piano Bechstein me permettait de produire des effets qui n’étaient pas possibles sur un Steinway. Le son du Steinway vibrait beaucoup plus: il a un double actionnement. Quand vous pressez très légèrement et lentement la touche d’un Steinway, elle s’arrête avant le bas, et elle a besoin d’une certaine pression, d’une seconde pression pour achever sa course vers le bas. Maintenant, j’y suis tellement habitué que cela ne m’irrite plus du tout. Au début, cependant, cela me gênait énormément: en effet, pour produire un fortissimo, vous pouvez jouer légèrement, mais si vous voulez jouer pianissimo, vous avez besoin d’utiliser beaucoup de poids sinon la touche ne descend pas. Cela semble assurément pervers. »

Both EMI-Toshiba LPs used for this re-issue come from transfers made by Anthony Griffith. Dubbed from vinyl pressings of the 78rpm metal parts, they have the particularity of having been unfiltered, or very little, and thus to offer all the pianist’s sound palette, since Artur Schnabel’s technique, otherwise often criticized because of his wrong notes, was comprised of a very extended range of nuances and touch, from softness to power.

The richness of writing of these variations by Beethoven happily allows Schnabel to show the whole spectrum of his pianistic qualities.

During a series of conferences given in 1945 at the University of Chicago, Schnabel, answering questions asked by students, had the opportunity of explaining what had been his views on the choice of pianos and on the production of sound before he decided to switch from Bechstein to Steinway when he arrived in the U-S in 1939:

« I would say that the quality which distinguishes the piano from all other instruments, is its neutrality. On a piano a single tone cannot be beautiful; it is the combination and proportion of tones which bring beauty.

You are forced to produce at least two or three tones in order to create a sensuous impression or to give a sensation of music to the ear, while almost all other instruments (except percussion instruments) or the voice can give you a sensuous pleasure even from a single tone. Around 1910 it was considered very ‘modern’ to say that the piano is a percussion instrument and that you could play everything staccato. Stravinsky did much towards promoting these ideas along with many piano teachers, and there was a book on the subject.

Once I was told by a musician—I hope he was joking—that it does not make the slightest difference for the sonority whether you strike or hit the keyboard with the tip of an umbrella or with a finger. That was also printed in that book—and not as a joke. Of course it is sheer nonsense, for everybody who wants music knows very well all that he can do with the fingers on the piano.

He can produce all kinds of tones: not only louder or softer, shorter or longer tones, but also different qualities. It is possible on a piano to imitate, for instance, the sound of an oboe, a ‘cello’, a French horn. But it is not possible to imitate the sound of an oboe on a flute, or a clarinet on a violin; these other instruments always retain their own characteristics. That is why I said that the distinction of the piano is in its being the most neutral instrument.

The Bechstein piano fulfilled this demand for neutrality better than any other piano I have known. You could do almost anything on that piano. The Steinway—or rather the Steinway of twenty years ago, for it has changed somewhat since that time—was a piano which always wanted to show something. You see, it had much too much of a personality of its own.

At first, when I wanted to produce something like, let me say, the voice of a bird on a Steinway, the piano always sounded to me like the voice of a tenor instead of a bird. For many years, I had the feeling that the Steinway piano did not like me. An absurd idea, but I had that feeling. The Bechstein piano enabled me to show effects not possible on a Steinway. The tone of the Steinway vibrated much more: it has a different action. When you push a Steinway key very lightly and slowly down, it will stop before it has reached the bottom and requires a certain pressure, a second pressure to go down all the way. This is the »double action ». By now I am so used to it that it hardly irritates me any more. At first, however, it disturbed me greatly: for in order to produce a « fortissimo » you can play lightly, but whenever you want to play « pianissimo » you have to use a great deal of weight as otherwise the key would not go down. It certainly seems perverse.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

3 réponses sur « Schnabel – III – Beethoven: Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 & « Eroïca » Op.35 »

HD/Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.com/publink/show?code=kZtkr5ZhXI3EIGW5q8iB2tALuXQchxp4sk0

Format CD (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.com/publink/show?code=kZNuVJZHBpBueiEADRQOdFgWInPkyeJ5esy

Thank You.

Congratulation to 1 year of the blog! Amazing work, very enjoyable. Thank You for this amazing place!