Étiquette : Artur Schnabel

Artur Schnabel, piano Bechstein – London Abbey Road Studio n°3

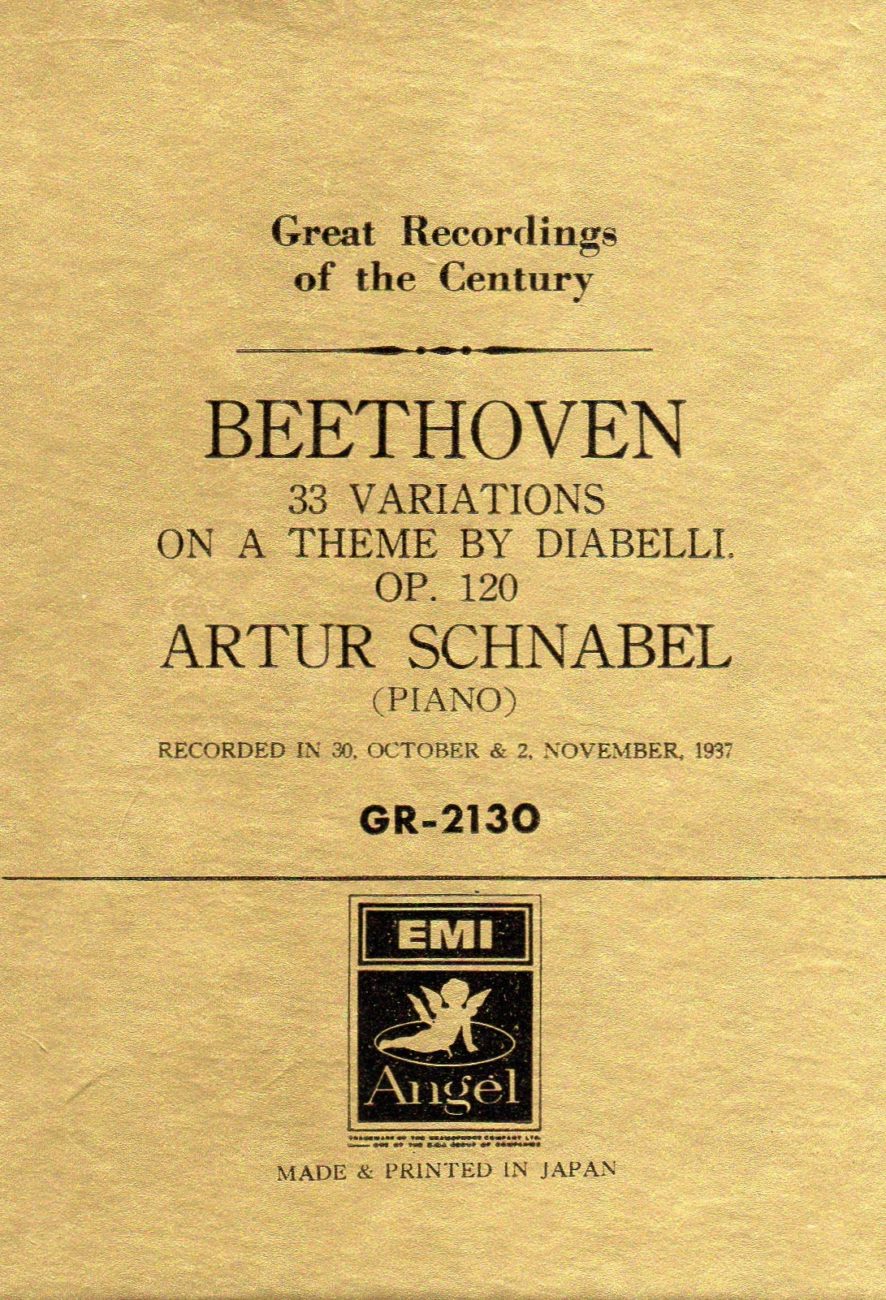

Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 October 30 & November 2, 1937 (Bechstein n°560)

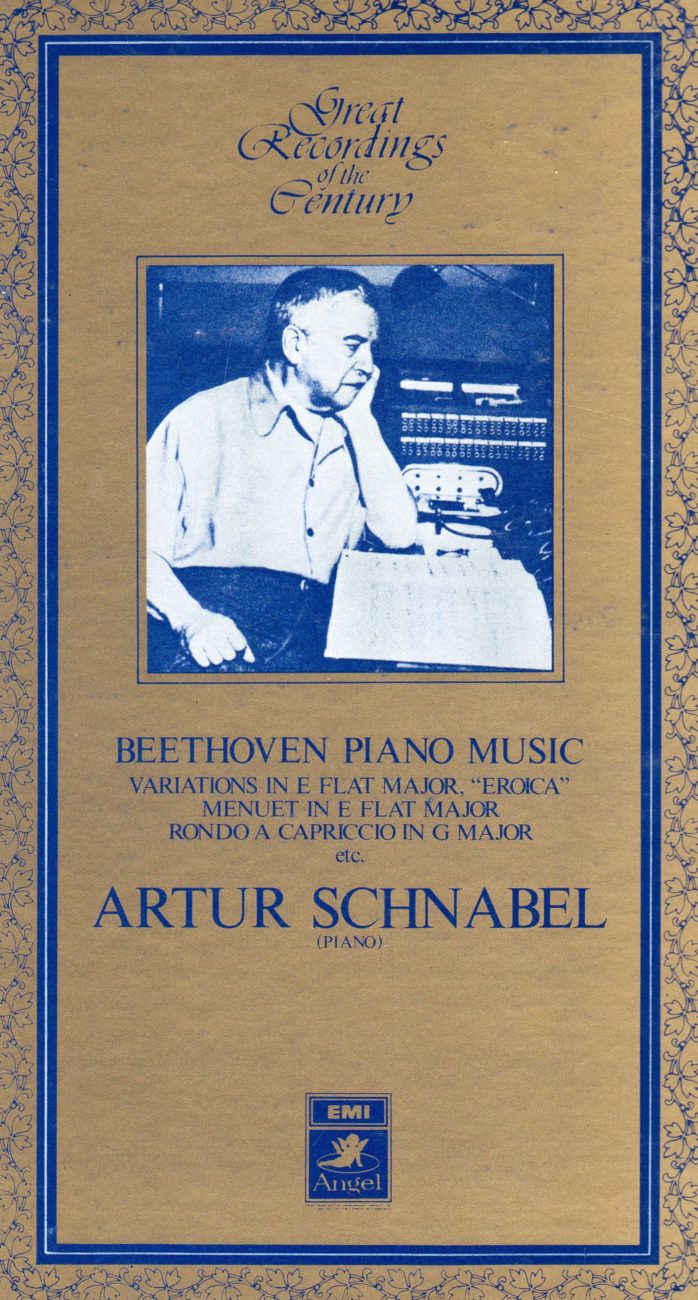

Variations « Eroïca » Op.35 – November, 9 1938

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Les deux microsillons EMI-Toshiba qui ont servi à cette ré-édition proviennent de reports effectués par Anthony Griffith. Réalisés à partir de pressages vinyles des matrices 78t. d’origine, ils présentent la particularité d’être peu ou pas filtrés et ainsi de nous offrir toute la palette sonore du pianiste, car la technique d’Artur Schnabel, souvent critiquée par ailleurs à cause de ses fausses notes, comportait une gamme très étendue de nuances et de gradations de toucher, de la douceur à la puissance.

La richesse d’écriture de ces variations de Beethoven permet fort heureusement à Schnabel de déployer tout l’éventail de ses qualités pianistiques.

Au cours d’une série de conférences données en 1945 à l’Université de Chicago, Schnabel a eu l’occasion, en réponse à des questions posées posées par les étudiants, d’expliquer quelle avait été sa conception du choix des pianos et de la production du son avant qu’il ne se décide à passer du Bechstein au Steinway à son arrivée aux États-Unis en 1939:

« Je dirais que la qualité qui distingue le piano de tous les autres instruments, est sa neutralité. Sur un piano, un son unique ne peut être beau; c’est la combinaison et la proportion des sons qui apporte la beauté.

Il est nécessaire de produire au moins deux ou trois sons pour donner une impression de sensualité ou pour donner à l’oreille une sensation de musique, alors que presque tous les autres instruments (sauf les instruments à percussion) ou la voix peuvent vous donner un plaisir des sens même avec un seul son. Autour de 1910, on trouvait très ‘moderne’ de dire que le piano était un instrument à percussion et que vous pouviez tout jouer staccato. Stravinsky a beaucoup fait pour la promotion de ces idées de même que de nombreux professeurs de piano, et il y avait même un livre sur ce sujet.

Une fois, un musicien m’a dit – je croyais qu’il plaisantait- que frapper le clavier avec le bout d’un parapluie ou avec le doigt ne faisait pas la moindre différence quant à la sonorité produite. C’était aussi imprimé dans ce livre – et ce n’était pas non plus une plaisanterie. Bien sûr, ça n’a aucun sens, car quiconque veut faire de la musique sait très bien tout ce qu’il peut faire avec les doigts sur le piano.

Il peut produire toutes sortes de sons: pas seulement plus ou moins forts, ou plus ou moins longs, mais aussi différentes qualités. Sur un piano, il est possible d’imiter, par exemple, le son d’un hautbois, d’un violoncelle ou d’un cor. Mais il n’est pas possible d’imiter le son d’un hautbois sur une flûte, ou d’une clarinette sur un violon; ces autres instruments conservent toujours leurs caractéristiques propres. C’est pour ça que je dis que la particularité du piano est, dans son essence, d’être le plus neutre des instruments.

Le piano Bechstein satisfaisait mieux à cette exigence de neutralité que n’importe quel autre piano que j’ai connu. Vous pouviez pratiquement tout faire sur ce piano. Le Steinway – ou plutôt le Steinway d’il y a vingt ans, car il a pas mal changé depuis – était un piano qui voulait toujours montrer quelque chose. Vous voyez, il avait beaucoup trop de personnalité propre.

Au début, quand je voulais produire quelque chose comme, disons, la voix d’un oiseau sur un Steinway, le piano sonnait toujours pour moi comme la voix d’un ténor au lieu d’un oiseau. Pendant de nombreuses années, j’ai eu le sentiment que le piano Steinway ne m’aimait pas. Une idée absurde, mais j’avais ce sentiment. Le piano Bechstein me permettait de produire des effets qui n’étaient pas possibles sur un Steinway. Le son du Steinway vibrait beaucoup plus: il a un double actionnement. Quand vous pressez très légèrement et lentement la touche d’un Steinway, elle s’arrête avant le bas, et elle a besoin d’une certaine pression, d’une seconde pression pour achever sa course vers le bas. Maintenant, j’y suis tellement habitué que cela ne m’irrite plus du tout. Au début, cependant, cela me gênait énormément: en effet, pour produire un fortissimo, vous pouvez jouer légèrement, mais si vous voulez jouer pianissimo, vous avez besoin d’utiliser beaucoup de poids sinon la touche ne descend pas. Cela semble assurément pervers. »

Both EMI-Toshiba LPs used for this re-issue come from transfers made by Anthony Griffith. Dubbed from vinyl pressings of the 78rpm metal parts, they have the particularity of having been unfiltered, or very little, and thus to offer all the pianist’s sound palette, since Artur Schnabel’s technique, otherwise often criticized because of his wrong notes, was comprised of a very extended range of nuances and touch, from softness to power.

The richness of writing of these variations by Beethoven happily allows Schnabel to show the whole spectrum of his pianistic qualities.

During a series of conferences given in 1945 at the University of Chicago, Schnabel, answering questions asked by students, had the opportunity of explaining what had been his views on the choice of pianos and on the production of sound before he decided to switch from Bechstein to Steinway when he arrived in the U-S in 1939:

« I would say that the quality which distinguishes the piano from all other instruments, is its neutrality. On a piano a single tone cannot be beautiful; it is the combination and proportion of tones which bring beauty.

You are forced to produce at least two or three tones in order to create a sensuous impression or to give a sensation of music to the ear, while almost all other instruments (except percussion instruments) or the voice can give you a sensuous pleasure even from a single tone. Around 1910 it was considered very ‘modern’ to say that the piano is a percussion instrument and that you could play everything staccato. Stravinsky did much towards promoting these ideas along with many piano teachers, and there was a book on the subject.

Once I was told by a musician—I hope he was joking—that it does not make the slightest difference for the sonority whether you strike or hit the keyboard with the tip of an umbrella or with a finger. That was also printed in that book—and not as a joke. Of course it is sheer nonsense, for everybody who wants music knows very well all that he can do with the fingers on the piano.

He can produce all kinds of tones: not only louder or softer, shorter or longer tones, but also different qualities. It is possible on a piano to imitate, for instance, the sound of an oboe, a ‘cello’, a French horn. But it is not possible to imitate the sound of an oboe on a flute, or a clarinet on a violin; these other instruments always retain their own characteristics. That is why I said that the distinction of the piano is in its being the most neutral instrument.

The Bechstein piano fulfilled this demand for neutrality better than any other piano I have known. You could do almost anything on that piano. The Steinway—or rather the Steinway of twenty years ago, for it has changed somewhat since that time—was a piano which always wanted to show something. You see, it had much too much of a personality of its own.

At first, when I wanted to produce something like, let me say, the voice of a bird on a Steinway, the piano always sounded to me like the voice of a tenor instead of a bird. For many years, I had the feeling that the Steinway piano did not like me. An absurd idea, but I had that feeling. The Bechstein piano enabled me to show effects not possible on a Steinway. The tone of the Steinway vibrated much more: it has a different action. When you push a Steinway key very lightly and slowly down, it will stop before it has reached the bottom and requires a certain pressure, a second pressure to go down all the way. This is the »double action ». By now I am so used to it that it hardly irritates me any more. At first, however, it disturbed me greatly: for in order to produce a « fortissimo » you can play lightly, but whenever you want to play « pianissimo » you have to use a great deal of weight as otherwise the key would not go down. It certainly seems perverse.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

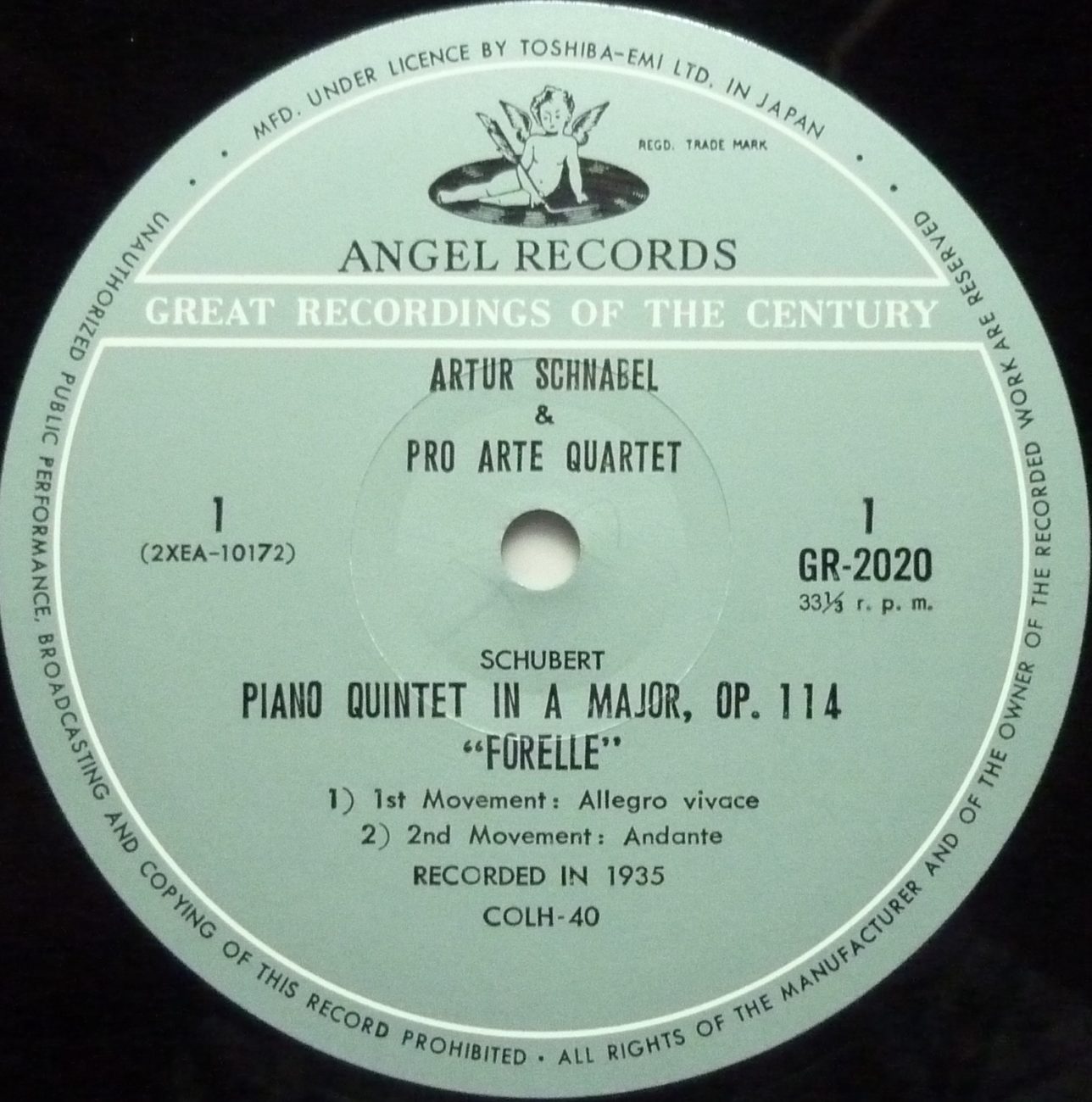

Artur Schnabel, piano; Alphonse Onnou, violon; Germain Prévost, alto,

Robert Maas, violoncelle, Claude Hobday, contrebasse

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – November 16, 1935

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Artur Schnabel et les membres précités du Quatuor Pro Arte (biographie par Anne van Malderen) ainsi que le contrebassiste Claude Hobday (1872-1954) ont enregistré ce quintette « La Truite » en 1935, mais la qualité sonore de cet étonnant microsillon japonais EMI-Toshiba GR-2020 du milieu des années soixante, gravé à partir de reports effectués à Londres par Anthony Griffith, donnerait plutôt à penser qu’il a été enregistré bien plus tard. L’explication est d’une part la prise de son du magicien Edward Fowler et d’autre part que l’on est en présence d’une copie directe et sans traitement de pressages vinyles effectués à partir de matrices métalliques de qualité exceptionnelle.

_______________

Artur Schnabel and said members of « Quatuor Pro Arte » (biography by Anne van Malderen) together with double-bass player Claude Hobday (1872-1954) have recorded this « Trout Quintet » in 1935, but the sound quality of this astonishing Japanese LP EMI-Toshiba GR-2020 from the mid-60s, cut from transfers made in London by Anthony Griffith would rather suggest a much later recording date. The explanation is on the one hand the sound captured by the magician Edward Fowler and on the other hand that this is an unprocessed transfer from vinyl pressings made from exceptionally clean metal parts.

Alphonse Onnou, violon

Robert Maas, violoncelle & Germain Prévost, alto

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

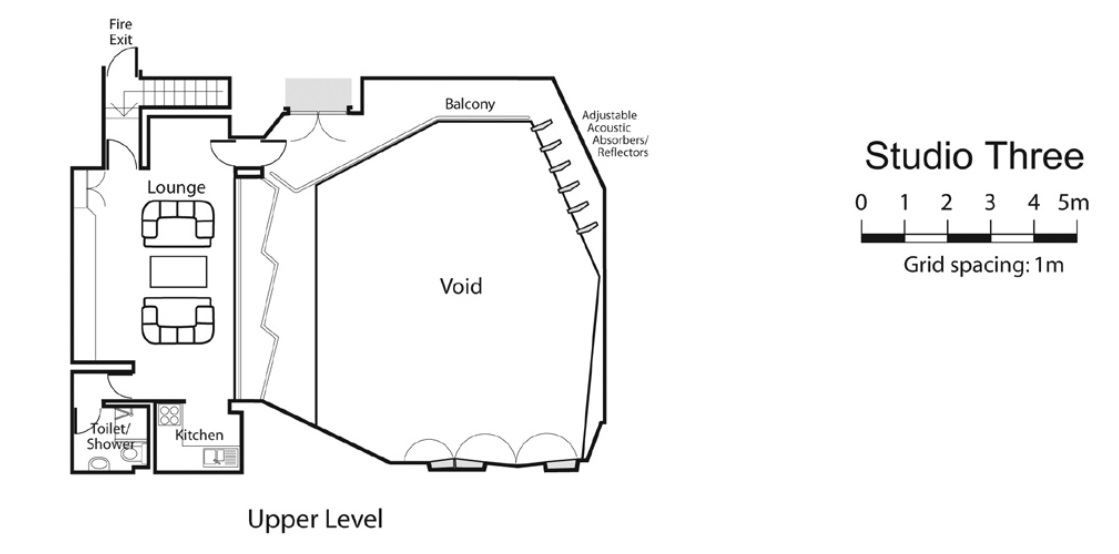

Bagatellen Op.33 – 10 novembre 1938

Bagatellen Op. 126 – 13 janvier 1937

Fantasia Op.77 – 14 janvier 1937

Rondo Op.51 n°1 – 13 avril 1933 – Rondo Op.129 – 13 janvier 1937 – Rondo WoO 49 – 14 janvier 1937

Menuet WoO 82 – Bagatelle WoO 59 – 10 novembre 1938

Artur Schnabel, piano

Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer Edward Fowler

33t. EMI-Toshiba GR 2120 & GR 2129

Ceci est le Volume I d’une série consacrée aux légendaires reports des enregistrements d’Artur Schnabel effectués par Anthony Griffith (1915-2005) et publiés en microsillon au Japon au milieu des années 60 par EMI-Toshiba. Leur particularité est qu’ils ont été non seulement réalisés à partir de pressages vinyle des matrices métalliques 78 tours d’origine, mais aussi qu’ils ont été reportés en 33 tours pratiquement sans aucun filtrage, et aucune autre édition ne reproduit aussi fidèlement le jeu du pianiste. Ils préservent également l’acoustique du studio d’enregistrement.

A la fin de l’année 1931, Fred Gaisberg (1873-1951), directeur artistique d’HMV a réussi à convaincre Artur Schnabel de faire des enregistrements. Le pianiste ne voulait pas fixer une fois pour toutes ses interprétations. Il avait aussi des exigences, notamment en ce qui concerne la reproduction de la dynamique. Pour caractériser les enregistrements, il utilisait le mot à double sens » Verplattung », signifiant aussi bien « mettre en disque » qu' »aplatir ». Son fils pianiste Karl-Ulrich était contre ces enregistrements, car il pensait que le matériel d’enregistrement n’était pas à même de reproduire (à titre de test) des effets tels que des sforzandos soudains, des basses bruyantes ou des excès de pédale, mais les premières prises réalisées l’ont lui aussi pleinement convaincu. Il faut dire aussi que les tous nouveaux Studios d’Abbey Road, inaugurés en novembre 1931, offraient de nombreuses nouvelles possibilités. HMV ayant accepté les conditions de Schnabel (enregistrer les 32 Sonates et les 5 Concertos de Beethoven, voire même toutes ses œuvres pour piano), un impressionnant programme d’enregistrement allant bien au delà du programme initial a pu être mené à bien entre janvier 1932 et janvier 1939 dans les Studios d’Abbey Road, au prix d’un considérable effort d’adaptation de la part du pianiste. Les Concertos étaient enregistrés au Studio n°1 et les œuvres pour piano seul et de musique de chambre au Studio n°3, avec toujours le même ingénieur du son, l’indispensable Edward Fowler (1902-1993) et toujours des pianos Bechstein.

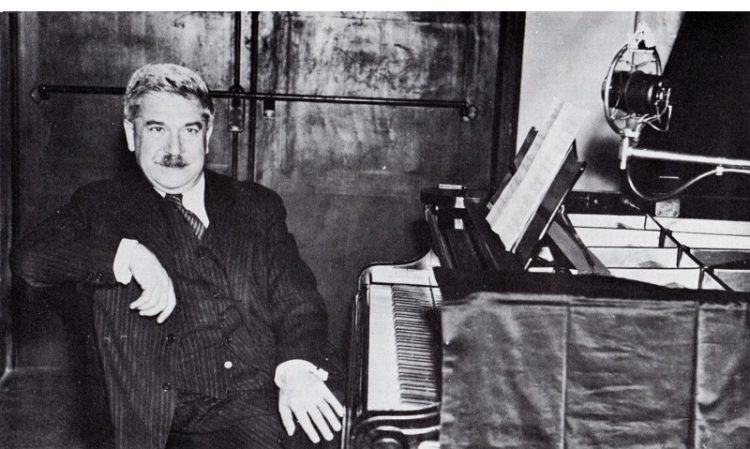

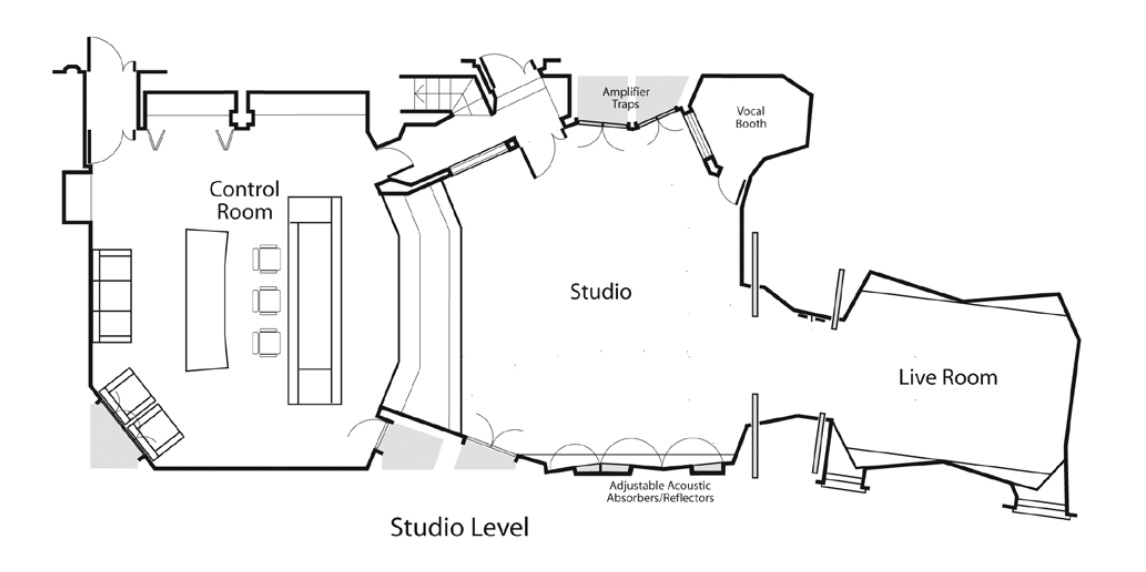

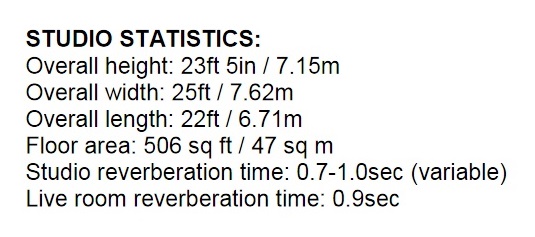

Le Studio n°3, où tant de grands pianistes ont enregistré, avait une surface étonnamment réduite (47 m2), une hauteur de 7,15 m et un temps de réverbération très court (réglable entre 0,7 et 1 seconde). Sa forme en polygone irrégulier a probablement été étudiée pour éviter des phénomènes de résonances et d’ondes stationnaires qui auraient coloré le son. Il comportait également un volume annexe (Live Room) pouvant être couplé ou non au Studio proprement dit.

La photo ci-dessus, prise en 1939, montre que, pour ces séances, le piano était placé contre une paroi du Studio. On notera également la position proche et plutôt inhabituelle du microphone.

A l’époque de ces rééditions japonaises, Edward Fowler dirigeait les Studios d’Abbey Road. Anthony Griffith, responsable de ces reports, avait quant à lui participé en tant qu’ingénieur du son à des enregistrements de Schnabel en 1946 (Beethoven Concertos n° 2 & 4) et 1950 (Schubert Impromptus Op.90).

Edward Fowler

This is Volume I of a series dedicated to the legendary transfers of Artur Schnabel’s recording made by Anthony Griffith (1915-2005), and published as LPs in Japan by EMI-Toshiba in the mid-60s. They have been not only transferred from vinyl pressings of the original 78rpm metal parts, but also this has been done without any significant filtering, and no other edition reproduces the pianist’s playing so faithfully. The acoustics of the recording studio is also preserved.

Toward the end of 1931, Fred Gaisberg (1873-1951), HMV’s artistic director succeeded in convincing Artur Schnabel to make recordings. The pianist did not want his performances fixed for eternity. He also had concerns, especially about the reproduction of dynamics. To describe recordings, he used the double-meaning word » Verplattung », which meant « disc-making » as well as « flattening out ». His pianist son Karl-Ulrich was against the idea of his father’s recordings because he believed that the recording machines could not respond well to a test with sudden sforzandos, loud bass or too much pedal, but the first trial takes fully convinced him. It must be said that the brand new Abbey Road Studios, inaugurated in November 1931, offered many new possibilities. HMV having agreed to Schnabel’s demand (recording the 32 Sonatas and the 5 Concertos by Beethoven and even all of his piano works), an impressive recording program extending much further than this initial program was succesfully conducted between January 1932 and January 1939 in the Abbey Road Studios, at the cost of ajustments taxing the pianist’s adaptability to the utmost. The Concertos were recorded in Studio n°1, and the solo piano as well as chamber music works in Studio n°3, always with the same recording engineer, the indispensable Edward Fowler (1902-1993) and always with Bechstein pianos.

Studio n°3, where so many great pianists recorded, had an astonishingly small floor area (47 m2 or 506 sq.ft.), an height of 7.15 m (23 ft 5 in) and a quite short reverberation time (adjustable between 0.7 sec et 1 sec). Its roughly polygonal shape was probably chosen to avoid resonances or stationary waves which might have coloured the sound. He was also comprised of an extra volume (Live Room) which it was possible to couple to the Studio proper.

The above picture, taken in 1939, shows that, for these sessions, the piano was close to a wall of the Studio. Note also the close and rather unusual position of the microphone.

When these Japanese LP re-issues were made, Edward Fowler was at the head of the Abbey Road Studios. Remastering engineer Anthony Griffith had himsef taken part as recording engineer to Schnabel post-war recordings in 1946 (Beethoven’s Concertos n° 2 & 4) and 1950 (Schubert’s Impromptus Op.90).

______________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.