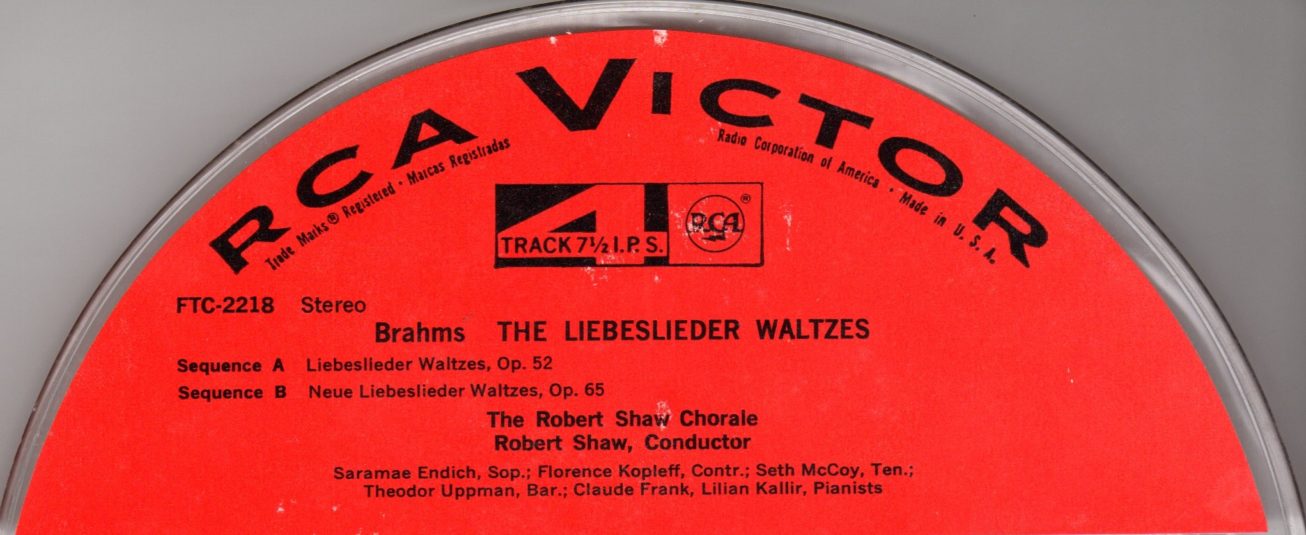

Étiquette : Bande/Tape

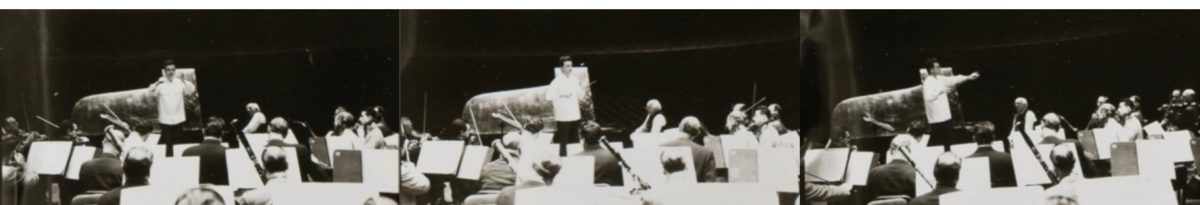

Rudolf Serkin Steinway piano – Guido Cantelli New York Philharmonic (NYPO)

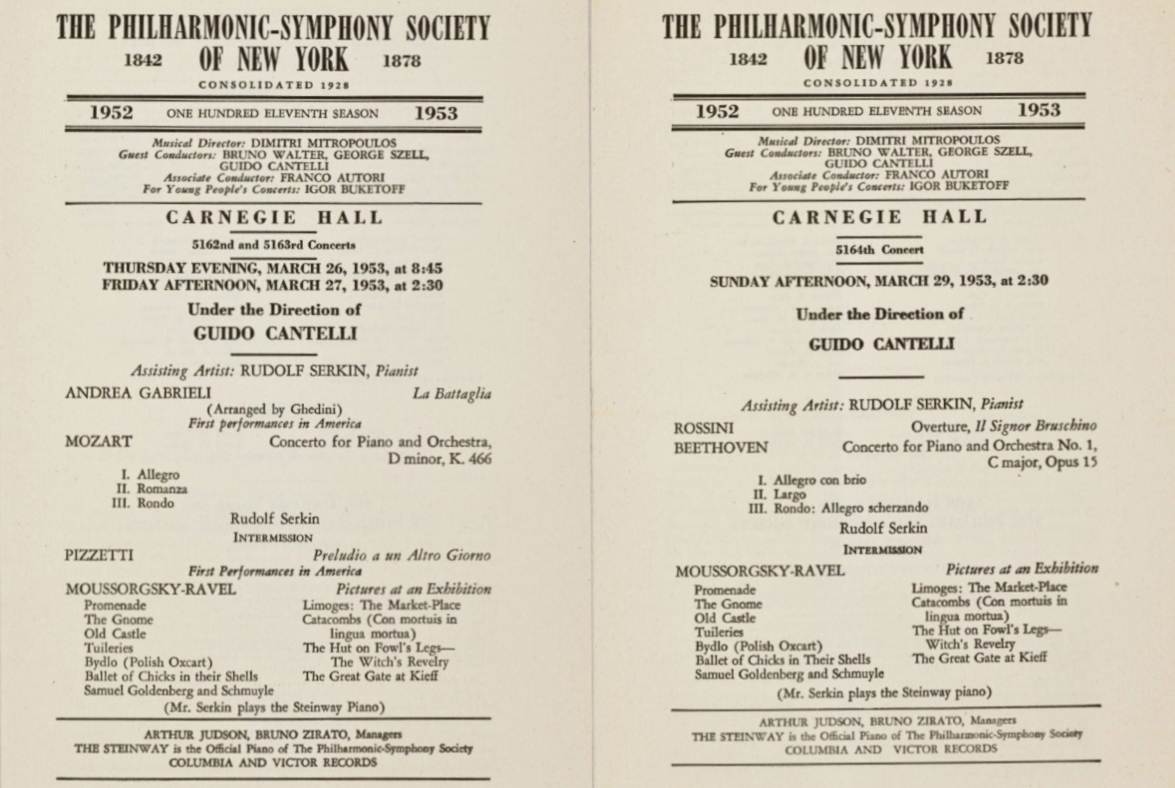

Mozart Concerto n°20 K. 466 (Cadenzas: Beethoven) – Carnegie Hall March 27, 1953

Beethoven Concerto n°1 Op.15 (Cadenza: Beethoven Version III) – Carnegie Hall March 29, 1953

Source: Bande / Tape – 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

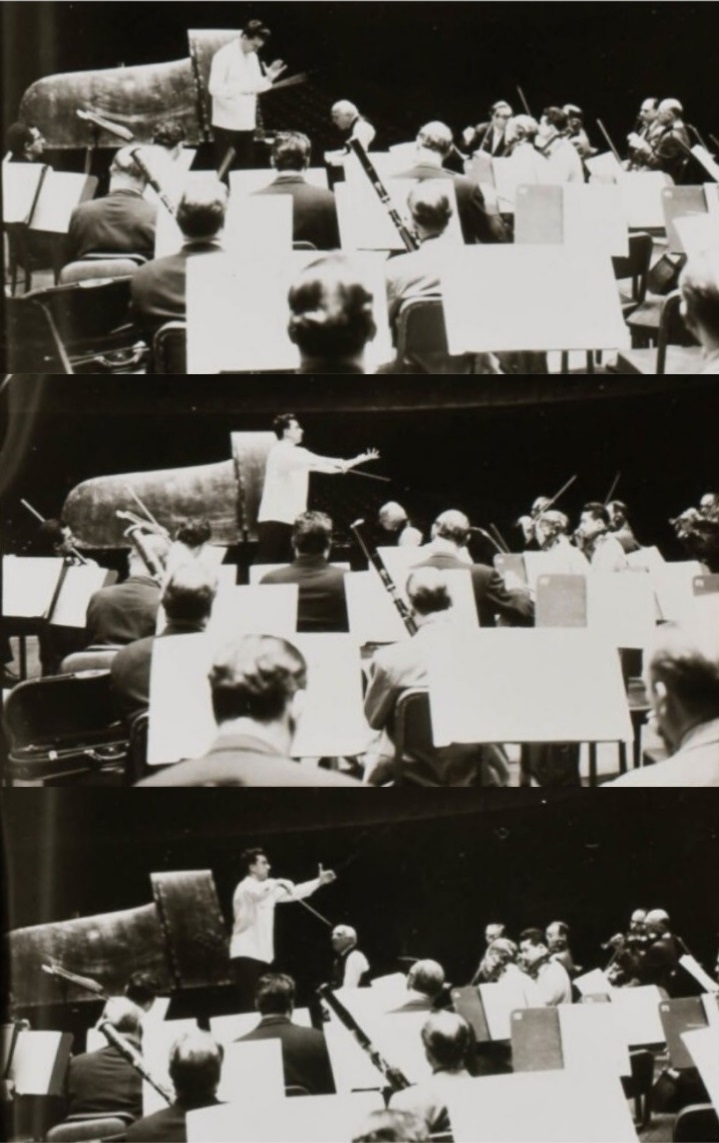

L’invitation de nombreux solistes faisait partie intégrante de la politique des programmes du New York Philharmonic (NYPO). Cantelli a commencé à diriger le NYPO en janvier 1952, et très vite, un nombre appréciable de grands pianistes se sont produits avec lui: successivement de 1952 à 1956, Rudolf Firkušný, Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer, Claudio Arrau, Rudolf Serkin, Robert Casadesus, Walter Gieseking et Wilhelm Backhaus, et une série d’enregistrements radiophoniques nous permet d’apprécier ses qualités exceptionnelles en tant que partenaire, bien plus qu’accompagnateur.

Rudolf Serkin a fêté son cinquantième anniversaire le 28 mars 1953. Avec Guido Cantelli et le NYPO, il a joué les 26 et 27 le Concerto n°20 K.466 de Mozart et le 29, le Concerto n°1 Op.15 de Beethoven. Le jour même de son anniversaire, il a répété le concerto de Beethoven avec l’orchestre.

D’habitude, la Radio ne retransmet que le concert du dimanche dont le programme, comme ici, diffère de ceux qui ont été joués au cours de la semaine. Nous avons cependant la chance d’avoir un enregistrement du concerto de Mozart joué le vendredi 27.

Les critiques musicaux new-yorkais se sont accordés pour trouver mémorable l’interprétation par Serkin du concerto de Mozart et pour louer la direction de Cantelli.

Harris Goldsmith, qui a assisté au concert du 29 alors qu’il était encore étudiant en piano, a relaté bien plus tard à quel point l’interprétation beethovénienne de Serkin, portée par les tempi rapides et fougueux de Cantelli, qui lui rappelaient ceux de Toscanini (avec Ania Dorfmann), était à la fois musicale et intense.

On notera dans le largo du concerto de Beethoven la finesse du dialogue entre le piano et le clarinettiste solo du NYPO, Robert Mc Ginnis.

Inviting a large number of soloists was an integral part of the schedule of the New York Philharmonic (NYPO). Cantelli started conducting the NYPO in January 1952, and very soon, a significant number of great pianists performed with him: successively from 1952 to 1956, Rudolf Firkušný, Nicole Henriot-Schweitzer, Claudio Arrau, Rudolf Serkin, Robert Casadesus, Walter Gieseking and Wilhelm Backhaus, and a series of broadcast recordings allows us to appreciate his exceptional qualities as a partner, rather than an accompanist.

Rudolf Serkin’s fiftieth birthday was on March 28, 1953. With Guido Cantelli and the NYPO, he played Mozart’s Concerto n°20 K.466 on the 26 and 27, and on the 29, Beethoven’s Concerto n°1 Op.15. On the birthday itself, he rehearsed the Beethoven concerto with the orchestra.

Usually, the Radio broadcasts only the Sunday concert whose program, as here, is different from those that have been played during the week. We are however lucky to have a recording of the Mozart’s concerto played on the Friday 27.

New York music critics agreed to find Serkin’s performance of the Mozart concerto memorable and to praise Cantelli’s conducting.

Harris Goldsmith, who attended the concert on the 29 when he was still a piano student, remembered many years later to what extend Serkin’s Beethoven performance, uplifted by Cantelli’s fast and fiery tempi, which reminded him of Toscanini’s (with Ania Dorfmann), was both musical and intense.

Note in the largo of the Beethoven’s concerto the delicacy of the dialog between the piano and the solo clarinettist of the NYPO, Robert Mc Ginnis.

Cadences/Cadenzas: Ferrucio Busoni

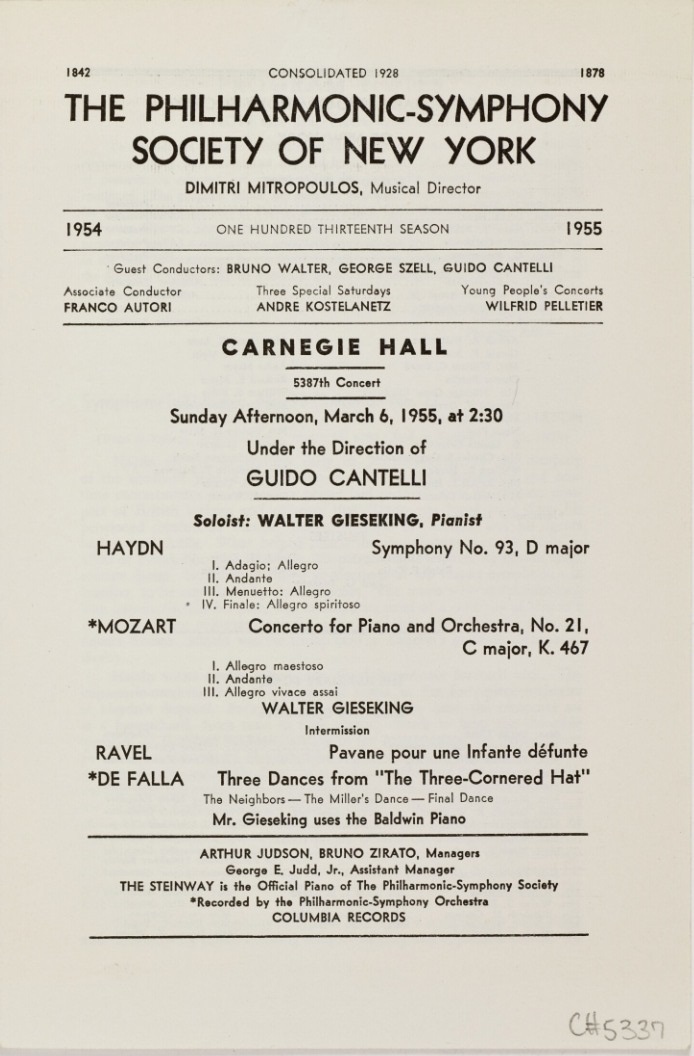

Walter Gieseking, Baldwin piano – Guido Cantelli New York Philharmonic (NYPO)

Carnegie Hall – March 6, 1955

Source: Bande / Tape – 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Cette interprétation du 6 octobre 1955 documente la rencontre entre Gieseking et Cantelli. C’est le retour de Gieseking avec le NYPO pour la première fois depuis 1939, et c’est une réussite. L’influence réciproque entre les deux interprètes conduit à une interprétation mémorable qui est on ne le peut mieux décrite que par le critique américain Bernard H. Haggin (1900-1987) dans son article de 1968 en hommage à Cantelli:

‘A l’époque, j’ai trouvé que beaucoup d’interprétations de Cantelli étaient merveilleuses; et merveilleux est le mot pour certaines que j’ai entendues récemment, en particulier celle du Concerto pour piano de Mozart K.467. Dans mon expérience, seul Toscanini apportait aux solistes des contextes orchestraux aussi beaux et aussi efficaces que ceux de Cantelli; et dans mon expérience, Toscanini a fourni le précédent pour la chose extraordinaire qui se passe dans l’interprétation par Cantelli du concerto K.467. A un concert du New York Philharmonic en 1934, j’ai entendu Toscanini diriger les concertos K.467 et K.466 avec José Iturbi en soliste, et j’ai entendu Iturbi—sous l’impulsion de la personnalité et du magnétisme du chef—rivaliser avec le jeu puissant de l’orchestre avec un jeu personnel qui était remarquablement différent de son jeu embelli habituel, un style de salon, pour jouer Mozart.

Et la même chose se produit dans l’exécution par Cantelli du concerto K.467. Ce que l’on s’attend à entendre après l’introduction orchestrale superbement exécutée est le style miniature finement ciselé pour jouer Mozart que l’on entend toujours de la part de Gieseking; mais ce que l’on entend à la place, ce sont une énonciation forte et des phrasés forts pour jouer la mélodie, et des doigtés forts pour les séquences de notes rapides et les figurations qui doivent avoir surpris Gieseking comme ils doivent avoir surpris ses auditeurs en 1955 au concert du New York Philharmonic. Jamais auparavant, il n’avait joué Mozart comme cela; et il l’a fait sous la même impulsion de la part de Cantelli que celle que Toscanini avait exercé sur Iturbi. Sous cette impulsion, Iturbi a réussi, et Gieseking réussit, dans l’extraordinaire Andante ce que je n’ai entendu d’aucun autre pianiste au concert: une énonciation et une articulation de la longue cantilène du piano qui soit comparable avec l’enregistrement discographique de Schnabel. Et le jeu de Gieseking dans cette cantilène, contrairement à celui de Schnabel, s’exprime dans le contexte du jeu superbe de la partie orchestrale qui est constamment active—par exemple, les commentaires poignants des bois qui intensifient certaines des énonciations du piano.’

![]()

This October 6, 1955 concert illustrates the meeting between Gieseking and Cantelli. It is Gieseking’s return with the NYPO for the first time since 1939 and it is a success. The reciprocal influence between both musicians leads to a memorable performance best described by US critic Bernard H. Haggin (1900-1987) in his 1968 tribute to Cantelli:

‘Many of Cantelli’s performances I found marvelous at the time; and marvelous is the word for those I have heard recently—in particular the one of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K.467. Only Toscanini, in my experience, provided soloists with orchestral contexts as beautifully made and as effective as Cantelli’s; and Toscanini provided the one precedent in my experience for the astounding thing that happens in Cantelli’s performance of K.467. At a New York Philharmonic concert in 1934, I heard Toscanini perform K.467 and 466 with José Iturbi as soloist, and heard Iturbi—under the compulsion of the personality and magnetism of the man on the podium—match the orchestra’s powerful playing with playing of his own that was strikingly different from his customary prettified salon-style playing of Mozart.

And the same thing happens in Cantelli’s performance of K.467. What one expects to hear after the superbly performed orchestral introduction is the finely chiseled miniature-scale playing of Mozart that one always heard Gieseking do; but what one hears instead is a strongly enunciated, strongly phrased playing of melody, a strong-fingered execution of runs and figuration, that may have amazed Gieseking as it must have amazed his listeners at the New York Philharmonic concert in 1955. He had never played Mozart that way before; and he did so then under the same compulsion from Cantelli as Toscanini had exercised on Iturbi. Under that compulsion, Iturbi achieved, and Gieseking achieves, in the extraordinary Andante what I have heard live from no other pianist: an enunciation and articulation of the piano’s long cantilena comparable with Schnabel’s in his recorded performance. And Gieseking’s playing of this cantilena, unlike Schnabel’s, is heard in the context of the superb playing of the constantly active orchestral part—e.g., the poignant woodwind comments intensifying certain of the piano’s statements.’

Karl Münchinger Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO)

Wien Sofiensaal: 10-12 avril 1961

Prod: Christopher Raeburn – Eng: James Brown

Source Bande/Tape LCL 80093 (4 pistes 19 cm/s / 4 tracks 7.5 ips)

Voici deux autres symphonies de Haydn parmi les plus connues, que nous offrent les Wiener Philharmoniker à leur sommet sous la baguette de Münchinger, toujours pertinent dans ce répertoire.

Here are two further most celebrated Haydn symphonies, performed by the Wiener Philharmoniker in top form, under the direction of Karl Münchinger, always relevant in this repertoire.

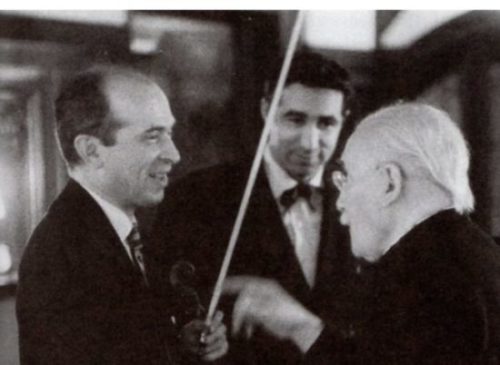

Arturo Toscanini – NBC Symphony Orchestra

Beethoven Symphony n°6 Op.68

Carnegie Hall – March 7, 1954 Source: Bande / Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Les deux dernières saisons (1952-1953 et 1953-1954) de Toscanini à la tête du NBC SO ont apporté deux modifications significatives.

Tout d’abord, le remplacement de Mischa Mischakoff par Daniel Guilet, membre de l’orchestre depuis 1944, en tant que Concertmaster a ouvert de nouvelles perspectives. Guilet était un musicien d’envergure, spécialiste de musique de chambre (Quatuor Calvet, Guilet Quartet) et il sera d’ailleurs peu après (en 1955) un des fondateurs du Beaux Arts Trio.

La deuxième modification était l’amélioration des techniques d’enregistrement chez RCA, avec le recours à moins de microphones (début 1953, la 9ème de Dvorak, la 9ème de Schubert et les Tableaux d’une Exposition de Moussorgski ont été enregistrés à Carnegie Hall avec un seul microphone). Les deux derniers concerts, le 21 mars et le 4 avril 1954, ont même été captés en stéréo expérimentale.

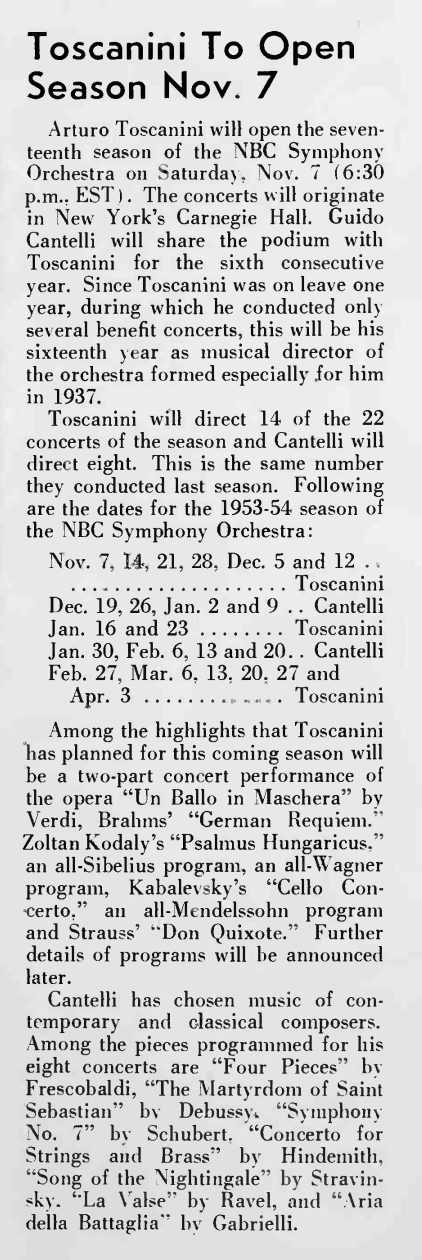

Début octobre 1953, le programme de la saison à venir a été annoncé et Toscanini a fait savoir depuis l’Italie que ce sera pour lui la dernière:

___________________

NBC Chimes – October 1953

Très vite, RCA a adapté sa stratégie et le programme publié a été complètement revu pour utiliser uniquement les prises de son réalisées lors des répétitions et des concerts pour produire des enregistrements commerciaux qui manquaient à sa discographie, et ce d’autant plus que Toscanini, on le sait, n’a pas pu diriger les deux premiers programmes (8 et 15 novembre) pour lesquels il a été remplacé par Pierre Monteux, et que pour celui du 28 mars, il a invité Charles Munch à le remplacer. Les concerts annoncés initialement pour le samedi à 18h30 ont été reprogrammés le dimanche à la même heure, juste après la retransmission (14h30) du concert dominical du New York Philharmonic.

Programme initial du concert du 8 Novembre / Initial Program of the November 8 concert

Il a donc dirigé 11 concerts dont 8 ont servi en tout ou partie pour des enregistrements commerciaux (dans la liste ci-dessous, les œuvres ayant fait l’objet à cette occasion d’un enregistrement commercial sont soulignées). Si on met à part les deux derniers concerts qui sont notoirement très inférieurs au reste de la saison, il reste un joyau inédit, c’est la ‘Pastorale’ du 7 mars 1954, une grand réussite, fort bien captée, dans laquelle Toscanini se montre étonnamment détendu, voir euphorique, ou plus précisément ‘heiter’ comme Beethoven le préconise pour le premier mouvement.

Ce jour là, Cantelli dirigeait le NYPO et les deux chefs se sont retrouvés en concurrence radiophonique!

___________________

22 Nov. 1953: Brahms: Tragic Overture Op.81; Strauss: Don Quixote (Frank Miller, cello – Carlton Cooley, viola)

29 Nov. 1953: Wagner: Tannhäuser Prelude Act III; Berlioz: Harold en Italie Op.16 (Carlton Cooley, viola)

6 Dec. 1953: Beethoven ; Coriolan Ouv.; Symphony n°3 Op.55

13 Dec. 1953: Moussorgsky: Khovantschina Prelude; Franck: les Eolides; Weber: Invitation à la Valse Op.65; Mendelssohn: Symphony n°5 Op.107 ‘Reformation’

17 & 24 Jan. 1954: Verdi: Un Ballo in Maschera (Pierce, Merrill, Nelli, Turner, Haskins, Moscona, Scott)

28 Feb. 1954: Mendelssohn: Symphony n°4 Op.90; Strauss: Don Juan Op.20; Weber: Oberon Ouv.

7 Mar. 1954: Beethoven: Leonore II Op.72b; Symphony n°6 Op.68

14 Mar. 1954: Vivaldi: Concerto grosso Op.3 n°11; Verdi: Te Deum; Boïto: Mefistofele Prologue Robert Shaw Chorale – Nicola Moscona The Columbus Boychoir (Boïto)

21 Mar. 1954: Rossini: Il Barbiere di Siviglia Ouv.; Tchaïkovsky: Symphony n¨6 Op. 74

4 Apr. 1954: Wagner Lohengrin: Prelude; Siegfried: Waldbeben; Götterdämmerung: Dämmerrung und Siegfrieds Rheinfahrt; Tannhäuser: Ouverture & Bacchanale; Meistersinger: Prelude

____________________

Toscanini’s last two seasons (1952-1953 and 1953-1954) as Music Director of the NBC SO have brought two main changes.

Firstly, the replacement of Mischa Mischakoff by Daniel Guilet, member of the orchestra since 1944, as Concertmaster has opened up new perspectives. Guilet was a great musician, and his speciality was chamber music (Quatuor Calvet, Guilet Quartet) and he was soon to be (in 1955) one of the founding members of the Beaux Arts Trio.

The second change was an improvement in RCA recording techniques, with less microphones (at the beginning of 1953, Dvorak’s 9th, Schubert’s 9th and Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition were recorded in Carnegie Hall with a single microphone). The last two concerts of 21 March and of 4 April 1954 were even recorded in experimental Stereo.

At the beginning of October 1953, the program for the season to come was announced and Toscanini, from Italy, let it be known that for him, it would be the last.

Very quickly, RCA adapted its strategy and the published program was thoroughly reconsidered to use only recorded material from the rehearsals and from the concerts to produce commercial recordings that were missing in his discography and all the more so, since Toscanini, as we know, was not able to conduct the first two programs (8 and 15 November) for which he was replaced by Monteux. and for the one of 28 March, he invited Charles Munch as a substitute. The concerts, initially scheduled on Saturdays at 6.30pm were moved on Sundays at the same hour, shortly after the Sunday broadcast (2.30pm) of the New York Philharmonic.

He thus conducted 11 concerts, 8 of which were used at least partly to make commercial recordings (in the above list, the works that led to commercial recordings that season are underlined). If we set aside the last two concerts that were notoriously very inferior to the others from this season, there remains an unpublished jewel, namely the ‘Pastorale’ of 7 March 1954, a great performance, and very well recorded, in which Toscanini is astonishly relaxed, even euphoric, or better said ‘heiter’ as Beethoven requests for the first movement.

That very day, Cantelli conducted the NYPO and both conductors had competing broadcasts!

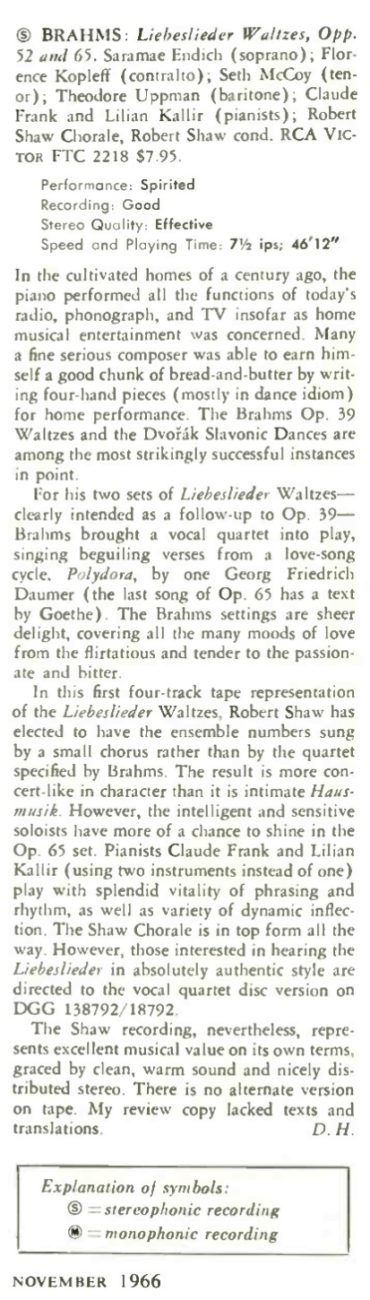

The Robert Shaw Chorale

Saramae Endich, soprano; Florence Kopleff, contralto;

Seth McCoy, tenor; Theodor Uppman, baritone

Claude Frank & Lilian Kallir, pianos

Enr/Rec: New-York 1965 – Source: Bande/Tape: 4 pistes 19 cm/s / 4-track 7.5 ips FTC-2218

Robert Shaw (1916-1999) est avant tout connu pour sa collaboration avec Arturo Toscanini entre 1948, année où il fonde la Robert Shaw Chorale, et 1954. Lors de la dernière saison de Toscanini avec le NBC SO, il était prévu que Toscanini dirige avec la participation de la Robert Shaw Chorale ‘Un Ballo in Maschera’ de Verdi, ainsi que le Psalmus Hungaricus de Kodaly. Pour le dernier concert, le 4 avril 1954, le choix s’était porté sur le Deutsches Requiem de Brahms (chanté cette fois en allemand), mais ce projet a été abandonné et Walter Legge, dans une lettre du 5 janvier 1954 à Walter Toscanini, a exprimé sa profonde déception que le programme de ce concert ait été annulé et remplacé par un concert Wagner, et ce d’autant plus qu’il était prévu que son épouse Elizabeth Schwarzkopf chantât la partie de soprano du Requiem de Brahms. Quant à Robert Shaw, sa dernière collaboration avec Toscanini a été pour le magnifique concert du 14 mars 1954 (Boïto Mefistofele Prologue et Verdi Te Deum).

Radio Age – October 1953

_________________

Pour cet enregistrement, réalisé peu de temps avant qu’il devienne le Directeur Musical de l’Orchestre Symphonique d’Atlanta, Robert Shaw a choisi d’utiliser un chœur de chambre, en ayant toutefois recours à un quatuor de solistes vocaux pour certains des Lieder, essentiellement dans l’Op.65. Les critiques de l’ époque ont considéré que cela nuisait à l’intimité de l’œuvre qui relève de la ‘Hausmusik’. Toutefois, les enregistrements sont souvent réalisés sans les reprises et avec des chanteurs connus, ce qui donne un caractère de quatuor vocal dont les membres sont nettement individualisés. En tous cas, l’interprétation de Shaw est pleine de finesse et même, on se croirait à Vienne !

Hi-Fi Stereo Review – November 1966

Robert Shaw (1916-1999) is above all known for his performances with Arturo Toscanini between 1948, the year he grounded the Robert Shaw Chorale, and 1954. for Toscanini’s last season with the NBC SO, it was scheduled that Toscanini would conduct with the Robert Shaw Chorale Verdi’s ‘Un Ballo in Maschera’, as well as the Psalmus Hungaricus by Kodaly. For the last concert, on Avril 4, 1954, the choice was Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem (this time sung in German), but the project was abandoned and Walter Legge, in a letter he sent to Walter Toscanini on January 5, 1954, expressed his deep disappointment that the programme of this concert had been cancelled and replaced by a Wagner program, all the more so since his wife Elizabeth Schwarzkopf was to sing the soprano part in the Brahms’ Requiem. As to Robert Shaw, his last performance with Toscanini was for the wonderful concert of March, 14 1954 (Boïto Mefistofele Prologue and Verdi Te Deum).

_________________

For this recording, made shortly before he became the Music Director of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, Robert Shaw chose a chamber choir, while also having resort to a quartet of vocal soloists for some of the Lieder, mainly in Op.65. At the time, the critics objected that it was detrimental to the ‘Hausmusik’ intimacy of the work. However, recordings are often made without the repeats and with known singers, which form a vocal quartet vocal whose members are clearly individualized. Be it what it may, Shaw’s performance is full of delicacy, and quite Viennese, too!