Étiquette : Beethoven

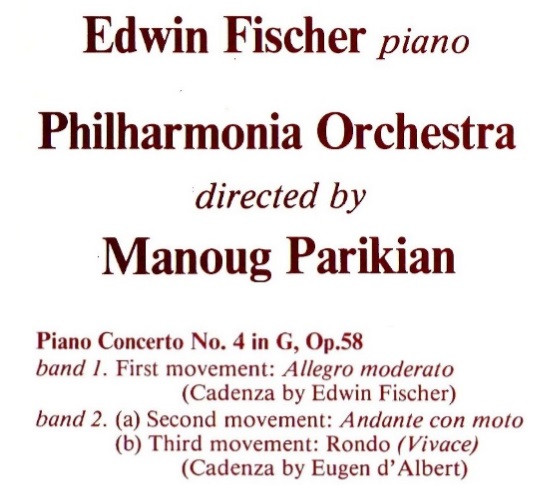

Edwin Fischer – Philharmonia Orchestra

Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58

London Abbey Road Studio n°1 – 4,9 & 14 Mai 1954

Prod: Walter Legge & Walter Jellinek – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source 33t/LP: RLS 2900013 ‘HMV Treasury’

Entre le 3 et le 20 mai 1954, Edwin Fischer a entrepris une importante série d’enregistrements à Londres, dont trois Concertos avec le Philharmonia Orchestra.

Cette année là, du fait de difficultés qui ont surgi avec les musiciens suisses, le Comité d’organisation des Luzerner Festwochen a du renoncer aux services de l’Orchestre Suisse du Festival, et il a été annoncé en janvier 1954 que ce serait le Philharmonia Orchestra qui assurerait tous les concerts des Semaines Musicales de Lucerne (article de René Klopfenstein dans ‘La Liberté’ du 9 janvier 1954).

Suite à ce prestigieux engagement, l’Ambassadeur de Suisse à Londres, Henry de Torrenté, organisa le 5 mai au Goldsmith’s Hall un concert de gala consacré à des œuvres de Bach et de Mozart auquel étaient conviés en présence de nombreux officiels Edwin Fischer et le Philharmonia Orchestra ainsi que la violoniste suisse Marie-Madeleine Tschachtli.

Et plus tard, le 18 août, Fischer a dirigé le Philharmonia Orchestra pour le 5ème concert symphonique du Festival avec au programme le Concerto Brandebourgeois n°2 de Bach, le Concerto n°22 K.482 de Mozart et le Triple Concerto Op.56 de Beethoven (avec Schneiderhan et Mainardi). La ‘masterclass’ de Fischer a débuté le lendemain du concert, après une réception informelle organisée par Walter Strebi, au cours de laquelle Fischer a joué la sonate ‘Waldstein’.

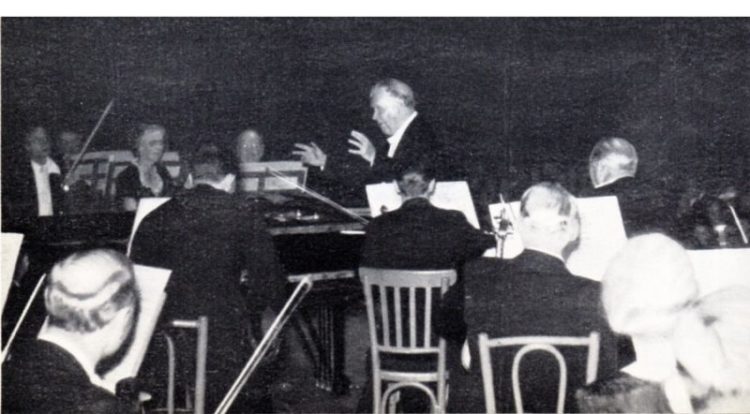

Dans ‘L’Impartial’ du 20 août, est paru un long article du critique Jean-Marie Nussbaum qui relate son expérience d’une des répétitions de Fischer: ‘Je sors d’une répétition du concert Edwin Fischer – Orchestre Philharmonia de Londres. Rien de plus agréable que d’assister à une telle séance de travail. Les exécutants, sanglés le soir dans leur habit et leur respectabilité jouent ici en manches de chemise, affalés sur leur chaise en des positions fort peu académiques. Ce vaste gentleman ventripotent et moustachu taquine du mouchoir sa contrebasse empoussiérée. Bref, on est à l’aise…

Dans la salle, quatre ou cinq langues, ou plus. Il y a un nombre inusité de «techniciens » de la musique. Voici le violoncelliste français Pierre Fournier, suprêmement distingué et qui sait jouer avec art, et son accompagnatrice Reine Gianoli, au cheveu plat comme l’imagination d’un caricaturiste romand. Et d’autres, que naturellement nous ne connaissons pas.

Fischer, ce grand pianiste suisse, est déjà au milieu de ses « poulains ». Tête de lion beethovénien posée pile sur un corps râblé et court sur pattes de petit bourgeois argovien, il serre des mains à droite, à gauche, et hop! Il tape dans ses mains au-dessus de sa tête pour attirer l’attention, étend les bras et… c’est !a prodigieuse entrée du Deuxième Brandebourgeois qui se fait entendre, puis une série de pages (car on ne joue pas tout) de ce luxuriant et baroque concerto, où font merveille le violon, la flûte, le hautbois, la trompette et le clavecin du « Philharmonia ». Quelle distance entre ce jeu et celui de Cortot (qui a dirigé les Brandebourgeois à Paris)! Comme le second est dix-huitième, fulgurant, libre, et Fischer romantique! Et que tous les deux sont beaux, cependant…

Arrêt: on s’explique mi en anglais, mi en allemand. Fischer court de-ci de-là griffonner quelques indications dans les partitions. Éclat de rire: le bon chef suisse a dû faire un «witz»… Et on repart…On va jouer l’un des plus beaux Concertos pour piano et orchestre de Mozart, celui en mi, grâce auquel, avec celui en ré, nous avons été converti à la religion mozartienne à laquelle jamais nous ne serons infidèle. Fischer joue la partie de piano et dirige en même temps. Le petit homme bondit de son instrument comme un diable de sa boite pour indiquer une entrée, une inflexion, une tendresse. Puis retombe sur le clavier, et la merveilleuse rêverie recommence…

— Ah! mais cette pédale.. . Il y met trop de pédale, s’exclame derrière moi un auditeur barbu, qui suit la musique sur la partition.

— Vous voulez peut-être aller jouer à sa place ? riposte vertement un spectateur à lunettes qui a l’air d’être de la partie.

Cher Fischer! Peut-être en effet ne menez-vous pas votre orchestre avec la rigueur de M. Furtwängler; vous jouez avec lui comme avec votre piano; je n’en sais rien. Mais ce que je sais , c’est que vous avez créé, je dis bien créé, une interprétation de Mozart que l’on n’oubliera plus.

Vous avez pensé que la musique était faite d’émotion, et non de technique, et vous avez mis vos dons magnifiques d’exécutant au service de votre cœur: vous avez bien fait! La qualité de votre main, quand vous jouiez ce Concerto, égalait celle des plus grands artistes: ceux qui miraculeusement réunissent la forme et le fond dans la simplicité et le naturel du style. Votre Mozart est romantique? Certes: qui a jamais dit qu’il ne pouvait pas l’être?

Et bien sûr, si lors des séances d’enregistrement de mai 1954, Fischer, qui comme l’a rapporté Gerald Kingsley, a bien dirigé l’orchestre, et si le rôle de Manoug Parikian qui a mené (‘directed’) l’orchestre sans toutefois le diriger (‘conduct’), n’est pas défini, cela pose une question. Par contre, le récit de la répétition de Lucerne ne montre pas que Manoug Parikian aurait pris une part quelconque dans l’interprétation des deux œuvres de Bach et de Mozart.

Le critique du ‘Neue Zürcher Zeitung’ a d’ailleurs relevé dans le numéro du 21 août: ‘Cela n’a pas été sans imprécisions, surtout dans le Concerto pour piano en mi bémol majeur K. 482 de Mozart, car lorsqu’il devait jouer, Fischer n’a pu donner ses instructions de direction que par des regards et des mouvements de tête sur de très longues plages de musique’.

On ne sait pas, bien sûr, quelle est la réponse, mais ce que l’on sait, c’est qu’il est plausible d’émettre l’hypothèse que, pour les enregistrements de mai 1954, le besoin se soit fait sentir de recourir aux services de Parikian juste pour éviter de telles imprécisions.

Between 3 and 20 May 1954, Edwin Fischer undertook a major series of recordings in London, including three Concertos with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

That year, due to difficulties that arose with the Swiss musicians, the Luzerner Festwochen Organising Committee had to forego the services of the Swiss Festival Orchestra, and it was announced in January 1954 that it would be the Philharmonia Orchestra that would give all the concerts at the Lucerne Music Festival (article by René Klopfenstein in ‘La Liberté’ of 9 January 1954).

Following this prestigious engagement, the Swiss Ambassador in London, Henry de Torrenté, organised a gala concert of works by Bach and Mozart at Goldsmith’s Hall on 5 May, to which Edwin Fischer and the Philharmonia Orchestra as well as the Swiss violinist Marie-Madeleine Tschachtli were invited in the presence of numerous officials.

And later, on 18 August, Fischer conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra in the Festival’s 5th symphony concert, featuring Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto n°2, Mozart’s Concerto n°22 K.482 and Beethoven’s Triple Concerto Op.56 (with Schneiderhan and Mainardi). Fischer’s masterclass began the day after the concert, with an informal reception hosted by Walter Strebi and Fischer playing the Waldstein Sonata.

In ‘L’Impartial’ of 20 August, music critic Jean-Marie Nussbaum published a long article recounting his experience of one of Fischer’s rehearsals: ‘I’ve just come from a rehearsal of the Edwin Fischer – London Philharmonia Orchestra concert. There’s nothing more pleasant than attending such a work session. The performers, strapped into their formal wear and respectability in the evening, play here in their shirt sleeves, slumped in their chairs in highly unacademic positions. This vast, busty gentleman with a moustache teases his dusty double bass with his handkerchief. In short, you feel at ease…

In the hall, four or five languages, or more. There are an unusual number of musical ‘technicians’. There’s the French cellist Pierre Fournier, supremely distinguished and a masterful player, and his accompanist Reine Gianoli, with hair as flat as the imagination of a Swiss cartoonist. And there are others, of course, whom we don’t know.

Fischer, this great Swiss pianist, is already among his ‘boys’. With his Beethovenian lion’s head poised on the short, stocky body of an Aargau bourgeois, he shakes hands left and right, claps his hands above his head to attract attention, stretches out his arms and… here it is! the prodigious entrance to the Second Brandenburg can be heard, followed by a series of pages (because they don’t play it in its entirety) from this lush, baroque concerto, featuring the violin, flute, oboe, trumpet and harpsichord of the Philharmonia. What a distance between this playing and that of Cortot (who conducted the Brandebourgeois in Paris)! How eighteenth-century, dazzling, free, and Fischer romantic! And how beautiful they both are, though…

We come to a pause: explanations are exchanged half in English, half in German. Fischer runs here and there to scribble a few indications in the scores. A burst of laughter: the good Swiss chef must have made a « witz »… And off we go again. To play one of Mozart’s most beautiful Concertos for piano and orchestra, the one in E, thanks to which, along with the one in D, we had been converted to the Mozartean religion, to which we would never be unfaithful. Fischer plays the piano part and conducts at the same time. The little man leaps from his instrument like a devil from a box to indicate an entrance, an inflection, a tenderness. Then he falls back on the keyboard, and the marvellous reverie begins again…

– Ah! but that pedal… . There is too much pedal, » exclaims a bearded listener behind me, following the music on the score.

– Perhaps you’d like to go and play in his place? » retorts a spectator with glasses who seems to be well informed.

Dear Fischer! Perhaps you don’t conduct your orchestra with Mr Furtwängler’s rigour; you play with him as with your piano; I don’t know. But what I do know is that you have created, and I mean created, an interpretation of Mozart that will never be forgotten.

You thought that music was about emotion, not technique, and you put your magnificent gifts as a performer at the service of your heart: you did well! The quality of your hand when you played this Concerto was equal to that of the greatest artists: those who miraculously combine form and content in a simple, natural style. Is your Mozart romantic? Of course: who ever said he couldn’t be?’

And of course, if for the May 1954 recording sessions, Fischer, as Gerald Kingsley reports, did conduct the orchestra, and if the role of Manoug Parikian, who ‘directed’ the orchestra without conducting it, is not defined, this raises a question. On the other hand, the account of the rehearsal in Lucerne does not show that Manoug Parikian took any part whatsoever in the interpretation of the two works by Bach and Mozart.

The critic of the ‘Neue Zürcher Zeitung’ noted this in the issue of 21 August: ‘Mozart’s Piano Concerto in E flat major K. 482 in particular was not without inaccuracies, because for considerable stretches when Fischer had to play, he could only give his conducting instructions with glances and head movements’.

We don’t know the answer of course, but what we do know, is that it is plausible to assume that, for the May 1954 recordings, it was deemed necessary to call on Parikian’s services with a view to avoiding such inaccuracies.

Avec nos remerciements à Roger Smithson ainsi qu’à Gerald Kingsley, qui était également présent à la répétition de Lucerne / With thanks to Roger Smithson as well as to Gerald Kingsley, who also attended the Lucerne rehearsal.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

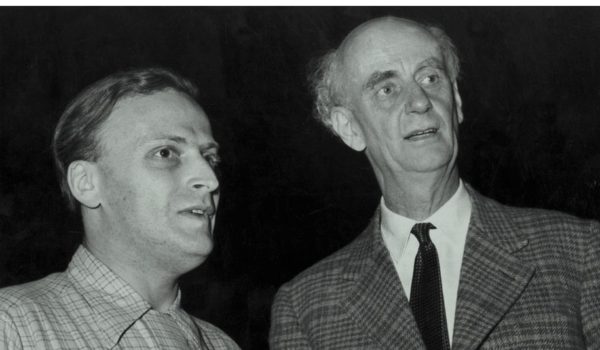

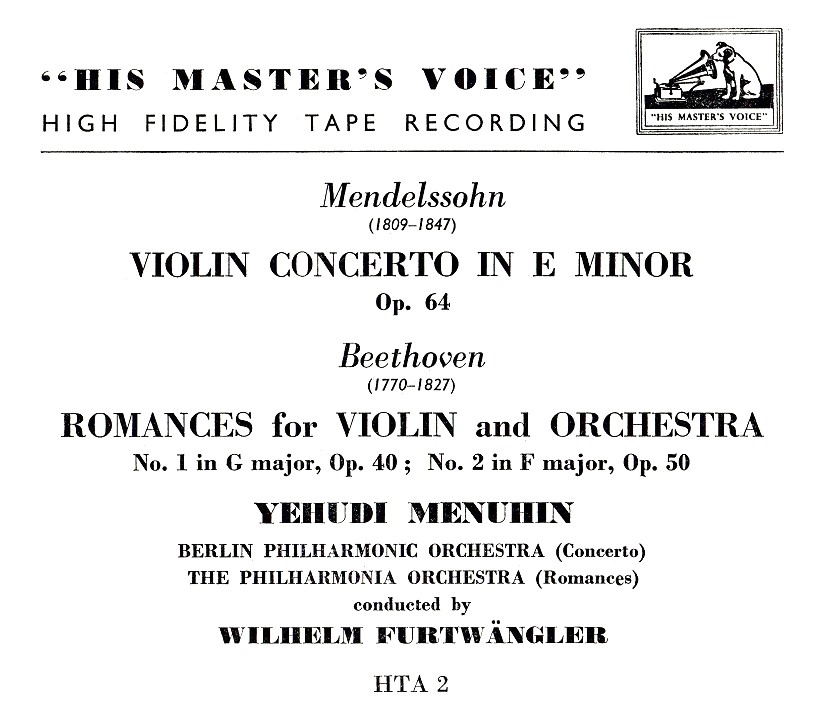

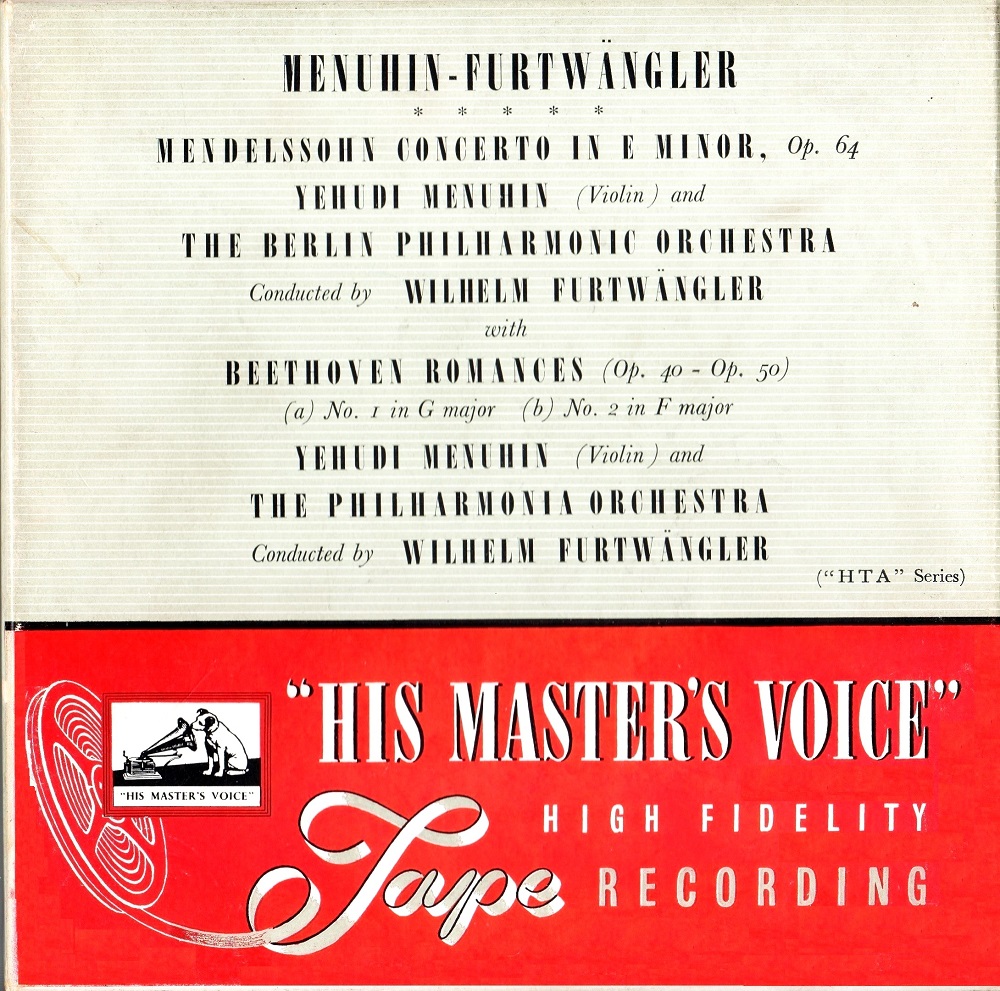

Yehudi Menuhin & Wilhelm Furtwängler

Mendelssohn: Concerto Op.64 Berliner Philharmoniker (BPO)

Berlin Jesus-Christus Kirche – 25 & 26 Mai 1952

Eng: Robert Beckett

______

Beethoven: Romances Op.40 & 50 Philharmonia Orchestra

London Kingsway Hall – 9 April 1953

Prod: Lawrence Collingwood & David Bicknell – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTA 2

Menuhin et Furtwängler ont joué pour la première fois ensemble le Concerto Op.64 de Mendelssohn le 29 septembre 1949 au Royal Albert Hall de Londres avec les Wiener Philharmoniker.

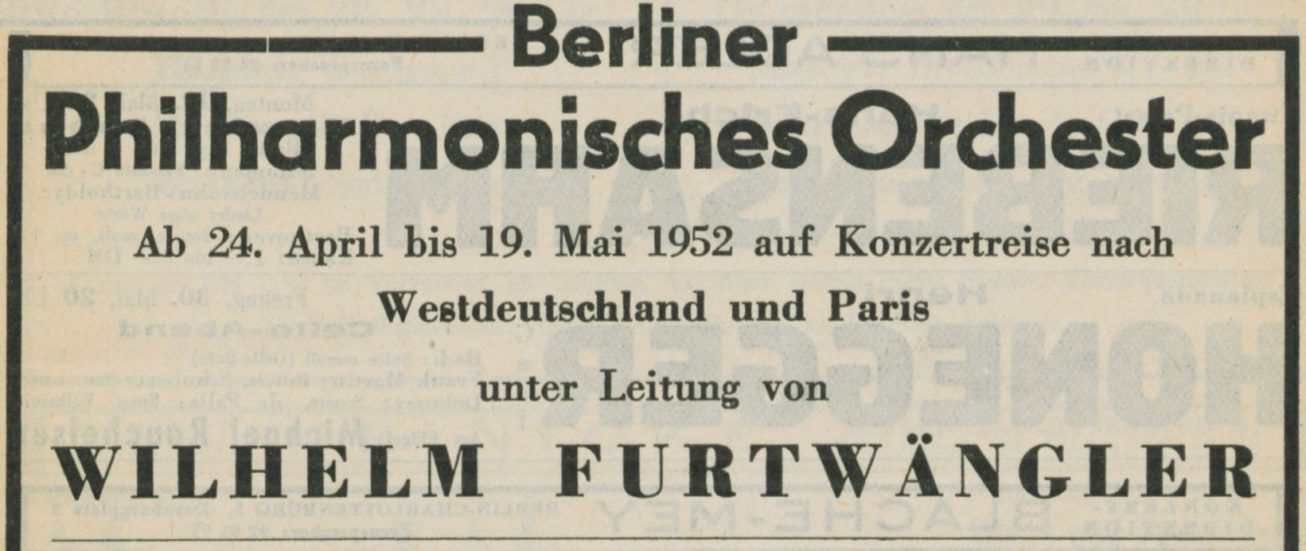

Avec le Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) de retour d’une tournée qui s’est déroulée entre le 24 avril et le 19 mai 1952, ils ont joué ce Concerto au Titania Palast de Berlin le 24 mai avant de l’enregistrer les 25 et 26 à la Jesus-Christus Kirche, salle utilisée habituellement par la Deutsche Grammophon et la RIAS.

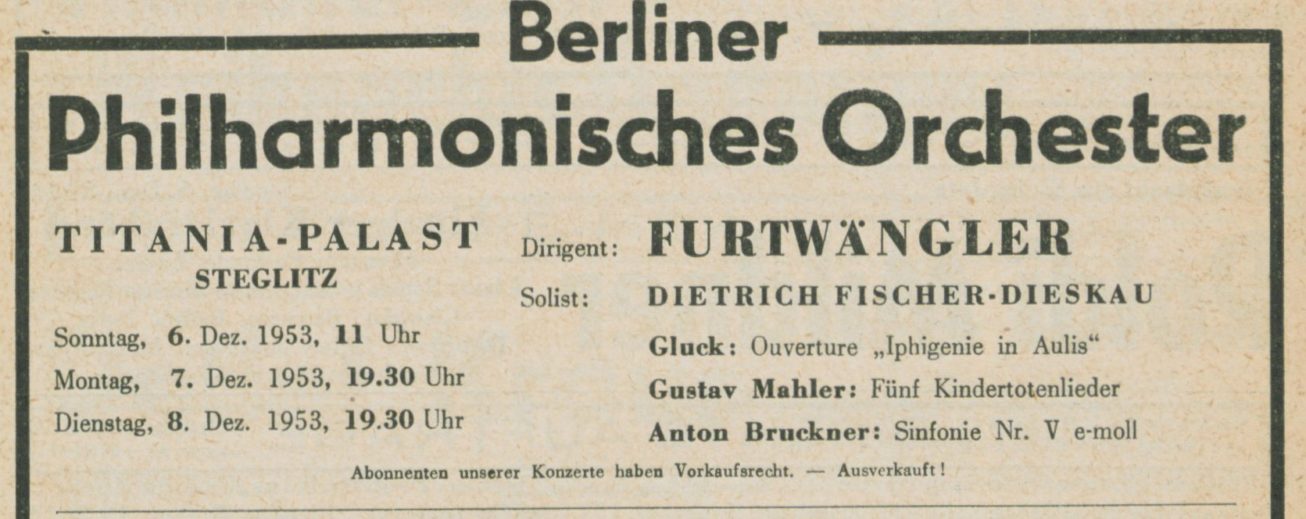

C’était la première fois qu’après la guerre EMI enregistrait Furtwängler à Berlin. Il y eut ensuite un autre enregistrement berlinois, à savoir l’Ouverture de ‘Leonore II’ de Beethoven les 4 et 5 avril 1954 à la Musikhochschule, avec cette fois une équipe d’enregistrement allemande (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), peut-être un test annonciateur d’un changement de politique discographique qui n’a malheureusement pas pu se concrétiser en raison du décès du chef d’orchestre. On peut penser en effet qu’EMI aurait souhaité enregistrer l’année suivante avec Furtwängler et le BPO les Kindertotenlieder de Mahler avec Fischer-Dieskau (l’œuvre a été jouée à Berlin en décembre 1953, et un enregistrement à Londres en mars 1954 avec le Philharmonia a été annulé) ainsi que le Deutsches Requiem de Brahms avec Grümmer et Fischer-Dieskau, deux projets qui ont été confiés in fine à la direction de Rudolf Kempe.

Menuhin and Furtwängler performed Mendelssohn’s Concerto Op.64 together for the first time on 29 September 1949 at London’s Royal Albert Hall with the Wiener Philharmoniker.

With the Berliner Philharmoniker (Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester) on their return from a tour that lasted from 24 April to 19 May 1952, they played this Concerto at the Titania Palast in Berlin on 24 May before recording it on 25 and 26 May at the Jesus-Christus Kirche, a venue known as being used by Deutsche Grammophon and RIAS.

It was the first time after the war that EMI recorded Furtwängler in Berlin. There was later another recording in Berlin, Beethoven’s Overture ‘Leonore II’ on April 4 and 5 1954 at the Musikhochschule, this time with a German recording team (Prod: Fritz Ganss: Eng: Horst Lindner), maybe a test which heralded a change in recording policy that unfortunately could not materialise due to the conductor’s death. Indeed, one might think that EMI would have liked to record the following year with Furtwängler and the BPO Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with Fischer-Dieskau (the work was performed in Berlin in December 1953, and a recording in London in March 1954 with the Philharmonia had been cancelled) as well as Brahms’ Deutsches Requiem with Grümmer and Fischer-Dieskau, two projects that were ultimately entrusted to Rudolf Kempe.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

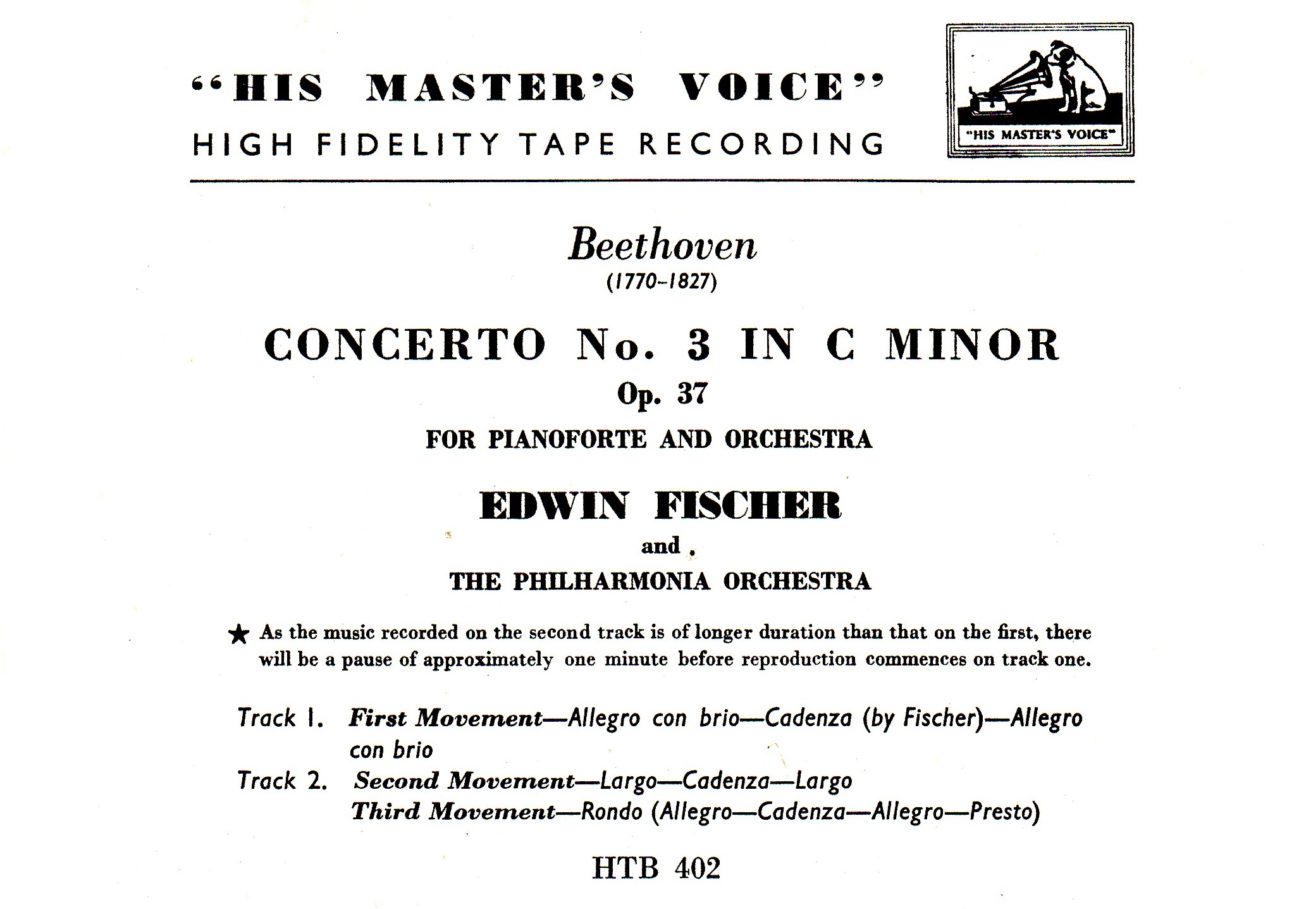

Fischer – Philharmonia Orchestra – Beethoven Concerto n°3 Op. 37

London Kingsway Hall – 7 & 14 mai 1954

Prod: Walter Jellinek & Alec Robertson – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips HTB 402

Nous vous avons déjà proposé cet enregistrement à partir de la même source. En voici le lien:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

La bande étant selon le standard CCIR, il a fallu tenir compte de la différence entre les courbes d’égalisation de la bande (CCIR) et le magnétophone (NAB) sur laquelle elle était lue. A l’époque, cette égalisation n’a pu être faite que de manière approximative et le son obtenu accentuait les duretés de la prise de son, surtout sur l’orchestre. Avec une meilleure égalisation, le son est maintenant plus musical, sans que l’on perde pour autant les détails de l’interprétation.

We have already offered you this recording from the same source. Here is the link:

https://concertsarchiveshd.fr/fischer-philharmonia-orchestra-beethoven-concerto-pour-piano-n3-op-37/

As the tape was in the CCIR standard, it was necessary to take into account the difference between the equalisation curves of the tape (CCIR) and of the tape recorder (NAB) on which it was played. At the time, this equalisation could only be done approximately and the sound obtained accentuated the harshness of the recording, especially on the orchestra. With better equalisation, the sound is now more musical, without losing any of the details of the performance.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

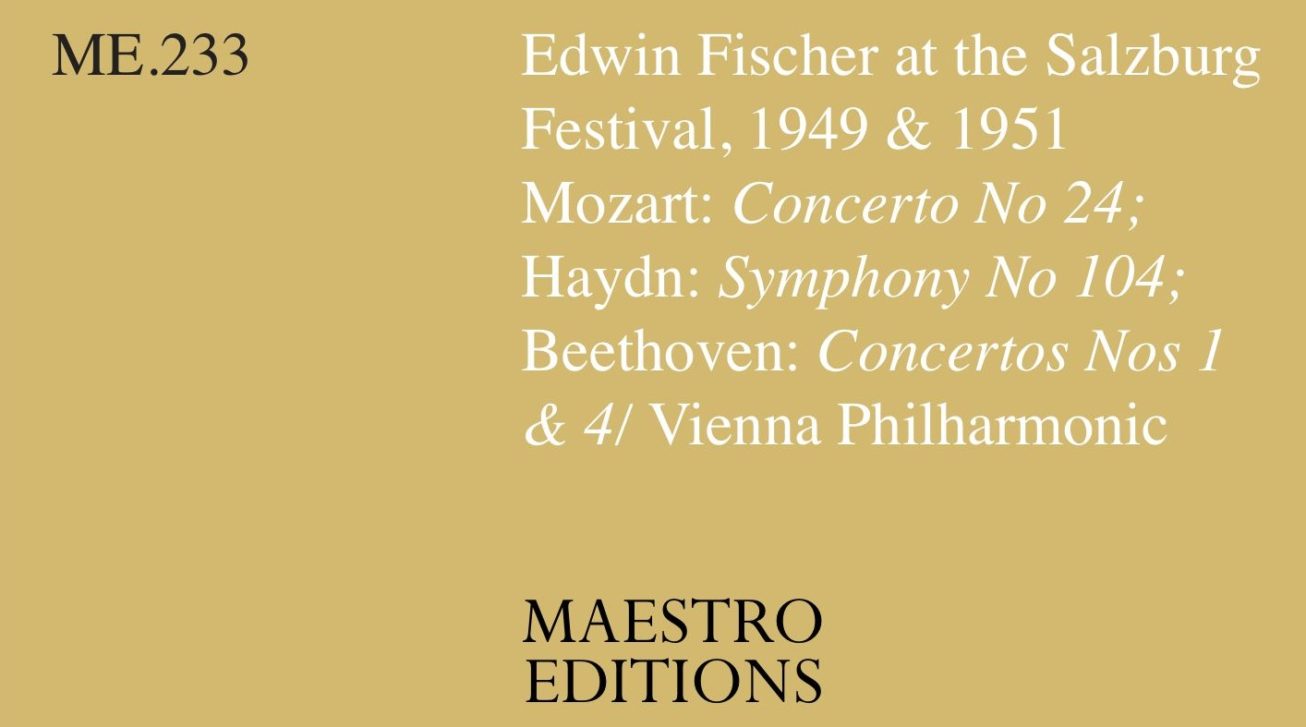

Maestro Editions qui a déjà publié le concert dirigé par Edwin Fischer lors du Festival de Strasbourg 1953, nous offre des inédits d’importance provenant cette fois du Festival de Salzbourg, où Fischer dirige les Wiener Philharmoniker. Il s’agit de la totalité du concert du 30 juillet 1951 (Mozart Concerto n°24 K.491, Haydn Symphonie n°104 et Beethoven Concerto n°1 Op.15) et du seul enregistrement qui subsiste du concert du 1er août 1949 (Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58).

Pour plus de détails, suivez ce lien:

Maestro Editions, which has already published the concert conducted by Edwin Fischer at the 1953 Strasbourg Festival, is now offering us some important previously unreleased material from the Salzburg Festival, where Fischer conducts the Wiener Philharmoniker. It is comprised of the entire concert of 30 July 1951 (Mozart Concerto No. 24 K.491, Haydn Symphony No. 104 and Beethoven Concerto No. 1 Op.15) and of the only surviving recording of the concert of 1 August 1949 (Beethoven Concerto No. 4 Op.58).

For more information, follow this link:

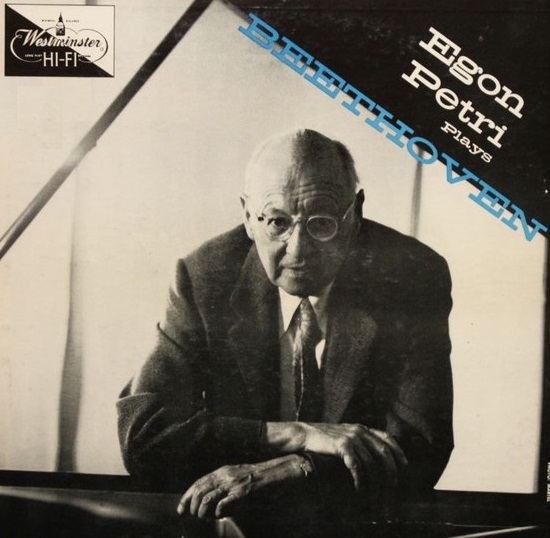

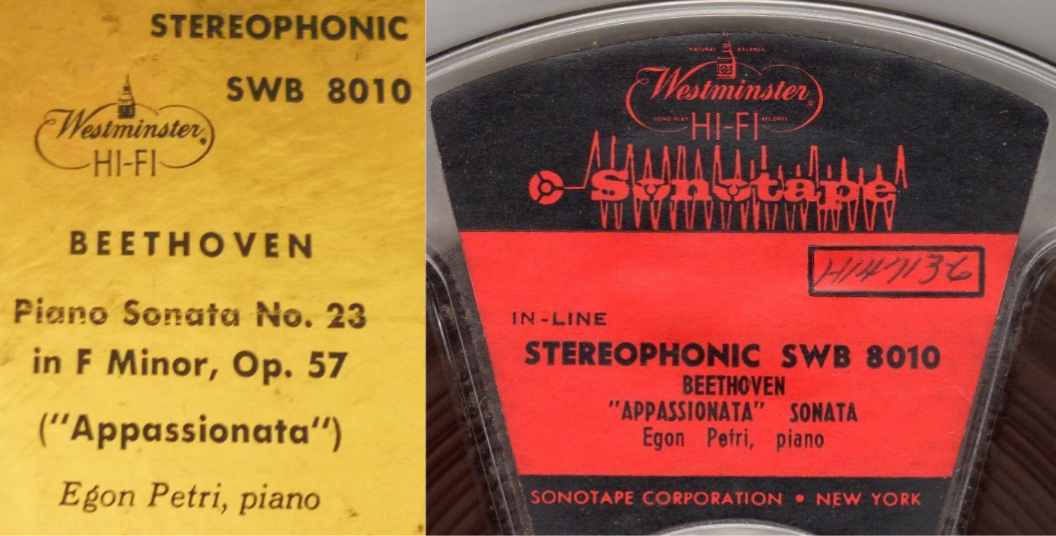

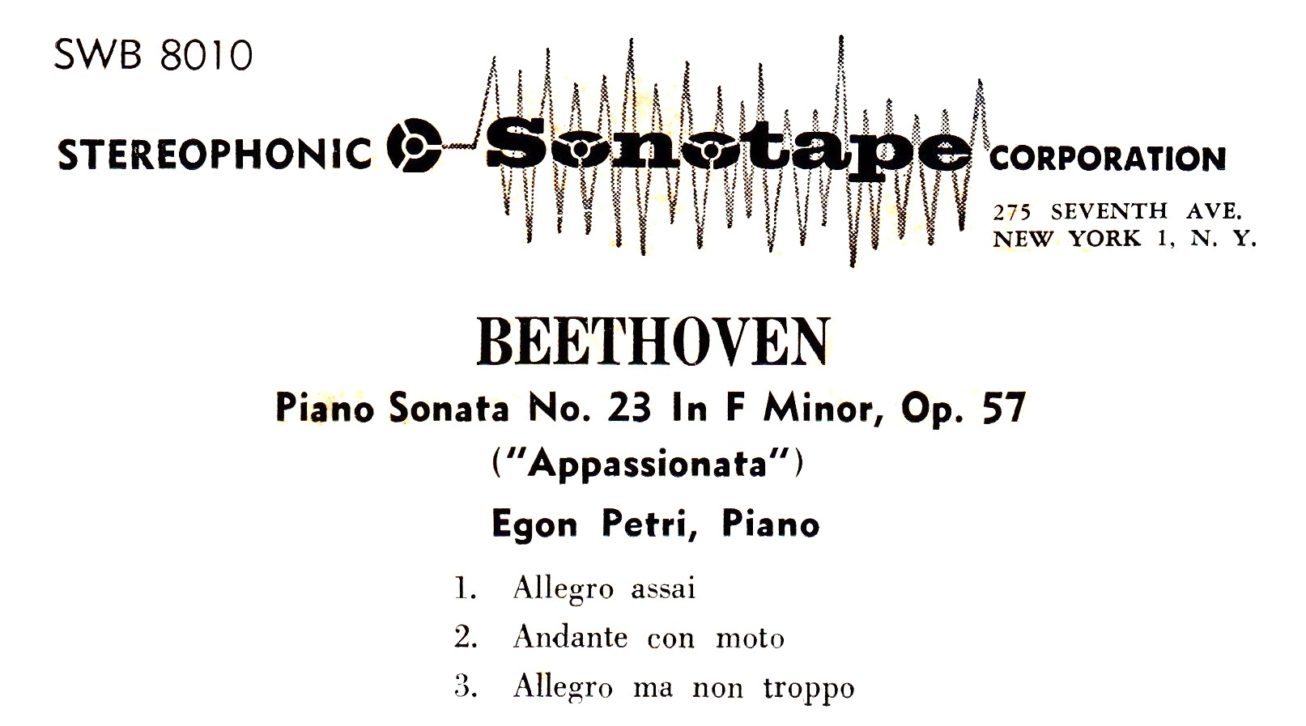

Petri – Beethoven Sonate n° 23 Op. 57

Egon Petri, piano

Beethoven Sonate n°23 Op.57

New York – June 11, 1956

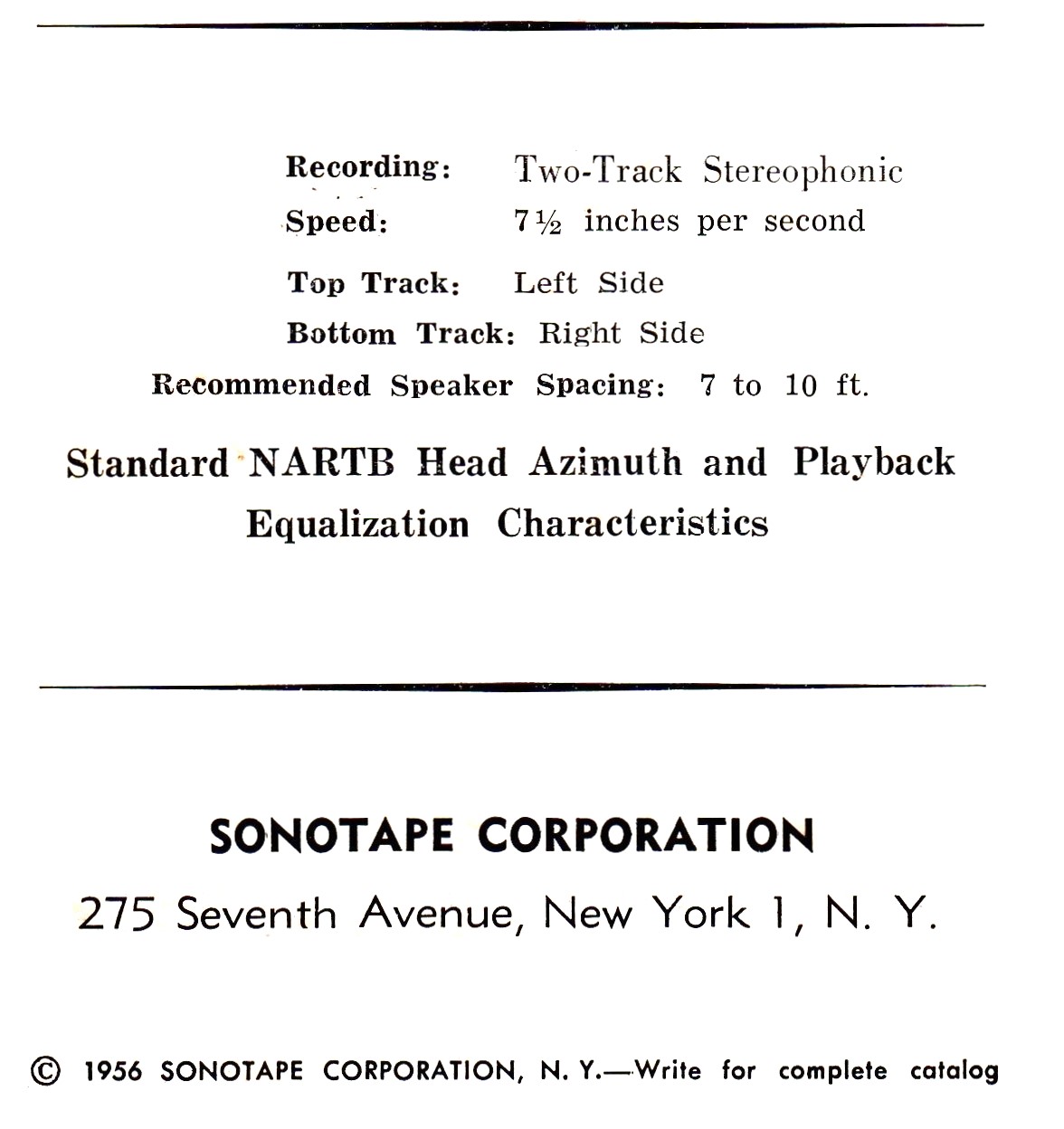

Source Bande/Tape Westminster Sonotape SWB 8010: 2 pistes/19 cm/s / 2 tracks /7.5 ips STEREO

Egon Petri (1881-1962) est né à Hanovre dans une famille néerlandaise. Il a été élevé à Dresde où son père, le violoniste Henri Petri, était le Konzertmeister de la célèbre ‘Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden’. Il a commencé par étudier le violon, puis le piano, pour lequel l’influence principale a été celle du compositeur Ferruccio Busoni, un ami de son père, dont il est devenu un disciple.

Dans les années 1920, Egon Petri a enseigné à Berlin, puis en Pologne jusqu’en 1939, avant de partir pour les États-Unis en laissant derrière lui tous ses biens. Il a été naturalisé américain en 1955.

Il a commencé à faire des disques en 1929 et bien qu’au cours des années 1950, il ait sérieusement réduit son activité, il a laissé des enregistrements en studio et en concert jusqu’en 1960, et en 1959, il a même joué en public les 32 Sonates de Beethoven. La Sonate n°23 de Beethoven est un des enregistrements stéréo qu’il a faits pour la firme Westminster. Petri était connu notamment pour l’ampleur et la beauté du son de son piano, et il a été fort bien capté lors de ces séances.

Egon Petri (1881-1962) was born in Hanover into a Dutch family. He was raised in Dresden, where his father, the violinist Henri Petri, was Konzertmeister of the famous ‘Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden’. He first studied the violin, then the piano, for which his main influence was the composer Ferruccio Busoni, a friend of his father, of whom he became a disciple.

In the 1920s, Egon Petri taught in Berlin, then in Poland until 1939, before moving to the USA, leaving all his possessions behind. He became a naturalized American citizen in 1955.

He began making records in 1929, and although in the 1950s he seriously curtailed his activity, he left studio and concert recordings until 1960, and in 1959, he even gave a complete public performance of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas. Beethoven’s Sonata n°23 is one of the stereo recordings he made for the Westminster label. Petri was known in particular for the breadth and beauty of his piano sound, and it was well captured during these sessions.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment