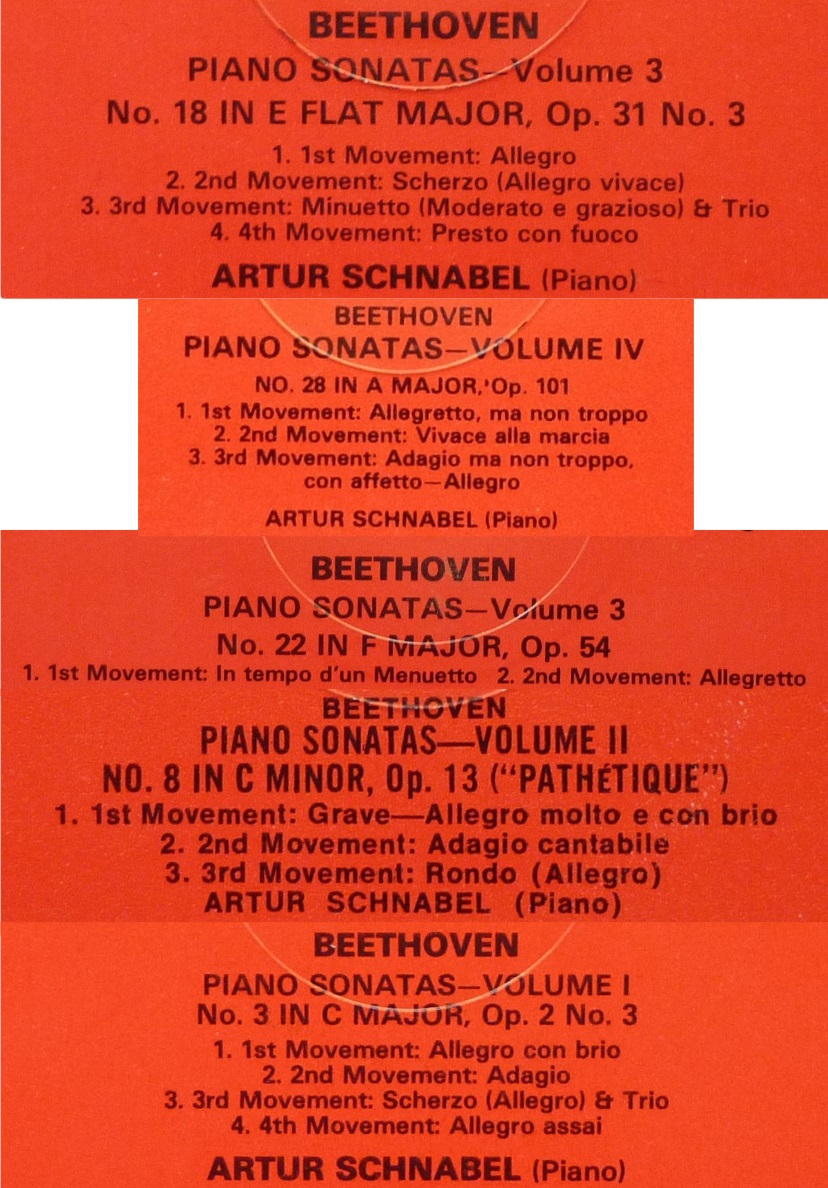

Étiquette : Beethoven

Sonate n°18 Op.31 n°3: 25 Mars 1932

Sonate n°28 Op.101: 24 Avril 1934

Sonate n°22 Op.54: 11 Avril 1933

Sonate n°8 Op.13: 2 Octobre 1933; 23 Avril 1934

Sonate n°3 Op.2 n°3: 26&27 Avril 1934

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n° 3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

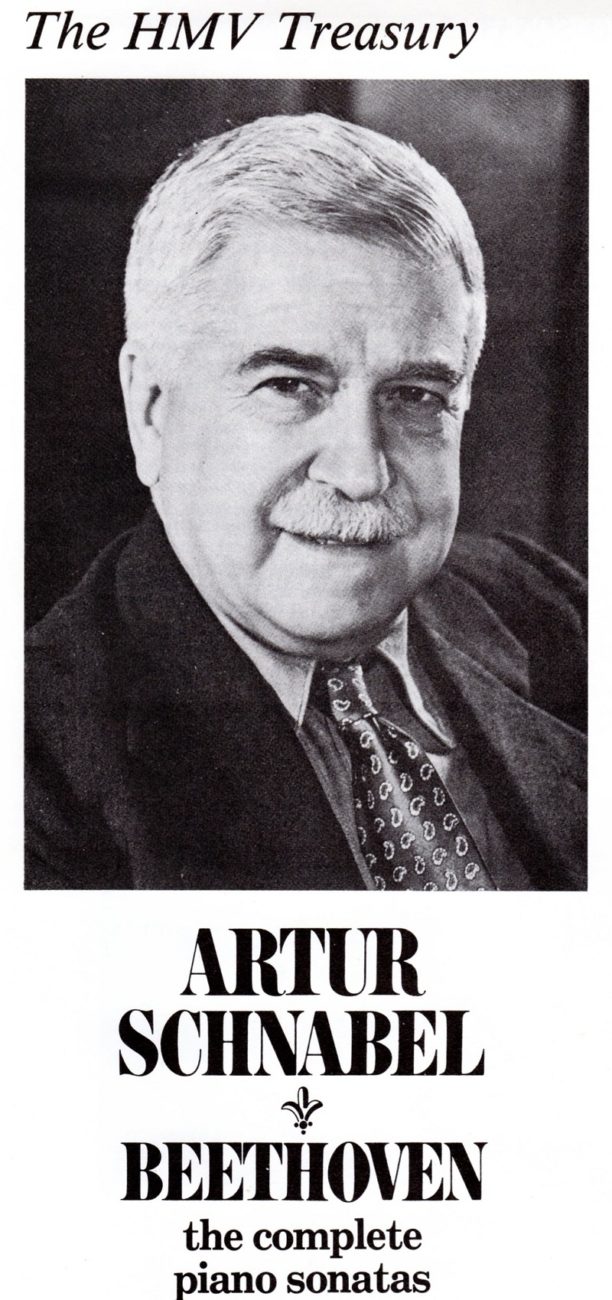

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le deuxième programme de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comportait les cinq sonates ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Pour le deuxième concert (22 janvier) de l’intégrale donnée à Carnegie Hall en 1936, nous disposons de la critique d’Howard Taubman qui va pour l’essentiel dans le même sens que son confrère Olin Downes: Il souligne tout d’abord à quel point l’oreille était réjouie par une richesse de phrasés, de nuances et de dynamique tout le long de chaque œuvre, que cependant l’auditeur n’avait jamais son attention détournée par des fragments, mais qu’il était conduit à voir toute la logique de chaque composition. Il note également que la réussite de ce récital ne pouvait que rendre difficile de soutenir l’objection de certains que les interprétations de Schnabel seraient trop intellectuelles, et que l’émotion en serait évacuée par la prééminence de la tête sur le cœur, car il à joué avec brillance et tempérament. Et que si le pianiste ne laissait pas libre cours à son tempérament, c’était pour de bonnes raisons.

« La sonate dite « Pathétique » (n°8 Op.13) a été jouée avec incandescence, sans qu’elle puisse virer à la sentimentalité. La sonate en mi bémol majeur (n°18 Op.31 n°3) était vibrante, et pleine de brio. Et pour une pleine compréhension de la profondeur de l’imagination de M. Schnabel, il faut mentionner la grandeur et la noblesse de son jeu dans l’Op.101 (n°28). Le public a une nouvelle fois écouté dans un silence qu’on ne rencontre que lors d’événements rituels comme le cycle Wagner en matinée au Metropolitan. »

Artur Schnabel’s second program of the complete Beethoven sonatas was comprised of the above mentioned five sonates, two of which being played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

For the second concert (22 January) of the complete performance of the 32 Sonatas given at Carnegie Hall in 1936, we have an article by Howard Taubman who basically shares the view of his associate Olin Downes: He underlines in the first place that the ear caught innumerable felicities of phrase, nuance and dynamics, as a work pursued its course and that the auditor nevertheless was never deterred by fragments, but compelled to see the complete logic of each composition. Objecting to his interpretations on the ground that they are intellectualized and that the emotion is wrung out by the predominence of the head over the heart is a thesis difficult to defend in the face of last night’s accomplishment. For Mr. Schnabel played with brilliance and temperament. True, his temperament was held in leash, and with good reasons.

« The sonata known as the « Pathétique » (n°8 Op.13) was played with enkindling warmth but it was not permitted to deteriorate into sentimentality. The E flat major sonata (n°18 Op.31 n°3) was vibrant, full of gusto. For a full comprehension of the profundity of Mr. Schnabel’s imagination, one must speak of the grandeur and nobility of his playing of Op.101 (n°28). The audience again observed the hushed attention that is only perceptible at ritual events like the Wagner matinee cycle at the Metropolitan. »

Sonate n° 15 Op.28: 3 & 17 Février 1933

Sonate n°31 Op.110: 21 Janvier 1932 (premier enregistrement de Schnabel)

Sonate n°1 Op.2 n°1: 23, 24 & 28 Avril 1934

Sonate n°16 Op.31 n°1: 5 & 6 Novembre 1935; 15 Janvier 1937 (face 4)

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n° 3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

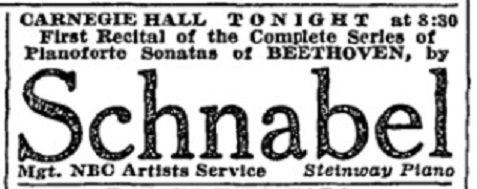

Artur Schnabel a non seulement enregistré entre 1932 et 1935 la toute première intégrale des 32 Sonates pour piano de Beethoven, mais, à quatre reprises, il les a aussi jouées au concert à Berlin en janvier-février 1927, à Londres en octobre-novembre 1932, de nouveau à Berlin en janvier-avril 1933 et enfin à New York en janvier-février 1936, sous forme de cycles de sept récitals toujours composés de la même façon, chaque récital panachant soit quatre, soit cinq, sonates de différentes périodes. Pour plus de détails, cliquer ICI

Nous vous proposons d’écouter son intégrale enregistrée en reprenant le programme de chacun de ces sept récitals.

Pour le premier de ces programmes, nous disposons d’une critique tout à fait remarquable, un modèle du genre, écrite par Olin Downes après le récital à Carnegie Hall du 15 janvier 1936:

Downes mentionne tout d’abord que le public était composé en majorité de musiciens, d’étudiants et de mélomanes avertis et que de nombreux spectateurs suivaient attentivement sur la partition. Concernant le pianiste, il mentionne son sens de la grande ligne mais aussi du moindre détail, ainsi que la perfection des proportions, la profondeur de pensée et l’authenticité des sentiments qu’il projette, et enfin la simplicité sans ostentation de sa tenue en scène.

Il souligne que la musique est projetée avec une extraordinaire signification, car chaque sonate, qui est un monde en soi, est traitée comme telle en fonction de la nature de la musique et de la période qu’elle représente dans l’évolution de la pensée Beethoven. Et que cette communication s’établit sans que Schnabel ait jamais besoin « d’élever la voix du piano », car le timbre du piano et la pensée musicale se projettent dans le vaste espace de Carnegie Hall, grâce à une gamme de nuances très finement ajustée. Il note un remarquable degré de différentiation entre des accords « mezzo-piano » et « piano », entre le niveau dynamique de chaque note d’une courte phrase expressive ainsi que des gradations de tempo tout aussi subtiles, comme lors de la dernière apparition du thème dans le mouvement lent de la sonate dite « Pastorale » (n°15 Op.28).

Il note aussi l’objectivité de Schnabel, comme s’il nous disait: « Voici une sonate de Beethoven, et pour autant que j’aie pu le découvrir au cours d’une vie d’étude, c’est comme ceci que Beethoven voulait qu’elle sonne. Je le tiens de la partition de Beethoven que j’ai examinée dans toutes les versions, manuscrites et imprimées et dont ma propre édition énonce mes conclusions« . Ce que décrit ainsi Downes, c’est la filiation de Schnabel, qui composait de la musique atonale, non avec le romantisme, mais avec Arnold Schoenberg.

Concernant le programme joué ce soir là, Downes note de nouveau que chaque sonate y avait son propre style, et que la tranquillité de la sonate n°15 Op.28 qui ouvrait le concert constituait un prélude particulièrement approprié à la rhapsodie démoniaque et mystique de l’Op.110 (n°31), peut-être la plus mystérieuse de tout le cycle, dans laquelle Beethoven rêvait des rêves et avait des visions.

« Quant à la sonate n°1 Op.2 n°1, elle a été jouée avec la pleine prémonition de son caractère prophétique, mais sans exagération. Le mouvement lent a été chanté avec un parfait cantabile et un legato qu’on n’imaginerait pas au clavecin, mais avec une grâce mozartienne et une simplicité dans l’accentuation. Le Finale était plus qu’une prémonition du Beethoven en devenir, et du développement du mouvement romantique de la musique pour piano. Chaque sonate a été saluée par de longs applaudissements. »

La réédition de ces enregistrements a toujours été problématique en raison de l’adoption systématique par les éditeurs d’un filtrage du bruit de fond des 78 tours, qui se fait toujours aux dépens de la musicalité (nuances, phrasés, timbres et dynamique). Toutefois, en 1980/81, à l’occasion du Centenaire de la naissance de Schnabel, une série d’albums 33 tours sous le label « The HMV Treasury » a remarquablement restitué ces interprétations à partir de nouveaux reports effectués par Keith Hardwick dans les Studios d’Abbey Road à partir de pressages vinyle des matrices métalliques d’origine, dépourvus des bruits de surface des disques 78 tours commerciaux. Les éditions successives en CD (EMI et Warner) ont été décevantes à cause de l’usage systématique d‘un filtrage excessif. D’autres éditeurs (Pearl, Naxos) ont obtenu de meilleurs résultats à partir de 78 tours commerciaux, sans toutefois égaler les Albums « The HMV Treasury ».

____________

Sonata n° 15 Op.28: 3 & 17 February 1933

Sonata n°31 Op.110: 21 January 1932 ( Schnabel’s first recording)

Sonata n°1 Op.2 n°1: 23, 24 & 28 April 1934

Sonata n°16 Op.31 n°1: 5 & 6 November 1935; 15 January 1937 (side 4)

London Abbey Road Studio n° 3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano Bechstein

Source: LPs « The HMV Treasury »

Artur Schnabel has not only made between 1932 and 1935 the very first complete recording of the 32 piano Sonatas, but he also performed them four times during concert cycles in Berlin in January-February 1927, in London in October-November 1932, again in Berlin in January-April 1933 and lastly in New York in January-February 1936, each cycle of seven recitals always organized in the same way, each recital being comprised of either four or five Sonatas from different periods. For a detailed description, click HERE

We propose you to listen to his complete recording according to the program of each of these seven recitals.

For the first of these programs, we have an outstanding article, indeed a model, written by Olin Downes after the Carnegie Hall recital of 15 January 1936:

To start with, Downes mentions that the majority of the public consisted of musicians, students and serious music lovers and that a great many in the audience had scores to follow every note of the interpretations. As to the pianist, he notes his sense of the grand line and of the most significant finish of detail, as well as the perfect proportion, the depth of thought and the genuineness of feeling he conveys, but also his unostentasious manner and his simplicity on the platform.

He underlines that the music is projected with extraordinary significance. As each sonata is a different world in itself, so does the treatment of each one vary in accordance with the nature of the music and the period that it represents in Beethoven’s thought. And he establishes this communication never by « raising the piano’s voice », because the tone carries and the musical thought carries in the wide spaces of Carnegie Hall, and this by means of a very finely adjusted scale of values. He notes a remarkable degree of difference between chords « mezzo-piano » and « piano », between the dynamic value of each note of a short expressive phrase, as well as equally subtle gradations of tempo, witness the last appearance of the theme of the slow movement of the so-called « Pastoral »sonata (n°15 Op.28).

He also notes Schnabel’s objective vein, seeming to say: « This is Beethoven‘s sonata, so far as I have been able to discover in a lifetime of study, it is precisely as Beethoven wanted it to sound. My authority is Beethoven’s score which I have examined in all the existing manuscript and printed versions of which my own edition states my conclusions« . What Downes thus describes is the direct line of Schnabel, who composed atonal music, not with romantiscm, but with Arnold Schoenberg.

As to the program performed that evening, Downes notes again that each sonata had its special style, and that the tranquillity of sonata n°15 Op.28 that opened the concert made a particularly felicitious prelude to the demoniac and mystical rhapsody of the Op.110 (n°31), perhaps the most mysterious of the whole set, wherein Beethoven dreamed dreams and had visions.

« The sonata n°1 Op.2 n°1 was performed with the fullest realization of its prophetic character, but without forcing this note. The slow movement was sung with an immaculate cantilena and a legato that it would be hard to conceive as issuing from the harpsichord, yet with a Mozartian grace and simplicity of accent. The Finale was more than a premonition of the Beethoven to come, and indeed of the course of the romantic movement in piano music. There was long applause after each sonata. »

The reissue of these recordings was always problematic because of the systematic use by the editors of noise reduction to filter the background noise of the 78rpm, always detrimental to musicality (details, phrasings, timbres and dynamics). However, in 1980/81, with a view to celebrating the Centenary of Schnabel’s birth, a series of LP Albums under the label « The HMV Treasury » has remarkably restored these performances from fresh transfers made by Keith Hardwick at the Abbey Road Studios from vinyl pressings of the original metal parts, devoid of the background noise of the commercial shellack 78rpm. The later CD issues (EMI et Warner) were a failure because of the systematic use of excessive filtering. Other firms (Pearl, Naxos) obtained better results from commercial shellack pressings, without however matching the « The HMV Treasury » Albums.

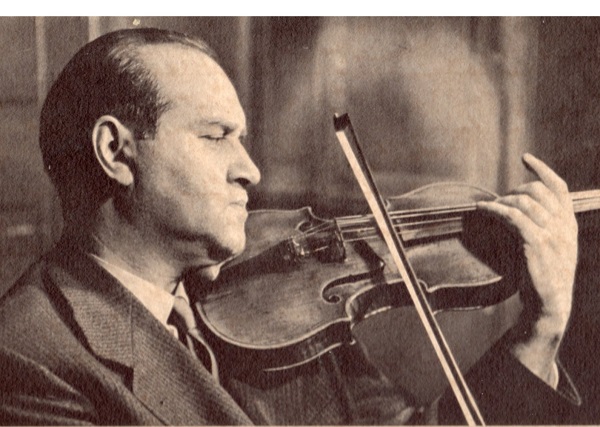

Sonate n°1 Op.12 n°1: Vladimir Yampolsky, piano (Prague 26 avril 1954) Supraphon ALPV 244

Sonate n°3 Op.12 n°3: Vladimir Yampolsky, piano (Bruxelles 19 &20 mai 1955) Angel 35331

Sonate n°4 Op.23: Alexander Goldenweiser, piano (Moscou 17 avril 1950) Akkord D-07893

Sonate n°5 Op.24: Lev Oborin, piano (Moscou 1950) Akkord D-07894

Lev Oborin, Alexander Goldenweiser & Vladimir Yampolsky

David Oïstrakh, né à Odessa (Ukraine) en 1908 et décédé à Amsterdam (Pays-Bas) en 1974, a enregistré à Paris en mai-juin 1962 avec le pianiste Lev Oborin (1907-1974) une célèbre intégrale des Sonates violon-piano de Beethoven après les avoir données en concert à la Salle Pleyel. Cet ensemble a fait l’objet de nombreuses rééditions à tel point que l’on a quasiment oublié l’existence de disques antérieurs. Aussi bien ces enregistrements de studio que les enregistrements des concerts (publiés par Doremi) montrent que ces interprétations sont en retrait par rapport aux enregistrements précédents d’Oïstrakh de huit de ces sonates réalisés entre 1949 et 1955 avec au piano Vladimir Yampolsky (1905-1965) pour les sonates n°1 et 3, Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961) pour la sonate n°4 et Lev Oborin (1907-1974) pour les cinq autres (n°5, 7 , 8, 9 et 10).

Si quatre d’entre elles (n°4, 5, 7 et 8) ont été enregistrées à Moscou, les quatre autres (n°1, 3, 9 et 10) l’ont été respectivement à Prague (pour Supraphon), à Bruxelles (pour EMI), à Paris (pour Le Chant du Monde) et à New-York (pour Columbia), et cette multiplicité d’éditeurs n’a pas permis une publication globale de cette quasi-intégrale.

Or, en dépit de la présence de trois pianistes différents et d’une dispersion des dates ainsi que des lieux et donc aussi des équipes d’enregistrement, on constate une grande homogénéité entre ces interprétations, ce qui signe l’indépendance d’esprit de David Oïstrakh. Nous vous les proposons en trois groupes à partir des microsillons d’origine.

____________

David Oïstrakh, born in Odessa (Ukraine) in 1908 and deceased in Amsterdam (Netherland) in 1974, has recorded in Paris in May-June 1962 with pianist Lev Oborin (1907-1974) a well-known complete version of Beethoven’s violin-piano Sonatas shortly after a series of concerts at Salle Pleyel. It has been re-issued many times so that the very existence of earlier recordings has been almost forgotten. The studio recordings as well as the concert performances (released by Doremi) show that these are much less convincing that the earlier Oïstrakh recordings of eight of the sonatas made between 1949 and 1955 with pianists Vladimir Yampolsky (1905-1965) for sonatas n°1 and 3, Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961) for sonata n°4 and Lev Oborin (1907-1974) for the other five (n°5, 7 , 8, 9 and 10).

If four of them (n°4, 5, 7 and 8) were recorded in Moscow, the other four (n°1, 3, 9 and 10) were made in Prag (for Supraphon), in Brussels (for EMI), in Paris (for Le Chant du Monde) and in New-York (for Columbia), and this multiplicity of editors did not permit an overall re-issue of this fast complete series.

In spite of three different pianists and of a dispersion of the dates as well as of the recording countries and for that matter also of the recording teams, there is a great homogeneity in the performances which accounts for David Oïstrakh’s independent mind. We propose them in three groups from the original LPs.

David Oïstrakh & Vladimir Yampolsky

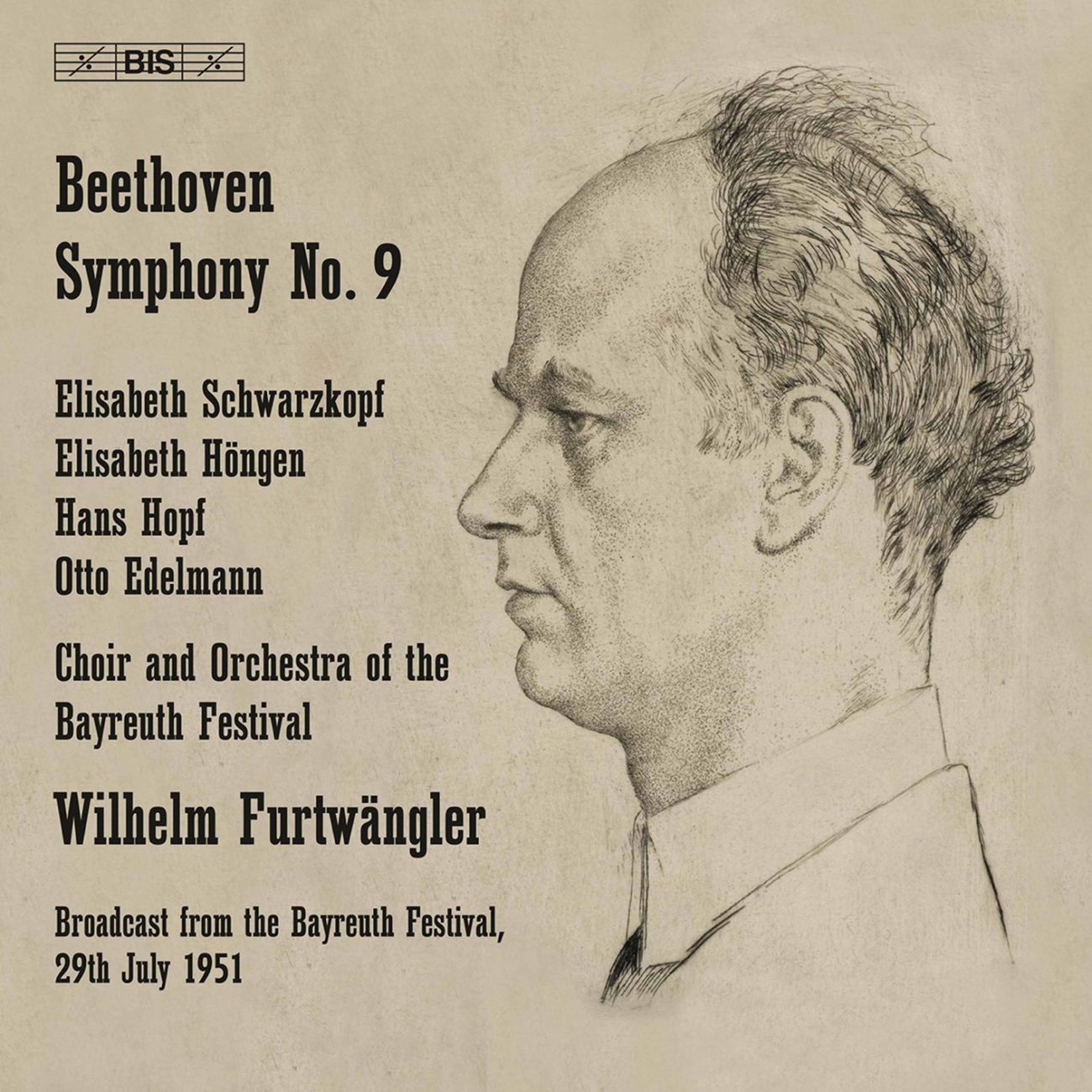

Beethoven Symphony n°9 Op125 Das Festspielorchester – Das Festspielchor Bayreuth

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen,Hans Hopf, Otto Edelmann

Dir: Wilhelm Furtwängler

La firme suédoise BIS vient de mettre en vente sous forme de SACD Hybride (BIS-9060) et de téléchargement HD la captation par la Radio Suédoise de la retransmission en direct de ce concert par la Radiodiffusion Bavaroise (Bayerischer Rundfunk), qui de manière inattendue a été conservée dans ses Archives.

Les négociations entre Wilhelm Furtwängler et Wieland Wagner préalablement à ce concert, la composition de l’orchestre et des chœurs, l’organisation des répétitions, les circonstances techniques de la retransmission et de la captation par la Radio Suédoise, ainsi que le contenu de l’enregistrement publié par EMI sont discutées dans cet article: pour le lire, cliquer ICI

The Swedish record company BIS has recently issued both as a Hybrid SACD (BIS-9060) and as a Hi-Res download (24 bits/96 KHz) the recording made by the Swedish Radio of the Bavarian radio (Bayerischer Rundfunk) live broadcast of this concert, which has unexpetedly survived in its Archives.

The negociations between Wilhelm Furtwängler and Wieland Wagner prior to the concert, how the orchestra and the choir were organized, the rehearsal plan, the technical circumstances of the broadcast and of its recording by the Swedish radio, as well as the content of the recording as published by EMI are discussed in this article: to read it, click HERE

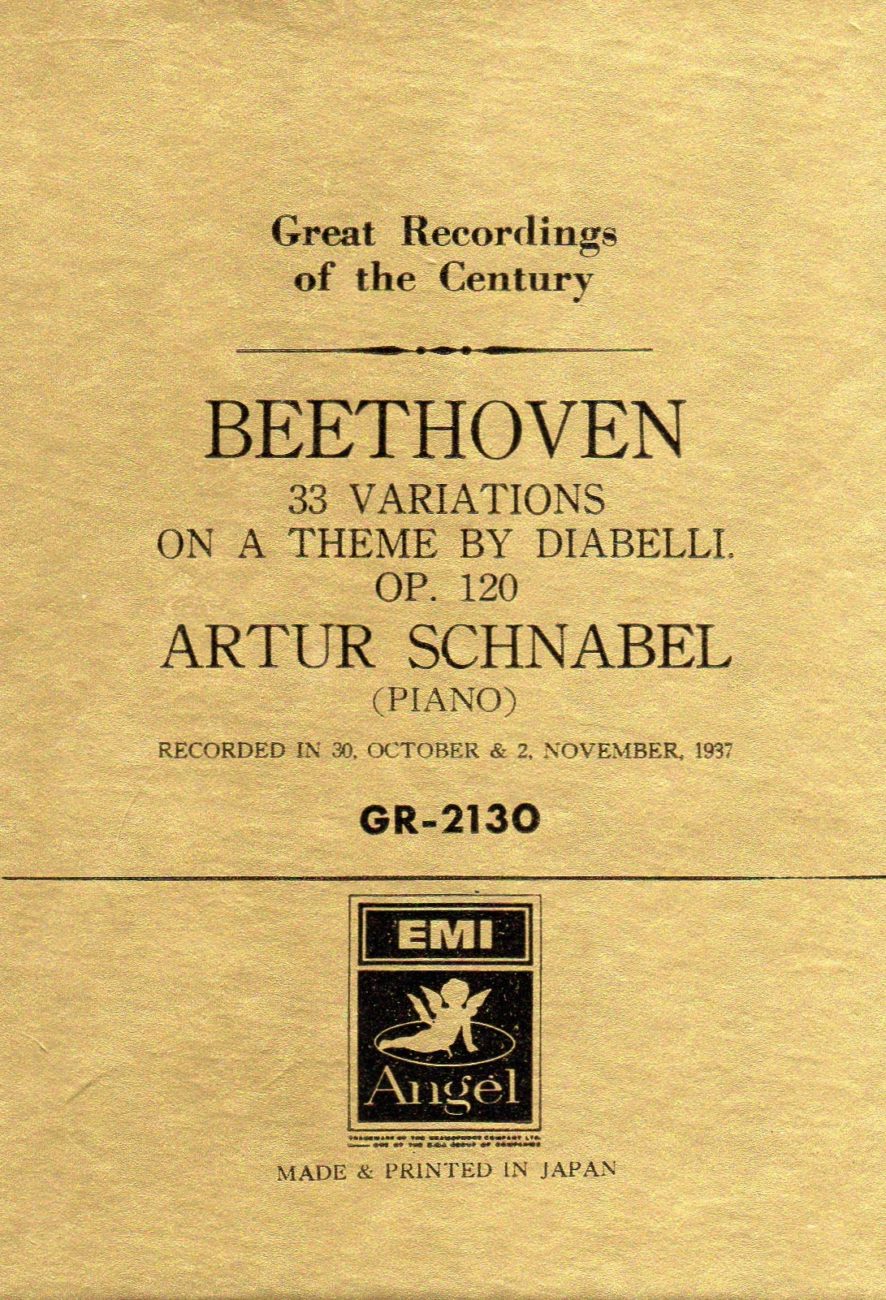

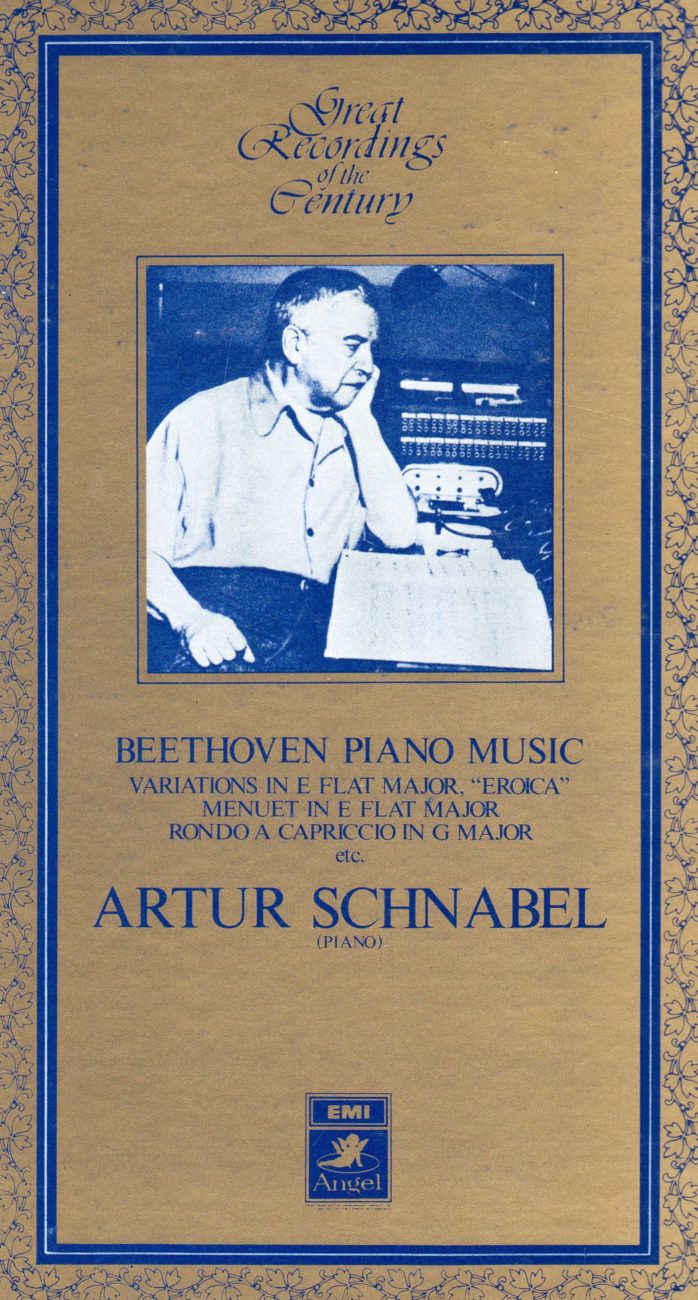

Artur Schnabel, piano Bechstein – London Abbey Road Studio n°3

Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 October 30 & November 2, 1937 (Bechstein n°560)

Variations « Eroïca » Op.35 – November, 9 1938

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Les deux microsillons EMI-Toshiba qui ont servi à cette ré-édition proviennent de reports effectués par Anthony Griffith. Réalisés à partir de pressages vinyles des matrices 78t. d’origine, ils présentent la particularité d’être peu ou pas filtrés et ainsi de nous offrir toute la palette sonore du pianiste, car la technique d’Artur Schnabel, souvent critiquée par ailleurs à cause de ses fausses notes, comportait une gamme très étendue de nuances et de gradations de toucher, de la douceur à la puissance.

La richesse d’écriture de ces variations de Beethoven permet fort heureusement à Schnabel de déployer tout l’éventail de ses qualités pianistiques.

Au cours d’une série de conférences données en 1945 à l’Université de Chicago, Schnabel a eu l’occasion, en réponse à des questions posées posées par les étudiants, d’expliquer quelle avait été sa conception du choix des pianos et de la production du son avant qu’il ne se décide à passer du Bechstein au Steinway à son arrivée aux États-Unis en 1939:

« Je dirais que la qualité qui distingue le piano de tous les autres instruments, est sa neutralité. Sur un piano, un son unique ne peut être beau; c’est la combinaison et la proportion des sons qui apporte la beauté.

Il est nécessaire de produire au moins deux ou trois sons pour donner une impression de sensualité ou pour donner à l’oreille une sensation de musique, alors que presque tous les autres instruments (sauf les instruments à percussion) ou la voix peuvent vous donner un plaisir des sens même avec un seul son. Autour de 1910, on trouvait très ‘moderne’ de dire que le piano était un instrument à percussion et que vous pouviez tout jouer staccato. Stravinsky a beaucoup fait pour la promotion de ces idées de même que de nombreux professeurs de piano, et il y avait même un livre sur ce sujet.

Une fois, un musicien m’a dit – je croyais qu’il plaisantait- que frapper le clavier avec le bout d’un parapluie ou avec le doigt ne faisait pas la moindre différence quant à la sonorité produite. C’était aussi imprimé dans ce livre – et ce n’était pas non plus une plaisanterie. Bien sûr, ça n’a aucun sens, car quiconque veut faire de la musique sait très bien tout ce qu’il peut faire avec les doigts sur le piano.

Il peut produire toutes sortes de sons: pas seulement plus ou moins forts, ou plus ou moins longs, mais aussi différentes qualités. Sur un piano, il est possible d’imiter, par exemple, le son d’un hautbois, d’un violoncelle ou d’un cor. Mais il n’est pas possible d’imiter le son d’un hautbois sur une flûte, ou d’une clarinette sur un violon; ces autres instruments conservent toujours leurs caractéristiques propres. C’est pour ça que je dis que la particularité du piano est, dans son essence, d’être le plus neutre des instruments.

Le piano Bechstein satisfaisait mieux à cette exigence de neutralité que n’importe quel autre piano que j’ai connu. Vous pouviez pratiquement tout faire sur ce piano. Le Steinway – ou plutôt le Steinway d’il y a vingt ans, car il a pas mal changé depuis – était un piano qui voulait toujours montrer quelque chose. Vous voyez, il avait beaucoup trop de personnalité propre.

Au début, quand je voulais produire quelque chose comme, disons, la voix d’un oiseau sur un Steinway, le piano sonnait toujours pour moi comme la voix d’un ténor au lieu d’un oiseau. Pendant de nombreuses années, j’ai eu le sentiment que le piano Steinway ne m’aimait pas. Une idée absurde, mais j’avais ce sentiment. Le piano Bechstein me permettait de produire des effets qui n’étaient pas possibles sur un Steinway. Le son du Steinway vibrait beaucoup plus: il a un double actionnement. Quand vous pressez très légèrement et lentement la touche d’un Steinway, elle s’arrête avant le bas, et elle a besoin d’une certaine pression, d’une seconde pression pour achever sa course vers le bas. Maintenant, j’y suis tellement habitué que cela ne m’irrite plus du tout. Au début, cependant, cela me gênait énormément: en effet, pour produire un fortissimo, vous pouvez jouer légèrement, mais si vous voulez jouer pianissimo, vous avez besoin d’utiliser beaucoup de poids sinon la touche ne descend pas. Cela semble assurément pervers. »

Both EMI-Toshiba LPs used for this re-issue come from transfers made by Anthony Griffith. Dubbed from vinyl pressings of the 78rpm metal parts, they have the particularity of having been unfiltered, or very little, and thus to offer all the pianist’s sound palette, since Artur Schnabel’s technique, otherwise often criticized because of his wrong notes, was comprised of a very extended range of nuances and touch, from softness to power.

The richness of writing of these variations by Beethoven happily allows Schnabel to show the whole spectrum of his pianistic qualities.

During a series of conferences given in 1945 at the University of Chicago, Schnabel, answering questions asked by students, had the opportunity of explaining what had been his views on the choice of pianos and on the production of sound before he decided to switch from Bechstein to Steinway when he arrived in the U-S in 1939:

« I would say that the quality which distinguishes the piano from all other instruments, is its neutrality. On a piano a single tone cannot be beautiful; it is the combination and proportion of tones which bring beauty.

You are forced to produce at least two or three tones in order to create a sensuous impression or to give a sensation of music to the ear, while almost all other instruments (except percussion instruments) or the voice can give you a sensuous pleasure even from a single tone. Around 1910 it was considered very ‘modern’ to say that the piano is a percussion instrument and that you could play everything staccato. Stravinsky did much towards promoting these ideas along with many piano teachers, and there was a book on the subject.

Once I was told by a musician—I hope he was joking—that it does not make the slightest difference for the sonority whether you strike or hit the keyboard with the tip of an umbrella or with a finger. That was also printed in that book—and not as a joke. Of course it is sheer nonsense, for everybody who wants music knows very well all that he can do with the fingers on the piano.

He can produce all kinds of tones: not only louder or softer, shorter or longer tones, but also different qualities. It is possible on a piano to imitate, for instance, the sound of an oboe, a ‘cello’, a French horn. But it is not possible to imitate the sound of an oboe on a flute, or a clarinet on a violin; these other instruments always retain their own characteristics. That is why I said that the distinction of the piano is in its being the most neutral instrument.

The Bechstein piano fulfilled this demand for neutrality better than any other piano I have known. You could do almost anything on that piano. The Steinway—or rather the Steinway of twenty years ago, for it has changed somewhat since that time—was a piano which always wanted to show something. You see, it had much too much of a personality of its own.

At first, when I wanted to produce something like, let me say, the voice of a bird on a Steinway, the piano always sounded to me like the voice of a tenor instead of a bird. For many years, I had the feeling that the Steinway piano did not like me. An absurd idea, but I had that feeling. The Bechstein piano enabled me to show effects not possible on a Steinway. The tone of the Steinway vibrated much more: it has a different action. When you push a Steinway key very lightly and slowly down, it will stop before it has reached the bottom and requires a certain pressure, a second pressure to go down all the way. This is the »double action ». By now I am so used to it that it hardly irritates me any more. At first, however, it disturbed me greatly: for in order to produce a « fortissimo » you can play lightly, but whenever you want to play « pianissimo » you have to use a great deal of weight as otherwise the key would not go down. It certainly seems perverse.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.