Étiquette : Brahms

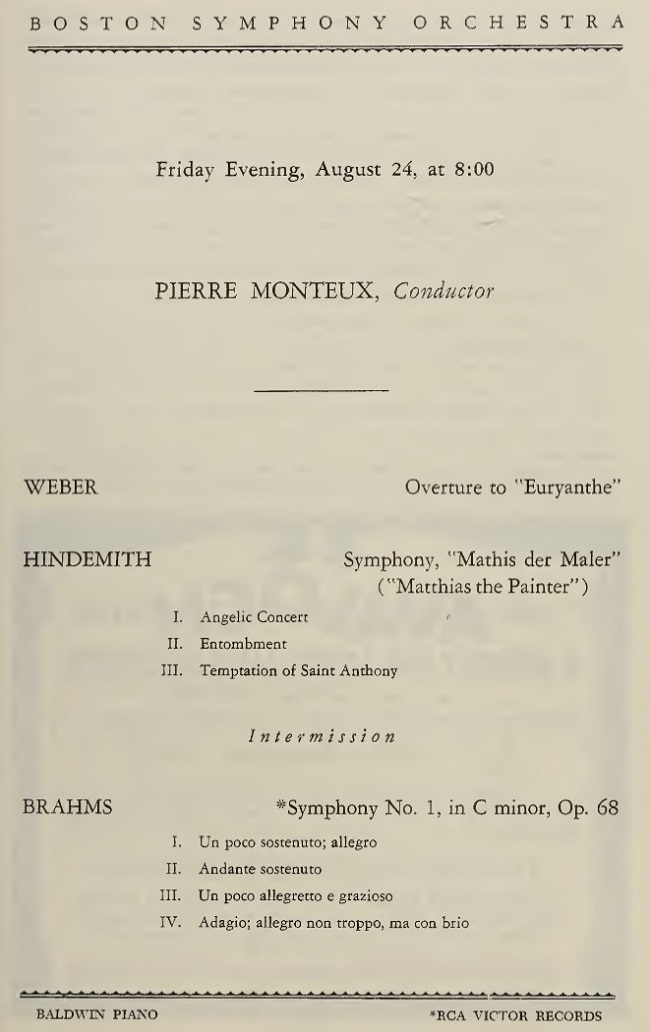

Brahms Symphony n°1 Op.68

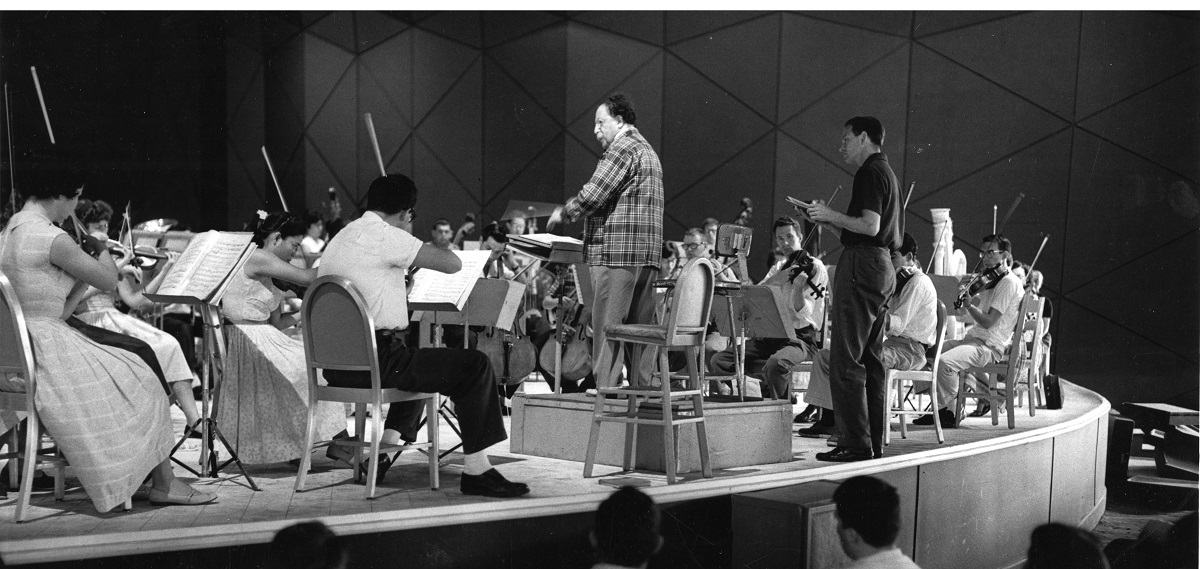

Pierre Monteux – Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)

Berkshire Festival – Tanglewood Music Shed August 24, 1962

Source: Bande/Tape: 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips STEREO

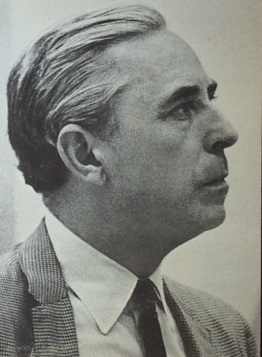

Pierre Monteux n’aimait pas être considéré comme un spécialiste de musique française, même s’il y excellait. Ce qui l’intéressait, c’était de pouvoir diriger un répertoire aussi vaste que possible, comme le montre sa discographie à condition de prendre en compte les enregistrements en public.

Une anecdote bien connue concerne le Metropolitan Opera de New York (MET). On ne lui permettait en effet d’y diriger que des opéras français et, de la même façon, les chefs italiens invités au MET devaient aussi se limiter aux opéras italiens. Un jour, il rencontra Dimitri Mitropoulos qui lui dit que, comme il était grec, et qu’il n’y avait pas d’opéra grec pouvant servir de référence, il pouvait y diriger tous les répertoires!

Monteux aimait beaucoup diriger Brahms. Au Festival de Berkshire 1962, il a donné cette interprétation chaleureuse de la ‘Première’ de Brahms, œuvre qu’il n’a pas enregistrée pour le disque.

Il faut dire que c’était une occasion très spéciale: d’une part, les deux jours suivants, Charles Munch a donné ses deux derniers concerts en tant que directeur musical du BSO, à savoir le 25 août, Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique, Debussy La Mer et Ravel Daphnis et Chloé (Suite n°2); et le 26 août, pour le dernier concert du ‘Berkshire Festival’, Copland Quiet City et Beethoven Symphonie n°9 Op.125; et d’autre part, le départ de Charles Munch signifiait aussi celui de Richard Burgin (1892–1981), qui était le ‘Concertmaster’ du BSO depuis 1920 après avoir été nommé par Monteux qui était alors Directeur Musical du BSO (1919-1924). Joseph Silvestein l’a remplacé dès le début de la saison 1962-1963. Burgin restera ‘Associate Conductor’ jusqu’en 1966.

Richard Burgin & Pierre Monteux Tanglewood 1962: les derniers concerts ensemble / the last concerts together

Pierre Monteux didn’t like to be considered a specialist in French music, even if he excelled at it. What interested him was being able to conduct as wide a repertoire as possible, as his discography shows, if you include live recordings.

A well-known anecdote concerns New York’s Metropolitan Opera (MET). He was only allowed to conduct French operas there, and similarly, Italian conductors invited to the MET had to restrict themselves to Italian operas. One day, he met Dimitri Mitropoulos, who told him that, since he was Greek, and there was no Greek opera to refer to, he could conduct all repertoires there!

Monteux loved conducting Brahms. At the 1962 Berkshire Festival, he gave this warm performance of Brahms’s ‘First’, a work of which he made no commercial recording.

It was in fact a very special occasion: on the one hand, on the following two days, Charles Munch gave his last two concerts as Music Director of the BSO: on August the 25th, Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique, Debussy La Mer and Ravel Daphnis et Chloé (Suite n°2); and on August the 26th, for the last concert of the ‘Berkshire Festival’, Copland Quiet City and Beethoven Symphony n°9 Op.125; and on the other hand, Charles Munch’s departure also meant that of Richard Burgin (1892-1981), who had been the BSO’s ‘Concertmaster’ since 1920, having been appointed by Monteux, who was then Music Director of the BSO (1919-1924). Joseph Silvestein replaced him at the start of the 1962-1963 season. Burgin remained Associate Conductor until 1966.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

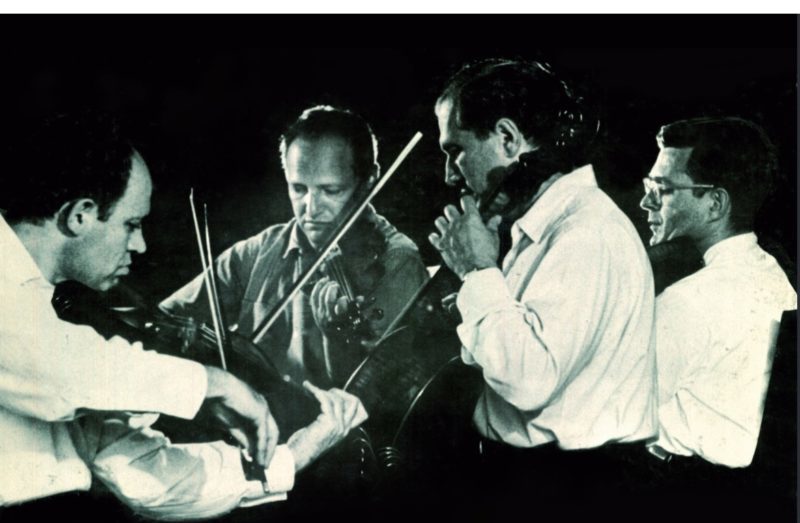

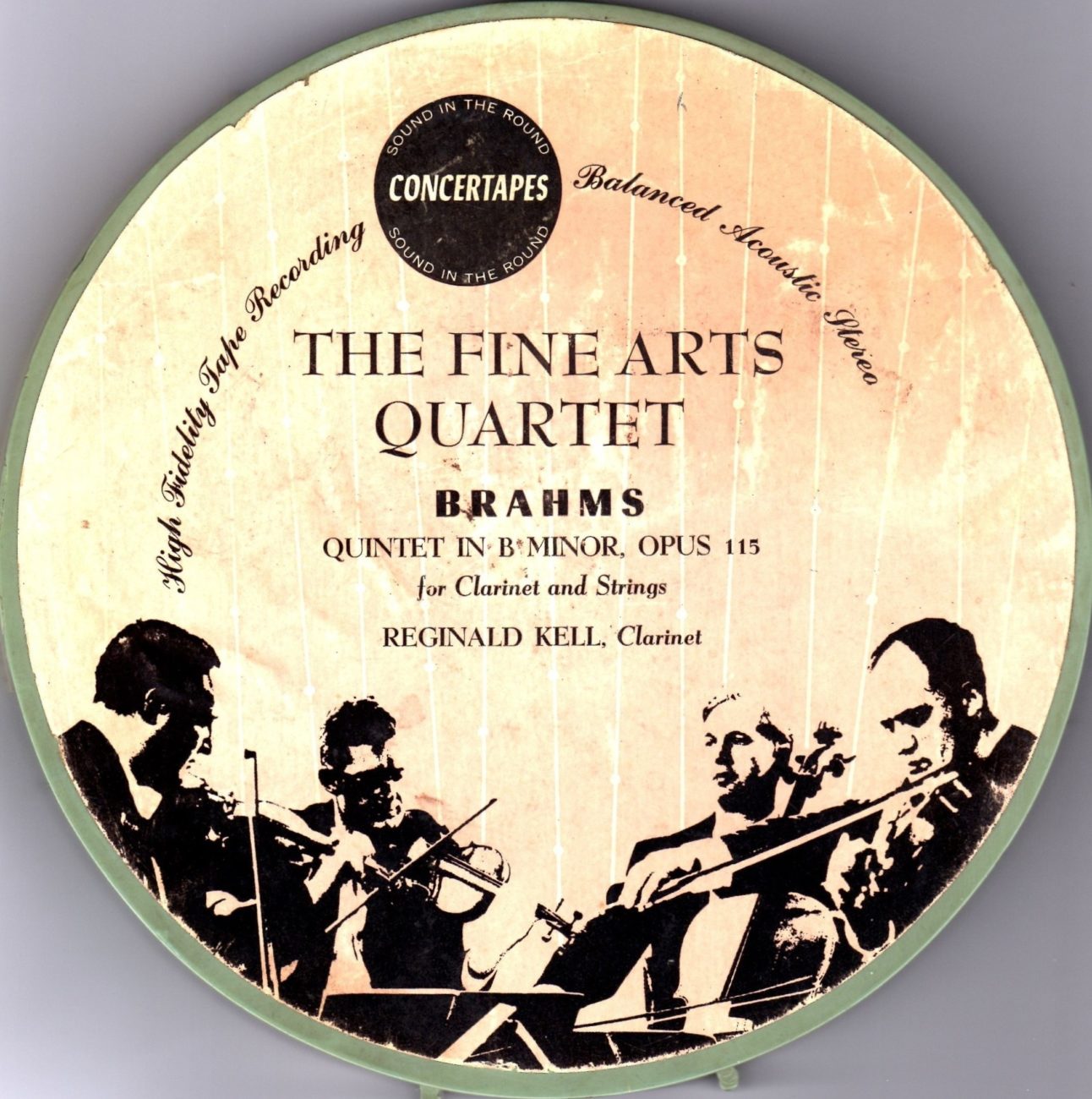

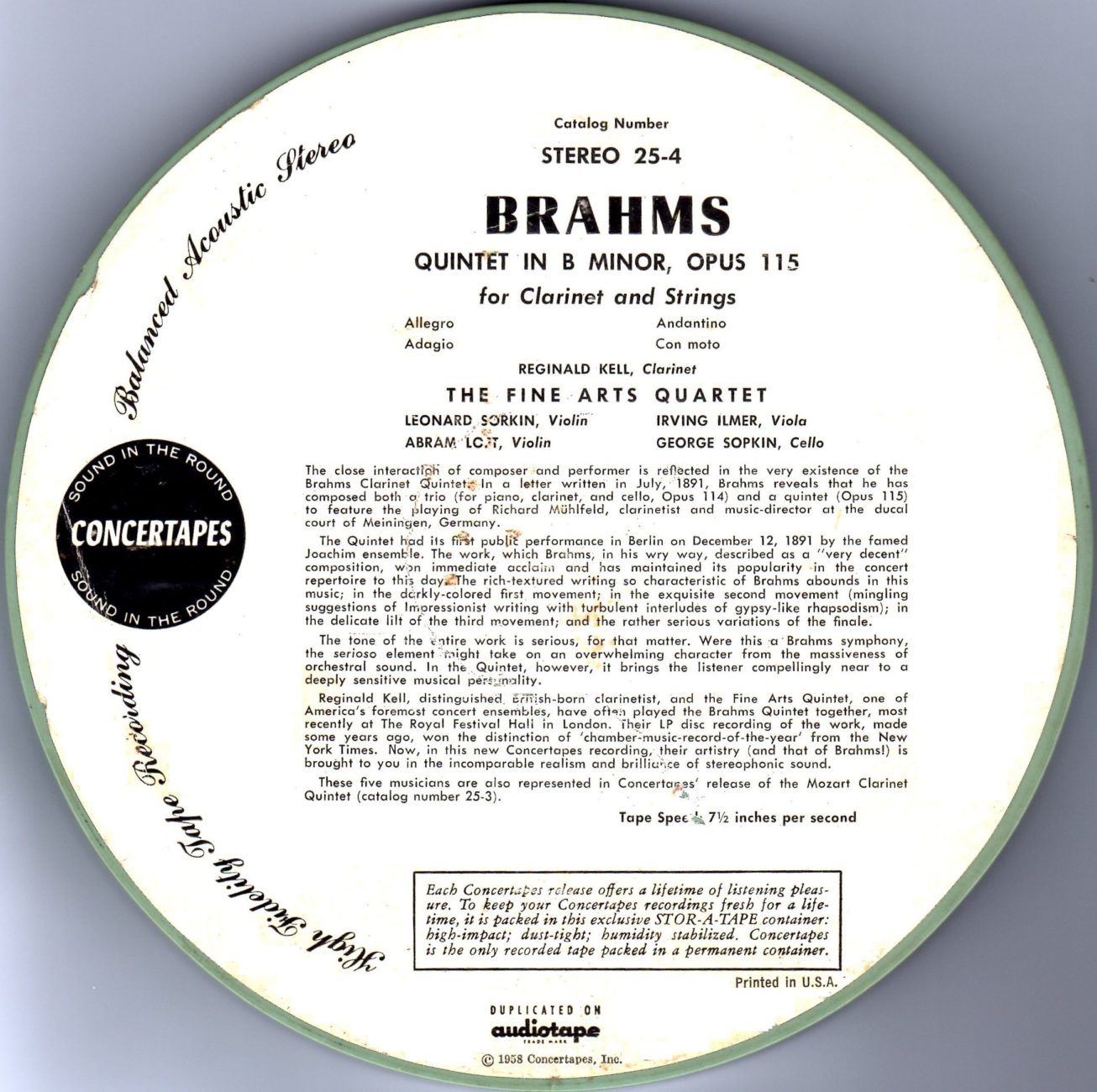

Johannes Brahms Klarinettenquintett Op. 115

Reginald Kell, Clarinet

Fine Arts Quartet (Leonard Sorkin, Abram Loft, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello)

Enregistrement/Recording: 1957

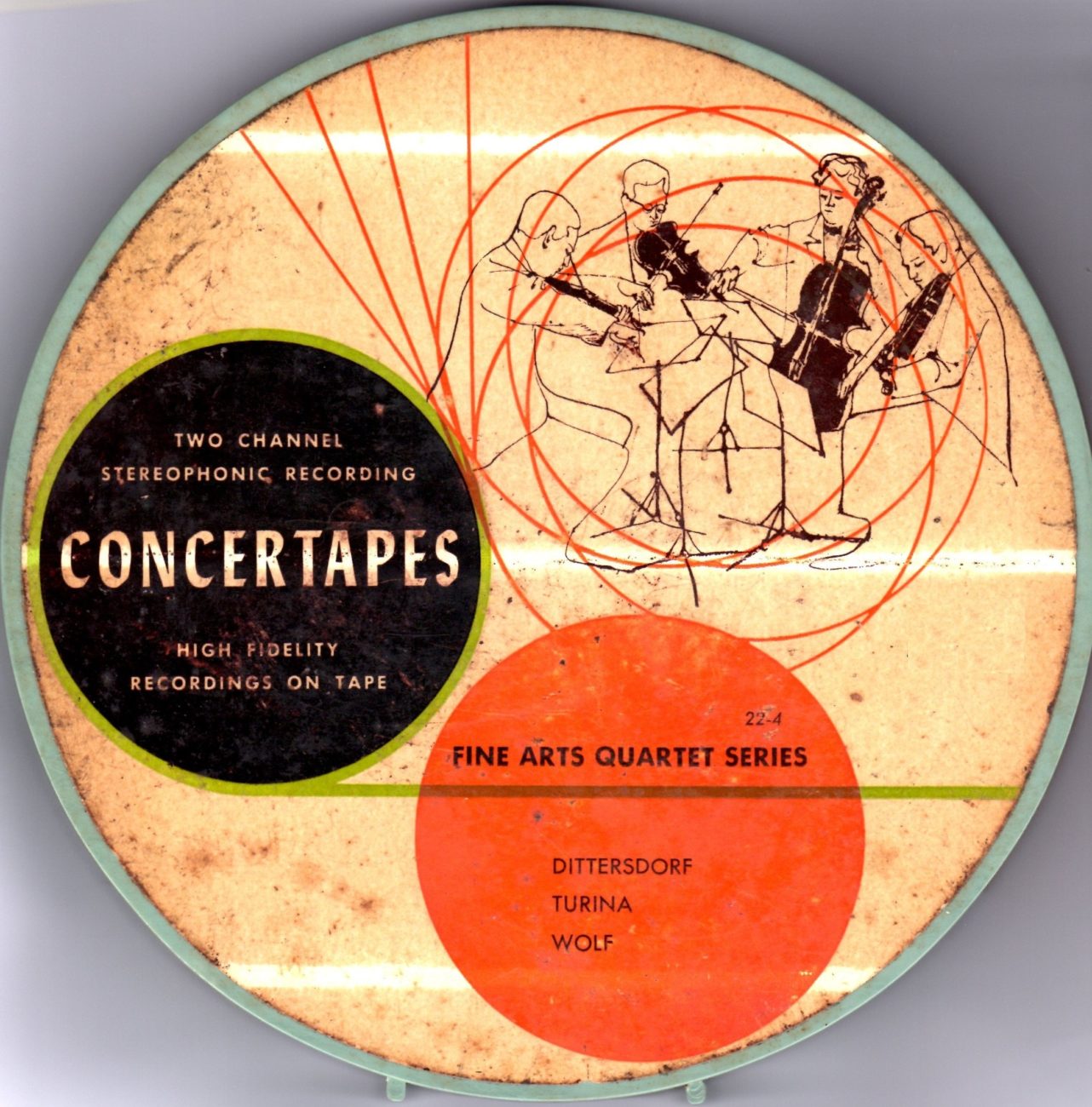

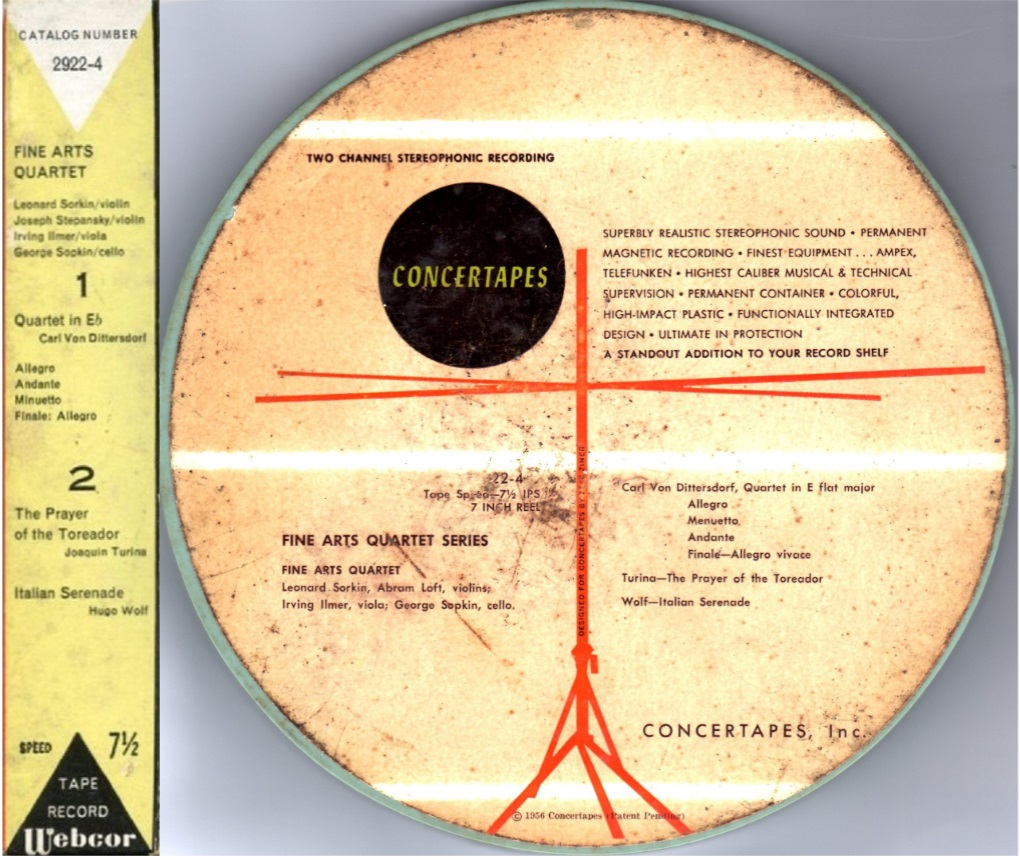

Hugo Wolf Italienische Serenade

Fine Arts Quartet (Leonard Sorkin, Joseph Stepansky, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello)

Enregistrement/Recording: 1953/1954

Source: Bande/Tape – 2 pistes 19cm/s / 2tracks 7.5 ips STEREO

Concertapes 25-4 (Brahms) & 22-4 (Wolf)

Cet enregistrement du Quintette de Brahms Op.115 n’a pas été réédité depuis 1995, et celui de la Sérénade de Wolf ne l’a pas été depuis sa première parution dans les années cinquante. Ce sont donc des raretés discographiques.

Le Fine Arts Quartet a été fondé en 1940 par quatre musiciens du Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), à savoir Leonard Sorkin (1916-1985), Bernard Senescu (1904-1968), Sheppard Lehnhoff (1905-1978) et George Sopkin (1914-2008). En raison de la guerre et de la conscription, le quatuor n’a pu commencer à donner régulièrement des concerts qu’à partir de 1946, avec un nouveau deuxième violon, Joseph Stepansky (1916-1984). En 1952, l’altiste Sheppard Lehnhoff a quitté le quatuor pour réintégrer le CSO et a été remplacé par Irving Ilmer (1919-1997) qui à son tour a été remplacé en 1963 par Gerald Stanick, puis en 1968 par Bernard Zaslav. En 1954, Joseph Stepansky a été remplacé par Abram Loft (1922-2019). Il n’y aura plus de changement jusqu’en 1979 avec le départ d’Abram Loft et de George Sopkin. Leonard Sorkin a quitté le quatuor en 1982 pour être remplacé par Ralph Evans, qui en est toujours le premier violon.

De 1946 à 1954, le Fine Arts Quartet a participé à des émissions radiophoniques hebdomadaires le dimanche matin pour l’ ‘American Broadcasting Company’ (ABC) de Chicago. ainsi qu’à des émissions éducatives télévisées. Il était également un pionnier de l’enregistrement stéréo. Avec le label Webcor (Webster Chicago Corporation), à l’origine un fabricant de magnétophones, puis Concertapes, le label qui a été fondé par le Fine Arts Quartet et lui appartenait, ce qui était rare à l’époque, le Quatuor a réalisé tous ses enregistrements en stéréo à partir de 1953 (notamment Dvorak Op.96 ‘Américain’ et Debussy), avec en 1958 une Intégrale très remarquée des quatuors de Bartók. Un certain nombre de ces enregistrements ont été réédités en 2016 (téléchargement HD), mais ni le Quintette de Brahms, ni la Sérénade d’Hugo Wolf. n’en faisaient partie, alors qu’on y trouvait le Quintette K.581 de Mozart, que Kell a également enregistré en 1957 avec le Fine Arts Quartet, ce qui laisse supposer que la bande originale du Brahms était en mauvais état au point de n’avoir pas pu être copiée. Les Quintettes de Mozart et de Brahms de 1957 ont été les tous derniers enregistrements de Kell, après quoi, il est retourné en Grande-Bretagne en janvier 1958.

Reginald Kell (1906-1981) a enregistré trois fois le Quintette Op.115 de Brahms: le 10 Octobre 1937, avec le Busch Quartet (Abbey Road – Studio n°3), une version mono avec le ‘Fine Arts Quartet of the American Broadcasting Company’ pour American Decca (New York – 2 au 5 Octobre 1951), réédité par DGG dans le coffret de 6CD ‘Reginald Kell the complete ‘American Decca’ recordings’ (00289 477 5280), et enfin, en 1957, le présent enregistrement stéréophonique pour Concertapes, publié sur bandes et en microsillon. Sa dernière publication en microsillon date de 1978 (Concert Hall SMS 2530), et il n’y eut qu’une seule édition en CD, en 1995 (Boston Skyline SD 135), ‘à partir de copies de première génération des bandes originales, conservées par M. Sopkin’.

Dans le numéro du printemps 1999 de l’International Classical Record Collector (ICRC), dans un article sur Reginald Kell, Norman C. Nelson a écrit à propos de cet enregistrement : ‘Le Quintette de Brahms avec les Fine Arts présente l’inconvénient apparemment insurmontable d’être précédé par la version incandescente avec le Quatuor Busch. Ce qui est surprenant, après la formidable impression laissée par l’enregistrement précédent, c’est l’excellence de l’interprétation des Fine Arts, qui présente un jeu plus actif et plus vivant que pour le Quintette de Mozart. L’intensité n’est cependant pas aussi soutenue que dans l’enregistrement avec les Busch, qui tient l’auditeur à la gorge de la première à la dernière note. Le rubato appliqué par Kell dans les premiers passages de clarinette du Quintette est similaire dans les deux enregistrements, bien qu’une vingtaine d’années les séparent. Les deux interprétations avec le Fine Arts restent de belles interprétations dans lesquelles Kell démontre sa maîtrise de l’instrument et son talent artistique unique à la fin de sa carrière d’enregistrement. Seule une légère diminution de la concentration de son timbre est perceptible. Le son du dernier enregistrement est nettement supérieur à celui des deux premiers, en particulier le Brahms de 1937, et certains pourraient même préférer le jeu des cordes plus moderne des Fine Arts au style plus ancien des Busch, qui comprend de nombreux cas de « portamento ».

La Sérénade de Wolf fait partie des quelques enregistrements réalisés par Webcor en 1953 ou 1954, avant que Joseph Stepansky ne soit remplacé par Abram Loft. Webcor l’a publié sur une bande mono (2922-4). La bande stéréo (22-4), publiée en 1956 par Concertapes, mentionne de manière erronée Abram Loft en tant que deuxième violon.

Reginald Kell

The 1957 recording of the Brahms Quintet Op.115 has not been reissued since 1995, and that of the Wolf’s Serenade has not been reissued at all since its first release in the 1950s. They are therefore discographic rarities.

The Fine Arts Quartet was founded in 1940 by four musicians from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO): Leonard Sorkin (1916-1985), Bernard Senescu (1904-1968), Sheppard Lehnhoff (1905-1978) and George Sopkin (1914-2008) . Because of the war and conscription, the quartet was unable to begin giving regular concerts until 1946, but with a new second violinist, Joseph Stepansky (1916-1984). In 1952, violist Sheppard Lehnhoff left the quartet to rejoin the CSO and was replaced by Irving Ilmer (1919-1997), who in turn was replaced in 1963 by Gerald Stanick, then in 1968 by Bernard Zaslav. In 1954, Joseph Stepansky was replaced by Abram Loft (1922-2019). There were no further changes until 1979 with the departure of Abram Loft and George Sopkin. Leonard Sorkin left the quartet in 1982 to be replaced by Ralph Evans, who is still first violin.

From 1946 to 1954, the Fine Arts Quartet took part in weekly Sunday morning radio broadcasts for Chicago’s American Broadcasting Company (ABC), as well as educational television programmes. He was also a pioneer of stereo recording. With the Webcor label (Webster Chicago Corporation), originally a manufacturer of tape recorders, and later Concertapes, the label which was founded by and belonged to the Fine Arts Quartet, which was quite rare then, the Quartet made all his recordings in stereo from 1953 onwards (notably Dvorak Op.96 ‘Américain’ and Debussy), with a highly acclaimed complete recording of Bartók’s quartets in 1958. A number of these recordings were re-issued in 2016 (‘Hi-Res’ download), but neither the Brahms Quintet nor the Hugo Wolf’s Serenade were included, although they did include Mozart’s Quintet K.581, which Kell also recorded in 1957 with the Fine Arts Quartet, which probably means that the master tape of the Brahms was in poor condition to the point of being unplayable. The 1957 Mozart and Brahms Quintets were Kell’s last recordings, after which he returned to Britain in January 1958.

Reginald Kell (1906-1981) made three recordings of Brahms’s Quintet Op.115: on 10 October 1937, with the Busch Quartet (Abbey Road – Studio No. 3), a mono version with the ‘Fine Arts Quartet of the American Broadcasting Company’ for American Decca (New York – 2 to 5 October 1951), reissued by DGG in the 6CD box set ‘Reginald Kell the complete ‘American Decca’ recordings‘ (00289 477 5280), and finally, in 1957, the present stereophonic recording for Concertapes, issued on tape and LP. It was last released on LP in 1978 (Concert Hall SMS 2530), and there has only been one CD release, in 1995 (Boston Skyline SD 135), ‘from first-generation studio masters, preserved by Mr Sopkin’.

In the Spring 1999 Issue of International Classical Record Collector (ICRC), in an article on Reginald Kell, Norman C. Nelson wrote about this recording: ‘The Brahms Quintet with the Fine Arts is at the apparently unsuperable disadvantage of being preceded by the incandescent version with the Busch Quartet. What is surprising, after the terrific impression made by the earlier recording, is the excellence of the Fine Arts performance, which features more urgent, vivid playing than their Mozart Quintet. The intensity, however, is not as sustained as in the Busch recording, which has the listener by the throat from first note to last. The rubato applied by Kell in the opening clarinet passages of the Quintet is similar in both recordings though some 20 years separated them. Both performances with the Fine Arts remain lovely ones in which Kell demonstrates his continuing grip on the instrument and unique artistry at the close of his recording career. Only a slight diminution in the focus of his tone is noticeable. The sound on the last recording is clearly superior to their early counterparts, especially the 1937 Brahms, and some may even prefer the more modern string playing of the Fine Arts to the older style of the Buschs, which includes numerous instances of portamento’.

Wolf’s Serenade is one of the few recordings made by Webcor in 1953 or 1954, before Joseph Stepansky was replaced by Abram Loft. Webcor released it on a mono tape (2922-4). The stereo tape (22-4), published in 1956 by Concertapes, incorrectly lists Abram Loft as second violin.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

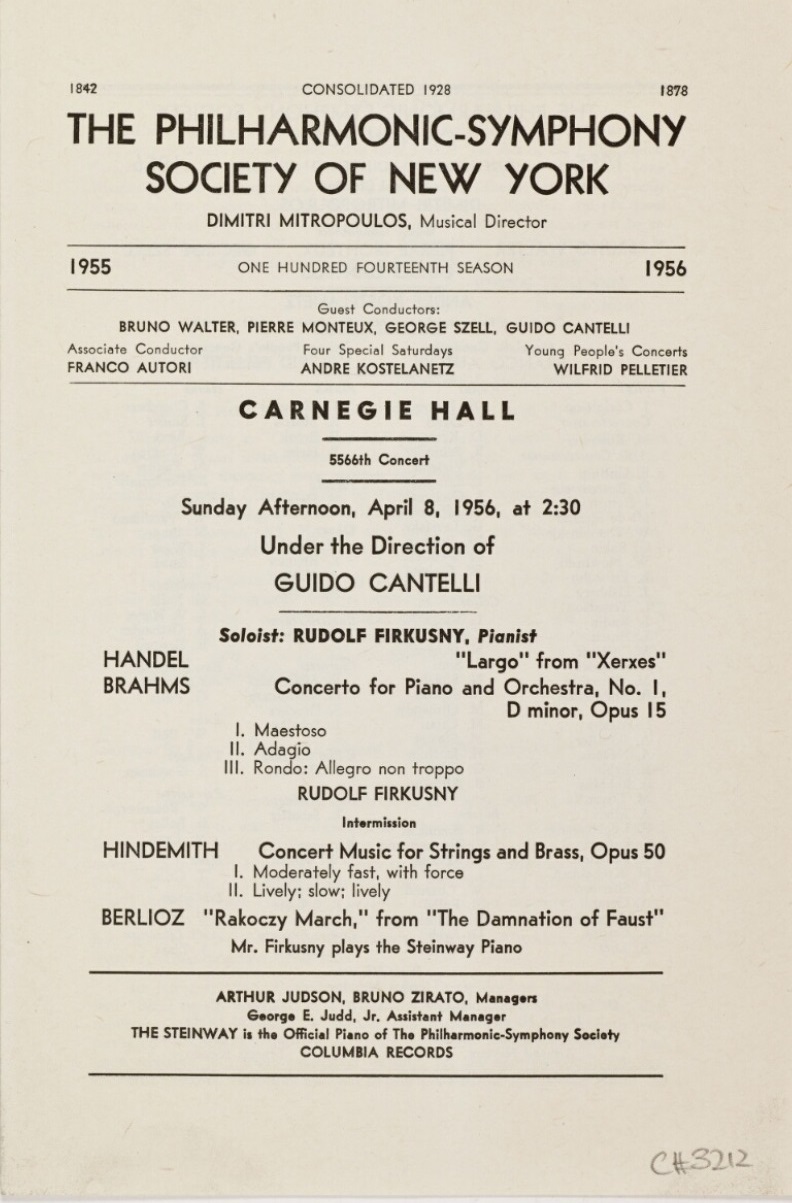

Rudolf Firkušný, piano (Steinway) – Guido Cantelli – New York Philharmonic (NYPO)

Carnegie Hall – April 8, 1956

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Cette très belle interprétation du Premier Concerto de Brahms provient du dernier concert de Guido Cantelli à New-York.

Le pianiste avait beaucoup d’affinités avec le chef, ainsi qu’il l’a relaté dans une interview:

‘Cantelli était toujours extrêmement bien préparé et dirigeait la plupart des œuvres du répertoire de mémoire. J’ai eu énormément de plaisir à travailler avec lui, car nous avons ressenti une certaine affinité dans nos idées musicales. De plus, sa préparation scrupuleuse de l’orchestre rendait la coopération tout à fait idéale. Les concerts ne pouvaient que bien se passer après sa préparation minutieuse lors des répétitions. Bien qu’il soit exigeant et jeune, il était très respecté par les membres de l’orchestre et, je pense, très apprécié en tant que personne. J’ai été étonné par son évolution régulière et son processus de maturation. Notre dernière prestation a montré que son attitude à l’égard de l’orchestre s’était quelque peu adoucie, sans pour autant faire de concessions sur le plan des exigences’.

Les propos de Firkušný se reflètent bien dans des critiques de cette interprétation parues à l’époque:

Louis Biancolli (World Telegram and Sun) : ‘Avec Guido Cantelli dirigeant l’un de ses meilleurs accompagnements à ce jour, l’interprétation a été passionnante, depuis la force tragique et sinistre des accords d’ouverture jusqu’à la dernière explosion jubilatoire du Finale. M. Firkušný était dans une veine exaltante. Il a apporté une vigueur saisissante aux passages héroïques, donnant à la ligne soliste l’avantage d’un son fort et solide qui n’a jamais perdu de sa résonance. Dans les moments calmes également, il s’est montré un véritable poète, mêlant sonorités douces et sentiments tendres, inscrivant des phrases plutôt que des vers et laissant le plaisir de lire – et de penser – librement entre les lignes……. Depuis dix-huit ans que j’entends M. Firkušný jouer, je l’ai vu devenir l’une des personnalités les plus marquantes du clavier. Cette personnalité n’a jamais été aussi imposante qu’hier soir. Par leur tempérament et leur style, le concerto et M. Firkušný semblent avoir été conçus l’un pour l’autre, tant l’unité de la vision poétique est étroite.’

Howard Taubman (New York Times) : Rudolf Firkušný a donné un coup de fouet au concert philharmonique donné hier soir au Carnegie Hall avec une interprétation passionnante du Concerto en ré mineur de Brahms. Pianiste de tempérament, il a apporté poésie et tension dramatique à une œuvre qui exige un mélange de tendresse et de passion.

Il est aujourd’hui un pianiste majeur, l’un des meilleurs de la profession. Son interprétation de Brahms hier soir en est une nouvelle preuve. Il l’a fait dans la grande tradition. Dans le premier mouvement, qui est un drame puissant en soi, M. Firkušný a joué avec une profondeur et une solidité de ton, avec une compréhension de l’idiome romantique particulier de Brahms et avec une vitalité qui a parcouru toute son interprétation. Et même, à un moment donné, une série d’accords fortissimo était d’une intensité presque choquante. Mais le charme n’a pas été rompu : c’est comme si le pianiste secouait l’orchestre et le public pour les amener à un rapport plus concentré.

Guido Cantelli, qui entamait sa dernière semaine en tant que chef invité, a bénéficié d’un bien meilleur accompagnement de la part de l’orchestre que lorsqu’il avait fait appel cette saison, à deux reprises, à des pianistes solistes. Le mouvement lent, avec son chant soutenu et méditatif, était particulièrement envoûtant, et M. Firkušný s’y est montré un poète sensible, jouant avec une grande richesse de nuances.

This beautiful performance of Brahms’ First Piano Concerto comes from Guido Cantelli’s last concert in New York.

The pianist had a great affinity with the conductor, as he recounted in an interview:

‘Cantelli was always extremely well prepared, conducting most of the standard repertoire from memory. I enjoyed working with him enormously as we felt a certain affinity in our musical ideas. Also, his scrupulous preparation of the orchestra made the cooperation quite ideal. The performances had to go well after his careful preparation in rehearsals. Although he was demanding and young, he was greatly respected by the orchestra members and I think very much liked as a person. I was amazed by his steady growth and maturing process. Our last performance showed that his attitude towards the orchestra had mellowed somewhat, yet without any concessions in his demands’.

Firkušný’s words are well reflected in reviews of this interpretation published at the time:

Louis Biancolli (World Telegram and Sun): ‘With Guido Cantelli conducting one of his finest accompaniments to date, the performance was a stirring one from the grim tragic strength of the opening chords to the jubilant last flourish of the Finale. Mr. Firkušný was in exalted vein. He brought arresting vigour to the heroic passages, giving the solo line the benefit of a strong, solid tone that never lost resonance. Also in the quiet places he was the true poet, mixing soft-spun sound with tender feeling, inscribing phrases instead of verses and allowing one the pleasure of reading – and thinking – freely between the lines…… In the eighteen years I have heard Mr. Firkušný play, I have watched il grow into one of the most commanding personalities of the keyboard. That personality was never so commanding as it was last night. In temperament and style, the Concerto and Mr. Firkušný seemed to have been intended for one another, so close was the unity of poetic vision.

Howard Taubman (New York Times): ‘Rudolf Firkušný gave a lift to the last night’s Philharmonic concert given at Carnegie Hall with an exciting performance of Brahms’ D minor Concerto. He is a pianist of temperament, and he brought poetry and dramatic tension to a work that demands a commingling of tenderness and passion.

He is now a major pianist, one of the best in the profession. His performance of Brahms last night was further evidence of this. It was in the grand manner. In the first movement, which is a powerful drama in itself, Mr. Firkušný played with depth and solidity of tone, with a grasp of Brahms’ special romantic idiom and with a vitality that pulsed through his entire interpretation. Indeed, at one point, a series of fortissimo chords was almost schocking in its intensity. But, the spell was not brocken: it is as if the pianist were jolting orchestra and audience into more concentrated rapport.

Guido Cantelli, who began his final week as guest conductor, got a much better accompaniment from the orchestra than he had on two previous occasions this season when he had piano soloists. The slow movement, with its sustained, meditative song was especially enamoring, and here Mr. Firkusny was the sensitive poet, playing with a wealth of nuance.’

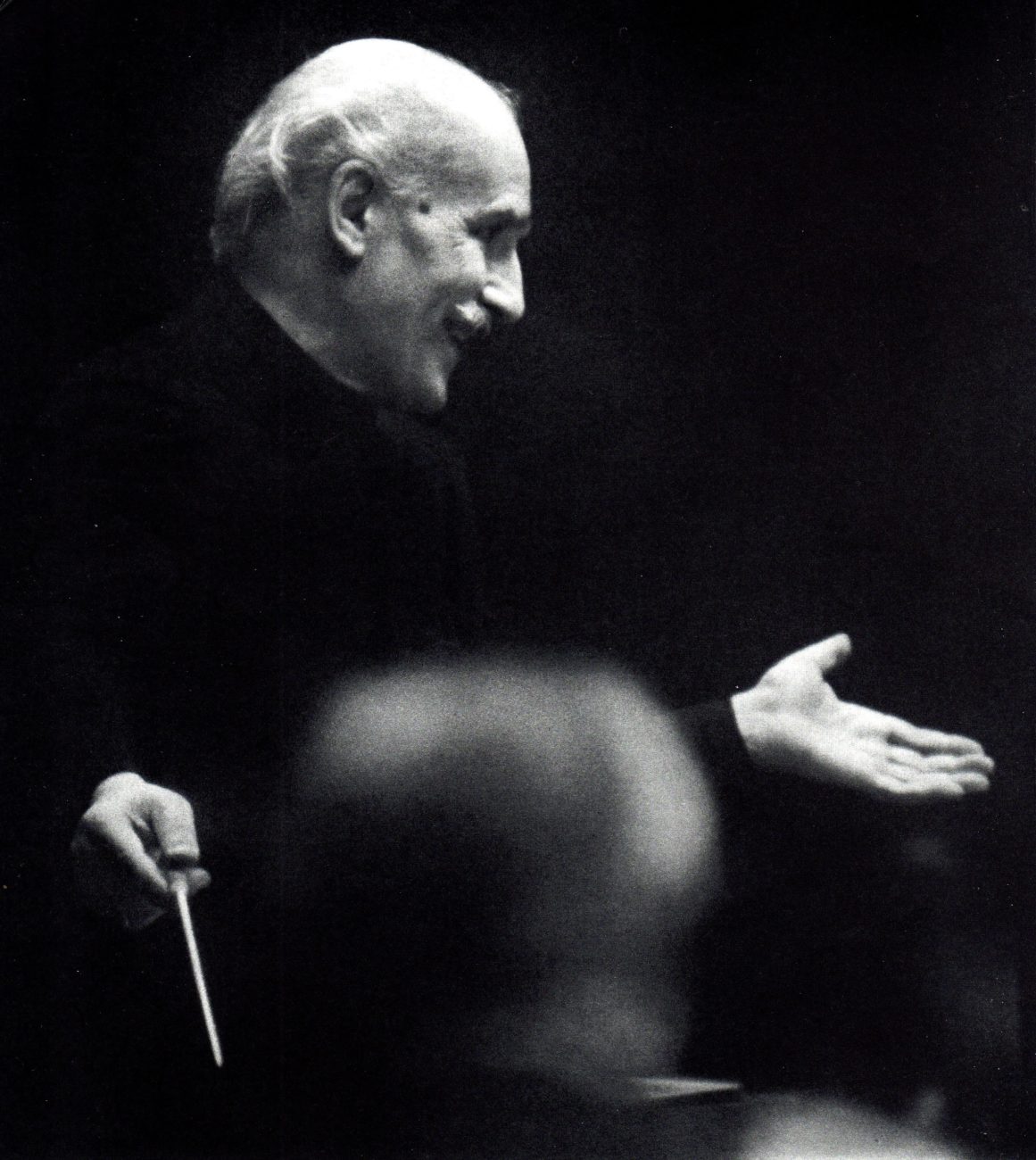

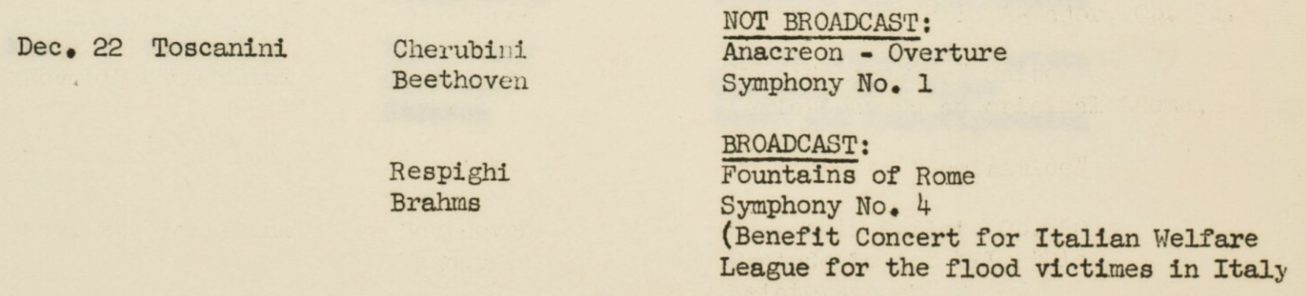

Arturo Toscanini NBC SO

Brahms Symphony n°4 Op.98

Carnegie Hall – December 22, 1951

Prod: Don Gillis – Eng: George Mathes

Source: Bande / Tape – 38 cm/s / 15 ips

La ‘Quatrième’ de Brahms a toujours réussi à Arturo Toscanini, comme le prouvent les nombreux enregistrements dont on dispose entre les concerts des 3 & 5 mai 1935 au Queen’s Hall de Londres avec le BBC SO et celui du 1er Octobre 1952 au Royal Festival Hall de Londres avec le Philharmonia Orchestra.

Entre temps, nous avons pas moins de six interprétations captées en concert avec le NBC SO (11 février 1939, 10 Janvier 1943, 28 Octobre 1945, 27 Novembre 1948, 26 février 1950 et enfin 22 Décembre 1951 lors d’un concert au profit de l’ ‘Italian Welfare League’), mais aussi un enregistrement fait à Carnegie Hall pour RCA le 3 Décembre 1951*, c’est-à-dire la version ‘officielle’ que connaissent les mélomanes.

Si la préférence des critiques va au concert de 1948 (réédité dans l’Album de 2CD EMI ‘Great Conductors of the 20th Century’ Ref: 7243 5 62939 2 2), il n’en est pas moins vrai que la version inédite du 22 décembre 1951 possède des vertus propres tout à fait convaincantes.

En effet, elle surclasse nettement la version en studio réalisée trois semaines auparavant.

Comme c’est souvent le cas avec Toscanini, l’enregistrement de concert s’avère beaucoup plus libre dans les phrasés avec ici de très beaux passages cantabile, dans la rythmique qui respire plus, ainsi que dans la conduite du discours musical, plus variée. L’inspiration est au rendez-vous!

D’autre part, la prise de son en public à Carnegie Hall (due à George Mathes) est d’un naturel tout à fait remarquable.

*En fait, cette symphonie a été jouée six fois au cours de la tournée de 1950 du NBC SO (14 avril-27 mai), et Toscanini voulait qu’elle fasse partie des enregistrements réalisés début juin, mais ce projet a été annulé au profit de l ‘Ibéria’ de Debussy.

The Brahms ‘Fourth’ has always been a success for Arturo Toscanini, as evidenced by the many recordings available between the concerts of 3 & 5 May 1935 at Queen’s Hall in London with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the concert of 1 October 1952 at the Royal Festival Hall in London with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

In between, we have no less than six performances recorded in concert with the NBC SO (11 February 1939, 10 January 1943, 28 October 1945, 27 November 1948, 26 February 1950 and finally 22 December 1951 at a concert in aid of the Italian Welfare League) but also a recording made at Carnegie Hall for RCA on 3 December 1951*, i.e. the ‘official’ version known to music lovers.

Although critics rather prefer the 1948 concert (reissued in the EMI 2CD album ‘Great Conductors of the 20th Century’ Ref: 7243 5 62939 2 2), it is nevertheless true that the previously unpublished version of 22 December 1951 has its own convincing virtues.

Indeed, it clearly outperforms the studio version made three weeks earlier.

As is often the case with Toscanini, the concert recording proves to be much freer in the phrasings, here with some very beautiful cantabile passages, in the rhythmic pattern, which breathes more, and in the conduct of the musical discourse, which is more varied. The inspiration is here!

On the other hand, the live recording at Carnegie Hall (by George Mathes) is remarkably natural.

*In fact, this symphony was played six times during the NBC SO 1950 tour (14 April-27 May), and Toscanini wanted it to be included in the recordings made in early June, but this project was cancelled in favour of Debussy’s ‘Ibéria’.

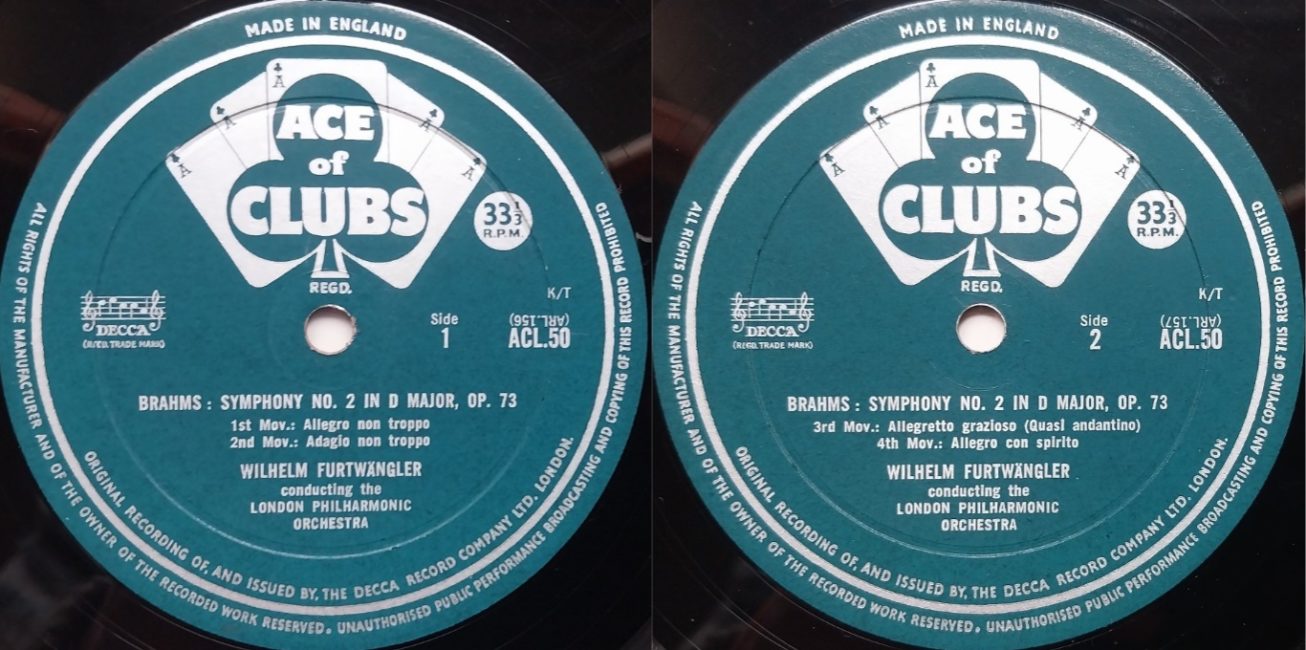

Kingsway Hall – 20,22,24 & 25 March 1948 Prod: Victor Olof – Eng: Kenneth Wilkinson

Source: 33t/LP Decca ACL 50 (1959)*

Entre le 29 février et le 25 mars 1948, Furtwängler a donné une série de dix concerts avec le LPO dont six à Londres et quatre en tournée, avec notamment au programme les quatre symphonies de Brahms (la Deuxième a été jouée à Londres le 11 mars), le dernier concert, le 25 mars,ayant été consacré à la Neuvième de Beethoven. Quatre jours d’enregistrement ont été consacrés à cette Deuxième (20,22,24 et 25 mars), et le 26 mars, Furtwängler a enregistré pour EMI l’Immolation de Brünnhilde avec Kirsten Flagstad et le Philharmonia, avant de partir pour une série de concerts à Buenos Aires.

La reproduction du son de cet enregistrement de la Deuxième de Brahms a toujours été problématique, et ce pour plusieurs raisons. John Culshaw raconte dans son livre ‘Putting the Record Straight’ que Furtwängler aurait refusé l’utilisation de plusieurs microphones, si bien que la captation a eu lieu avec un seul microphone, ce qui était cependant une pratique relativement courante à l’époque. Par exemple, DGG a enregistré de cette façon à la Jesus Christ Kirche de Berlin en 1953 la Symphonie n°4 de Schumann avec Furtwängler et le BPO. Toutefois Decca n’utilisait pas cette méthode et il se peut que cela ait créé des difficultés, car la prise de son par Decca de cette symphonie de Brahms manque peut-être un peu de présence, quoique, lors de la sortie des 78tours, EMG Letter a loué la chaleur du son dans l’excellente acoustique de Kingsway Hall. A ceci s’ajoute le problème lié à la définition de la courbe de gravure FFRR utilisée par Decca pour les microsillons (le disque LXT 2586 est paru en juin 1951), car l’éditeur en a utilisé plusieurs versions au début des années cinquante sans que les disques renseignent l’exacte version mise en œuvre.

La réédition de 1959 dans la collection ‘Ace of Clubs’ (ACL 50) permet de lire ce microsillon avec la bonne courbe FFRR, et de restituer la prise de son avec son équilibre tonal d’origine. On notera que lire ce disque avec la courbe RIAA qui est devenu un standard depuis les années 80, donne un son déséquilibré, et on perd beaucoup de l’interprétation, notamment avec un manque de graves qui affecte beaucoup la dynamique.

La prise de son est très musicale, et reproduit l’ambiance de salle du Kingsway Hall. On perçoit bien le son caractéristique de Furtwängler, ainsi que le fait que l’orchestre n’a pas la profondeur de son du BPO ou du WPO, ce qui n’est pas forcément un inconvénient pour cette œuvre.

Kingsway Hall

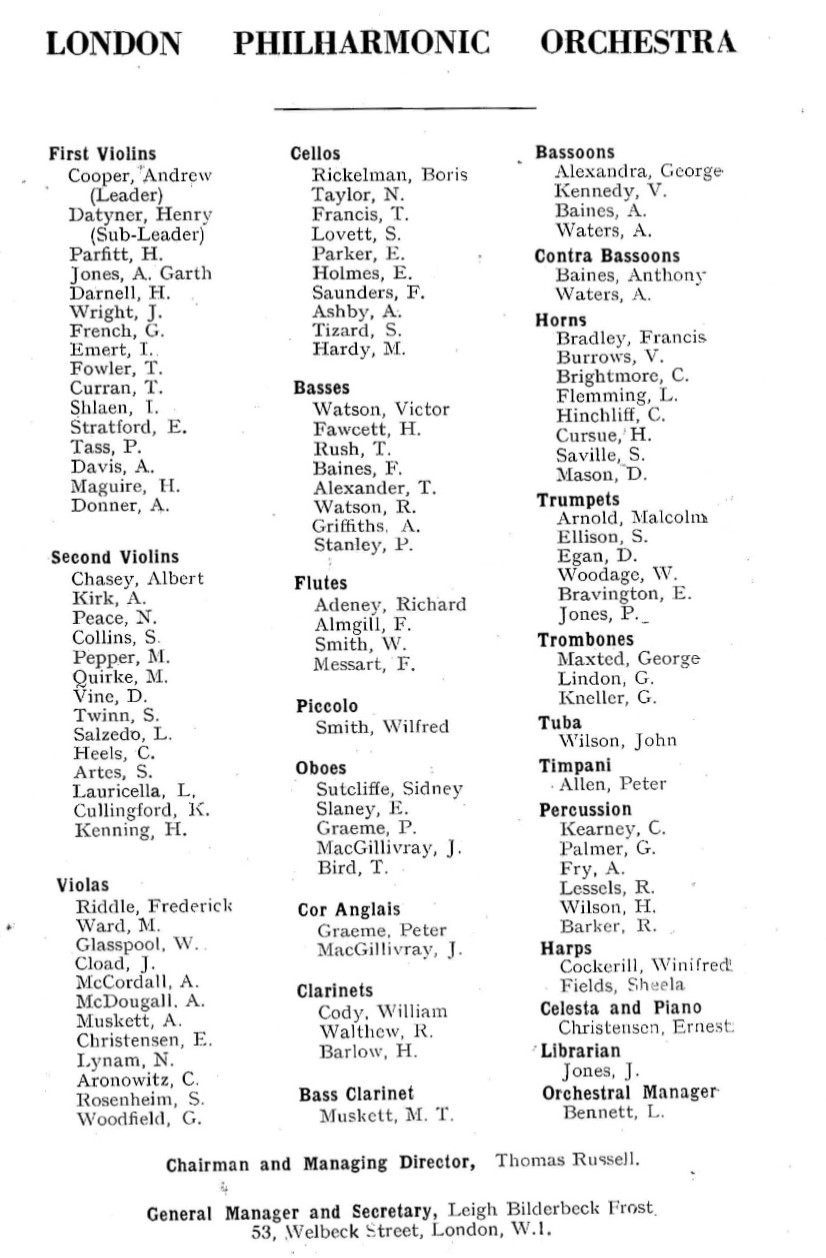

LPO Members – 1948

Between February 29 and March 25 1948, Furtwängler gave a series of ten concerts with the LPO, six in London and four on tour, with among others Brahms’ four symphonies on the program (the Second was played in London on March 11), and the last concert, on March 25, was devoted to Beethoven’s Ninth. Four days of recording were devoted to this Second symphony (March 20, 22, 24 and 25), and on March 26, Furtwängler recorded for EMI Brünnhilde’s Immolation with Kirsten Flagstad and the Philharmonia, before leaving for a series of concerts in Buenos Aires.

The reproduction of the sound of this recording of Brahms’ Second has always been problematic, for several reasons. John Culshaw tells us in his book ‘Putting the Record Straight’ that Furtwängler refused to use several microphones, so the recording was made with only one microphone, which was however a relatively common practice at the time. For example, DGG recorded Schumann’s Symphony no. 4 with Furtwängler and the BPO at the Jesus Christ Kirche in Berlin in 1953. However, Decca did not use this method and this may have created difficulties, as Decca’s recording of this Brahms symphony perhaps lacks a bit of presence, although when the 78s were released, EMG Letter praised the warmth of the sound in the excellent acoustic of Kingsway Hall. Added to this is the problem of the definition of the FFRR curve used by Decca for the LPs (LXT 2586 was released in June 1951), as the publisher used several versions of it in the early 1950s without the discs providing information on the exact version used.

The 1959 reissue in the ‘Ace of Clubs’ collection (ACL 50) allows to play this LP with the correct FFRR curve, to restore the recording with its original tonal balance. It should be noted that playing this record with the RIAA curve, which has become a standard since the 80’s, gives an unbalanced sound, and we lose a lot of the interpretation, especially with a lack of bass which severely affects the dynamics.

The sound recording is very musical, and reproduces the atmosphere of the Kingsway Hall. One can hear Furtwängler’s characteristic sound, as well as the fact that the orchestra does not have the depth of sound of the BPO or the WPO, which is not necessarily a drawback for this work.