Étiquette : Puccini

27, 28, 30 August & 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30 September 1942

17, 21, 23, 25, 31 July 1943

A tribute to mark the centenary of her birth

Version Française: cliquer ICI

Maria Callas sang the role of Floria Tosca throughout her stage career, from 1942 to 1965. At the Greek National Opera, which was founded in 1939, she was able to benefit from exceptional working conditions to present this work in a new production when she was only 18, at a time when Greece was undergoing extremely harsh occupation conditions. Nicholas Petsalis-Diomidis’s indispensable book ‘The Unknown Callas – The Greek Years’ describes in detail how this new presentation of Tosca was staged, how Callas’s acting and singing fascinated from the outset, and how the production became a kind of benchmark for herself and for many other directors, so that twenty years later, and even more, it continued to influence new productions.

In a 1978 interview, actress Edwige Feuillère declared: ‘I admired Maria Callas at the Paris Opera in Tosca. She was extraordinarily beautiful and musical, but above all, for me as an actress, she was doing something extraordinary. I was at the Opera’s basket, and in the second act, where she is with Scarpia, I saw the precise moment when the idea of murder was germinating in her mind: you could see her eye stop on the knife on the table, the glass she was holding to her lips stop mid-stroke, and from a distance, you knew that this woman was going to kill Scarpia. It’s a marvellous piece of interpretative work, and it touched me deeply. For me, there was magic in it. Her vibrations were magical, there was a kind of exoticism in her timbre. All the beauty in her person was acquired beauty and elegance, and on top of that, there was all the incessant work on incomparable gifts, and the sum of all that is genius. This is a woman who, during her short trajectory, thought of nothing but recreating herself every day at every moment.‘

As Edwige Feuillère has pointed out, making the most of genius requires ceaseless work, and what is at first sight fascinating about Callas is that by 1942, she had already defined the exacting working methods that enabled her to do so, and which she would apply throughout her career. What’s even more fascinating is that, at such a young age, she was able to build a memorable interpretation of the character.

She had begun studying Tosca in 1938 with her teacher at the time, Maria Trivella, associate professor at the Athens Conservatory. At the instigation of tenor Ulysses Lappas, and after a favorable opinion from Elvira de Hidalgo, Maria Kalogeropoulou was officially chosen by the General Secretary of the National Theater Angelos Terzakis on July 10, 1942 to sing the role of Floria Tosca in a series of eighteen performances of Tosca under the direction of conductor Sotos Vassiliadis with stage director Dino Yannopoulos. The performances which were sold out, took place between August 27 and September 30, 1942, at the open-air Summer Theater in Athens’ Klafthmonos Square, a small venue with a modestly sized stage, with a premiere on August 27 for the version sung in Greek in Angelos Terzakis‘s translation, and on September 8 for the version sung in Italian (3 performances). Among the main characters, she was the only one to sing in both languages, and therefore had to learn the work and ensure all rehearsals in Greek and Italian. Mario was sung in Greek by Antonis Delendas and in Italian by Loudovikos Kourousopoulos. Baron Scarpia was sung in Greek by Titos Xirellis and Spyros Kalogeras (from September 24), and in Italian by Lakis Vassilakis. A revival with the same cast took place in 1943 for five performances in Greek ( July 17, 21, 23, 25 and 31 ).

Summer Theater at Klafthmonos Square (Athens)

Piano rehearsals for Tosca began in the hall of the National Theatre. According to Loudovikos Kourousopoulos, from the very first rehearsals, Callas was exceptional in her musicality and virtuosity. The two casts rehearsed alternately in Greek and Italian, and she had to be present at all times. When rehearsals with orchestra began at the theater in Klafthmonos Square, she always sang in full voice, without saving herself, as she would continue to do throughout her career. As her short-sightedness prevented her from seeing the conductor, she also attended rehearsals reserved for the orchestra alone, so as not to have to depend on the conductor’s gestures. In addition, Callas also studied the role in private rehearsals with conductor Sotos Vassiliadis and baritone Titos Xirellis, who was a renowned singer and composer. In particular, the latter taught her how to play the difficult scene in Act II between Scarpia and Tosca, which she would benefit from in all subsequent performances throughout her career.

At the premiere on Thursday August 27, 1942, the audience quickly realized that Maria Kalogeropoulou was someone to be noticed. According to Dino Yannopoulos, ‘When she came on stage, it was as if she took the audience by the scruff of the neck and said: Now, hear me!, I’ve something to say’. Antonis Kalaidzakis, a member of the chorus that night, says: ‘I remember that ‘Mario, Mario, Mario!’. It sent a shiver down your spine! It was a cry that came straight from the heart. That voice of hers was strange, there was a natural sob in it that projected you straight into an atmosphere of drama. The sound was a bit throaty, but attractively throaty, like the sound of a string instrument when not played absolutely true. It became crystal clear only on the high notes’.

After the aria ‘Vissi d’arte’ which she had to encore at each performance, the scene where she stabs Scarpia was impressive thanks to the ‘business’ devised by Yannopoulos and brilliantly performed by Maria. As Scarpia sat at his desk writing the safe-conduct Tosca has asked of him, she backed diagonally downstage toward the table. Stefanos Ciotakis, another member of the chorus, recalled: ‘On the table was the dagger, with the hilt toward her. She moved closer and closer to the table, walking rather unsteadily and we, knowing she could’nt see, were on tenterhooks. Would she put her hand on it or..?. But she, having measured her paces to perfection, arrived at the table and picked up the dagger with absolute precison, without even turning her head. That really froze the blood in our veins! ‘

Andonis Kalaidzakis remembers with emotion how, after Scarpia’s stabbing, Maria let the dagger drop from her hand and placed a candle on either side of the dead tyrant. The audience felt a thrill of excitement when Maria extracted the note clutched in the dead Scarpia’s hand. And then, she made her exit with another clever piece of staging by Dino Yannopoulos: walking at stage right, with her ermine cloak thrown over her shoulder and trailing on the floor, Maria turned round to look back at the dead Scarpia, while the curtain was drawn across from stage left to bring the scene to an end. Luschino Visconti acknowledged that he had admired that ingenious touch. Franco Zeffirelli was inspired by it, as was Benoit Jacquot much later (2001) in his film.

Her voice already had its essential properties. For the tenor Loudovikos Kourousoupoulos who was Mario in the three performances sung in Italian , ‘if you heard her sing without seeing her, you would think it was three different people singing. She had difficulties with the transitions from one register to another. When she hit a high note cleanly her voice didn’t wobble, but on an upward portamento it did. However, she had such a big vocal range and such warmth of tone, and above all her acting was so good, that those things were forgotten. The whole effect was so vibrantly alive that it made you jump out of your seat.’ This is confirmed by Nikos Papachristos, who was in the chorus: ‘We were baffled and taken aback by her voice. It had so many different tone colors that it lacked homogeneity: a high voice, a middle voice, and a low voice, all quite distinct. But there was a tremendous fluency throughout, and she acted so naturally on stage that you overlooked her vocal flaws.’

with Loudovikos Kourousopoulos

On Herbert Graf’s recommendation, Dino Yannopoulos was hired as principal director at the MET and remained there between 1946 and 1967. There, Callas met him again for his stage directions of Tosca (in 1956, 1958 and 1965) and of Norma in 1956. The excerpts from the end of Act II filmed during the Ed Sullivan Show on November 25, 1956 (dir: Dimitri Mitropoulos with George London, Scarpia) give us an idea of his staging, with particularly, at the very end, Callas’ famous exit with her cloak trailing on the floor.

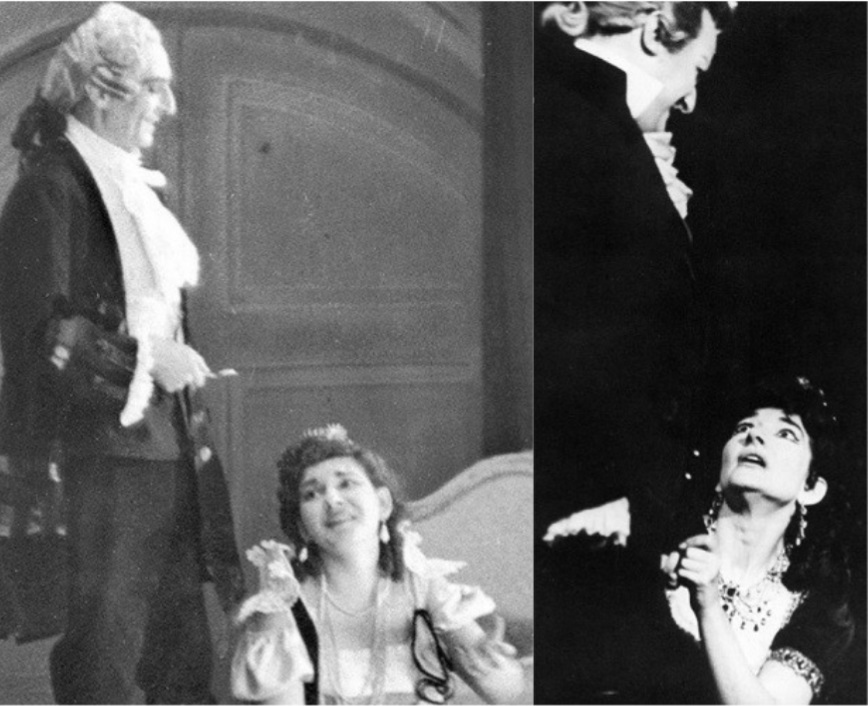

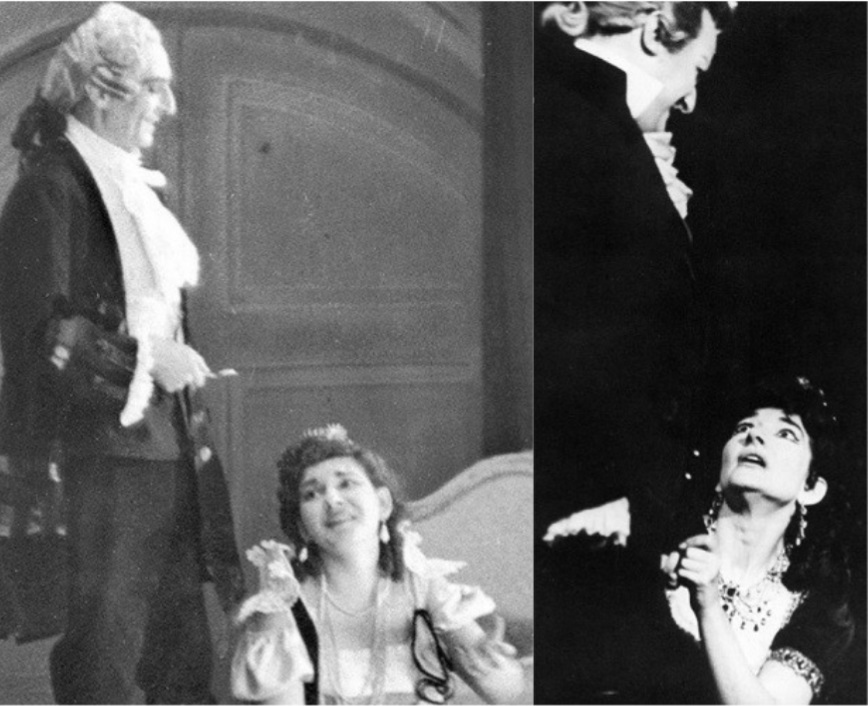

The comparative photographs below, taken on stage during the rehearsals of Act II in 1942 in Athens with stage director Dino Yannopoulos, and in 1964 in London (Covent Garden) under the direction of Franco Zeffirelli, show astonishing visual similarities between the two productions taken at the very beginning (in 1942, she was not yet 19) and near the end of Maria Callas’ stage career. Her very last public performance of an opera was Tosca at Covent Garden on July 5, 1965.

On the pictures below: Left: Athens Opera 1942; Right: London Covent Garden 1964

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

______

Act II Tosca/Mario – Left: with Antonis Delendas ; Right: with Renato Cioni

______

Act II – ‘Vissi d’arte’

______

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

N.B. Some sources claim that Maria Callas sang Tosca in Athens in July 1941 to replace an ailing singer. This information is incorrect. There were no performances of Tosca at the National Theater in 1941. It was only in 1942, with the new production, that Tosca began to be performed there.

27, 28, 30 Août & 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30 Septembre 1942

17, 21, 23, 25, 31 Juillet 1943

Un hommage à l’occasion du centenaire de sa naissance

English Version: click HERE

Maria Callas a chanté le rôle de Floria Tosca pendant toute sa carrière scénique de 1942 à 1965. A l’Opéra National de Grèce, fondé en 1939, elle a pu bénéficier de conditions de travail assez exceptionnelles pour présenter cette œuvre dans une nouvelle production alors qu’elle n’avait que 18 ans, à une époque où la Grèce subissait des conditions d’occupation extrêmement dures. Le livre indispensable de Nicholas Petsalis-Diomidis ‘The Unknown Callas – The Greek Years’ décrit en détail comment cette nouvelle présentation de Tosca a été montée, comment le jeu scénique et le chant de Callas ont fasciné dès le début, mais aussi par quel mécanisme de travail en profondeur cette production est devenue une sorte de référence pour elle-même et pour certains metteurs en scène et non des moindres, à tel point que vingt ans plus tard, voire plus, elle a continué à influencer de nouvelles mises en scène.

Dans une interview de 1978, la comédienne Edwige Feuillère a déclaré: ‘J’ai admiré Maria Callas à l’Opéra de Paris dans Tosca. Elle y était extraordinaire de beauté, de musicalité, mais surtout, pour moi comédienne, elle faisait une chose extraordinaire. J’étais à la corbeille de l’Opéra et au Deuxième Acte où elle est avec Scarpia, j’ai vu le moment précis où dans son esprit germait l’idée du meurtre, c’est-à-dire qu’on voyait son œil s’arrêter sur le couteau qui était sur la table, le verre qu’elle portait à ses lèvres s’arrêtait à mi-course et de très loin, on savait que cette femme allait tuer Scarpia. C’est un merveilleux travail d’interprète et ça m’avait beaucoup touché. Pour moi, il y avait de la magie dans son cas. Ses vibrations étaient des vibrations magiques, il y avait une sorte d’exotisme du timbre. Tout ce qu’il y a eu de beauté dans sa personne, c’étaient la beauté et l’élégance acquises et là-dessus, il y avait tout le travail incessant sur des dons incomparables et l’addition de tout ça, c’est le génie. C’est une femme qui, pendant sa courte trajectoire, n’a pensé qu’à se recréer chaque jour à chaque instant.’

Comme l’a souligné Edwige Feuillère, valoriser le génie nécessite un travail incessant et ce qui est de prime abord fascinant avec Callas, c’est qu’en 1942, elle avait déjà défini les méthodes de travail exigeantes qui lui ont permis de le faire, et qu’elle appliquera tout le long de sa carrière. Ce qui est encore plus fascinant est, qu’aussi jeune, elle ait été en mesure d’incarner de façon mémorable le personnage.

Elle avait commencé à étudier Tosca en 1938 avec son enseignante de l’époque, Maria Trivella , professeur associée au Conservatoire d’Athènes. Sous l’impulsion du ténor Ulysses Lappas, et après un avis favorable d’Elvira de Hidalgo, Maria Kalogeropoulou a été officiellement choisie par le secrétaire général du Théâtre National Angelos Terzakis le 10 juillet 1942 pour chanter le rôle de Floria Tosca dans une série de dix-huit représentations de Tosca sous la direction du chef d’orchestre Sotos Vassiliadis avec comme metteur en scène Dino Yannopoulos. Elles eurent lieu à guichet fermé entre le 27 août et le 30 septembre 1942 au Théâtre d’été en plein air de la place Klafthmonos à Athènes, une petite salle avec une scène de dimensions modestes, avec une Première le 27 août pour la version chantée en grec dans la traduction d’Angelos Terzakis et le 8 septembre pour la version chantée en italien (3 représentations). Parmi les personnages principaux, elle était la seule à chanter dans les deux langues et devait donc apprendre l’œuvre et assurer l’ensemble des répétitions en grec et en italien. Mario était chanté en grec par Antonis Delendas et en italien par Loudovikos Kourousopoulos. Le baron Scarpia était chanté en grec par Titos Xirellis et par Spyros Kalogeras (à partir du 24 septembre) et en italien par Lakis Vassilakis. Une reprise avec la même distribution a eu lieu en 1943 pour cinq représentations en grec (17, 21, 23, 25 et 31 juillet).

Théâtre d’été de la place Klafthmonos (Athènes)

Les répétitions de Tosca ont commencé avec piano dans la salle du Théâtre National. Selon Loudovikos Kourousopoulos, dès les premières répétitions, Callas était exceptionnelle de musicalité et de virtuosité. Les deux distributions répétaient en alternance en grec et en italien et elle devait être toujours présente. Quand les répétitions avec orchestre commencèrent au théâtre de la place Klafthmonos, elle a toujours chanté à pleine voix, sans s’économiser, ce qu’elle continuera à faire pendant toute sa carrière. Comme en raison de sa myopie, elle ne pouvait voir le chef, elle a également assisté aux répétitions réservées à l’orchestre seul pour ne pas avoir à dépendre de la gestique du chef. En plus, Callas a également étudié le rôle dans des répétitions privées avec le chef d’orchestre Sotos Vassiliadis et le baryton Titos Xirellis qui était un chanteur reconnu et également un compositeur. Ce dernier lui a en particulier enseigné comment jouer la difficile scène de l’Acte II entre Scarpia et Tosca, ce dont elle tirera profit pour toutes les représentations postérieures tout au long de sa carrière.

Lors de la première, le jeudi 27 août 1942, le public a vite compris que Maria Kalogeropoulou était quelqu’un de remarquable. Selon Dino Yannopoulos: quand elle est entrée en scène, c’est comme si elle avait pris le public par la peau du cou et lui avait dit : maintenant, écoutez-moi, j’ai quelque chose à vous dire ». Antonis Kalaidzakis, membre du chœur ce soir-là, raconte : « Je me souviens de ce « Mario, Mario, Mario ! », qui vous donnait des frissons ! C’était un cri qui venait directement du cœur. Sa voix était étrange, elle avait un sanglot naturel qui vous projetait directement dans une atmosphère de drame. Le son était un peu guttural, mais joliment guttural, comme le son d’un instrument à cordes lorsqu’il n’est pas joué tout à fait correctement’.

Après l’aria « Vissi d’arte » qu’elle a du bisser à chaque représentation, la scène où elle poignarde Scarpia a impressionné grâce à l’ « opération » imaginée par Yannopoulos et brillamment exécutée par Maria: alors que Scarpia, assis à son bureau, rédigeait le sauf-conduit que Tosca lui avait demandé, elle a reculé en diagonale vers la table, depuis la scène. Stefanos Ciotakis, un autre membre du chœur, se souvient : « Sur la table se trouvait le poignard, la poignée tournée vers elle. Elle s’est rapprochée de plus en plus de la table, en marchant de manière plutôt instable, et nous, sachant qu’elle ne pouvait pas voir, étions sur les dents. Allait-elle mettre la main dessus ou… ? Mais, ayant mesuré ses pas à la perfection, elle est arrivée à la table et a pris la dague avec une précision absolue, sans même tourner la tête. Voilà qui nous a glacé le sang ! »

Andonis Kalaidzakis se souvient avec émotion de la façon dont, après la mort de Scarpia, Maria a laissé tomber le poignard de sa main et a placé une bougie de chaque côté du tyran mort. Le public a ressenti un frisson d’excitation lorsque Maria a extrait le billet serré dans la main du défunt Scarpia. Puis, elle a fait sa sortie grâce à une autre astuce de mise en scène de Dino Yannopoulos: en sortant par la droite de la scène, sa cape d’hermine jetée sur son épaule et traînant sur le sol derrière elle, elle s’est retournée pour regarder Scarpia mort tandis que le rideau était refermé depuis la gauche de la scène pour terminer l’acte. Le metteur en scène Luschino Visconti a reconnu qu’il avait admiré cette idée ingénieuse. Franco Zeffirelli s’en est inspiré de même que bien plus tard, en 2001, Benoit Jacquot dans son film.

La voix de Maria Callas avait déjà ses propriétés essentielles. Pour le ténor Loudovikos Kourousoupoulos qui a interprété Mario dans les trois représentations chantées en italien, « si vous l’entendiez chanter sans la voir, vous penseriez que ce sont trois personnes différentes qui chantent. Elle avait des difficultés à passer d’un registre à l’autre. Lorsqu’elle atteignait une note aiguë de manière nette, sa voix ne bougeait pas, mais lors d’un portamento vers le haut, elle était affectée d’un trémolo. Cependant, elle avait une telle étendue vocale et une telle chaleur de son, et surtout son jeu d’acteur était si bon, qu’on oubliait ces problèmes. L’effet global était si vivant qu’il vous faisait bondir de votre siège ». Nikos Papachristos, qui faisait partie du chœur, le confirme : « Nous avons été déconcertés et abasourdis par sa voix. Elle avait tellement de couleurs différentes qu’elle manquait d’homogénéité : une voix haute, une voix moyenne et une voix basse, toutes bien distinctes. Mais il y avait une grande fluidité et elle se comportait de manière si naturelle sur scène que l’on oubliait ses défauts vocaux. »

avec Loudovikos Kourousopoulos

Sur la recommandation d’Herbert Graf, Dino Yannopoulos a été nommé metteur en scène principal au MET et il y est resté entre entre 1946 et 1967. Callas l’y a retrouvé pour ses mises en scène de Tosca (en 1956, 1958 et 1965) et de Norma en 1956. Les extraits de la fin de l’Acte II filmés lors du Ed Sullivan Show du 25 novembre 1956 (dir: Dimitri Mitropoulos avec George London, Scarpia) nous donnent une idée de sa mise en scène, avec en particulier, à l’extrême fin, la fameuse sortie de Callas avec sa cape qui traîne sur le sol.

Les photographies comparatives ci-dessous, prises sur scène au cours des répétitions de l’Acte II en 1942 à Athènes avec comme directeur de scène Dino Yannopoulos, et en 1964 à Londres (Covent Garden) dans la mise en scène de Franco Zeffirelli, montrent d’étonnantes similitudes visuelles entre les deux productions prises au tout début (en 1942, elle n’avait pas encore 19 ans) et vers la fin de la carrière scénique de Maria Callas. Sa toute dernière représentation publique d’un opéra a été Tosca à Covent Garden le 5 juillet 1965.

Sur les photos ci-dessous: A gauche: Opéra d’Athènes 1942; A droite: Londres Covent Garden 1964

Acte II Tosca/Scarpia – A gauche: avec Titos Xirellis ; A droite: avec Tito Gobbi

_______

Acte II Tosca/Mario – A gauche: avec Antonis Delendas ; A droite: avec Renato Cioni

______

Acte II – ‘Vissi d’arte’

______

Acte II Tosca/Scarpia – A gauche: avec Titos Xirellis ; A droite: avec Tito Gobbi

______

N.B. Certaines sources indiquent que Maria Callas aurait chanté Tosca à Athènes en juillet 1941 pour remplacer une cantatrice malade. Cette information est erronée. Il n’y a pas eu de représentations de Tosca au Théâtre National en 1941. Ce n’est qu’en 1942 avec la nouvelle production que Tosca a commencé à y être représenté.