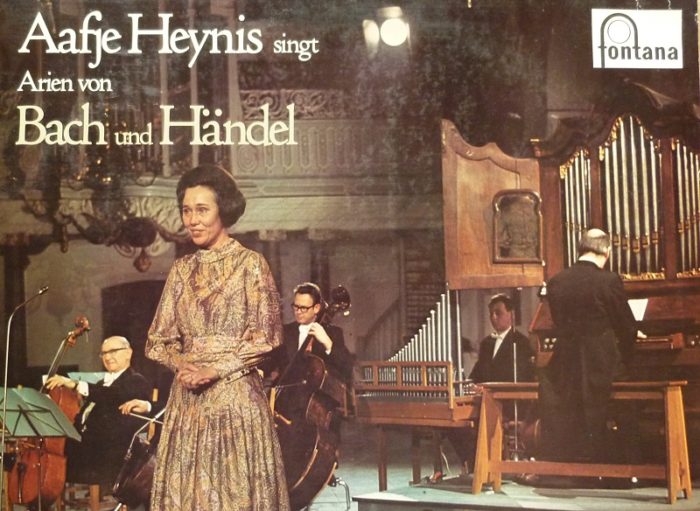

Aafje Heynis, contralto – Wiener Symphoniker (WSO) dir: Hans Gillesberger

Johann Sebastian Bach

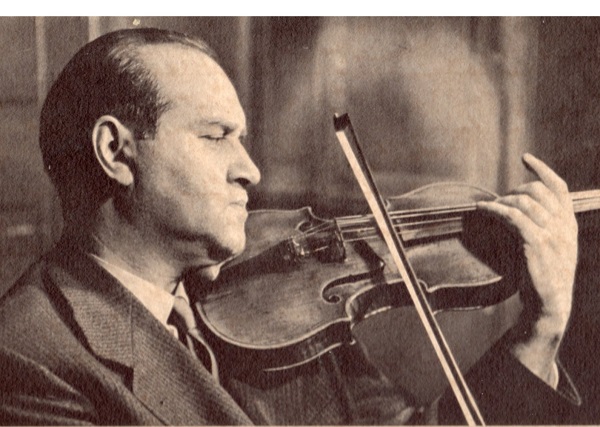

Matthäus-Passion BWV 244: Erbarme dich (Walter Schneiderhan, violon)

Weinachtsoratorium BWV 248: Bereite dich Sion

Johannes-Passion BWV245: Es ist volbracht (Nikolaus Hübner, violoncelle)

Messe h-moll BWV 232: Agnus Dei

Georg Friedrich Händel

Messiah: He was despised – O thou that tellest

Judas Maccabaeus: Father of Heaven

Samson: Return, o God of Hosts

Wien Juli 1960 (Bach), April 1961 (Händel)

La contralto néerlandaise Aafje Heynis (1924-2015) avait un timbre qui rappelait beaucoup celui de Kathleen Ferrier avec laquelle on la confondait souvent. Elle était une interprète incomparable de Bach et de Händel, et il est étonnant que, pour ses enregistrements intégraux des Passions de Bach avec l’ Orchestre du Concertgebouw, Eugen Jochum lui ait préféré la prosaïque Marga Höffgen.

Ces enregistrements n’en sont que plus précieux. Il serait par ailleurs souhaitable que son intégrale de la Matthäus-Passion au Festival de Naarden (12 avril 1960) sous la direction d’Anthon van der Horst soit rééditée.

The voice of the Dutch contralto Aafje Heynis (1924-2015) was very similar to Kathleen Ferrier’s and she was often mistaken for her. She was an outstanding interpret of Bach and Händel, and it is astonishing that, for her complete recordings of the Bach Passions with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, Eugen Jochum chose the rather prosaïc Marga Höffgen.

These recordings are all the more treasurable. A re-issue of her complete performance of the Matthäus-Passion from the Naarden Festival (12 April 1960) under the direction of Anthon van der Horst would be highly wishable.

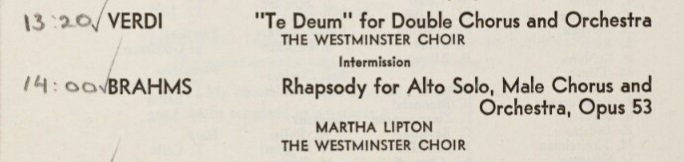

Brahms: Tragische Ouverture Op.81 NBC SO Manhattan Center – January 15, 1951

Brahms: Symphonie n°1 Op.68 NBC SO – Carnegie Hall – December 6, 1952

______

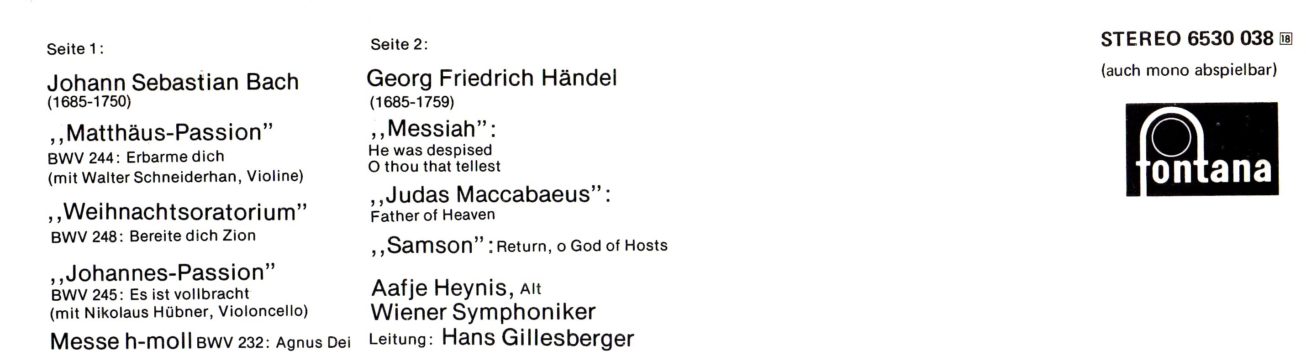

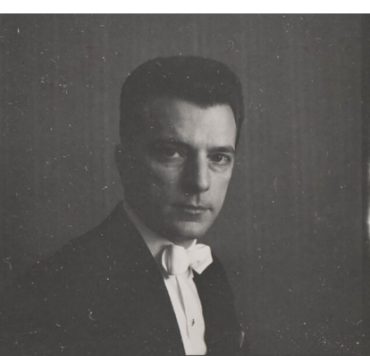

NYPO – Westminster Choir – Carnegie Hall – April 1, 1956

Verdi: Te Deum

Brahms: Alt-Rhapsodie Op.53 NYPO – Martha Lipton

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Guido Cantelli a peu donné en concert l’Ouverture Tragique de Brahms Op.81, mais par contre sa Première Symphonie Op.68 est l’œuvre qu’il a le plus dirigé. Fin 1950, la NBC a transformé en studio de TV le studio 8-H où avaient lieu la plupart des concerts du NBC SO, et a décidé de les transférer au Manhattan Center, salle à l’acoustique très réverbérée, ce que Toscanini a refusé, seul Carnegie Hall étant pour lui acceptable, et donc seuls d’autres chefs d’orchestre, dont Cantelli, y ont donné temporairement des concerts avec cet orchestre, et la NBC n’a finalement pu que se plier à sa demande.

Le Te Deum de Verdi et la Rhapsodie pour contralto, chœurs d’homme et orchestre Op.53 de Brahms ont été mis au programme des concerts des 29, 30, 31 mars, et 1 avril 1956 du New York Philharmonic et c’est la seule fois qu’il les a dirigées.

Guido Cantelli has seldom performed Brahms’ Tragic Overture Op.81, whereas his first Symphony Op.68 was the work he most conducted. At the end of 1950, the NBC transformed Studio 8-H where most of the NBC SO concerts were given, into a TV studio, and decided to tranfer them to Manhattan Center, a venue with much reverberation, which Toscanini refused, only Carnegie Hall being acceptable to him, and thus only other conductors, among them Cantelli, temporarily gave concerts there with this orchestra and eventually the NBC had to comply with his demand.

Verdi’s Te Deum and Brahms’ Rhapsody for contralto, male chorus and orchestra Op.53 were performed at the New York Philharmonic concerts of March 29, 30, 31 and April 1, 1956 and it it the only time he performed them.

Sonate n°1 Op.12 n°1: Vladimir Yampolsky, piano (Prague 26 avril 1954) Supraphon ALPV 244

Sonate n°3 Op.12 n°3: Vladimir Yampolsky, piano (Bruxelles 19 &20 mai 1955) Angel 35331

Sonate n°4 Op.23: Alexander Goldenweiser, piano (Moscou 17 avril 1950) Akkord D-07893

Sonate n°5 Op.24: Lev Oborin, piano (Moscou 1950) Akkord D-07894

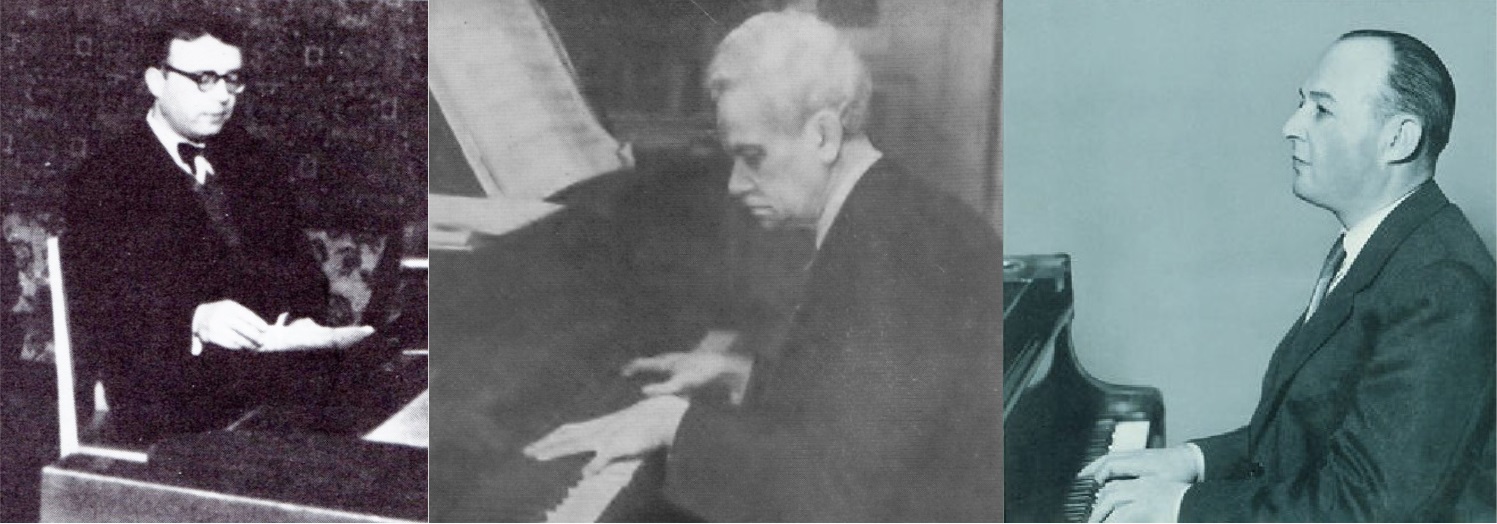

Lev Oborin, Alexander Goldenweiser & Vladimir Yampolsky

David Oïstrakh, né à Odessa (Ukraine) en 1908 et décédé à Amsterdam (Pays-Bas) en 1974, a enregistré à Paris en mai-juin 1962 avec le pianiste Lev Oborin (1907-1974) une célèbre intégrale des Sonates violon-piano de Beethoven après les avoir données en concert à la Salle Pleyel. Cet ensemble a fait l’objet de nombreuses rééditions à tel point que l’on a quasiment oublié l’existence de disques antérieurs. Aussi bien ces enregistrements de studio que les enregistrements des concerts (publiés par Doremi) montrent que ces interprétations sont en retrait par rapport aux enregistrements précédents d’Oïstrakh de huit de ces sonates réalisés entre 1949 et 1955 avec au piano Vladimir Yampolsky (1905-1965) pour les sonates n°1 et 3, Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961) pour la sonate n°4 et Lev Oborin (1907-1974) pour les cinq autres (n°5, 7 , 8, 9 et 10).

Si quatre d’entre elles (n°4, 5, 7 et 8) ont été enregistrées à Moscou, les quatre autres (n°1, 3, 9 et 10) l’ont été respectivement à Prague (pour Supraphon), à Bruxelles (pour EMI), à Paris (pour Le Chant du Monde) et à New-York (pour Columbia), et cette multiplicité d’éditeurs n’a pas permis une publication globale de cette quasi-intégrale.

Or, en dépit de la présence de trois pianistes différents et d’une dispersion des dates ainsi que des lieux et donc aussi des équipes d’enregistrement, on constate une grande homogénéité entre ces interprétations, ce qui signe l’indépendance d’esprit de David Oïstrakh. Nous vous les proposons en trois groupes à partir des microsillons d’origine.

____________

David Oïstrakh, born in Odessa (Ukraine) in 1908 and deceased in Amsterdam (Netherland) in 1974, has recorded in Paris in May-June 1962 with pianist Lev Oborin (1907-1974) a well-known complete version of Beethoven’s violin-piano Sonatas shortly after a series of concerts at Salle Pleyel. It has been re-issued many times so that the very existence of earlier recordings has been almost forgotten. The studio recordings as well as the concert performances (released by Doremi) show that these are much less convincing that the earlier Oïstrakh recordings of eight of the sonatas made between 1949 and 1955 with pianists Vladimir Yampolsky (1905-1965) for sonatas n°1 and 3, Alexander Goldenweiser (1875-1961) for sonata n°4 and Lev Oborin (1907-1974) for the other five (n°5, 7 , 8, 9 and 10).

If four of them (n°4, 5, 7 and 8) were recorded in Moscow, the other four (n°1, 3, 9 and 10) were made in Prag (for Supraphon), in Brussels (for EMI), in Paris (for Le Chant du Monde) and in New-York (for Columbia), and this multiplicity of editors did not permit an overall re-issue of this fast complete series.

In spite of three different pianists and of a dispersion of the dates as well as of the recording countries and for that matter also of the recording teams, there is a great homogeneity in the performances which accounts for David Oïstrakh’s independent mind. We propose them in three groups from the original LPs.

David Oïstrakh & Vladimir Yampolsky

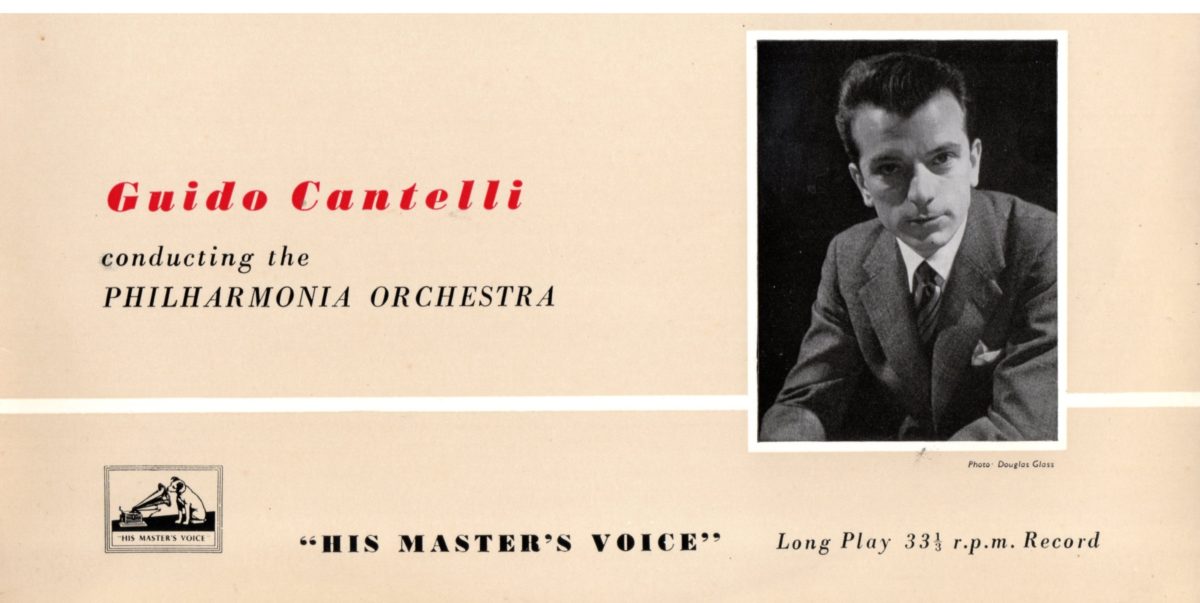

NBC SO Carnegie Hall – 15 December 1951 (Bande/Tape)

_________

Philharmonia Orchestra – 8, 9, 12, 16 &18 August 1955 (GHLP 1004-Mono)

La Troisième Symphonie est réputée comme étant la Symphonie de Brahms la plus difficile à interpréter. Si des chefs comme Walter ou Furtwängler ont signé des versions considérées comme des références, elle a posé beaucoup de problèmes même à de grands brahmsiens, à commencer par Toscanini qui, dans ses témoignages enregistrés, ne l’a vraiment réussie qu’avec le Philharmonia Orchestra, en concert à Londres au Royal Festival Hall en 1952.

C’était par contre une des grandes interprétations de Guido Cantelli qui en a laissé trois témoignages enregistrés (NBC SO, Boston SO, Philharmonia Orchestra).

L’enregistrement réalisé pour HMV/EMI à Kingsway Hall en 1955 a été capté à la fois en monophonie et en stéréophonie expérimentale. A cet effet , il y avait deux équipes de prises de son. L’enregistrement stéréophonique n’a été publié qu’en 1978, et depuis, c’est cette seule version qui est rééditée. Toutefois, en comparant ces deux captations, on constate qu’avec l’étalement en largeur de l’orchestre procuré par la stéréo, la réverbération de Kingsway Hall tend à diluer les timbres et à lisser les phrasés, alors que la prise de son mono, bénéficiant d’un judicieux placement microphonique qui permet à l’acoustique ample de la salle de porter pleinement le son de l’orchestre, est bien mieux définie: l’interprétation sonne de manière nettement plus vivante, et les timbres et les détails du phrasé sont mieux restitués. Avec la version mono, on est aussi musicalement plus proche de la version enregistrée en concert avec le NBC SO.

Le tableau des minutages ci-dessous montre qu’en studio avec le Philharmonia, et comme c’était en général le cas avec Cantelli, les tempi sont plus larges. Il montre aussi qu’en concert, Cantelli faisait la reprise (environ 3′) dans le premier mouvement, mais que cette reprise est malheureusement omise dans l’enregistrement commercial avec le Philharmonia.

Minutages/Timings:

NBC SO 15 Dec. 1951 (12’23; 7’57; 5’35; 8’06)

Boston SO 25 Dec. 1954 (12’28; 7’58; 5’45; 8’02)

NYPO 20 Jan. 1955 (12’40; 7’45; 5’40; 8’10)

Philharmonia Orch Aug. 1955 (9’57; 8’43; 6’18; 8’25)

[Philharmonia Orch Toscanini 1 Oct 1952 (12’27; 8’31; 6’17; 8’34)]

Cantelli Philharmonia Edinburgh

Among the Brahms Symphonies, the Third Symphony is considered as being the most difficult to perform. If conductors like Walter or Furtwängler have made recordings considered as references, it proved problematic even for great Brahms conductors, and for Toscanini to start with, who in his recorded testimonies was only successful with his 1952 London concert in Royal Festival Hall with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

On the other hand, it was one of the great performances of Guido Cantelli who left three recordings (NBC SO, Boston SO, Philharmonia Orchestra).

The 1955 recording for HMV/EMI in Kingsway Hall was made both in mono and in experimental stereo. For this purpose, there where two recording teams. The stereophonic version was published only in 1978, and since then, is the only one to be re-issued. However a comparison between both reveals that, because of the Kingsway Hall reverberation, the spreading in width of the orchestra brought by stereophony goes with a lower definition of the timbres and a smoothing of the phrasings, whereas the mono version, because of a well chosen microphone placement that allows the warm hall acoustics to bring a full-blooded orchestral sound, has much more definition: the performance sounds much more alive, and the timbres and the details of phrasing are better reproduced. With the mono version, we are also musically closer to the concert performance recorded with the NBC SO.

The timings (see above) show that in studio with the Philharmonia, and as was generally the case with Cantelli, the tempi are broader. They also show that, in live performances, Cantelli made the first movement repeat (about 3′), but that this repeat was omitted in the commercial recording with the Philharmonia.

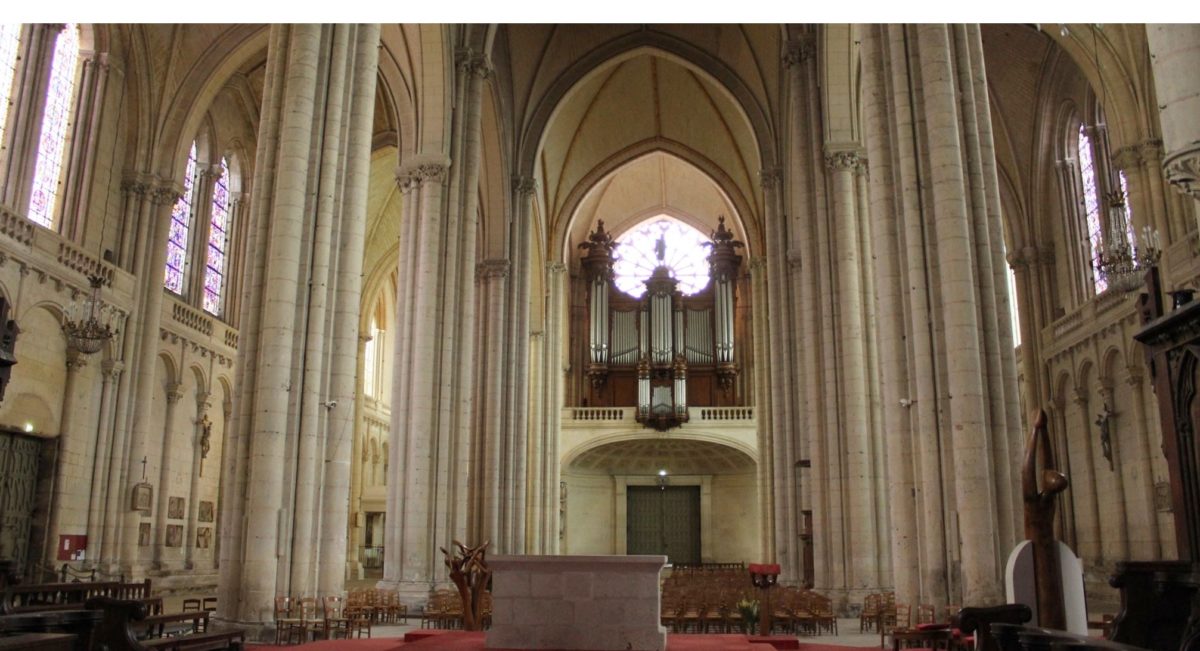

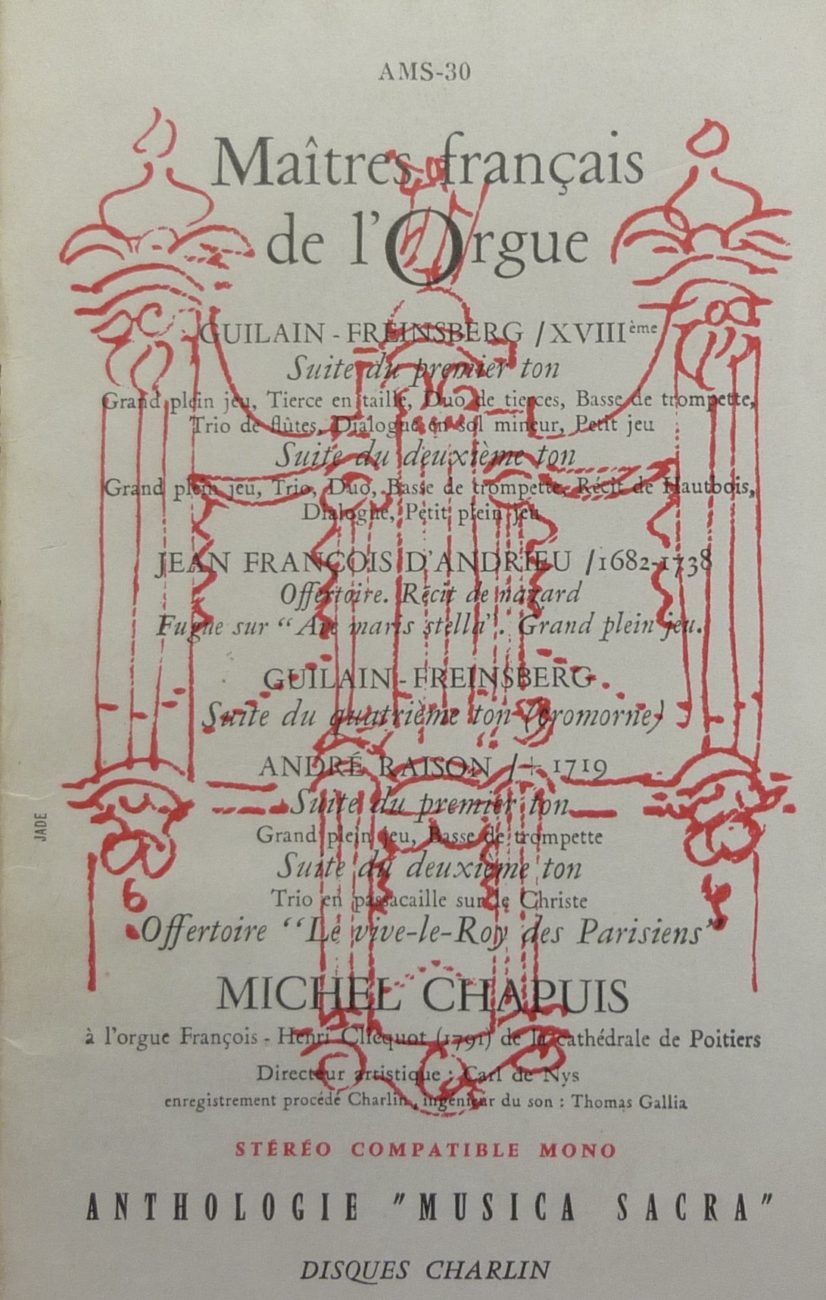

Michel Chapuis à l’Orgue François-Henri Clicquot de la Cathédrale de Poitiers

Enregistré en juillet 1961 (procédé Charlin) par Thomas Gallia (Disque Charlin AMS-30)

01-07 Jean Adam Guilain-Freinsberg Suite du Premier Ton: Grand plein jeu – Tierce en taille – Duo de Tierces – Basse de trompette – Trio de flûtes – Dialogue en sol mineur – Petit jeu

08-14 Jean Adam Guilain-Freinsberg Suite du Deuxième Ton: Grand plein jeu – Trio -Duo – Basse de trompette – Récit de hautbois – Dialogue – Petit plein jeu

15-18 Jean-François D’Andrieu: I Offertoire – II Récit de Nazard – III Fugue sur « Ave Maris Stella » – IV Grand plein jeu

19 Jean Adam Guilain-Freinsberg Suite du Quatrième Ton: Cromorne

20-21 André Raison Suite du Premier Ton: Grand plein jeu – Basse de trompette

22 André Raison Suite du Premier Ton: Trio en passacaille sur le Christe

23 André Raison: Offertoire sur le Vive-le-Roy des Parisiens

L’orgue François-Henri Clicquot (1791) de la Cathédrale de Poitiers (4 claviers et pédalier – 44 jeux – la = 394 Hz), est le seul grand instrument de facture Clicquot qui ait été conservé quasiment intact. Il a certes subi un certain nombre de modifications au cours du XIXème siècle (passage au tempérament égal; pédalier à l’allemande et nouvelle soufflerie en 1871) et au XXème siècle (électrification de la soufflerie en 1926, pédalier moderne en 1954), mais les projets de changements drastiques, comme ceux d’Aristide Cavaillé-Coll pour le transformer en orgue symphonique, ont heureusement échoué par manque de crédits.

La description ci-dessus correspond à l’état de l’orgue pour cet enregistrement de 1961, le tout premier à avoir été réalisé sur cet instrument d’exception, et également le premier microsillon complet de Michel Chapuis (1930-2017), pionnier de la pratique alors contestée des notes inégales et des ornements*.

Michel Chapuis en 1960

L’entretien de l’orgue est assuré depuis 1927 par le facteur Robert Boisseau de Poitiers assisté de son fils Jean-Loup. Ce dernier, sous l’impulsion de l’organiste Jean-Albert Villard, titulaire de l’orgue de 1950 à 2000, mène à bien (avec Bertrand Cattiaux) le grand relevage, de 1988 à 1994, permet de revenir à un tempérament inégal (avec quatre tierces justes), d’effectuer un nettoyage des tuyaux et d’installer une soufflerie conforme à la facture du XVIIIème siècle. Toutefois, le choix de ce tempérament ne s’avérera pas optimal.

En décembre 1996, Michel Chapuis déclarait à propos de cette restauration: « Pour ma part, l’orgue de la Cathédrale de Poitiers est certainement le plus parfait et le plus beau de notre pays. Avant cette intervention, on avait déjà une idée de ce qu’était le Grand Jeu, les anches sonnaient avec beaucoup de noblesse, mais la partie tuyaux à bouche constituant le fond d’orgue et les pleins jeux ne parlaient plus que partiellement. C’est une joie maintenant de retrouver tout cet instrument avec toute sa tuyauterie rénovée et j’admire beaucoup la science de Boisseau et de Cattiaux qui ont su retrouver les gestes qui ont permis de régénérer cet instrument. Ces deux facteurs qui sont nés, si j’ose dire, à l’ombre de Clicquot en ont compris parfaitement l’esprit et la technique. »

En 2010, J-L Boisseau installe un pédalier à la française et ajuste le tempérament inégal de l’instrument (mais seulement en décalant l’accord des tierces justes). Enfin, une dernière intervention réalisée par Bertrand Cattiaux à l’automne 2016 permet d’optimiser le tempérament de l’orgue.

*Dans son livre d’entretiens « Plein Jeu », Michel Chapuis a dit: « Dès que ce disque a été diffusé, il a surpris beaucoup de critiques. On an a beaucoup parlé dans les revues et cela m’a amené des élèves étrangers dans ma classe au Conservatoire de Strasbourg. C’est le disque qui m’a fait connaître ».

____________

The 1791 organ of the Poitiers Cathedral, built by François-Henri Clicquot (4 manuals and pedal – 44 stops – A = 394 Hz), is the only great instrument by organbuilder Clicquot to have survived almost intact. There were indeed some modifications during the 19th century (equal temperament; German pedalboard and new wind system in 1871) and the 20th century (electrification of the wind system in 1926, modern pedalboard in 1954), but the projected drastic changes, such as those suggested by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll to turn it into a symphonic organ, happily failed by lack of money.

The above description is that of the organ for this 1961 recording, the first one made of this outstanding instrument, and also the first complete LP recorded by Michel Chapuis (1930-2017), pionner of the then disputed practice of unequal notes and ornaments.

The maintenance of the organ is made since 1927 by the organbuilder Robert Boisseau (Poitiers) together with his son Jean-Loup. The latter, under the impulse of the organist Jean-Albert Villard, titular of the organ from 1950 to 2000, conducts (with Bertrand Cattiaux) the great overhaul from 1988 to 1994, which allows to go back to an unequal temperament (with four straight thirds), to clean the pipes and to install a wind system in keeping with the 18th century practice. However, the choice of this temperament was not considered as optimal.

In december 1996, Michel Chapuis declared about this restoration: « For me, the organ of the Poitiers Cathedral is certainly the most perfect and the most beautiful in our country. Before this overhaul, we already had an idea of was the « Grand Jeu » was, the reed pipework sounded with great nobility, but the flue stops constituting the « fond d’orgue« and the « Pleins Jeux » only spoke partly. It is now a joy to rediscover this instrument with all of its pipework renovated and I admire very much the science of Boisseau and of Cattiaux who knew how to rediscover the skill that allowed to regenerate this instrument. These two organbuilders who were born, if I dare say, at the shadow of Clicquot have perfectly understood his spirit and his technique. »

In 2010, J-L Boisseau installs a French pedalboard and adjusts the unequal temperament of the instrument (but only by shifting the tuning of the straight thirds). Then, a last intervention conducted by Bertrand Cattiaux in autumn 2016 leads to an optimization of the temperament of the organ.

*In his Book « Plein Jeu », comprised of interviews, Michel Chapuis said: « As soon as this record was published, many critics were surprised. It was much debated in musical reviews and this brought foreign students to my class at the Strasbourg Conservatoire. It is through recordings that I became known ».