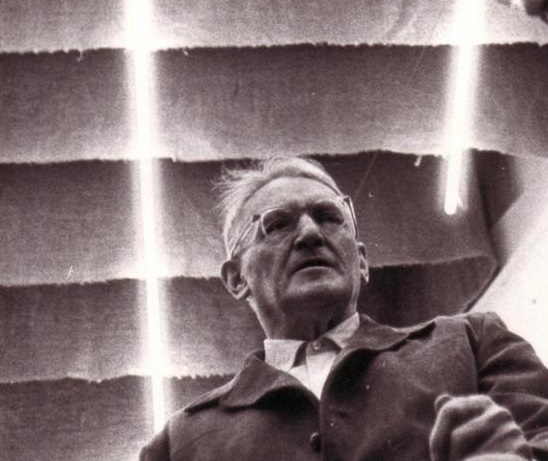

Hermann Scherchen Toronto Symphony Orchestra

Toronto Massey Hall – 22 April 1965

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

En 1965, le Toronto Symphony Orchestra a mis à son programme la Septième Symphonie de Mahler, pour en donner la Première au Canada. Le chef qui devait la diriger, Heinz Unger (1895-1965), spécialiste de Mahler établi à Toronto et bien oublié de nos jours, étant brusquement décédé le 25 février, il a été fait appel à Hermann Scherchen qui, à cette occasion, a dirigé pour la première fois au Canada.

On connaît surtout deux enregistrements de cette symphonie par Scherchen, l’un fait pour la Radio en 1950 avec le WSO, et l’autre en 1953, avec l’Orchestre du Staatsoper pour la firme Westminster. Si le premier pose des options interprétatives intéressantes, on y perçoit un manque assez gênant de répétitions, alors que le deuxième est une des meilleures versions discographiques.

Depuis cette date, Scherchen a évolué, aussi bien par ses expériences dans ses studios de Gravesano que par l’interprétation de la musique contemporaine jusqu’à Xenakis, et pour le concert de Toronto, ses réflexions l’ont conduit beaucoup plus loin. Cette interprétation tendue, à nulle autre pareille, repose sur des tempi rapides* et pousse les musiciens dans leurs retranchements, et elle propulse l’œuvre dans le XXème siècle en la rendant clairement proche de Schoenberg**. Scherchen excelle à créer dès le début du premier mouvement un climat hallucinant qu’il prolonge ensuite dans les trois mouvements nocturnes qui forment le volet central.

La retransmission du concert est précédée d’une introduction au cours de laquelle est diffusée une brève interview du chef d’orchestre par le compositeur canadien Harry Somers (1925-1999).

* Dans l’édition Bote und Bock de 1909, aussi bien que dans les programmes de concert dirigés par Mahler (Concertgebouw 2, 3 et 7 octobre 1909), Mengelberg (NYPO 8 & 9 mars 1923) et Mitropoulos (NYPO 11 & 12 novembre 1948), la partie Allegro du premier mouvement est désignée comme « Allegro con fuoco », ce qui est très différent de l’indication « Allego risoluto ma non troppo » qui est maintenant usuelle . L’interprétation de Scherchen est résolument « con fuoco »!

** Après les concerts de Mitropoulos de novembre 1948 avec cette œuvre, curieusement couplée avec le Concerto Champêtre de Poulenc avec le compositeur au piano, Olin Downes, qui en fait a quitté le concert au milieu du troisième mouvement de la symphonie, a publié dans le New York Times du 12 novembre 1948 un article au vitriol dénigrant la Symphonie de Mahler comme étant « du mauvais art, de la mauvaise esthétique et de la mauvaise musique, présomptueuse et ouvertement vulgaire ». Cet article a suscité une vigoureuse protestation de la part d’ Arnold Schoenberg qui tenait beaucoup à cette œuvre. Downes a publié cette lettre dans le numéro du 12 décembre, mais dans sa réplique, il n’a rien changé à son opinion.

____________

Pistes/Tracks:

01- Annonce/Announcement Interview Hermann Scherchen (Harry Somers)

02- I Langsam Adagio Allegro risoluto ma non troppo

03- II Nachtmusik I Allegro moderato

04- III Scherzo Schattenhaft (Fliessend, aber nicht schnell)

05- IV Nachtmusik II Andante amoroso

06- V Rondo-Finale Tempo I (Allegro ordinario) Tempo II (Allegro moderato ma energico)

07- Désannonce/Announcement

____________

In 1965, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra decided to premiere in Canada Mahler’s Seventh Symphony. The conductor who was hired to conduct it, Heinz Unger (1895-1965), a Mahler specialist living in Toronto, who is now sadly forgotten, unexpectedly died on February 25. Hermann Scherchen was called, and this was the first time he conducted in Canada.

Two recordings of this symphony by Scherchen are best known: one made for in 1950 for the Radio with the WSO, and the other one in 1953, with the Staatsoper Orchestra for Westminster. If the first one sets interesting performing options, the performance is marred by a noticeable lack of rehearsals, whereas the second one is one of the best recordings of the work.

Since that time, Scherchen has evolved, because of his experiments in his Gravesano studios as well as his interpretation of contemporary music up to Xenakis, and for the Toronto concert, his thoughts led him much further. This tense performance, which is unlike any other, is based on fast tempi* that bring the musicians to their utmost, and it propels the work well into the le XXth century, making it clearly close to Schoenberg**. Scherchen excells in creating from the start of the first movement an hallucinatory atmosphere which he further extends to the three nocturnal movements that constitute the central part.

The concert broadcast starts with an introduction including a brief interview of the conductor by Canadian composer Harry Somers (1925-1999).

* In the 1909 Bote und Bock printed score as well as in the printed concert programs conducted by Mahler (Concertgebouw 2, 3 & 7 October 1909), Mengelberg (NYPO 8 & 9 March 1923) and Mitropoulos (NYPO 11 & 12 November 1948), the Allegro part of the first movement is named « Allegro con fuoco », which is very different from the now used term « Allego risoluto ma non troppo ». Scherchen’s performance is unmistakably « con fuoco »!

** After the Mitropoulos concerts of November 1948 with this work strangely coupled with Poulenc’s Concerto Champêtre with the composer at the piano, Olin Downes, who in fact left the concert in the middle of the third movement of the symphony, published in the New York Times (November 12, 1948) a vitriolic article denigrating Mahler Symphony as being « bad art, bad esthetic and bad, presumptuous, and blatantly vulgar music ». This article fueld a vigorous protest by Arnold Schoenberg for which this work was so important. Downes published his letter in the December 12 issue, but in his response, he changed nothing to his opinion.

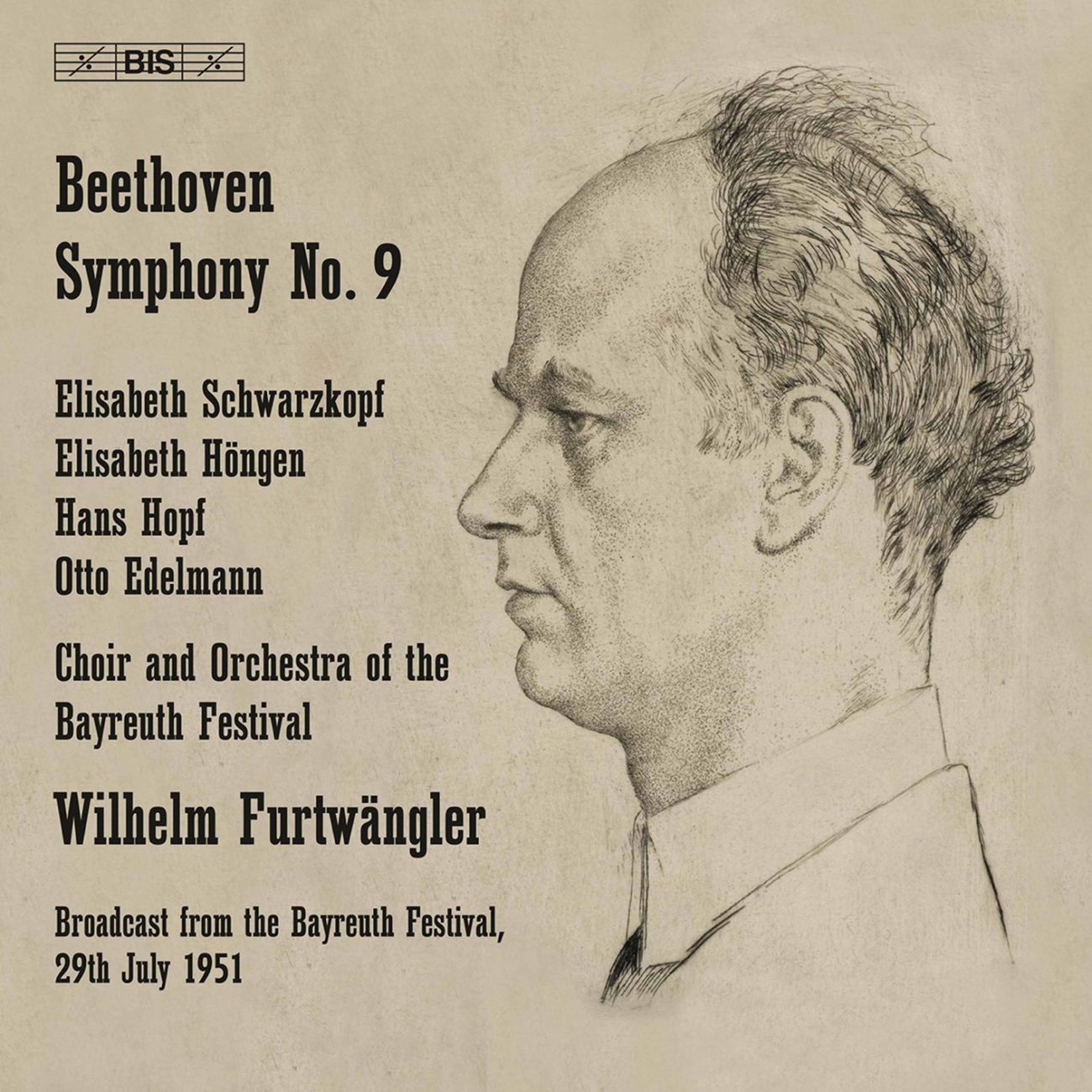

Beethoven Symphony n°9 Op125 Das Festspielorchester – Das Festspielchor Bayreuth

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen,Hans Hopf, Otto Edelmann

Dir: Wilhelm Furtwängler

La firme suédoise BIS vient de mettre en vente sous forme de SACD Hybride (BIS-9060) et de téléchargement HD la captation par la Radio Suédoise de la retransmission en direct de ce concert par la Radiodiffusion Bavaroise (Bayerischer Rundfunk), qui de manière inattendue a été conservée dans ses Archives.

Les négociations entre Wilhelm Furtwängler et Wieland Wagner préalablement à ce concert, la composition de l’orchestre et des chœurs, l’organisation des répétitions, les circonstances techniques de la retransmission et de la captation par la Radio Suédoise, ainsi que le contenu de l’enregistrement publié par EMI sont discutées dans cet article: pour le lire, cliquer ICI

The Swedish record company BIS has recently issued both as a Hybrid SACD (BIS-9060) and as a Hi-Res download (24 bits/96 KHz) the recording made by the Swedish Radio of the Bavarian radio (Bayerischer Rundfunk) live broadcast of this concert, which has unexpetedly survived in its Archives.

The negociations between Wilhelm Furtwängler and Wieland Wagner prior to the concert, how the orchestra and the choir were organized, the rehearsal plan, the technical circumstances of the broadcast and of its recording by the Swedish radio, as well as the content of the recording as published by EMI are discussed in this article: to read it, click HERE

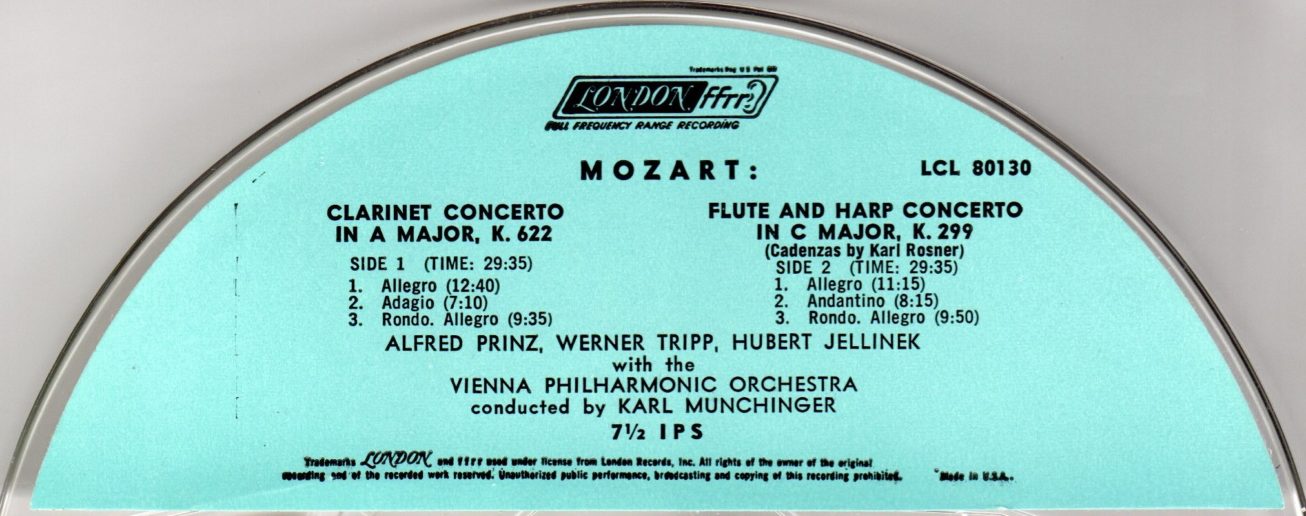

Enregistré à Vienne à la Sofiensaal les 16 (K622) & 19-21 (K299) septembre 1962

Prod: Christopher Raeburn – Eng: James Brown

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Avec trois solistes des Wiener Philharmoniker, voici, sous la baguette de Karl Münchinger, une version privilégiée de ces deux concertos.

Le clarinettiste Alfred Prinz (1930-2014), élève de Leopold Wlach (1902-1956), intègre en 1945 (à 15 ans!) l’orchestre du Wiener Staatsoper. En 1956, il succède à Leopold Wlach en tant que membre des Philharmoniker. Il est 1ère ou 2e clarinette de 1956 à 1964, et 1ère clarinette de 1964 à 1984, puis 2e clarinette jusqu’à sa retraite en 1995.

Le flûtiste Werner Tripp (1930-2003) quitte en 1955 l’orchestre de Graz pour intégrer l’orchestre du Wiener Staatsoper (2e flûte). Il devient membre des Philharmoniker en tant que flûte solo en 1961, poste qu’il conservera jusqu’à sa démission en 1977.

Le harpiste Hubert Jelinek (1909-1980) intègre le Staatsoper et les Philharmoniker en 1936, où il reste jusqu’à sa retraite en 1974.

N.B. L’orthographe admise est Jelinek plutôt que Jellinek.

With three soloists from the Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO), here is, with Karl Münchinger conducting, a privileged version of these two concertos.

Clarinettist Alfred Prinz (1930-2014), pupil of Leopold Wlach (1902-1956) joins in 1945 (at the age of fifteen!) the orchestra of the Wiener Staatsoper. In 1956, he succeds Leopold Wlach (1902-1956) as a member of the Philharmoniker. He is 1st or 2nd clarinet from 1956 to 1964, and 1st clarinet from 1964 to 1984, then 2nd clarinet until his retirement in 1995.

Flutist Werner Tripp (1930-2003) leaves in 1955 the Graz orchestra to join the orchestra of the Wiener Staatsoper (2nd flute). He becomes member of the Philharmoniker as solo flute in 1961, and remains at this post until his resignation in 1977.

Harpist Hubert Jelinek (1909-1980) joins the Staatsoper and the Philharmoniker in 1936, where he remains until his retirement in 1974.

N.B. The acccepted spelling is Jelinek rather than Jellinek.

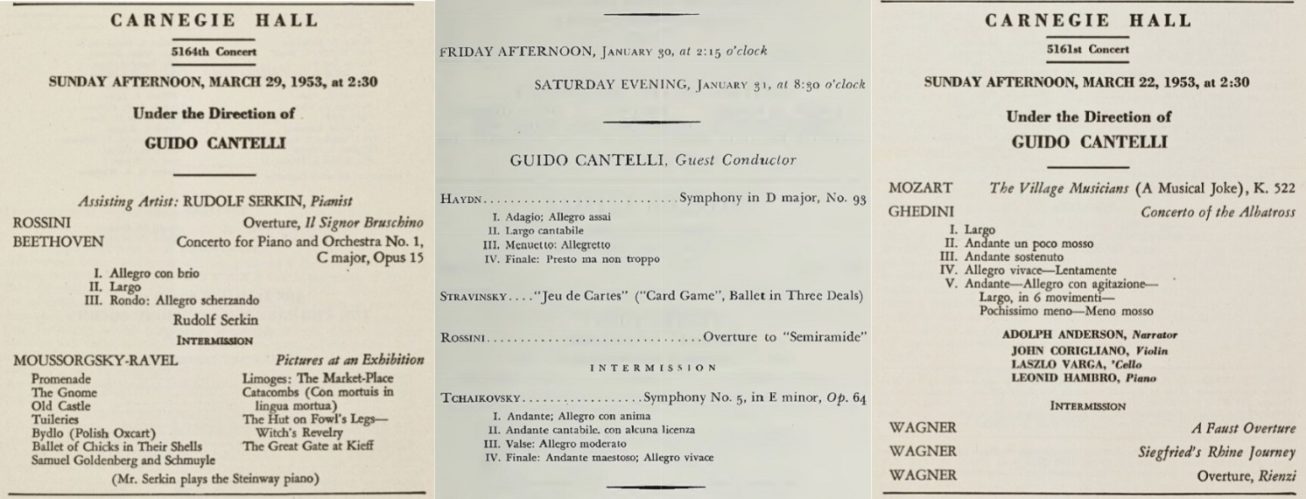

Meilleurs Vœux pour 2022 avec/ Best Wishes for 2022 with:

Rossini

Il Signor Bruschino – NYPO Carnegie Hall 29 mars 1953

Cenerentola – NBC SO Carnegie Hall 14 février 1954

Semiramide – BSO Boston Symphony Hall 31 janvier 1953

_____

Verdi La Forza del Destino NBC SO Carnegie Hall 2 février 1952

Wagner Faust-Ouvertüre NYPO Carnegie Hall 22 mars 1953

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

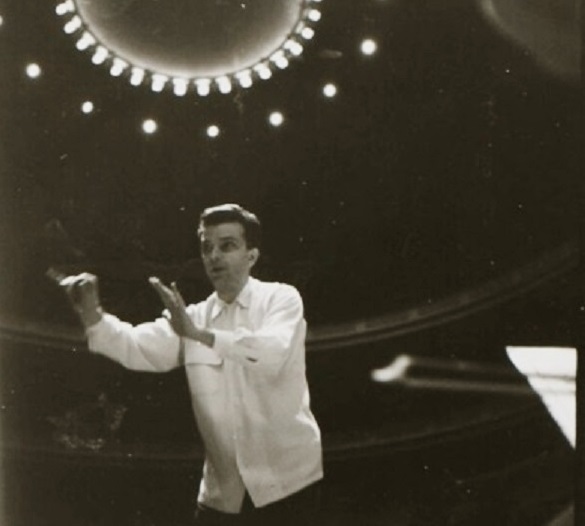

Voici pour débuter cette année cinq ouvertures interprétées avec trois orchestres (New York Philharmonic; NBC Symphony Orchestra; Boston Symphony Orchestra) pour lesquelles les interprétations de Cantelli se situent dans le droit fil de Toscanini. On notera cependant qu’il y a ici plus de respiration et de souplesse, et que l’enthousiasme y est celui de la jeunesse. Mais Toscanini lui-même ne disait-il pas de Cantelli que c’était lui quand il était jeune?

L’ouverture qu’il a le plus jouée était Semiramide, depuis le Festival d’Edimbourg 1950 (le 6 septembre) avec l’orchestre de la Scala: il en reste un bref extrait de 3’45 filmé en répétition à Usher Hall (pour un extrait d’une minute, cliquer ICI ), jusqu’à son tout dernier concert le 17 novembre 1956 à Novara avec ce même orchestre.

_____________

For the beginning of this New Year, here are five Overtures performed with three orchestras (New York Philharmonic; NBC Symphony Orchestra; Boston Symphony Orchestra) in which Cantelli’s performances are in line with Toscanini’s. There are, it is worth noting, more breathing and flexibility, and the enthusiasm is that of youth. But didn’t Toscanini himself say that Cantelli was like himself when he was young?

The Overture he performed most was Semiramide, since the 1950 Edinburgh Festival (September, 6) with the Scala Orchestra, of which remains a short filmed 3’45 rehearsal excerpt shot in Usher Hall (click HERE for one minute thereof), until his very last concert on November, 17, 1956 in Novara, with the same orchestra.

Guido Cantelli: NYPO March 29, 1953 – BSO Jan. 30 & 31, 1953 – NYPO March 22, 1953

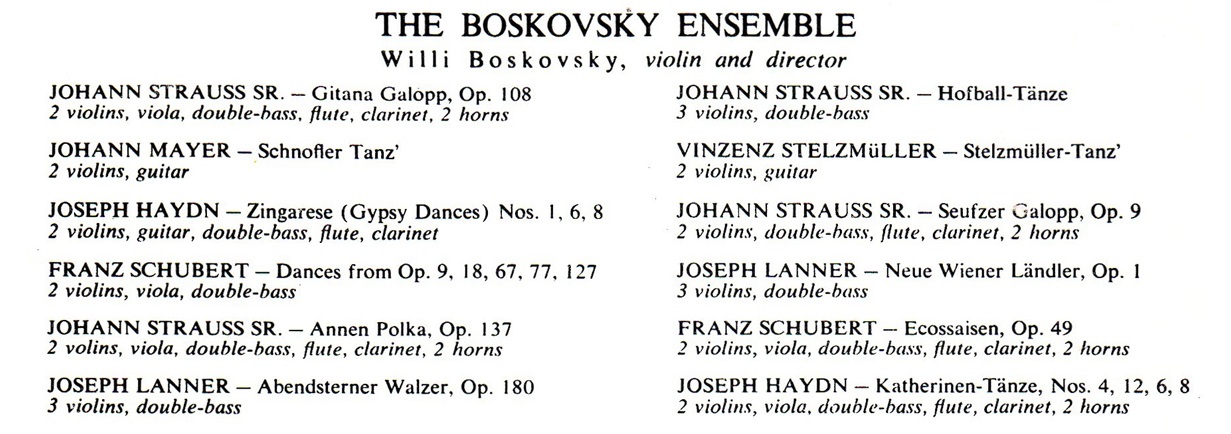

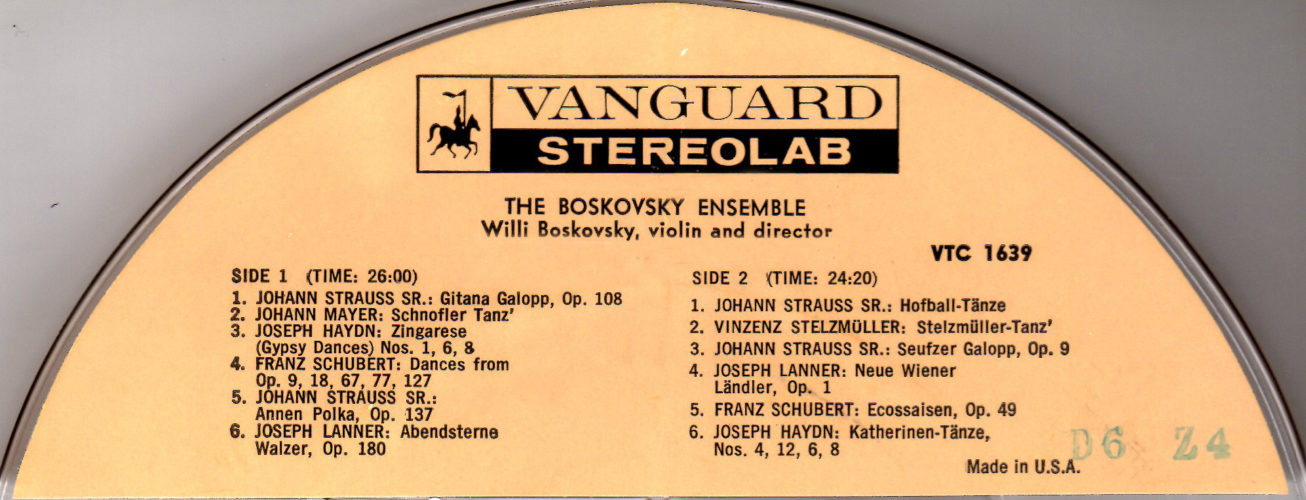

Boskovsky Ensemble – II

Œuvres de Haydn, Schubert, Lanner, Mayer, Stelzmüller et de J. Strauss Sr.

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips VTC 1639

Boskovsky Ensemble (membres du WPO, sauf le pupitre de guitare):

Violon I : Willi Boskovsky (1908-1991) « Stimmführer » des violons I de 1934 à 1938, puis Konzertmeister de 1938 à 1970

Violin II : Wilhelm Hübner (1914-1996) « Stimmführer » des violons II de 1954 à 1964, « Vorgeiger » ensuite jusqu’en 1980 (retraite)

Violin III et Alto: Rudolf Streng (1915-1988) violon I de 1938 à 1959; alto solo de 1959 à 1980 (retraite)

Contrebasse: Otto Rühm (1906-1979) contrebasse solo de 1955 à 1971 (retraite)

Flûte: Josef Niedermayr (1900-1962) flûte solo de 1933 à 1962

Clarinette: Rudolf Jettel (1903-1981) clarinette solo de 1945 à 1968 (retraite)

Cors: Otto Nitsch (1906-1982) 2ème cor de 1941 à 1971; Roland Berger(1937) 3ème cor au Wiener Staatsoper (1955); cor solo de 1961 à 1984; de nouveau 3ème cor de 1984 à 1993 (retraite)

Guitare: Alois Pistor (Haydn Zingarese) ; Karl Scheit

01- Johann Strauss Sr. : Gitana Galopp Op.108 pour 2 violons, alto, contrebasse, flûte, clarinette et 2 cors

02- Johann Mayer: Schnofler Tanz’ pour 2 violons et guitare

03- Josef Haydn: Zingarese n°1, 6 & 8 pour 2 violons, guitare, contrebasse, flûte et clarinette

04- Franz Schubert: Danses Op.9 n° 18, 67, 77 & 127 pour 2 violons, alto et contrebasse

05- Johann Strauss Sr. : Annen Polka Op.137 pour 2 violons, alto, contrebasse, flûte, clarinette et 2 cors

06- Josef Lanner: Abendsterner Walzer Op.180 pour 3 violons et contrebasse

07- Johann Strauss Sr. : Hofball Tänze pour 3 violons et contrebasse

08- Vincenz Stelzmüller: Stelzmüller Tanz’ pour 2 violons et guitare

09- Johann Strauss Sr. : Seufzer Galopp Op.9 pour 2 violons, contrebasse, flûte, clarinette et 2 cors

10- Josef Lanner: Neue Wiener Ländler Op.1 pour 3 violons et contrebasse

11- Franz Schubert: Ecossaisen Op.49 pour 2 violons, alto, contrebasse, flûte, clarinette et 2 cors

12- Josef Haydn: Katherinen Tänze n° 4, 12, 6 & 8 pour 2 violons, alto, contrebasse, flûte, clarinette et 2 cors

L’enregistrement a été réalisé en 1961 dans la Festsaal du Casino de Baumgarten.

The recording was made in 1961 in the Festsaal of the Baumgarten Casino.

____________

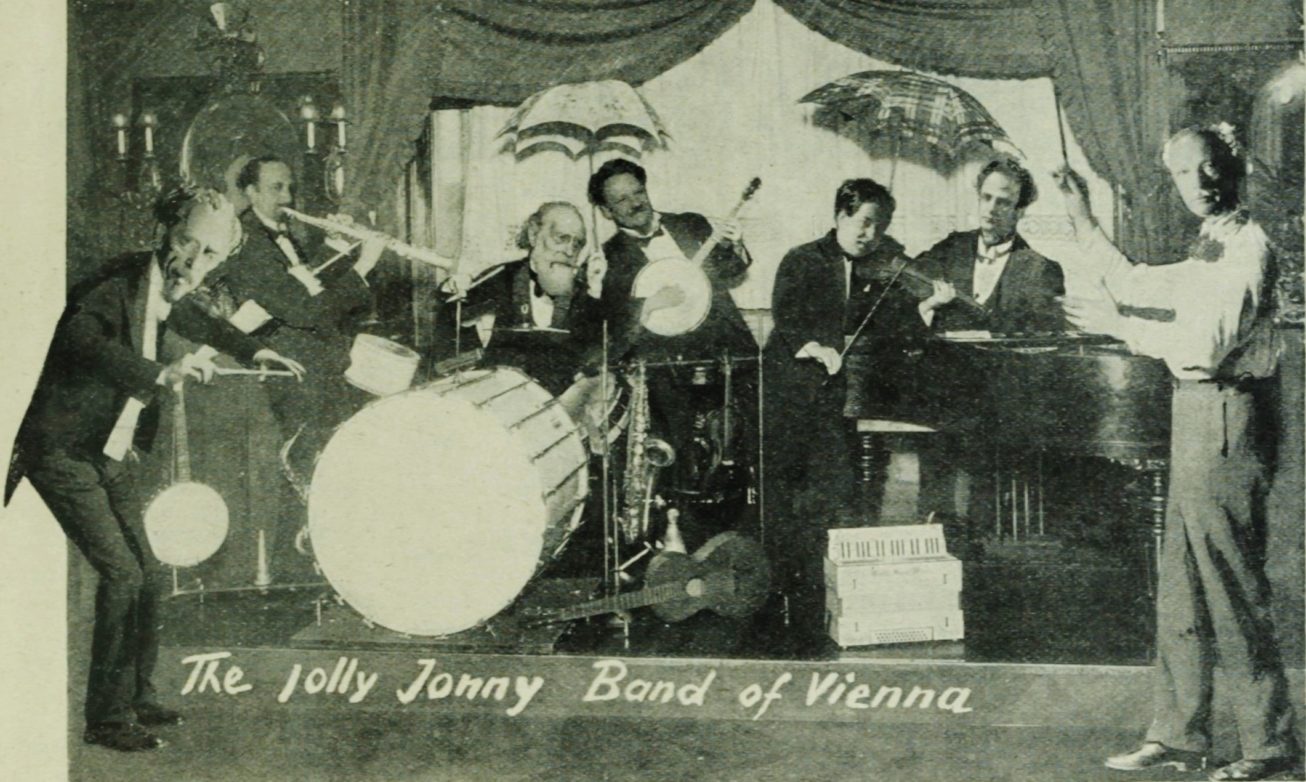

La tradition des petits ensembles de musique populaire viennoise date de bien avant le très officiel concert du Nouvel An donné par les Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO). Avec le Boskovsky Ensemble, les membres du WPO nous prouvent qu’ils maîtrisaient parfaitement ce style.

Comme montre la photo ci-dessous qui date de 1927, cette tradition ne se limitait pas du tout à la musique viennoise. On remarque que, pour ce répertoire inhabituel, il a été fait appel à non pas un, mais deux chefs d’orchestre, choisis parmi les plus prestigieux, Franz Schalk et Richard Strauss!

Franz Schalk; Paul Stefan, flûte; Wilhelm Kienzl, percussion; Leo Slezak, banjo; Erich Wolfgang Korngold, violon; Wilhelm Furtwängler, piano; Richard Strauss (1927)

The tradition of small ensembles of Viennese popular music is much older than the very official New Year concert of the Wiener Philharmoniker (WPO). With the Boskovsky Ensemble, the members of the WPO prove that they perfectly mastered this style.

But as the above picture taken in 1927 shows, this tradition was not at all limited to Viennese music. Worth mentioning is that, for this unusual repertoire, there were not only one, but two conductors, chosen among the most prestigious, Franz Schalk and Richard Strauss!

____________

Boskovsky Ensemble (members of the WPO, except the guitar players):

Violin I : Willi Boskovsky (1908-1991) « Stimmführer » of violins I from 1934 to 1938, then Konzertmeister from 1938 to 1970

Violin II : Wilhelm Hübner (1914-1996) « Stimmführer » of violins II from 1954 to 1964, then « Vorgeiger » until 1980 (retirement)

Violin III and Viola: Rudolf Streng (1915-1988) violin I from 1938 to 1959; solo viola from 1959 to 1980 (retirement)

Double-bass: Otto Rühm (1906-1979) solo double-bass from 1955 to 1971 (retirement)

Flute: Josef Niedermayr (1900-1962) in the orchestra since 1921; solo flute from 1933 to 1962

Clarinet: Rudolf Jettel (1903-1981) solo clarinet from 1945 to 1968 (retirement)

Horns: Otto Nitsch (1906-1982) 2nd horn from 1941 to 1971; Roland Berger(1937) 3rd horn at the Wiener Staatsoper (1955); solo horn between 1961 and 1984; then again 3rd horn between 1984 and 1993 (retirement)

Guitar: Alois Pistor (Haydn Zingarese); Karl Scheit

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.