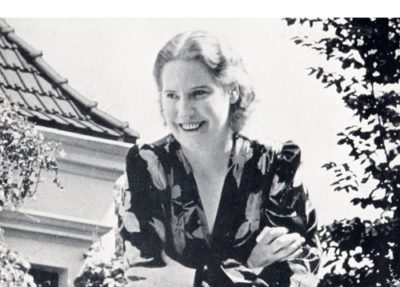

Kirsten Flagstad

Wagner Wesendonck Lieder (Der Engel – Stehe still – Im Treibhaus – Schmerzen – Träume)

Filharmonisk Selskaps Orkester (Orchestra of the Philharmonic Society Oslo)

Dirigent: Øivin Fjeldstad (concert Oslo – Nationaltheatret – Dec. 16, 1951)

33t. Acanta BB 23.189

____

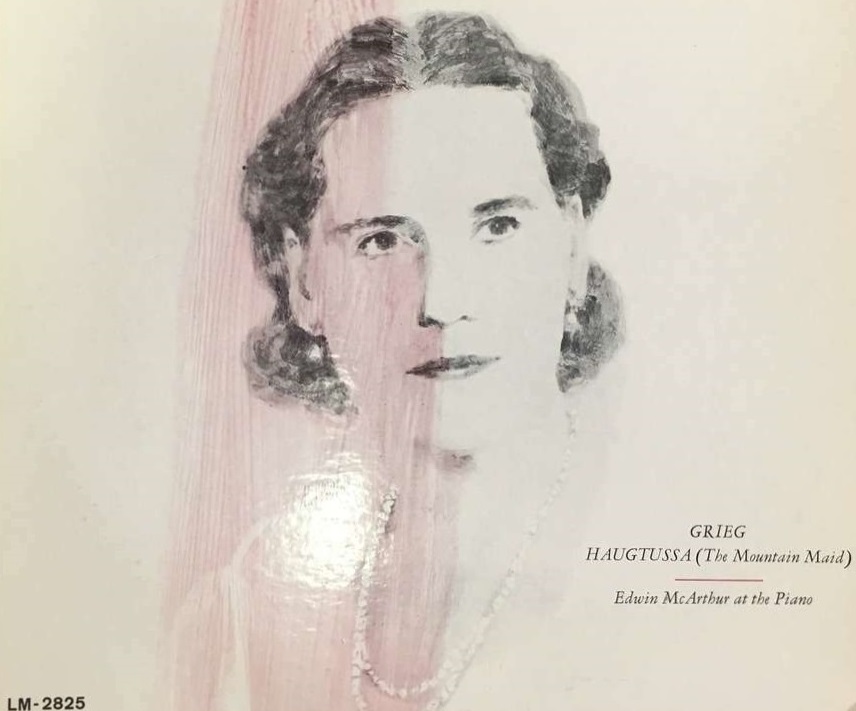

Grieg Haugtussa Op.67 (Det Sing – Veslemöy – Blåbær-Li – Møte – Elsk – Killingdans – Vond Dag – Ved Gjætle-Bekken)

Edwin Mc Arthur, piano ( Los Angeles – April 26, 1950)

33t. RCA LM-2825

Ces deux cycles de mélodies sont ceux que Kirsten Flagstad a le plus donné en concert au cours de sa carrière.

Elle a chanté un nombre incalculable de fois les deux derniers Wesendonck Lieder (Schmerzen, Träume) au cours de ses récitals. Mais ce n’est que le 8 juin 1939 qu’elle a donné pour la première fois le cycle complet lors d’un concert à Zurich à la Villa Wesendonck avec l’Orchestre de la Tonhalle sous la direction de Robert Denzler. Elle l’a ensuite chanté quelque 55 fois, que ce soit dans la version avec piano ou avec orchestre, la dernière fois étant à New-York (Carnegie Hall) le 23 mars 1955 avec l’orchestre « Symphony of the Air » dirigé par Edwin Mc Arthur. Elle a enregistré deux fois le cycle, la première avec Gerald Moore au piano (25 & 26 mai 1948) et la seconde avec le WPO dirigé par Hans Knappertsbusch (Sofiensaal 13 & 15 mai 1956). L’enregistrement de la Radio norvégienne, qui bénéficie de l’accompagnement soigné d’ Øivin Fjeldstad est probablement son meilleur avec orchestre. Son état vocal est notamment meilleur que le 9 mai 1952 avec G. Sébastian au Titania Palast de Berlin, où son timbre, peu de temps avant l’enregistrement de Tristan und Isolde avec Furtwängler, apparaît un peu voilé.

Le cycle Haugtussa Op.67 de Grieg est entré à son répertoire le 13 mars 1940 lors d’un récital à New York (Town Hall) avec le pianiste Edwin Mc Arthur. Elle le chantera ensuite environ 35 fois, la dernière étant à Oslo pour la radio le 16 septembre 1954 avec le pianiste Woldemar Alme. Elle l’a enregistré trois fois avec le pianiste Edwin Mc Arthur: le 27 août 1940 à Los Angeles, le 26 avril 1950, également à Los Angeles, trois jours après un récital donné au Philharmonic Auditorium de cette même ville, et enfin à Londres (22-30 novembre 1956).

En 1950, l’enregistrement de cette œuvre qui lui tenait particulièrement à cœur est d’une très grande chaleur expressive, plus que dans ses deux autres prestations pour le disque.

Ce magnifique cycle composé par Grieg en 1895 ne comporte que huit mélodies. Il raconte le premier déboire amoureux d’une jeune montagnarde, Veslemöy. Les références à la nature des poèmes d’Arne Garborg, auxquelles s’ajoute une pointe de mysticisme, et l’invocation au ruisseau qui conclue le cycle font penser à la « Schöne Müllerin » de Schubert. Si ce chef-d’œuvre est pratiquement oublié de nos jours, c’est probablement à cause de la langue des poèmes, difficilement abordable. Pourtant, Flagstad l’a chanté un peu partout aux Etats-Unis y compris dans des villes moyennes situées hors des circuits habituels des concerts. Avec une traduction, le sens des poèmes est aisé à comprendre.

These two Lieder cycles are those of which Kirsten Flagstad gave the most concert performances during her career.

She sang an innumerable number of times the last two Wesendonck Lieder (Schmerzen, Träume) during her recitals. But it is only on June 8, 1939 that she performed the complete cycle for the first time during a concert at the Villa Wesendonck in Zurich with the Tonhalle Orchester conducted by Robert Denzler. She then sang it about 55 times, either in the version with piano or with orchestra, the last time being in New-York (Carnegie Hall) on March 23, 1955 with the « Symphony of the Air Orchestra » conducted by Edwin Mc Arthur. She recorded it twice, the first time with Gerald Moore at the piano (May 25 & 26, 1948) and the second time with the WPO conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch (Sofiensaal May 13 & 15, 1956). The recording made by the Norvegian Radio, with Øivin Fjeldstad’s refined accompaniment is probably her best with an orchestra. Her vocal condition is notably better than on May 9, 1952 with G. Sébastian at the Berlin Titania Palast, where her timbre, not long before the recording of Tristan und Isolde with Furtwängler, sounds slightly veiled.

The cycle Haugtussa Op.67 by Grieg entered her repertoire on March 13, 1940 during a recital in New York (Town Hall) with pianist Edwin Mc Arthur. She then sang it about 35 times, the last one in Oslo as a Radio broadcast on September 16, 1954 with pianist Woldemar Alme. She made three recordings with pianist Edwin Mc Arthur: on August 27, 1940 in Los Angeles, on April 26, 1950, also in Los Angeles, three days after a recital at the Philharmonic Auditorium of that same city, and then in London (November 22-30, 1956).

In 1950, the recording of this work that was especially dear to her, has a very great expressive warmth, more than in her other two studio renditions.

This magnificent cycle composed by Grieg en 1895 is comprised of only eight melodies. It tells the story of the first unhappy love of a mountain maid, Veslemöy. Arne Garborg’s poems make reference to nature, with a touch of mysticism, and the invocation to the brook that ends the cycle makes one think of Schubert’s « Schöne Müllerin ». If this masterpiece is now almost forgotten, it is probably because the language of the poems is not easy of access. However, Flagstad sang it almost everywhere in the United States, included in middle-sized towns far from the usual path of concert tours. With a translation, the meaning of the poems is easy to comprehend.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

SONY Classical vient d’annoncer la parution prévue en avril 2022 d’un imposant coffret de 69 CD intitulé « Dimitri Mitropoulos – The Complete RCA and Columbia Album Collection ».

C’est un véritable événement , car l’accessibilité de nombre de ces documents historiques était devenu problématique.

Les détails de la composition du coffret sont donnés ici

______________

SONY Classical has just announced the publication in April 2022 of an important Boxset titled: « Dimitri Mitropoulos – The Complete RCA and Columbia Album Collection ».

This is a great event since many of these historical documents had become hard to find.

The details of its content are given here

Dimitri Mitropoulos Kölner Rundfunk Sinfonie Orchester

Lucretia West, mezzo-soprano

Kölner Rundfunkchor dir: Bernhard Zimmermann

Kölner Domchor dir: Adolf Wendel

Köln Funkhaus Saal 1 – 31 Oktober 1960

Source: Bande/Tape 38 cm/s / 15 ips

Lucretia West

Ce fut donc le dernier concert de Dimitri Mitropoulos, qui en dépit de son état de santé, s’était imposé pendant l’été et l’automne 1960 une programmation très chargée, qui est reconstituée ici pour la première fois.

Au Festival de Salzburg 1960, il donne deux concerts triomphaux (Mendelssohn Symphonie n°3, Schoenberg Variations Op.31 et Debussy La Mer le 21 août, et la Symphonie n°8 de Mahler le 28 août). Ensuite, Il dirige au Wiener Staatsoper six représentations (23, 27 et 30 septembre; 7, 12 et 15 octobre) de la Forza del Destino de Verdi qualifiées de géniales par la presse autrichienne, entrecoupées avec les Wiener Philharmoniker de deux programmes à la Musikvereinsaal, d’une part les 1 et 2 octobre (Mahler Symphonie n°9), et d’autre part les 8 et 9 octobre (Schumann Symphonie n°2, Th. Berger Jahreszeiten et Debussy La Mer). Ces deux programmes sont redonnés au cours d’une courte tournée, le 10 à Graz pour le premier, et le 11 à Linz pour le deuxième.

Il se rend ensuite à Cologne pour une série de quatre concerts avec l’Orchestre Symphonique de la WDR (Kölner Rundfunk Sinfonie Orchester).

Le premier de ceux-ci, le 24 octobre, reprend le programme salzbourgeois du 21 août avec le BPO, et le second, le 31 octobre, est donc consacré à cette Troisième de Mahler. Lors du concert du 31, il réussit à surmonter un malaise au cours du premier mouvement, mais il refuse cependant les avis pressants d’interrompre le concert après l’entracte qui suit le premier mouvement, acceptant seulement de diriger assis. En dépit de son état de fatigue extrême, il prend immédiatement après la fin du concert le train de nuit pour Milan où il doit diriger cette même Troisième le 7 novembre avec l’Orchestre de la Scala.

Le soir du 1er novembre, il rédige dans sa chambre d’hôtel milanaise une courte lettre à l’intention de l’épouse de Bruno Zirato*, Nina, qu’il poste le lendemain matin en se rendant à sa répétition avec l’Orchestre de la Scala: « Je suis ici à Milan, malheureux et mort de fatigue, et je m’inquiète de mon état de santé. Le climat de Cologne ne m’a pas fait de bien…. J’étais toujours à court de respiration. Chers amis, priez pour que je puisse retourner à New-York, et qu’ici je ne sois pas obligé d’aller à l’hôpital. Votre malheureux Dimitri ».

Le décès de Mitropoulos au cours de la répétition du 2 novembre a été rapporté dans l’ouvrage de Willam R. Trotter « Priest of Music The Life of Dimitri Mitropoulos« .

Karl O. Hoch (WDR – Leiter der Hauptabteilung Musik) annonce dans son hommage radiophonique que le chef venait d’accepter sa nomination comme Directeur Musical du Kölner Rundfunk Sinfonie Orchester. On ne connaît pas les programmes des deux autres concerts prévus à Cologne les 14 et 21 novembre.

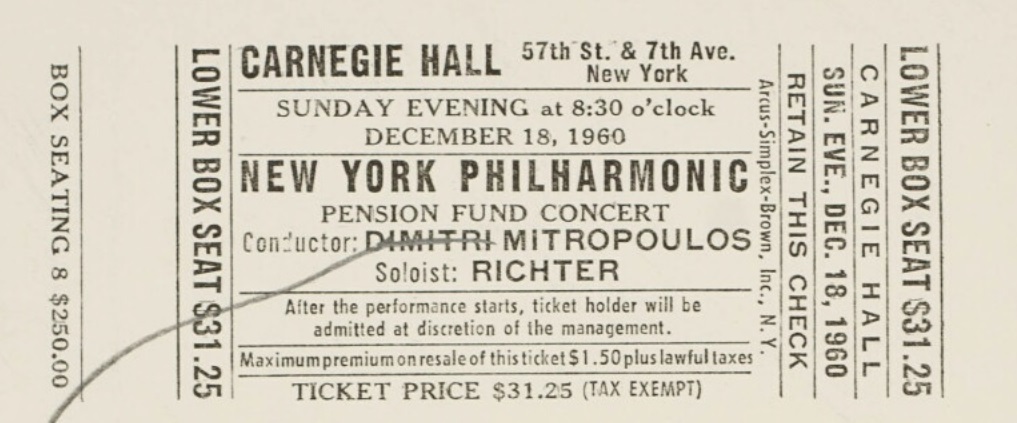

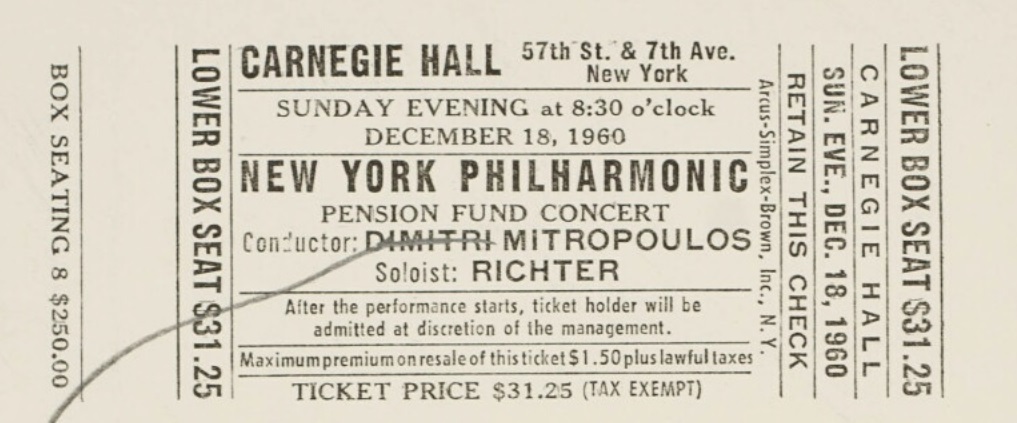

Mitropoulos avait également des engagements à New-York avec le New-York Philharmonic et le Metropolitan Opera**. Il s’agissait tout d’abord d’un prestigieux concert supplémentaire qui avait été décidé probablement début octobre et pour lequel un accord avait été finalisé le 18 octobre: le « Pension Fund Concert » du 18 décembre avec une rencontre qui promettait d’être exceptionnelle avec le pianiste Sviatoslav Richter (Beethoven Concerto n°1 et Brahms Concerto n°2). Deux répétitions avaient été prévues le 14 et le 17 en tenant compte des engagements que Mitropoulos avait avec le Metropolitan Opera.

Le 28 octobre, le concert a été mis en location par correspondance. L’administration a été submergée par les demandes de billets, et plus de 2000 chèques ont dû être retournés aux souscripteurs. Le concert a finalement été dirigé par Bernstein et Richter a joué Liszt (Concerto n°2) et Tchaïkovski (Concerto n°1).

Pour la saison 1960-1961, Dimitri Mitropoulos avait des engagements pour quatre semaines de concerts successives avec le NYPO:

I – 29 et 30 décembre 1960 1er janvier 1961: Mahler Symphonie n°3 avec Martha Lipton. Le chef de chœur Hugh Ross propose de faire répéter ensemble un chœur féminin (27) du Berkshire Music Center (plutôt que la Schola Cantorum de New-York) et un chœur d’enfants (25) de la High School of Music and Art.

II – 5, 6 ,7 et 8 janvier 1961: Bach-Schoenberg Prélude et Fugue en mi mineur; Katchaturian Concerto pour violoncelle avec Rohan de Saram; Scriabine Prométhée (Poème du Feu) Op.60.

III – 12, 13, 14 et 15 janvier 1961: Mendelssohn Symphonie n°3; Krenek Medea avec Blanche Thebom; Gould Dialogues pour piano et orchestre à cordes avec Morton Gould; Skalkottas Danses Grecques.

IV – 19, 20, 21 et 22 janvier 1961: Beethoven Symphonie n°2; Berg 3 Pièces pour orchestre Op.6; Prokofiev Concerto pour piano n°3 Zadel Skolovsky; Berlioz Rob Roy, Ouverture.

Ces concerts, reprogrammés dans l’urgence, ont été assurés avec des programmes presque entièrement différents, par Stanislav Skrowaczewski pour les deux premiers et Paul Paray pour les deux suivants.

La Troisième de Mahler a été donnée plus tard, les 30 et 31 mars, et les 1 et 2 avril 1961 sous la direction de Leonard Bernstein, à la mémoire de Dimitri Mitropoulos.

Trois ans après son départ de la direction du NYPO, l’attitude de l »administration de l’orchestre à son égard avait changé. Les succès rencontrés au Met ainsi qu’en Europe (Festival de Salzburg, Wiener Staatsoper, WDR Köln) y ont vraisemblablement été pour beaucoup. Un autre indice de ce relatif rapprochement se trouve dans le fait que, pour ses concerts de l’été et de l’automne 1960, Mitropoulos avait emprunté au NYPO la partition orchestrale et le matériel d’orchestre de « La Mer » de Debussy. Après son décès, eut lieu un échange de courrier inquiet entre Joan Bonime (NYPO) et Karl O. Hoch (WDR) pour récupérer ces précieux documents, ce qui eut lieu effectivement dans les semaines qui suivirent. A noter que Mitropoulos, qui dirigeait par cœur, avait laissé la partition dans son appartement de New-York, et n’avait emmené en Europe que le matériel d’orchestre!

Les enregistrements radiophoniques qui nous restent de cette période (les deux concerts de Salzburg, la représentation de la Forza del Destino du 23 septembre au Wiener Staatsoper, la Neuvième de Mahler avec le WPO le 2 octobre et les deux concerts avec l’Orchestre de la WDR Köln avec la magnifique prestation de Lucretia West dans Mahler) sont d’inestimables documents.

* Bruno Zirato était jusqu’en 1959 l’Administrateur Général du New-York Philharmonic. Cette lettre a été publiée dans un article commémoratif signé par Bruno Zirato, inclus dans le programme du Metropolitan Opera du 5 décembre 1960. Mitropoulos avait des engagements au « Met » pour le mois de décembre, mais aucune documentation n’est disponible à ce sujet.

** Le 2 novembre, avant la représentation de Boris Godounov au « Met », l’orchestre joue sans chef la Danse des Esprits Heureux de l’ « Orfeo ed Euridice » de Gluck et Rudolf Bing s’adresse au public en ces termes: « Une autre grande tragédie a frappé le Metropolitan Opera et en fait le monde musical. Notre bien-aimé Dimitri Mitropoulos est décédé ce matin à Milan. Vous l’aimiez tous et vous savez qu’il était un des grands musiciens et un des grands chef d’orchestre de notre temps, ainsi qu’un extraordinaire être humain. Sa perte est personnellement ressentie par chacun au Metropolitan – en fait tous les membres de cet orchestre étaient ses amis. Bien sûr le Metropolitan Opera va continuer et d’autres grands chefs pourraient aller et venir, mais il y aura toujours dans nos cœurs une place spéciale pour Dimitri Mitropoulos «

__________________

This was Dimitri Mitropoulos’ last concert. In spite of his health condition, he drove himself hard during the summer and the autumn of 1960 with a heavy schedule, reconstructed here for the first time.

At the 1960 Salzburg Festival, he gives two triumphal concerts (Mendelssohn Symphony n°3, Schoenberg Variations Op.31 and Debussy La Mer on August 21, and Mahler Symphony n°8 on August 28). Then, he conducts at the Wiener Staatsoper six performances (September 23, 27 and 30 and October 7, 12 and 15) of Verdi’s « La Forza del Destino » de Verdi considered by the Austrian press as a stroke of genius, interleaved with two programs at the Musikvereinsaal with the Wiener Philharmoniker on the one hand on October 1 and 2 (Mahler Symphony n°9), and on the other hand on October 8 and 9 (Schumann Symphony n°2, Th. Berger Jahreszeiten and Debussy La Mer). These two programs are performed again during a short tour on October 10 in Graz for the first one, and on October 11 in Linz for the second.

Thereafter, he travels to Cologne for a series of four concerts with the WDR Sinfonie Orchester (Kölner Rundfunk Sinfonie Orchester).

The first of them, on October 24, has the same program as the BPO August 21 Salzburg concert, and the second, on October 31, is then dedicated to the Mahler’s Third. During the October 31 concert, he succeeds in overcoming a stroke during the first movement, but however refuses the urging advices against resuming the concert after the intermission following the first movament, only accepting to conduct seated. After the end of the performance, in spite of his high state of exhaustion, he takes the night train to Milan where he is to conduct that same Third Symphony with La Scala Orchestra on November 7.

On the evening of November 1st, he writes in his Milan hotel room a short letter to Bruno Zirato’s wife*, Nina, which he mails the next morning while going to his rehearsal with the Scala Orchestra: « Here I am in Milano. I am miserable, dead tired, and I am worried over the state of my health. The climate in Cologne did me no good…. I was always short of breath. Dear friends, please pray that I will be able to return to New York, and not be forced to enter a hospital here. Your unhappy Dimitri ».

Mitropoulos’ death during the November 2 rehearsal has been told in Willam R. Trotter’s book « Priest of Music The Life of Dimitri Mitropoulos« .

Karl O. Hoch (WDR – Leiter der Hauptabteilung Musik) announces in his broadcast tribute that the conducter has accepted to become Music Director of the Kölner Rundfunk Sinfonie Orchester. The programs of the other two Cologne concerts on November 14 and 21 are not known.

Mitropoulos was also to perform in New-York with the New-York Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera**. Firstly, it was a prestigious supplementary concert that was probably decided at the beginning of October and for which an agreement was finalized on October 18: the December 18 « Pension Fund Concert » with an exceptionally promising meeting with pianist Sviatoslav Richter (Beethoven Concerto n°1 and Brahms Concerto n°2). Two rehearsals were set on December 14 and 17 to take care of Mitropoulos’ schedule with the Metropolitan Opera.

On October 28, a mail order was launched. The administration was overflooded with orders for tickets and more than 2,000 cheques had to be returned to subscribers. The rescheduled concert was conducted by Bernstein and Richter played Liszt (Concerto n°2) and Tchaïkovski (Concerto n°1).

For the 1960-1961 season, Dimitri Mitropoulos was to perform during four successive weeks with the NYPO:

I – December 29 and 30, 1960 and January 1st, 1961: Mahler Symphony n°3 with Martha Lipton. Choir director Hugh Ross suggested to make joint rehearsals with a women choir (27) from the Berkshire Music Center (rather than from the Schola Cantorum of New York) and a children choir (25) of the High School of Music and Art.

II – January 5, 6 ,7 and 8, 1961: Bach-Schoenberg Prelude and Fugue in E flat; Katchaturian Cello Concerto with Rohan de Saram; Scriabin Prometheus (Poem of Fire) Op.60.

III – January 12, 13, 14 and 15, 1961: Mendelssohn Symphony n°3; Krenek Medea with Blanche Thebom; Gould Dialogues for piano and string orchestra with Morton Gould; Skalkottas Greek Dances.

IV – January 19, 20, 21 and 22, 1961: Beethoven Symphony n°2; Berg 3 Orchestra Pieces Op.6; Prokofiev Piano Concerto n°3 Zadel Skolovsky; Berlioz Rob Roy, Overture.

These concerts, hastily rescheduled, were given with almost entirely different programs by Stanislav Skrowaczewski for the first two and Paul Paray for the next two.

The Mahler Third was performed later on March 30 and 31 and on April 1 and 2, 1961 under the direction of Leonard Bernstein, in Memory of Dimitri Mitropoulos.

Three year after he left the NYPO as its Music director, the administration of the orchestra saw him differently. His success at the Met as well as in Europe (Salzburg Festival, Wiener Staatsoper, WDR Köln) were most certainly very instrumental. Another sign of this better relationship may be found in the fact that, for his 1960 summer and autumn concerts, Mitropoulos borrowed to the NYPO the orchestral score and the orchestral parts of « La Mer » by Debussy. After his death, an anxious exchange of letters took place between Joan Bonime (NYPO) and Karl O. Hoch (WDR) to get back these precious documents, which successfully happened during the next weeks. It is worth noting that Mitropoulos, who conducted by heart, left the orchestral score in his New York flat, and only brought with him to Europe the orchestral parts!

The broadcast recordings that have survived from that period (both Salzburg concerts, the Wiener Staatsoper performance of La Forza del Destino on September 23, the Mahler Ninth with the WPO on October 2 and both WDR Köln concerts, including Lucretia West beautifully singing Mahler) are as many historical documents.

* Bruno Zirato was until 1959 the General Manager of the New-York Philharmonic. This letter was published as part of a tribute signed by Bruno Zirato, in the December 5, 1960 program of the Metropolitan Opera. Mitropoulos was to conduct at the « Met » during the month of December, but it is not documented.

** On November 2, before the performance of Boris Godounov at the « Met », the orchestra plays without a conductor the Dance of the Blessed Spirits from « Orfeo ed Euridice » by Gluck and Rudolf Bing talks to the public with these words: « Another great tragedy has befallen the Metropolitan Opera and indeed the musical world. Our beloved Dimitri Mitropoulos died this morning in Milan. You all loved him, and you know he was one of the great musicians and great conductors of our time, and also an outstanding human being. His loss is felt personally by everyone at the Metropolitan – indeed all the members of this orchestra were his friends. Naturally the Metropolitan Opera will go on and other great conductors may come and go, but there will always be a very special place in our hearts for Dimitri Mitropoulos.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

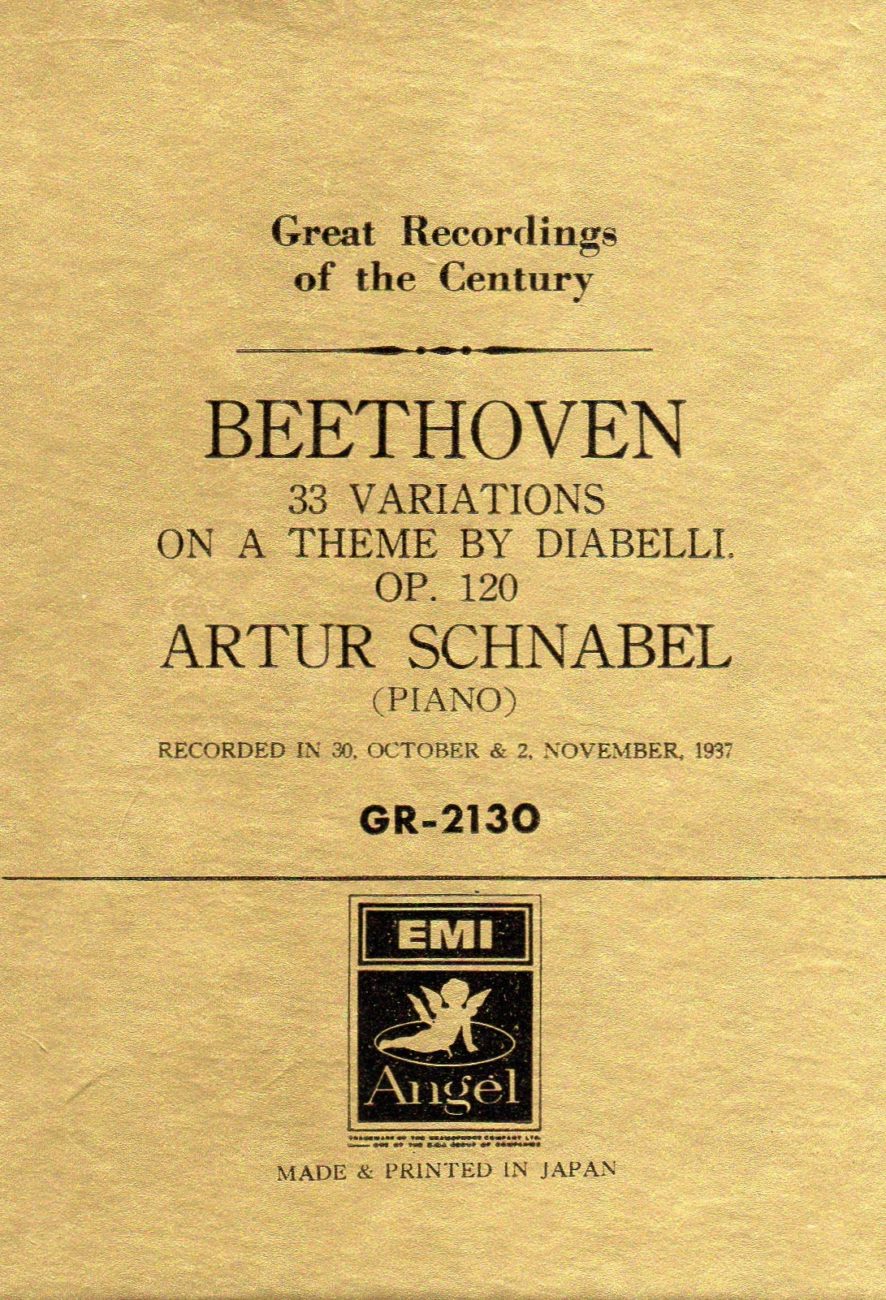

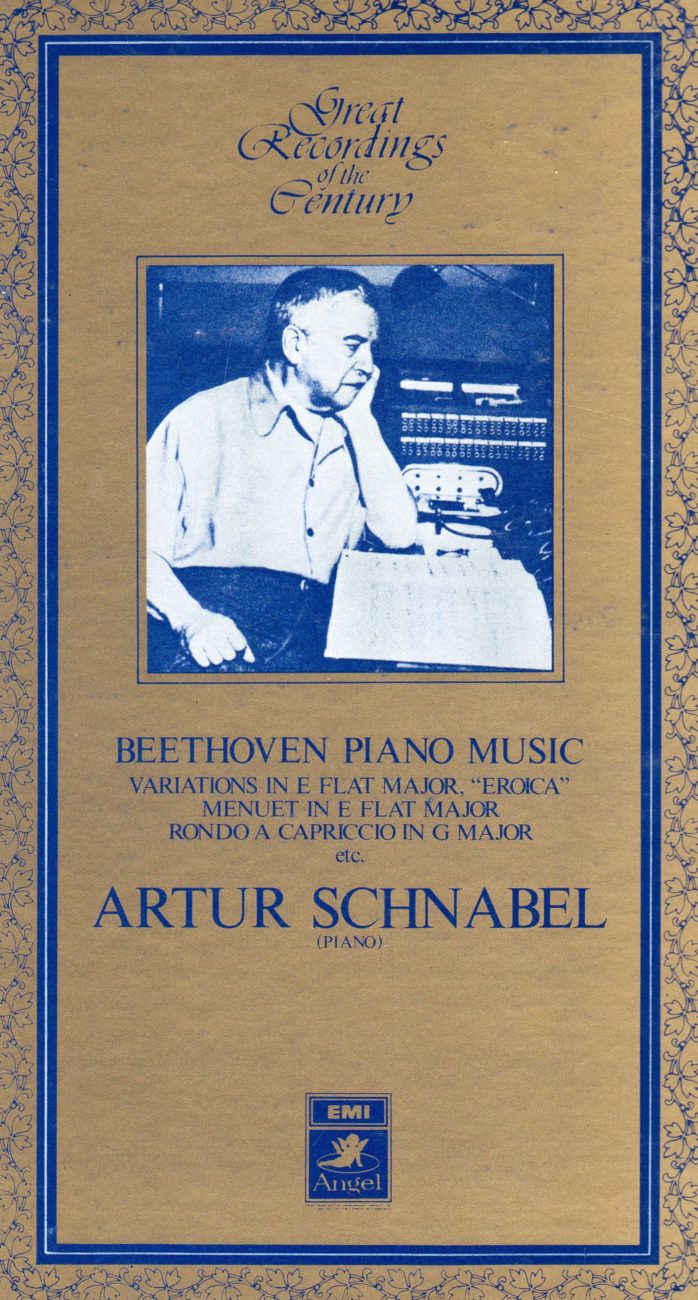

Artur Schnabel, piano Bechstein – London Abbey Road Studio n°3

Variations « Diabelli » Op.120 October 30 & November 2, 1937 (Bechstein n°560)

Variations « Eroïca » Op.35 – November, 9 1938

Engineer: Edward Fowler

Les deux microsillons EMI-Toshiba qui ont servi à cette ré-édition proviennent de reports effectués par Anthony Griffith. Réalisés à partir de pressages vinyles des matrices 78t. d’origine, ils présentent la particularité d’être peu ou pas filtrés et ainsi de nous offrir toute la palette sonore du pianiste, car la technique d’Artur Schnabel, souvent critiquée par ailleurs à cause de ses fausses notes, comportait une gamme très étendue de nuances et de gradations de toucher, de la douceur à la puissance.

La richesse d’écriture de ces variations de Beethoven permet fort heureusement à Schnabel de déployer tout l’éventail de ses qualités pianistiques.

Au cours d’une série de conférences données en 1945 à l’Université de Chicago, Schnabel a eu l’occasion, en réponse à des questions posées posées par les étudiants, d’expliquer quelle avait été sa conception du choix des pianos et de la production du son avant qu’il ne se décide à passer du Bechstein au Steinway à son arrivée aux États-Unis en 1939:

« Je dirais que la qualité qui distingue le piano de tous les autres instruments, est sa neutralité. Sur un piano, un son unique ne peut être beau; c’est la combinaison et la proportion des sons qui apporte la beauté.

Il est nécessaire de produire au moins deux ou trois sons pour donner une impression de sensualité ou pour donner à l’oreille une sensation de musique, alors que presque tous les autres instruments (sauf les instruments à percussion) ou la voix peuvent vous donner un plaisir des sens même avec un seul son. Autour de 1910, on trouvait très ‘moderne’ de dire que le piano était un instrument à percussion et que vous pouviez tout jouer staccato. Stravinsky a beaucoup fait pour la promotion de ces idées de même que de nombreux professeurs de piano, et il y avait même un livre sur ce sujet.

Une fois, un musicien m’a dit – je croyais qu’il plaisantait- que frapper le clavier avec le bout d’un parapluie ou avec le doigt ne faisait pas la moindre différence quant à la sonorité produite. C’était aussi imprimé dans ce livre – et ce n’était pas non plus une plaisanterie. Bien sûr, ça n’a aucun sens, car quiconque veut faire de la musique sait très bien tout ce qu’il peut faire avec les doigts sur le piano.

Il peut produire toutes sortes de sons: pas seulement plus ou moins forts, ou plus ou moins longs, mais aussi différentes qualités. Sur un piano, il est possible d’imiter, par exemple, le son d’un hautbois, d’un violoncelle ou d’un cor. Mais il n’est pas possible d’imiter le son d’un hautbois sur une flûte, ou d’une clarinette sur un violon; ces autres instruments conservent toujours leurs caractéristiques propres. C’est pour ça que je dis que la particularité du piano est, dans son essence, d’être le plus neutre des instruments.

Le piano Bechstein satisfaisait mieux à cette exigence de neutralité que n’importe quel autre piano que j’ai connu. Vous pouviez pratiquement tout faire sur ce piano. Le Steinway – ou plutôt le Steinway d’il y a vingt ans, car il a pas mal changé depuis – était un piano qui voulait toujours montrer quelque chose. Vous voyez, il avait beaucoup trop de personnalité propre.

Au début, quand je voulais produire quelque chose comme, disons, la voix d’un oiseau sur un Steinway, le piano sonnait toujours pour moi comme la voix d’un ténor au lieu d’un oiseau. Pendant de nombreuses années, j’ai eu le sentiment que le piano Steinway ne m’aimait pas. Une idée absurde, mais j’avais ce sentiment. Le piano Bechstein me permettait de produire des effets qui n’étaient pas possibles sur un Steinway. Le son du Steinway vibrait beaucoup plus: il a un double actionnement. Quand vous pressez très légèrement et lentement la touche d’un Steinway, elle s’arrête avant le bas, et elle a besoin d’une certaine pression, d’une seconde pression pour achever sa course vers le bas. Maintenant, j’y suis tellement habitué que cela ne m’irrite plus du tout. Au début, cependant, cela me gênait énormément: en effet, pour produire un fortissimo, vous pouvez jouer légèrement, mais si vous voulez jouer pianissimo, vous avez besoin d’utiliser beaucoup de poids sinon la touche ne descend pas. Cela semble assurément pervers. »

Both EMI-Toshiba LPs used for this re-issue come from transfers made by Anthony Griffith. Dubbed from vinyl pressings of the 78rpm metal parts, they have the particularity of having been unfiltered, or very little, and thus to offer all the pianist’s sound palette, since Artur Schnabel’s technique, otherwise often criticized because of his wrong notes, was comprised of a very extended range of nuances and touch, from softness to power.

The richness of writing of these variations by Beethoven happily allows Schnabel to show the whole spectrum of his pianistic qualities.

During a series of conferences given in 1945 at the University of Chicago, Schnabel, answering questions asked by students, had the opportunity of explaining what had been his views on the choice of pianos and on the production of sound before he decided to switch from Bechstein to Steinway when he arrived in the U-S in 1939:

« I would say that the quality which distinguishes the piano from all other instruments, is its neutrality. On a piano a single tone cannot be beautiful; it is the combination and proportion of tones which bring beauty.

You are forced to produce at least two or three tones in order to create a sensuous impression or to give a sensation of music to the ear, while almost all other instruments (except percussion instruments) or the voice can give you a sensuous pleasure even from a single tone. Around 1910 it was considered very ‘modern’ to say that the piano is a percussion instrument and that you could play everything staccato. Stravinsky did much towards promoting these ideas along with many piano teachers, and there was a book on the subject.

Once I was told by a musician—I hope he was joking—that it does not make the slightest difference for the sonority whether you strike or hit the keyboard with the tip of an umbrella or with a finger. That was also printed in that book—and not as a joke. Of course it is sheer nonsense, for everybody who wants music knows very well all that he can do with the fingers on the piano.

He can produce all kinds of tones: not only louder or softer, shorter or longer tones, but also different qualities. It is possible on a piano to imitate, for instance, the sound of an oboe, a ‘cello’, a French horn. But it is not possible to imitate the sound of an oboe on a flute, or a clarinet on a violin; these other instruments always retain their own characteristics. That is why I said that the distinction of the piano is in its being the most neutral instrument.

The Bechstein piano fulfilled this demand for neutrality better than any other piano I have known. You could do almost anything on that piano. The Steinway—or rather the Steinway of twenty years ago, for it has changed somewhat since that time—was a piano which always wanted to show something. You see, it had much too much of a personality of its own.

At first, when I wanted to produce something like, let me say, the voice of a bird on a Steinway, the piano always sounded to me like the voice of a tenor instead of a bird. For many years, I had the feeling that the Steinway piano did not like me. An absurd idea, but I had that feeling. The Bechstein piano enabled me to show effects not possible on a Steinway. The tone of the Steinway vibrated much more: it has a different action. When you push a Steinway key very lightly and slowly down, it will stop before it has reached the bottom and requires a certain pressure, a second pressure to go down all the way. This is the »double action ». By now I am so used to it that it hardly irritates me any more. At first, however, it disturbed me greatly: for in order to produce a « fortissimo » you can play lightly, but whenever you want to play « pianissimo » you have to use a great deal of weight as otherwise the key would not go down. It certainly seems perverse.«

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

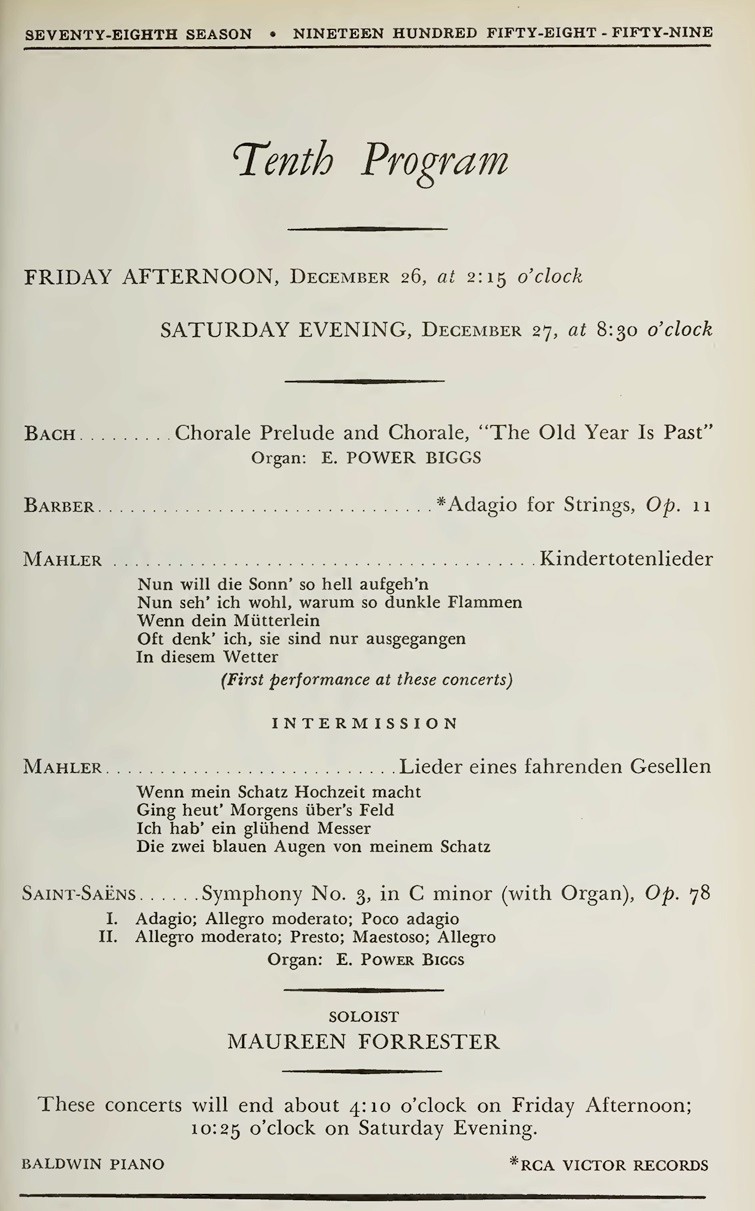

Maureen Forrester, contralto

Boston Symphony Orchestra Charles Munch

Boston Symphony Hall – December 27 1958

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

Les enregistrements de Maureen Forrester sont des joyaux de la discographie mahlérienne. On ne ne connait pas la raison du choix de Charles Munch pour diriger ces œuvres, car c’est quasiment la seule fois où, avec le BSO, il a abordé ce compositeur. Le fait est que le disque commercial qui en est résulté est réussi, tant du point de vue du chant que de la direction.

C’est la première fois que les Kindertotenlieder sont donnés par le BSO dans le cadre des concerts d’abonnements à Boston. Auparavant, Marcia Davenport les avait chantés en 1944 avec des membres du BSO sous la direction de Bernard Zighera, et en 1949 le Festival de Tanglewood les avait programmés avec Helen Spaet sous la direction d’Howard Shanet.

Mahler avait été précédemment beaucoup plus joué à Boston qu’on ne le pense:

Symphonie n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphonie n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphonie n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphonie n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphonie n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphonie n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky n’était pas du tout répertorié comme chef mahlérien, et après lui, la direction des œuvres de Mahler a été, au cours des années cinquante, surtout confiée à Richard Burgin, le « concert-master » de l’orchestre (notamment les Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen en 1952), plutôt qu’à des chefs invités.

Le concert du 27 décembre 1958 est la plus ancienne archive conservée en stéréo du BSO en public. L’interprétation en concert se caractérise par une très grande écoute réciproque entre la soliste et les membres de l’orchestre que le chef laisse heureusement se développer. Rappelons que Munch a été pendant plusieurs années un des violons solo du Gewandhausorchester de Leipzig, qui était surtout l’orchestre de l’Opéra, et qu’en cette qualité, il avait acquis une grande expérience de l’accompagnement des solistes.

Le choix du reste du programme n’était pas particulièrement heureux. Pour terminer, Munch s’était en effet livré dans la Symphonie n°3 de Saint-Saëns à une des prestations spectaculaires qu’il affectionnait, ici relativement bien mise en place, et qui lui ont valu à la fois beaucoup de succès et beaucoup de critiques.

Maureen Forrester’s recordings are jewels of the Mahler discography. It is not known why Charles Munch was chosen to conduct these works, since it is the only time he conducted them, and almost the only time he conducted this composer with the BSO. Anyway, the commercial recording that came out of it was successful, for the singing as well as the conducting.

It was the first time that the Kindertotenlieder were performed at the BSO abonnement concerts. Earlier, Marcia Davenport sang them in 1944 with members of the BSO conducted by Bernard Zighera, and in 1949 they were performed at the Tanglewood Festival by Helen Spaet and conducted by Howard Shanet.

In Boston, Mahler was previously performed more than one thinks:

Symphony n°1: Monteux (1923), Mitropoulos (1936), Burgin (1942, 1943, 1955)

Symphony n°2: Muck (1918), Bernstein (1948, 1949, 1953)

Symphony n°4: Burgin (1945, 1954, 1957), Walter (1947)

Symphony n°5: Gericke (1906); Muck (1913-1915), Koussevitzky (1937, 1938, 1940), Burgin (1948, 1951)

Symphony n°7: Koussevitzky (1948)

Symphony n°9: Koussevitzky (1931-1933, 1936, 1941), Burgin (1952)

Das Lied von der Erde: Koussevitzky (1928, 1930, 1936,1937, 1949), Burgin (1943, 1950)

Koussevitzky did not have a reputation as a Mahler conductor, and after him, during the 50’s his works were mostly conducted by Richard Burgin, the orchestra « concert-master » (a.o. the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen in 1952), rather than by invited conductors.

The December 27, 1958 concert is the oldest stereo archive from the BSO live. The public performance shows a quite great mutual hearing between the soloist and the orchestra members which the conductor lets develop freely. For several years, Munch was one of the « Konzertmeister » of the Leipzig Gewandhausorchester, mainly performing at the Opera, and he then acquired a great experience with the accompaniment of singers.

The remainder of the program was not particularly well chosen. To end the concert, Munch delivered in Saint-Saëns’ Symphony n°3 one of the spectacular performances he was fond of, rather well in place, of a type that owned him plenty of successes as well as criticisms.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.