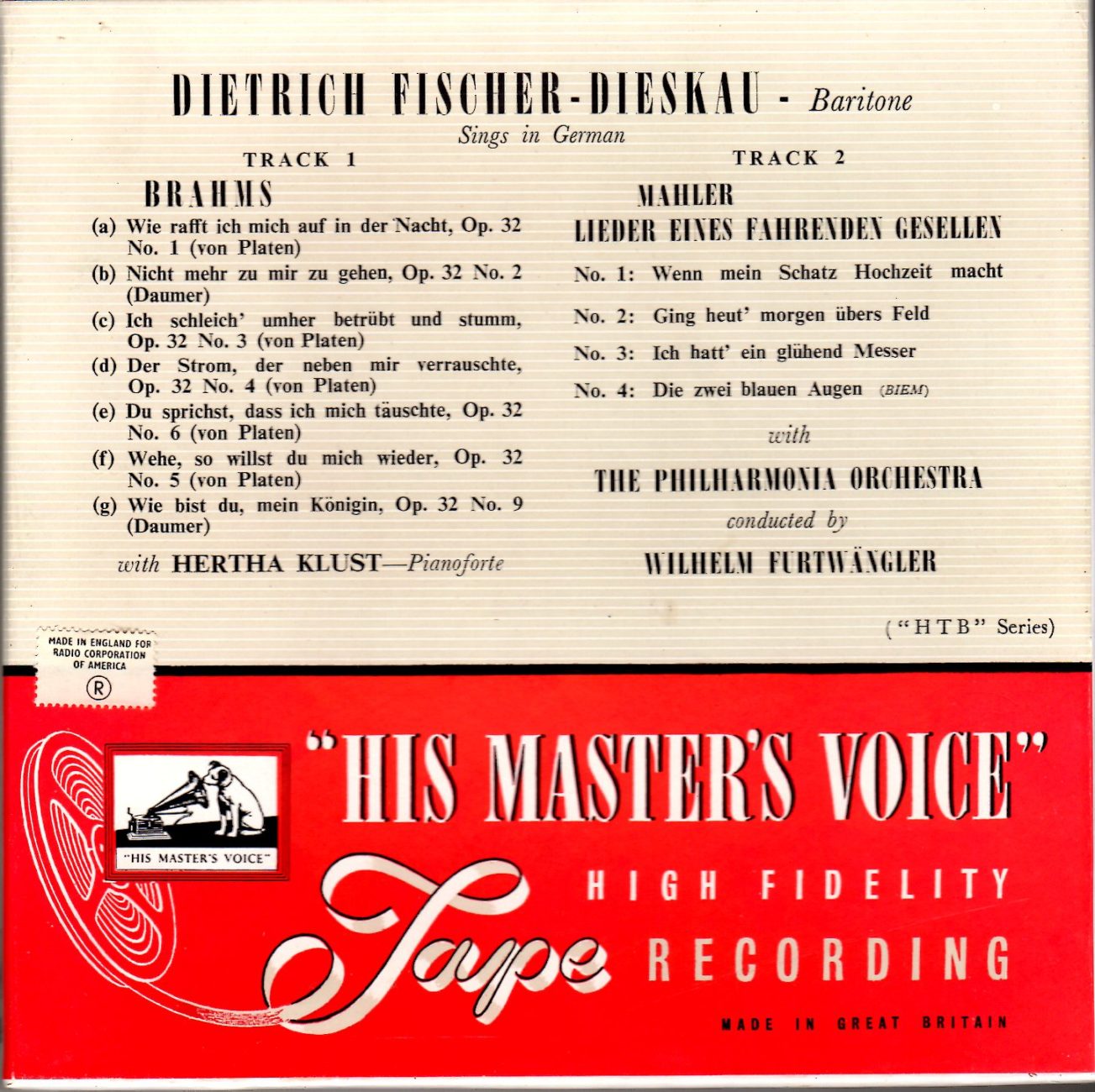

Brahms Lieder und Gesänge Op.32 n° 1-6 & 9 Hertha Klust piano

Berlin 25 mai 1955 – Prod: Fritz Ganss Eng: Horst Lindner

Mahler Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen – Philharmonia Orchestra Wilhelm Furtwängler – London Kingsway Hall 24 & 25 juin 1952

Prod: Lawrence Collingwood Eng: Douglas Larter

Bande HMV 19cm/s 2 pistes HTB 409

En 1956, HMV a publié ces enregistrements en microsillon (ALP 1270), mais aussi sous forme de bande magnétique HTB 409. Le couplage de ces deux œuvres est inhabituel, et ce d’autant plus que Fischer-Dieskau a enregistré en juin 1955 les Kindertotenlieder de Mahler avec le BPO sous la direction de Rudolf Kempe. Essayons d’en décrypter les raisons:

Les Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen ont été enregistrés par Fischer-Dieskau et Furtwängler les 24 et 25 juin 1952 en profitant du temps d’enregistrement disponible après les séances consacrées à l’intégrale de Tristan und Isolde de Wagner.

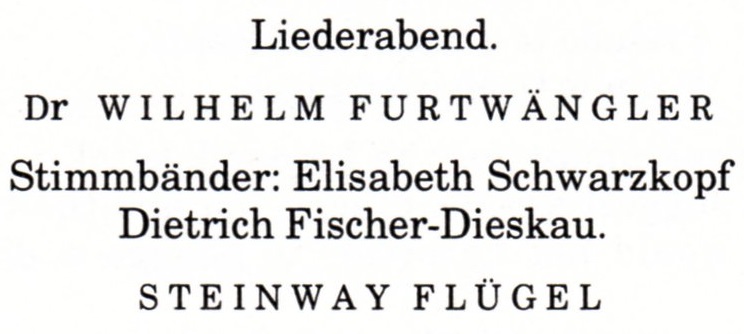

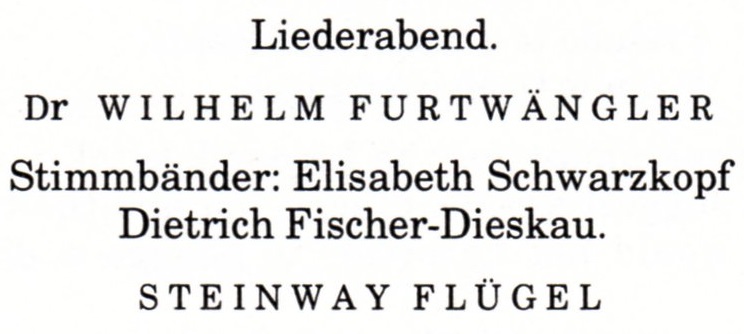

Le 29 novembre 1953, Furtwängler écrit à Walter Legge en évoquant l’enregistrement du Monologue d’Amfortas en projet avec Fischer-Dieskau et le Philharmonia lors de sa venue à Londres en mars 1954: « J’imagine que les Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen enregistrés avec Fischer-Dieskau n’ont toujours pas été publiés. Comme je fais dans les prochains jours les Kindertotenlieder avec Fischer-Dieskau à Berlin, ce serait semble-t-il une bonne idée de les enregistrer à la place du Monologue d’Amfortas si on dispose d’assez de temps ». Le 3 décembre, Legge confirme ce changement. De plus, entre les deux concerts de Furtwängler prévus avec le Philharmonia au Royal Festival Hall les 5 et 12 mars 1954, un étonnant Récital de Lieder de Schumann avait été programmé le 7 mars dans cette même salle avec Fischer-Dieskau et Schwarzkopf, Furtwängler étant au piano. Legge propose le programme suivant: Dichterliebe, Frauenliebe und Leben et 15 Duos.

Le 12 janvier 1954, Furtwängler écrit à Legge depuis le sanatorium d’Ebersteinburg (Baden-Baden) où il doit séjourner pour se remettre des effets de ses traitements aux antibiotiques américains qu’il avait pris le mois précédent. Il a du annuler une tournée avec le BPO et une autre (au Portugal) avec le WPO, ainsi qu’une série d’autres concerts. Il annonce en outre qu’il ne pourra assurer à Londres que le concert du 12 mars. Il demande donc d’annuler le concert du 5 mars et le Récital du 7 mars. Le 18 janvier, Legge lui répond en exprimant ses regrets. Le 2 février, Furtwängler lui confirme qu’il ne dirigera que le concert du 12 mars et en confirme le programme. Le 7 février, Furtwängler écrit à Legge pour lui faire savoir que ses médecins l’autorisent finalement à reprendre ses activités le 1er mars et qu’il a programmé une série d’enregistrements avec le WPO (N.B. en fait du 28 février au 8 mars). Il n’est plus question d’enregistrer les Kindertotenlieder. Il n’en sera également pas fait état dans les échanges ultérieurs entre le chef et Legge.

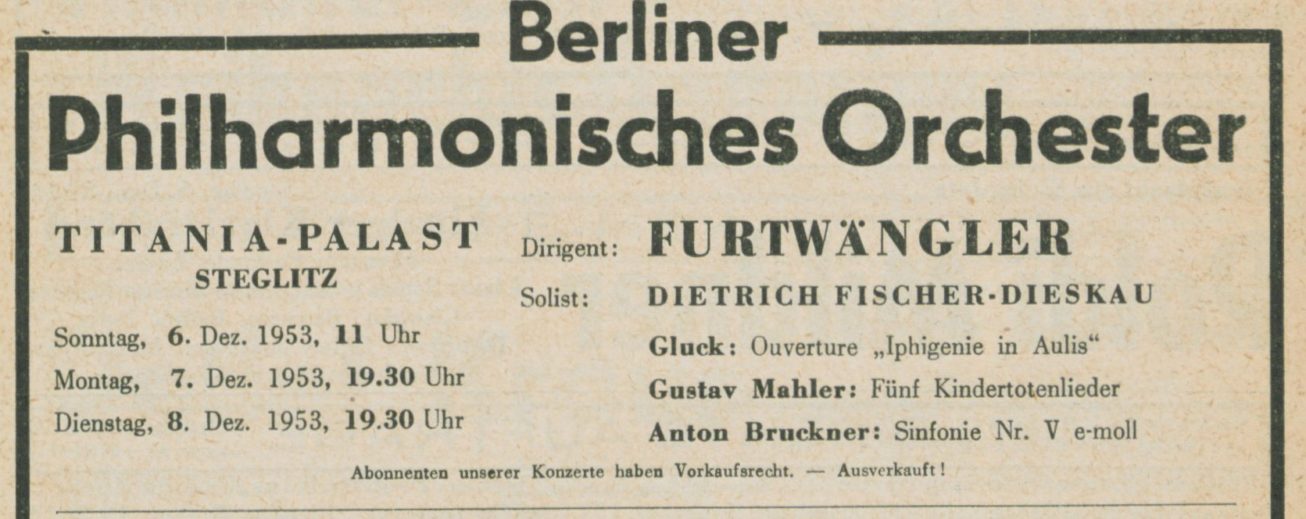

Quant à Fischer-Dieskau, il recherchera activement, mais en vain, un enregistrement des Kindertotenlieder provenant des concerts berlinois de décembre 1953.

Dans ses mémoires, il laisse entendre qu’à l’époque il n’est pas satisfait de l’enregistrement qu’il en a fait avec Rudolf Kempe et le BPO en raison du manque d’entente entre l’orchestre et le chef. Ce sont probablement les raisons du choix du couplage Brahms/Mahler, grâce auquel la subtilité du piano d’Hertha Klust (1907-1970), que d’ailleurs Furtwängler appréciait beaucoup, mais dont la carrière fut semble-t-il abrégée par des problèmes auditifs, répondait à celle de la direction de Furtwängler.

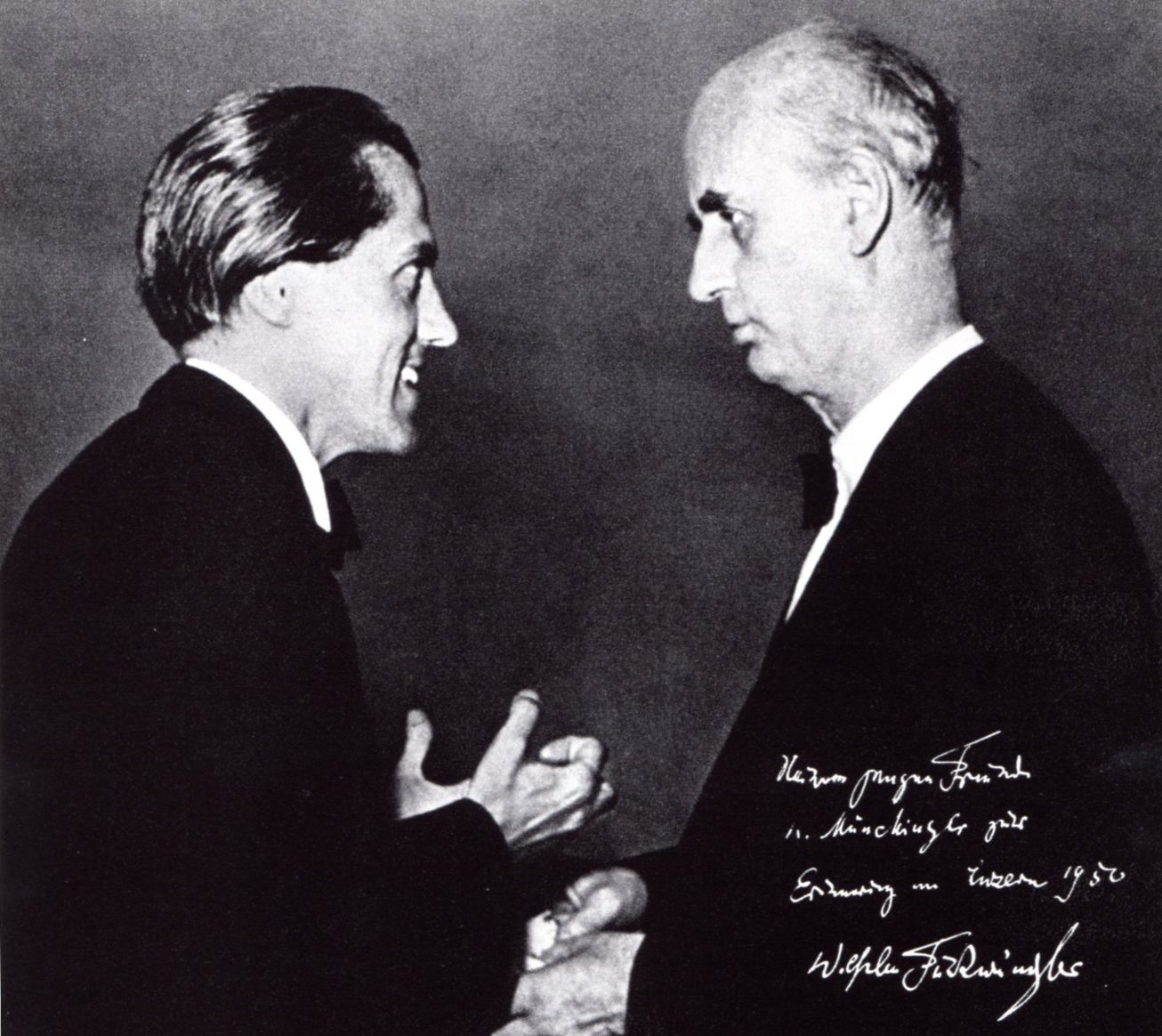

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau & Wilhelm Furtwängler – Titania Palast Décembre 1953

______________

In 1956, HMV published these recordings as a LP (ALP 1270), but also on a reel-to-reel magnetic tape HTB 409. The coupling of these two works is unusual, al the more so, since Fischer-Dieskau recorded in June 1955 Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with the BPO conducted by Rudolf Kempe. Let’s attempt an explanation:

The Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen were recorded by Fischer-Dieskau and Furtwängler on June 24 and 25, 1952 during available recording time further to the sessions devoted to the complete recording of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

On November 29, 1953, Furtwängler writes to Walter Legge and mentions the project recording of the Amfortasmonolog with Fischer-Dieskau and the Philharmonia during his stay in London in March 1954: « I gather that the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen with Fischer-Dieskau, which we recorded, have still not been released. As I am doing the Kindertotenlieder with Fischer-Dieskau in Berlin in the next few days, it would seem to be a good idea to record this as well – instead of the Amfortasmonolog – if there is time ». On December 3, Legge confirms the change. Moreover, between both Furtwängler’s concerts arranged with the Philharmonia at the Royal Festival Hall on March 5 and 12, 1954, an astonishing Recital of Lieder by Schumann had been scheduled on March 7 in the same venue with Fischer-Dieskau and Schwarzkopf, Furtwängler being the pianist. Legge suggests the following program: Dichterliebe, Frauenliebe und Leben and 15 Duets.

On January 12, 1954, Furtwängler writes to Legge from the Ebersteinburg sanatorium (Baden-Baden) were he has to stay to undergo a course of treatment which became necessary as a consequence of American antibiotics which were given to him the previous month. He had to cancel a tour with the BPO and another one (in Portugal) with the WPO, as well as a series of other concerts. He also mentions he will be able to conduct only the second London concert on March 12. As a consequence, he requests the cancellation of the March 5 concert as well as of the Recital of March 7. On January 18, Legge answers and expresses his regrets. On February 2, Furtwängler confirms he will conduct only the March 12 concert and also confirms the program. On February 7, Furtwängler writes to Legge to inform him that his doctors can discharge him as early as March 1st and that he has arranged with the WPO to do some recordings during that period (N.B. in fact between February 28 and March 8). It is no longer contemplated to record the Kindertotenlieder. Nor will this recording be further discussed in the next letters between the conductor and Legge.

As to Fischer-Dieskau, his active searches to find a recording of the Kindertotenlieder from the December 1953 Berlin concerts remained fruitless.

In his memoirs, the singer suggests that he was then not satisfied with the recording of this work he made with Rudolf Kempe and the BPO, because of the lack of understanding between the orchestra and the conductor. These are probably the reasons for the choice of the Brahms/Mahler coupling, thanks to which the subtility of the piano of Hertha Klust (1907-1970), whom by the way Furtwängler liked very much, but whose career was most probably shortened by hearing problems, mirrored that of Furtwängler’s conducting.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

Franz Schubert Symphonie n°6 D.589: 22-25 février 1965

Prod: Ray Minshull Eng: Gordon Parry

(Bande 19cm/s 4 pistes London LCL 80180)

Symphonie n°8 D.759: 13-17 mars 1959

Prod: Erik Smith Eng: James Brown

(Bande 19cm/s 4 pistes London LCL 80038)

Wien Sofiensaal

___________

Voici enfin le Volume III avec les symphonies n°6 & 8 « Inachevée » de Franz Schubert enregistrées à la Sofiensaal de Vienne par les Wiener Philharmoniker sous la direction de Karl Münchinger. Pour cette dernière œuvre, Münchinger pousse très loin les contrastes dynamiques, à l’instar de Wilhelm Furtwängler. Ceci rappelle que, si Münchinger a étudié à Leipzig la direction d’orchestre avec Hermann Abendroth, son modèle était Wilhelm Furtwängler. Il n’est donc guère étonnant qu’il y ait des similitudes entre son interprétation et celle de Furtwängler.

To end with, here is Volume III with Franz Schubert’s Symphonies n°6 & 8 « Unfinished » recorded in Vienna at the Sofiensaal by the Wiener Philharmoniker conducted by Karl Münchinger. In the latter work, it is clear that Münchinger pushes very far the contrasts in dynamics, in the style of Wilhelm Furtwängler. This reminds us that, although Münchinger studied conducting in Leipzig with Hermann Abendroth, his model was Wilhelm Furtwängler. Little wonder then that there are similarities between his performance and Furtwängler’s.

Karl Münchinger & Wilhelm Furtwängler (Luzern 1950)

___________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

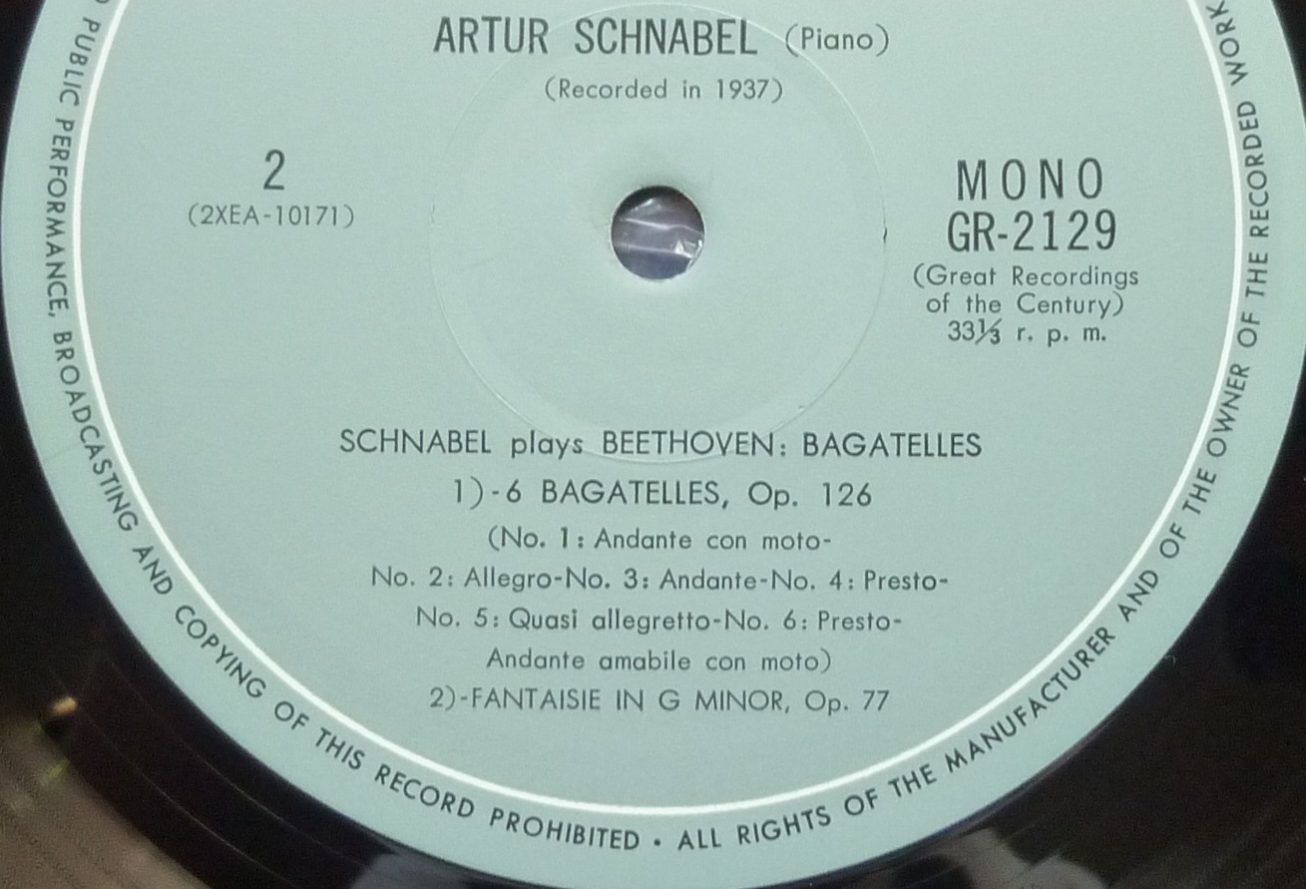

Bagatellen Op.33 – 10 novembre 1938

Bagatellen Op. 126 – 13 janvier 1937

Fantasia Op.77 – 14 janvier 1937

Rondo Op.51 n°1 – 13 avril 1933 – Rondo Op.129 – 13 janvier 1937 – Rondo WoO 49 – 14 janvier 1937

Menuet WoO 82 – Bagatelle WoO 59 – 10 novembre 1938

Artur Schnabel, piano

Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer Edward Fowler

33t. EMI-Toshiba GR 2120 & GR 2129

Ceci est le Volume I d’une série consacrée aux légendaires reports des enregistrements d’Artur Schnabel effectués par Anthony Griffith (1915-2005) et publiés en microsillon au Japon au milieu des années 60 par EMI-Toshiba. Leur particularité est qu’ils ont été non seulement réalisés à partir de pressages vinyle des matrices métalliques 78 tours d’origine, mais aussi qu’ils ont été reportés en 33 tours pratiquement sans aucun filtrage, et aucune autre édition ne reproduit aussi fidèlement le jeu du pianiste. Ils préservent également l’acoustique du studio d’enregistrement.

A la fin de l’année 1931, Fred Gaisberg (1873-1951), directeur artistique d’HMV a réussi à convaincre Artur Schnabel de faire des enregistrements. Le pianiste ne voulait pas fixer une fois pour toutes ses interprétations. Il avait aussi des exigences, notamment en ce qui concerne la reproduction de la dynamique. Pour caractériser les enregistrements, il utilisait le mot à double sens » Verplattung », signifiant aussi bien « mettre en disque » qu' »aplatir ». Son fils pianiste Karl-Ulrich était contre ces enregistrements, car il pensait que le matériel d’enregistrement n’était pas à même de reproduire (à titre de test) des effets tels que des sforzandos soudains, des basses bruyantes ou des excès de pédale, mais les premières prises réalisées l’ont lui aussi pleinement convaincu. Il faut dire aussi que les tous nouveaux Studios d’Abbey Road, inaugurés en novembre 1931, offraient de nombreuses nouvelles possibilités. HMV ayant accepté les conditions de Schnabel (enregistrer les 32 Sonates et les 5 Concertos de Beethoven, voire même toutes ses œuvres pour piano), un impressionnant programme d’enregistrement allant bien au delà du programme initial a pu être mené à bien entre janvier 1932 et janvier 1939 dans les Studios d’Abbey Road, au prix d’un considérable effort d’adaptation de la part du pianiste. Les Concertos étaient enregistrés au Studio n°1 et les œuvres pour piano seul et de musique de chambre au Studio n°3, avec toujours le même ingénieur du son, l’indispensable Edward Fowler (1902-1993) et toujours des pianos Bechstein.

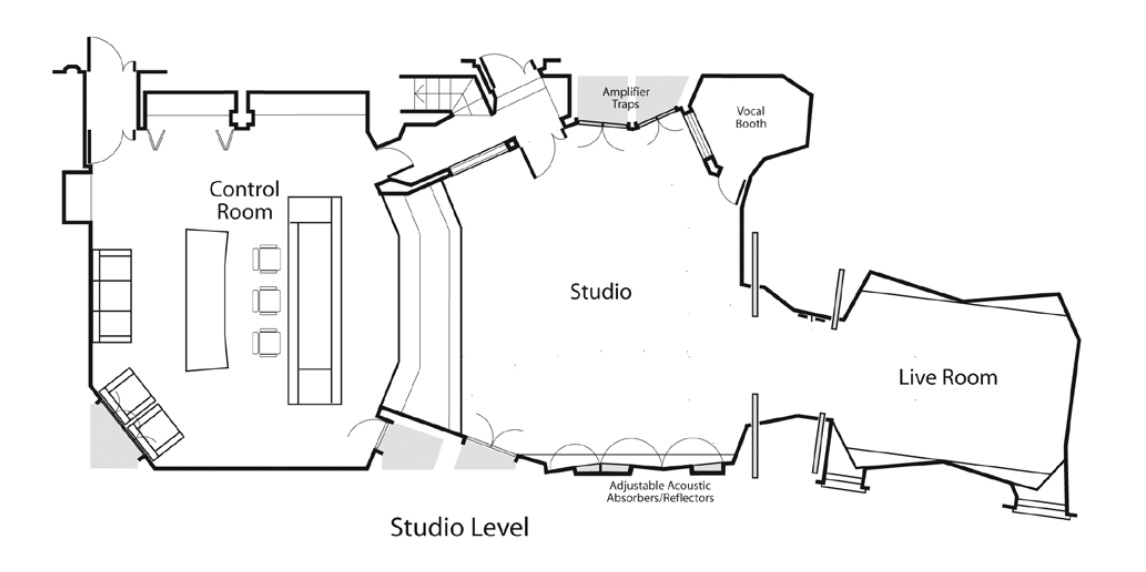

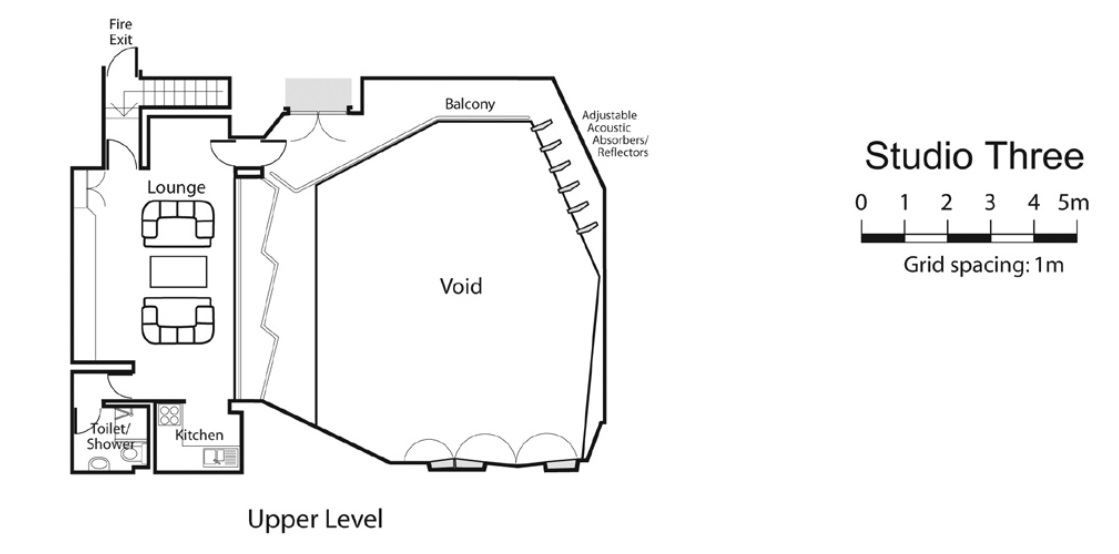

Le Studio n°3, où tant de grands pianistes ont enregistré, avait une surface étonnamment réduite (47 m2), une hauteur de 7,15 m et un temps de réverbération très court (réglable entre 0,7 et 1 seconde). Sa forme en polygone irrégulier a probablement été étudiée pour éviter des phénomènes de résonances et d’ondes stationnaires qui auraient coloré le son. Il comportait également un volume annexe (Live Room) pouvant être couplé ou non au Studio proprement dit.

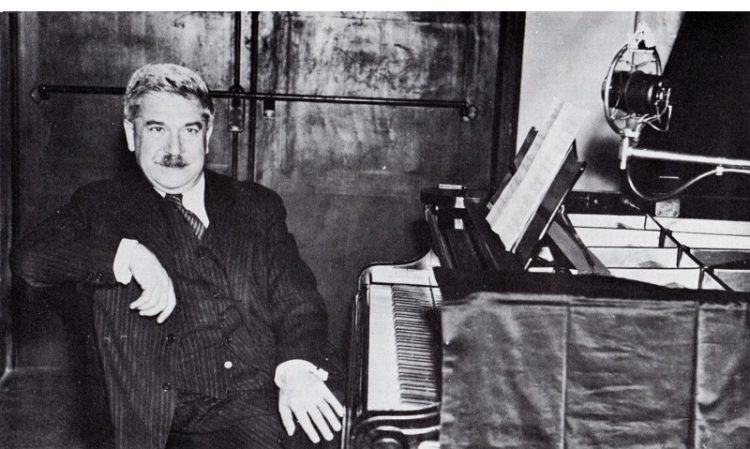

La photo ci-dessus, prise en 1939, montre que, pour ces séances, le piano était placé contre une paroi du Studio. On notera également la position proche et plutôt inhabituelle du microphone.

A l’époque de ces rééditions japonaises, Edward Fowler dirigeait les Studios d’Abbey Road. Anthony Griffith, responsable de ces reports, avait quant à lui participé en tant qu’ingénieur du son à des enregistrements de Schnabel en 1946 (Beethoven Concertos n° 2 & 4) et 1950 (Schubert Impromptus Op.90).

Edward Fowler

This is Volume I of a series dedicated to the legendary transfers of Artur Schnabel’s recording made by Anthony Griffith (1915-2005), and published as LPs in Japan by EMI-Toshiba in the mid-60s. They have been not only transferred from vinyl pressings of the original 78rpm metal parts, but also this has been done without any significant filtering, and no other edition reproduces the pianist’s playing so faithfully. The acoustics of the recording studio is also preserved.

Toward the end of 1931, Fred Gaisberg (1873-1951), HMV’s artistic director succeeded in convincing Artur Schnabel to make recordings. The pianist did not want his performances fixed for eternity. He also had concerns, especially about the reproduction of dynamics. To describe recordings, he used the double-meaning word » Verplattung », which meant « disc-making » as well as « flattening out ». His pianist son Karl-Ulrich was against the idea of his father’s recordings because he believed that the recording machines could not respond well to a test with sudden sforzandos, loud bass or too much pedal, but the first trial takes fully convinced him. It must be said that the brand new Abbey Road Studios, inaugurated in November 1931, offered many new possibilities. HMV having agreed to Schnabel’s demand (recording the 32 Sonatas and the 5 Concertos by Beethoven and even all of his piano works), an impressive recording program extending much further than this initial program was succesfully conducted between January 1932 and January 1939 in the Abbey Road Studios, at the cost of ajustments taxing the pianist’s adaptability to the utmost. The Concertos were recorded in Studio n°1, and the solo piano as well as chamber music works in Studio n°3, always with the same recording engineer, the indispensable Edward Fowler (1902-1993) and always with Bechstein pianos.

Studio n°3, where so many great pianists recorded, had an astonishingly small floor area (47 m2 or 506 sq.ft.), an height of 7.15 m (23 ft 5 in) and a quite short reverberation time (adjustable between 0.7 sec et 1 sec). Its roughly polygonal shape was probably chosen to avoid resonances or stationary waves which might have coloured the sound. He was also comprised of an extra volume (Live Room) which it was possible to couple to the Studio proper.

The above picture, taken in 1939, shows that, for these sessions, the piano was close to a wall of the Studio. Note also the close and rather unusual position of the microphone.

When these Japanese LP re-issues were made, Edward Fowler was at the head of the Abbey Road Studios. Remastering engineer Anthony Griffith had himsef taken part as recording engineer to Schnabel post-war recordings in 1946 (Beethoven’s Concertos n° 2 & 4) and 1950 (Schubert’s Impromptus Op.90).

______________

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

Symphonie n°4 D.417 – 23 & 24 octobre 1963

Symphonie n°5 D.485 – 21 & 22 octobre 1963

Prod: Ray Minshull Eng: Gordon Parry

(Bande 19cm/s 4 pistes London LCL 80143)

Wien Sofiensaal

Voici le Volume II avec les symphonies n°4 & 5 de Franz Schubert enregistrées en Octobre 1963 à la Sofiensaal de Vienne par les Wiener Philharmoniker sous la direction de Karl Münchinger.

Here is Volume II with Franz Schubert’s Symphonies n°4 & 5 recorded in October 1963 in Vienna at the Sofiensaal by the Wiener Philharmoniker conducted by Karl Münchinger.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.

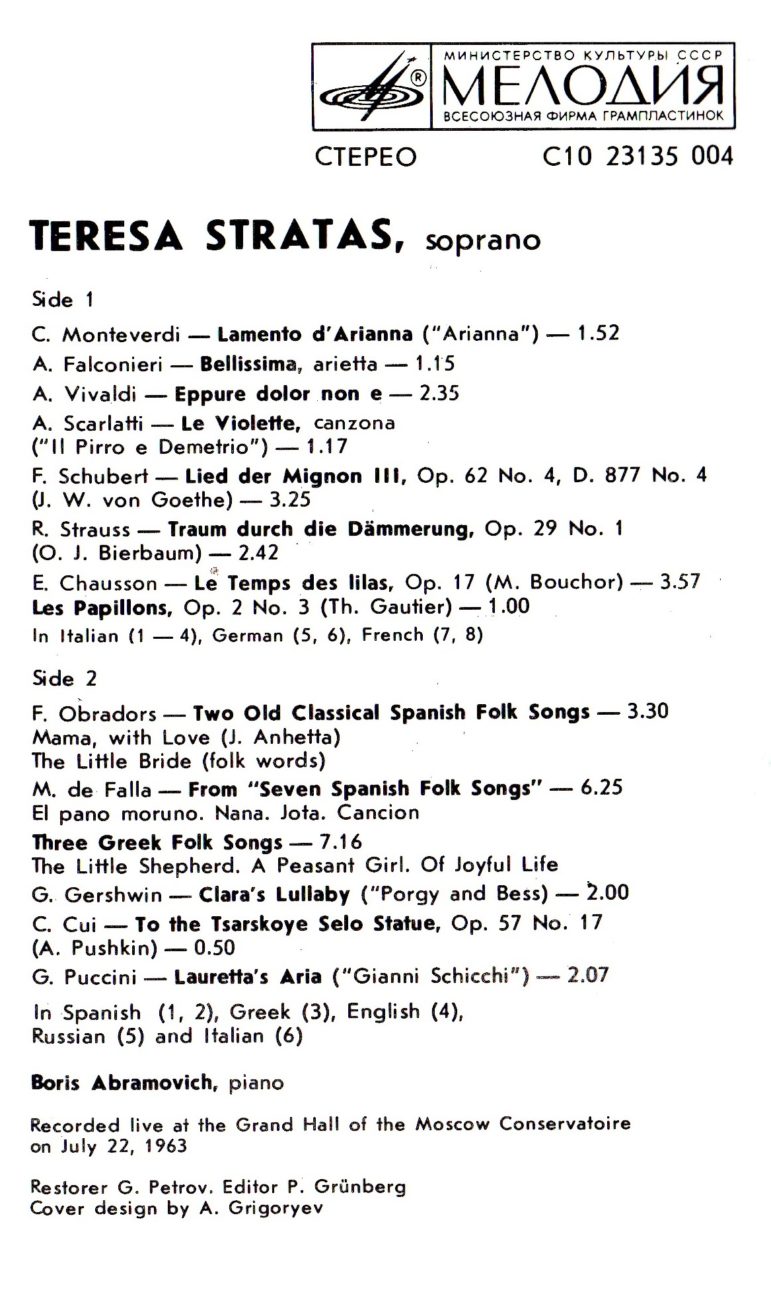

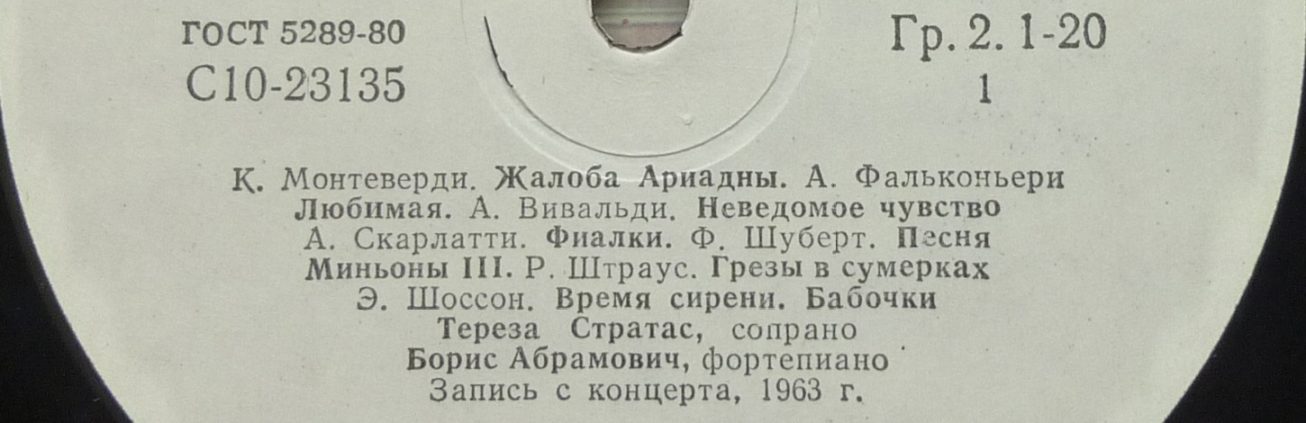

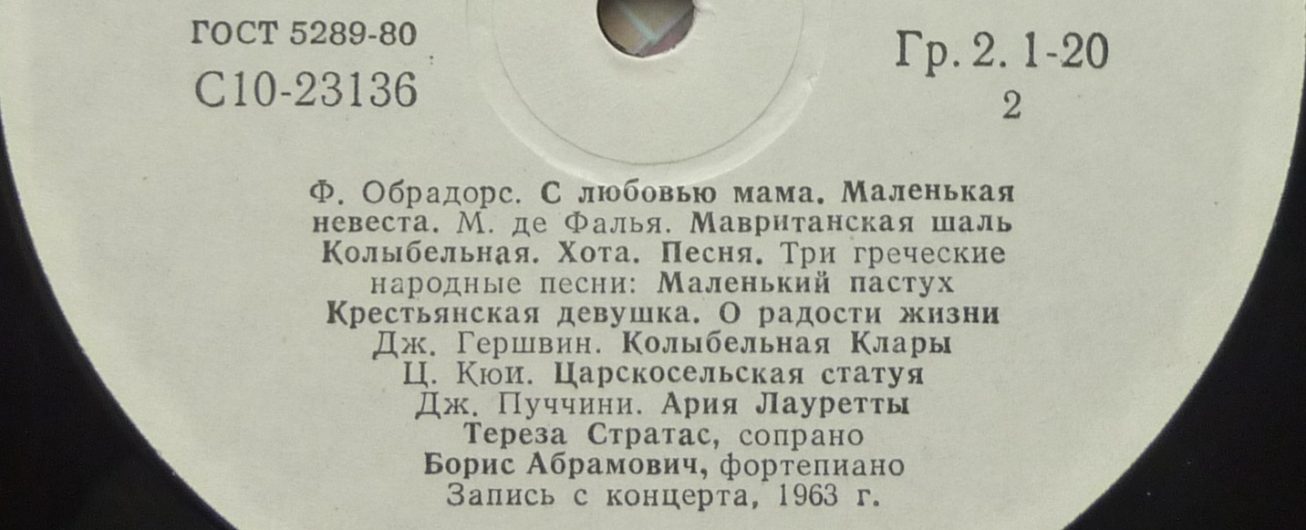

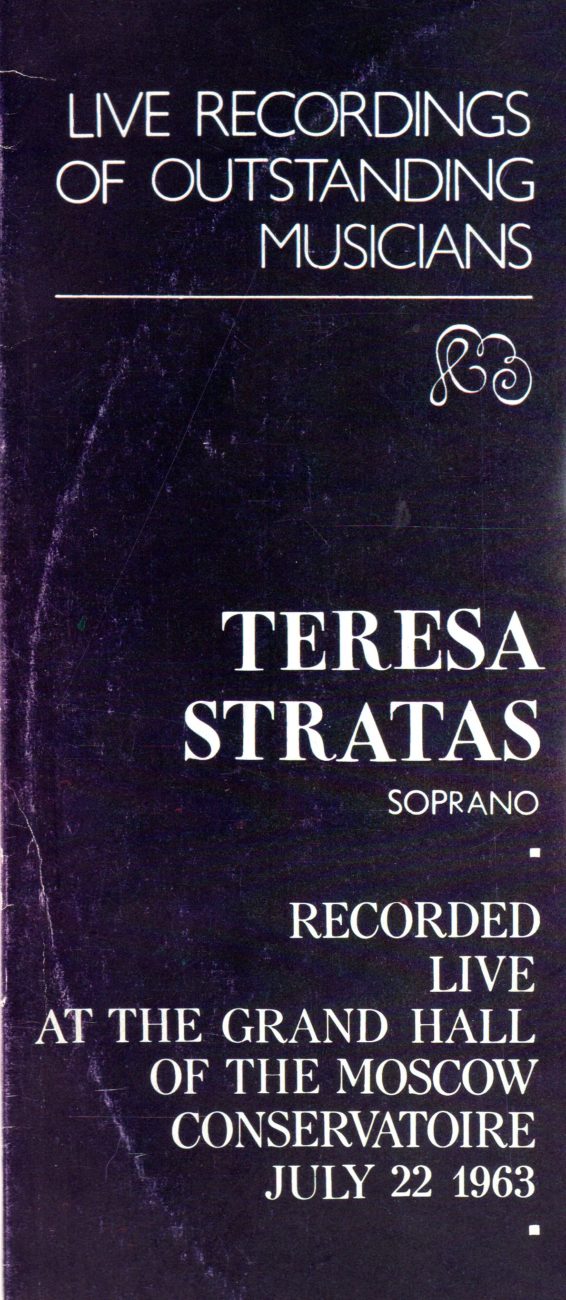

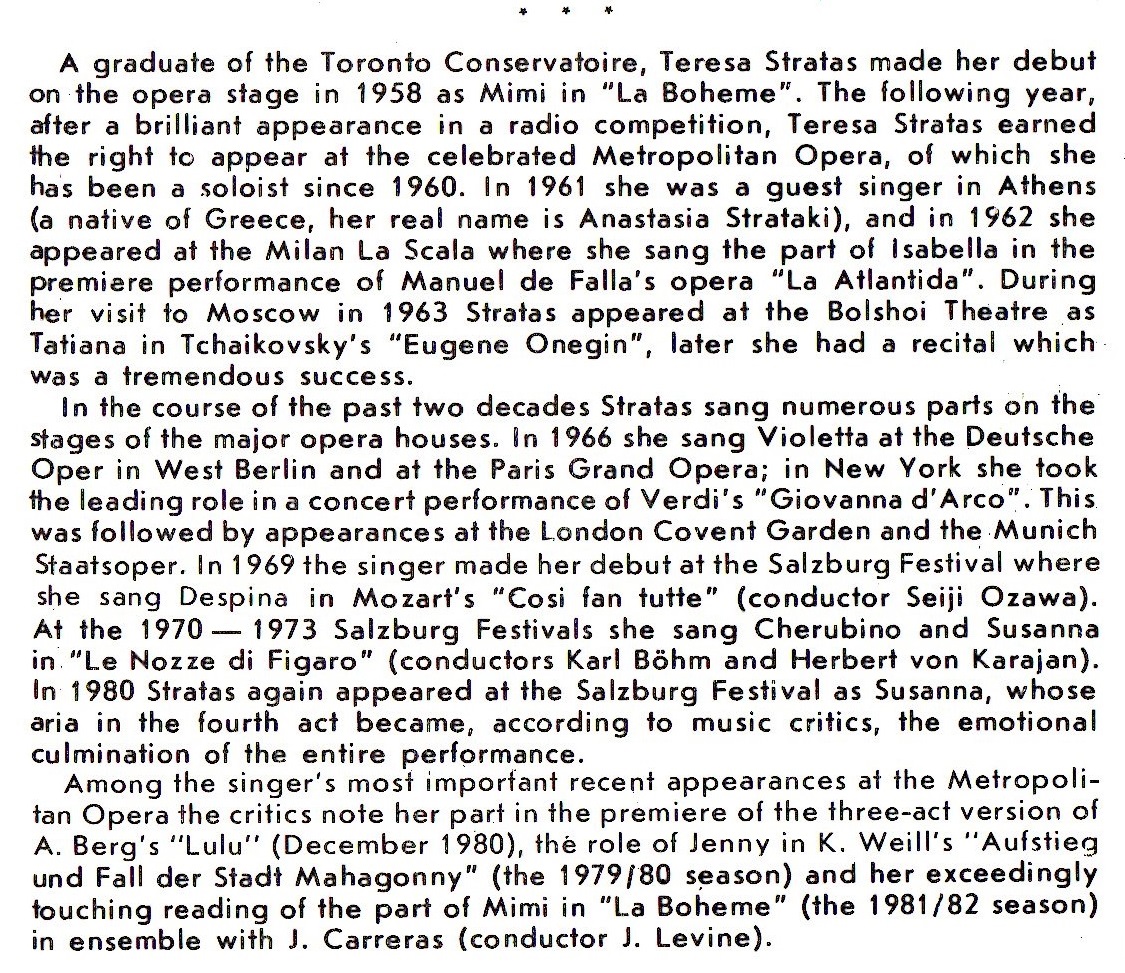

Teresa Stratas, soprano – Boris Abramovich, piano

Grande Salle du Conservatoire

A peine âgée de vingt-cinq ans, et en marge de représentations au « Bolchoï » (rien moins que le rôle de « Tatiana » dans « Eugène Onéguine »!), la soprano canadienne Teresa Stratas a donné ce récital dans la Grande Salle du Conservatoire Tchaïkovsky. Avec un fort bon pianiste, voici un périple musical dans (presque) tous les styles et toutes les époques, et sept langues différentes. A en juger par les applaudissements, ce fut un succès, qui fut même mémorable à tel point que, bien plus tard, en 1985, la firme Melodiya en a tiré un microsillon. Cerise sur le gâteau, le son est en stéréo.

Hardly twenty-five years old, and further to performances at the « Bolchoï » (with no less than the part of « Tatiana » in « Eugene Onegin »!), Canadian soprano Teresa Stratas gave this Recital in the Great Hall of the Tchaïkovsky Conservatory. With a quite good pianist, here is a musical tour in (nearly) all the styles and all the periods, and seven different languages. From the applause, it was a success, and even a memorable one, to such an extend that, much later, in 1985, the Melodiya firm made a LP of it. As a bonus, the sound is in stereo.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment.