Mozart – Fine Arts Quartet

Horn Quintett K.407 John Barrows, Horn

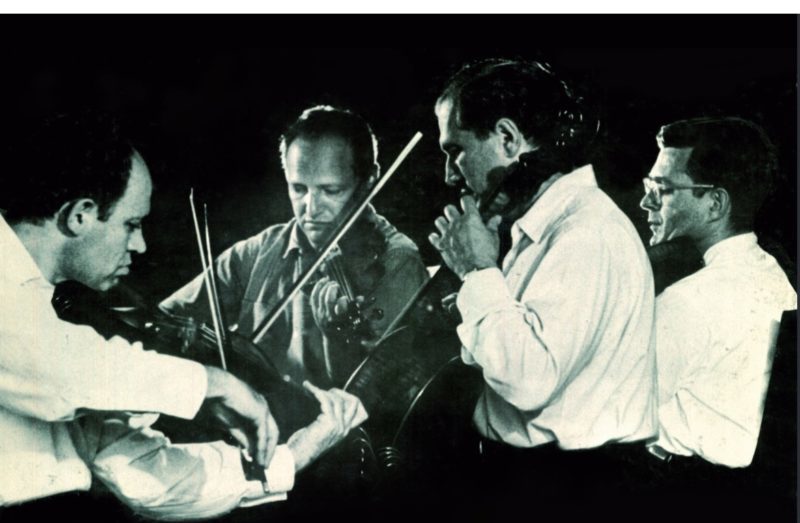

Leonard Sorkin, Violin; Abram Loft, Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin Cello

Oboe Quartett K.370 Ray Still, Oboe

Leonard Sorkin, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello

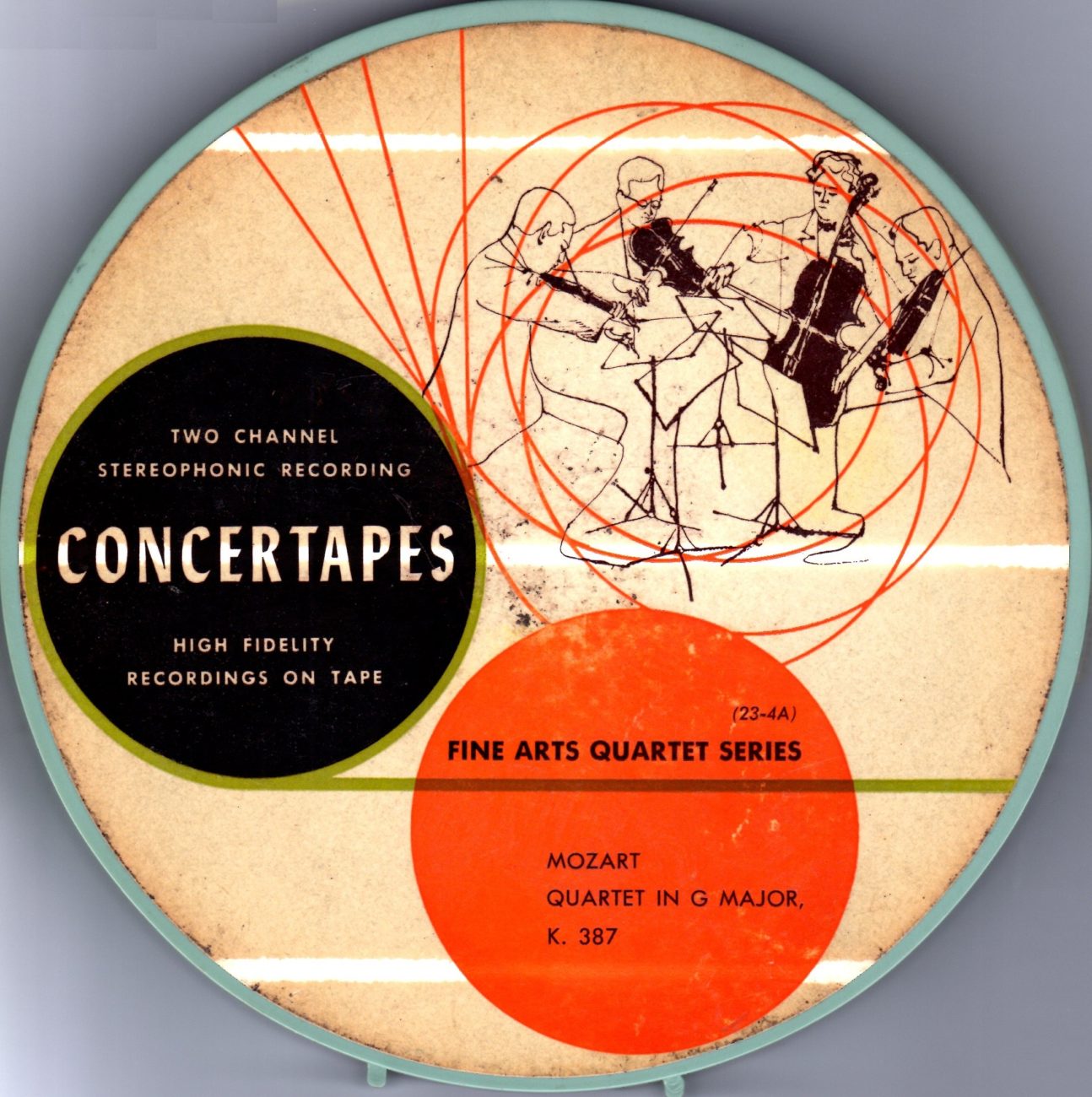

Quartett n°14 K.387

Leonard Sorkin, Abram Loft, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello

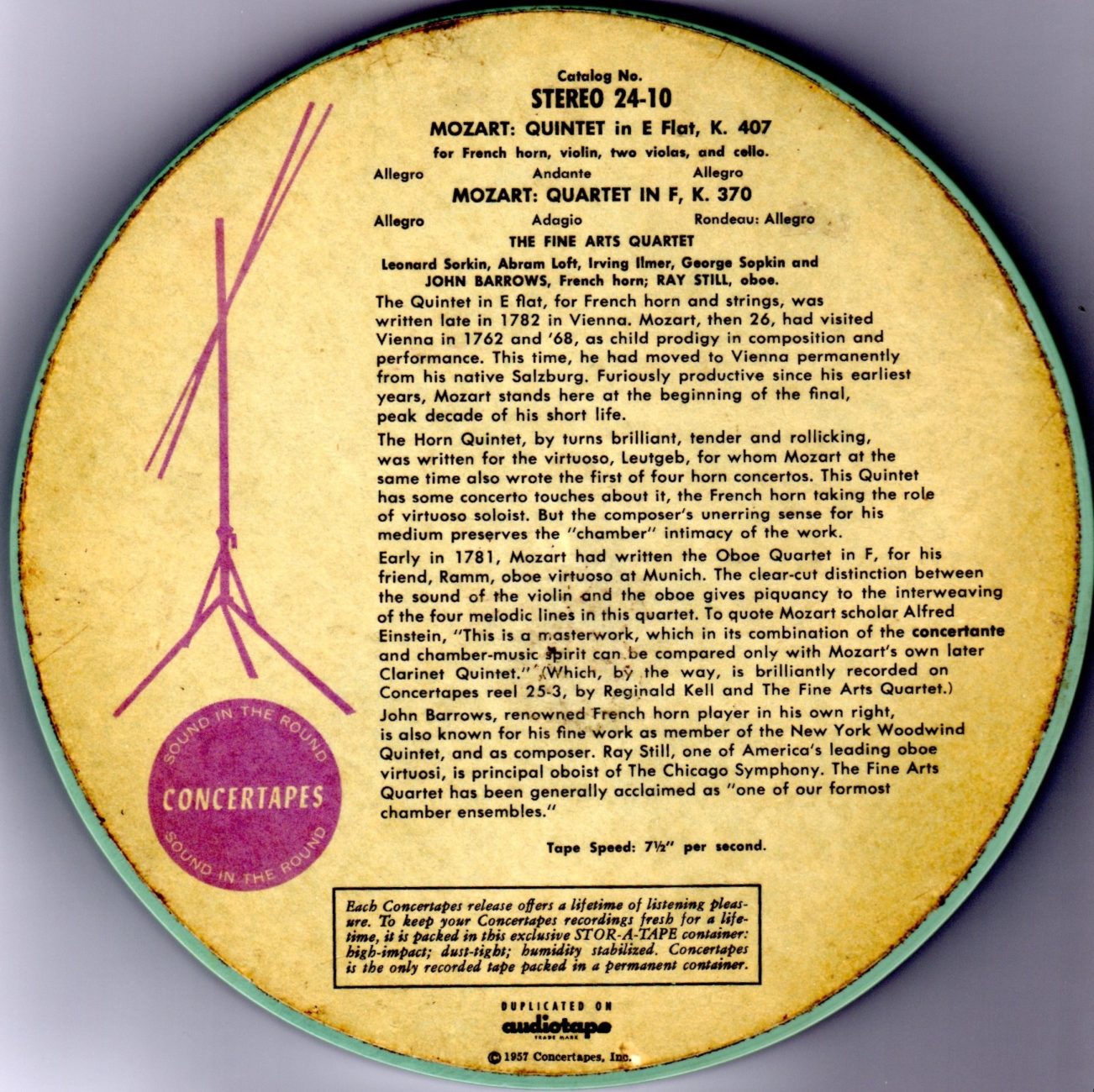

Enregistrement/Recording: 1954/1955 (K.387) & 1956/1957 (K. 407 & K.370)

Source: Bande/Tape – 2 pistes 19cm/s / 2tracks 7.5 ips STEREO

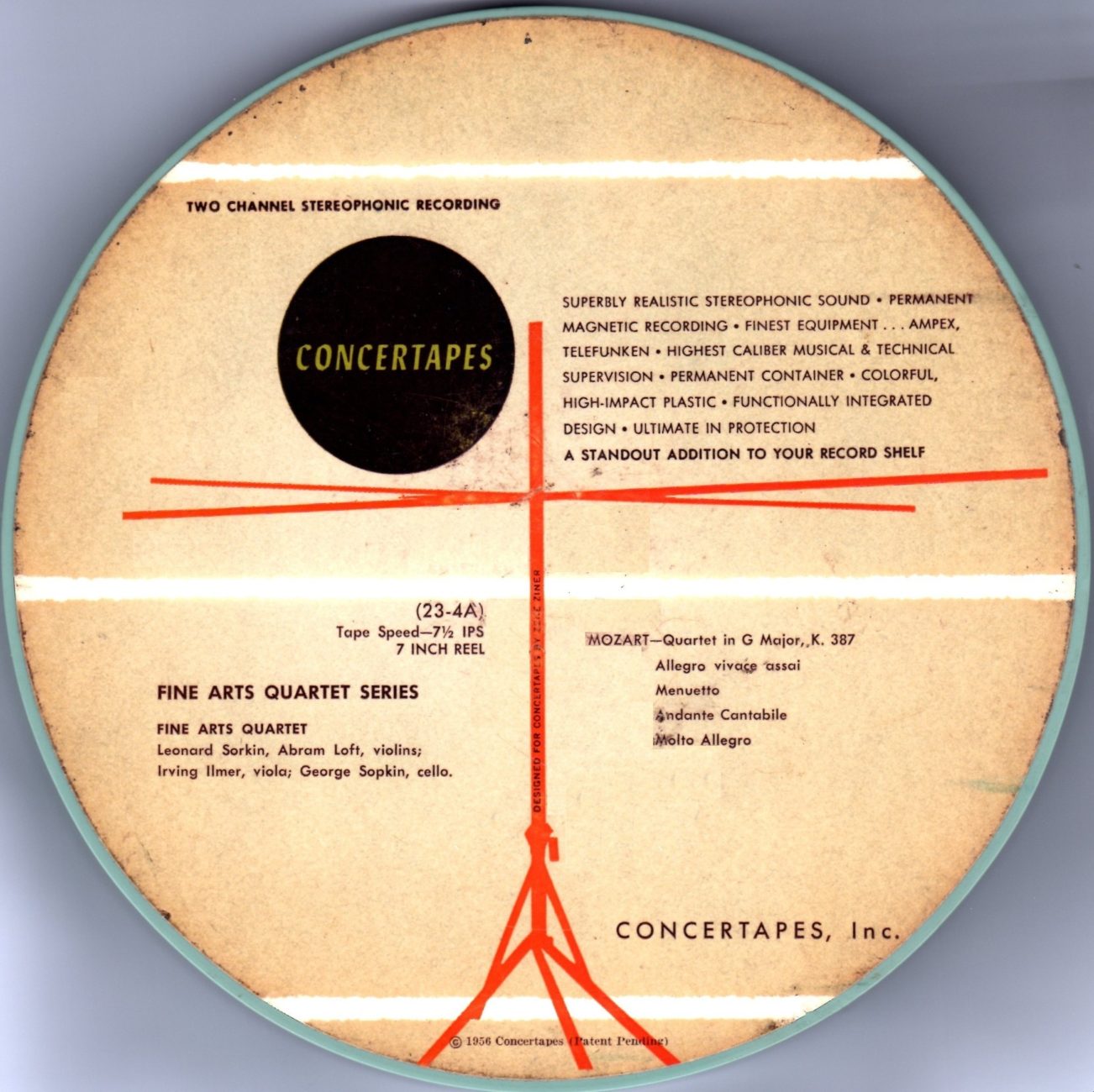

Concertapes 24-10 (K. 407 & K.370) & 23-4A (K.387)

Le Quintette avec cor K.407 présente la particularité de ne comporter qu’un seul violon, et deux altos. Pour cet enregistrement, Abram Loft joue le premier alto, et Irving Ilmer, le deuxième.

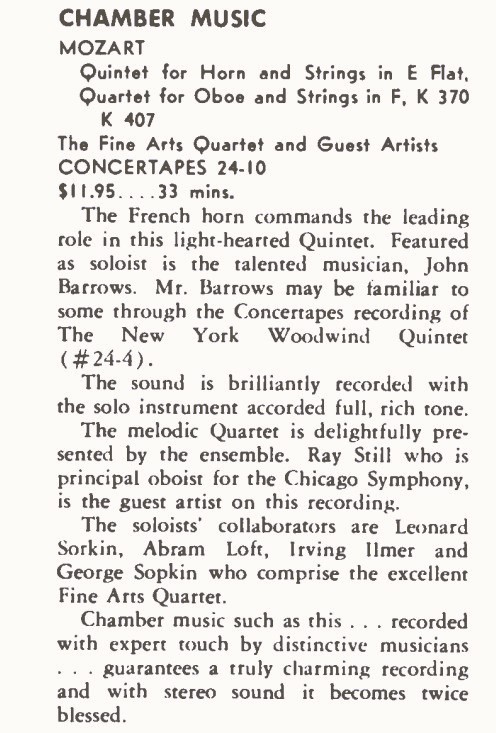

Il est assez difficile de déterminer la date des enregistrements du Fine Arts Quartet pour Webcor/Concertapes. L’enregistrement du Quatuor n°14 K.387, le premier de la série dédiée à Joseph Haydn, a été publié tout d’abord en mono par Webcor sur la piste A de la bande 2923-4 qui a été critiquée dans le numéro de juillet 1955 de la revue High Fidelity, et ensuite en stéréo en 1956 sous le label Concertapes sur la bande référencée 23-4A. La date de 1954-1955 donnée sur le site officiel du Quatuor est donc pertinente. Par contre, la date donnée sur ce même site (1958) pour les deux autres œuvres (K407 & K370) ne peut être retenue, car la bande stéréo Concertapes 24-10 porte 1957 comme date de publication.

Le Quintette K.407 et le Quatuor K.370 font partie de la réédition (en 2016) des enregistrements du Fine Arts Quartet. Par contre, le Quatuor K.387 n’a pas été réédité depuis les années cinquante et est donc une rareté discographique.

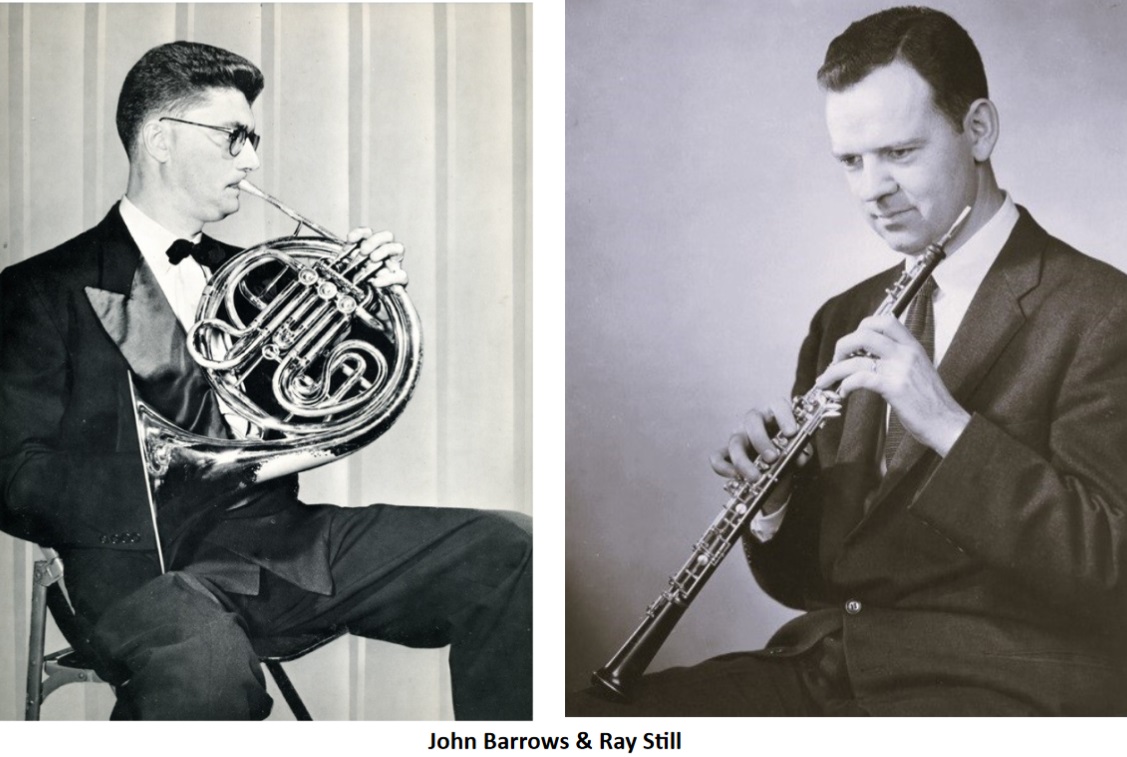

Le corniste John Barrows (1913-1974) a eu pour professeurs Richard Donovan et David Smith. Membre du Minneapolis Symphony en 1938, il a ensuite été pendant la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale chef adjoint de l’Army Airforce Band, puis, à New York, il a joué avec le City Opera (1946-1949) et le City Ballet (1952-1956). En 1952, il a co-fondé le New York Woodwind Quintet (avec Samuel Baron, flûte, Jerome Roth, hautbois, David Glazer, clarinette et Bernard Garfield, basson), ensemble qui a fait plusieurs enregistrements pour Concertapes, notamment avec le Fine Arts Quartet.

Ray Still (1920-2014) a commencé sa carrière en 1939 comme second hautbois du Kansas City Philharmonic (1939-1941). Après avoir servi dans l’armée jusqu’en juin 1946, il a suivi l’enseignement de Robert Bloom à la Juilliard School, et ensuite il a été de 1947 à 1949 hautbois solo du Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, alors dirigé par William Steinberg après quoi il a occupé le même poste pendant quatre ans au Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. En 1953, après une audition devant Fritz Reiner, il a été engagé comme second hautbois au Chicago Symphony Orchestra, et promu premier hautbois l’année suivante. Il est resté à ce poste jusqu’en 1993.

Tape Recording – Janvier/ January 1959

High Fidelity – Juillet/July 1955

The Quintet with Horn K.407 is unusual in that it features only one violin, and two violas. For this recording, Abram Loft plays the first viola, and Irving Ilmer the second.

It is rather difficult to determine the date of the Fine Arts Quartet’s recordings for Webcor/Concertapes. The recording of Quartet K.387, the first in the series dedicated to Joseph Haydn, was first released in mono by Webcor on track A of tape 2923-4, which was reviewed in the July 1955 issue of High Fidelity magazine, and then in stereo in 1956 on the Concertapes label with tape referenced 23-4A. The 1954-1955 date given on the Quartet’s official website is therefore relevant. On the other hand, the date given on the same site (1958) for the other two works (K407 & K370) cannot be held as valid, as the Concertapes 24-10 stereo tape bears 1957 as the publication date.

The Quintet K.407 and the Quartet K.370 are part of the Fine Arts Quartet’s 2016 reissued recordings. The Quartet K.387, on the other hand, has not been reissued since the 1950s, and is therefore a recording rarity.

Horn player John Barrows (1913-1974) was taught by Richard Donovan and David Smith. A member of the Minneapolis Symphony in 1938, he was assistant conductor of the Army Airforce Band during the Second World War, and later played in New York with the City Opera (1946-1949) and the City Ballet (1952-1956). In 1952, he co-founded the New York Woodwind Quintet (with Samuel Baron, flute, Jerome Roth, oboe, David Glazer, clarinet and Bernard Garfield, bassoon), an ensemble that has made several recordings for Concertapes, notably with the Fine Arts Quartet.

Ray Still (1920-2014) began his career in 1939 as second oboist of the Kansas City Philharmonic (1939-1941). After serving in the army until June 1946, he studied with Robert Bloom at the Juilliard School, and from 1947 to 1949 was principal oboe of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, then conducted by William Steinberg, after which he held the same position for four years with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. In 1953, after auditioning for Fritz Reiner, he was hired as second oboe with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and promoted to principal oboe the following year. He remained in this position until 1993.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

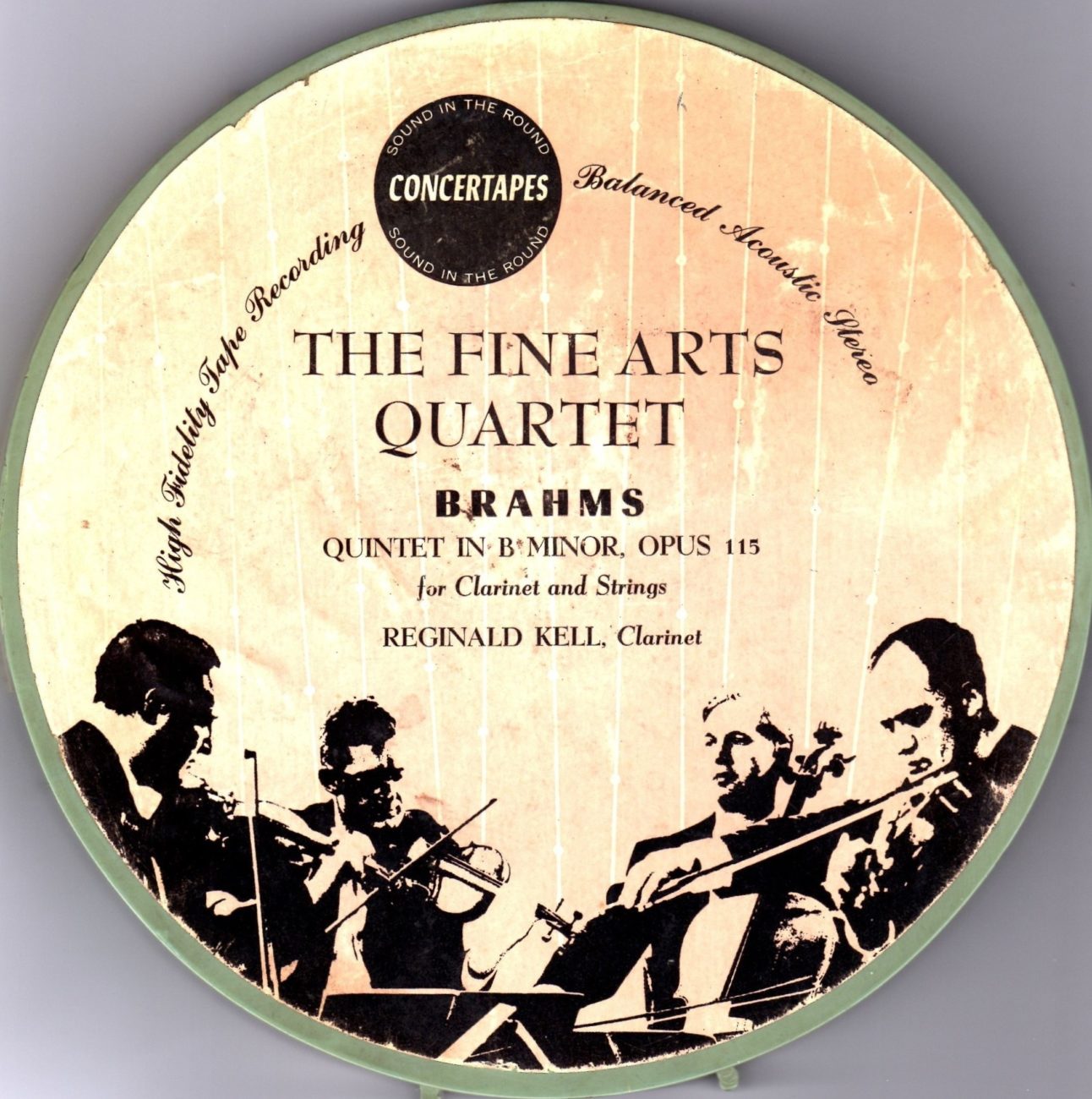

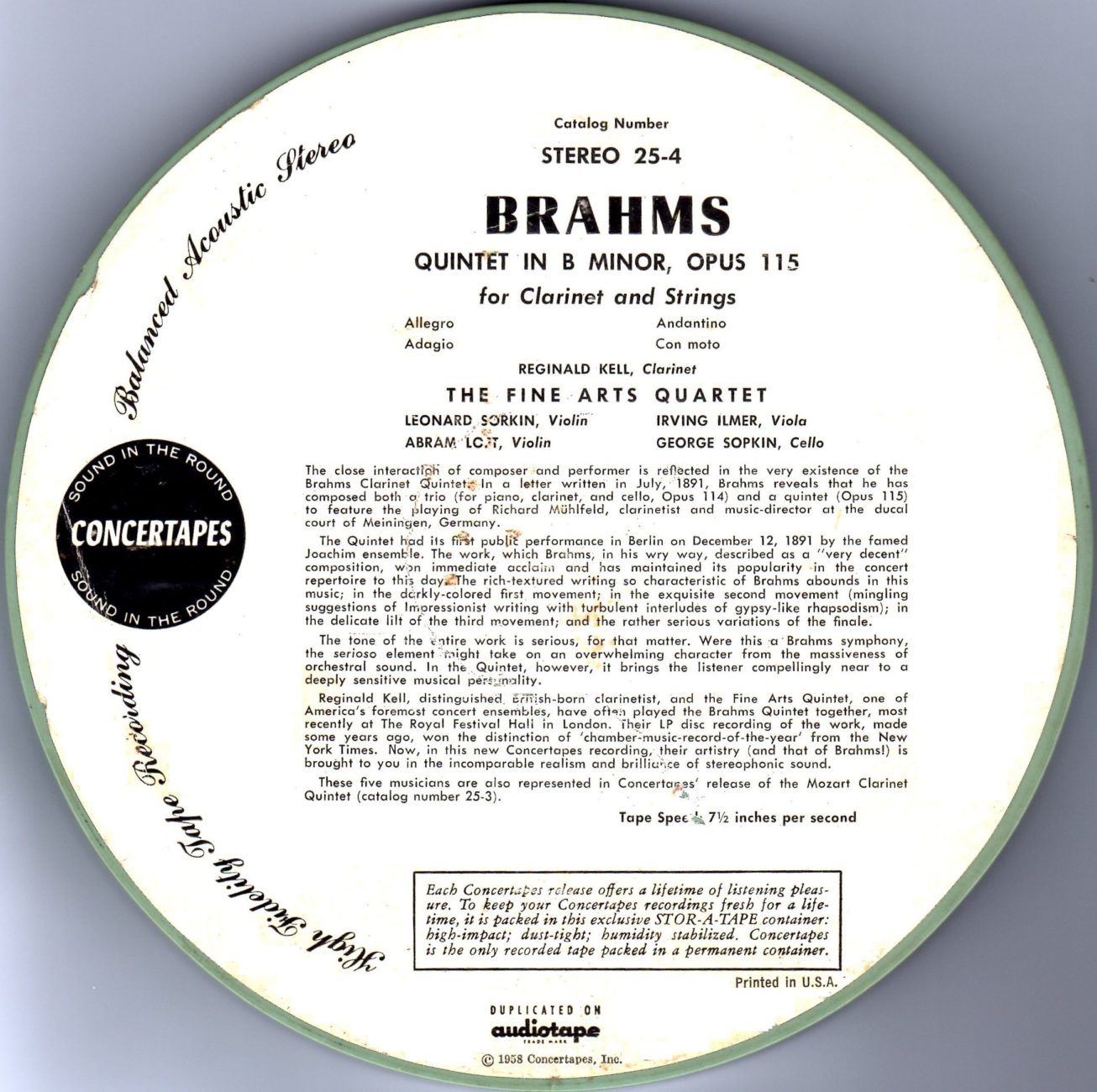

Johannes Brahms Klarinettenquintett Op. 115

Reginald Kell, Clarinet

Fine Arts Quartet (Leonard Sorkin, Abram Loft, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello)

Enregistrement/Recording: 1957

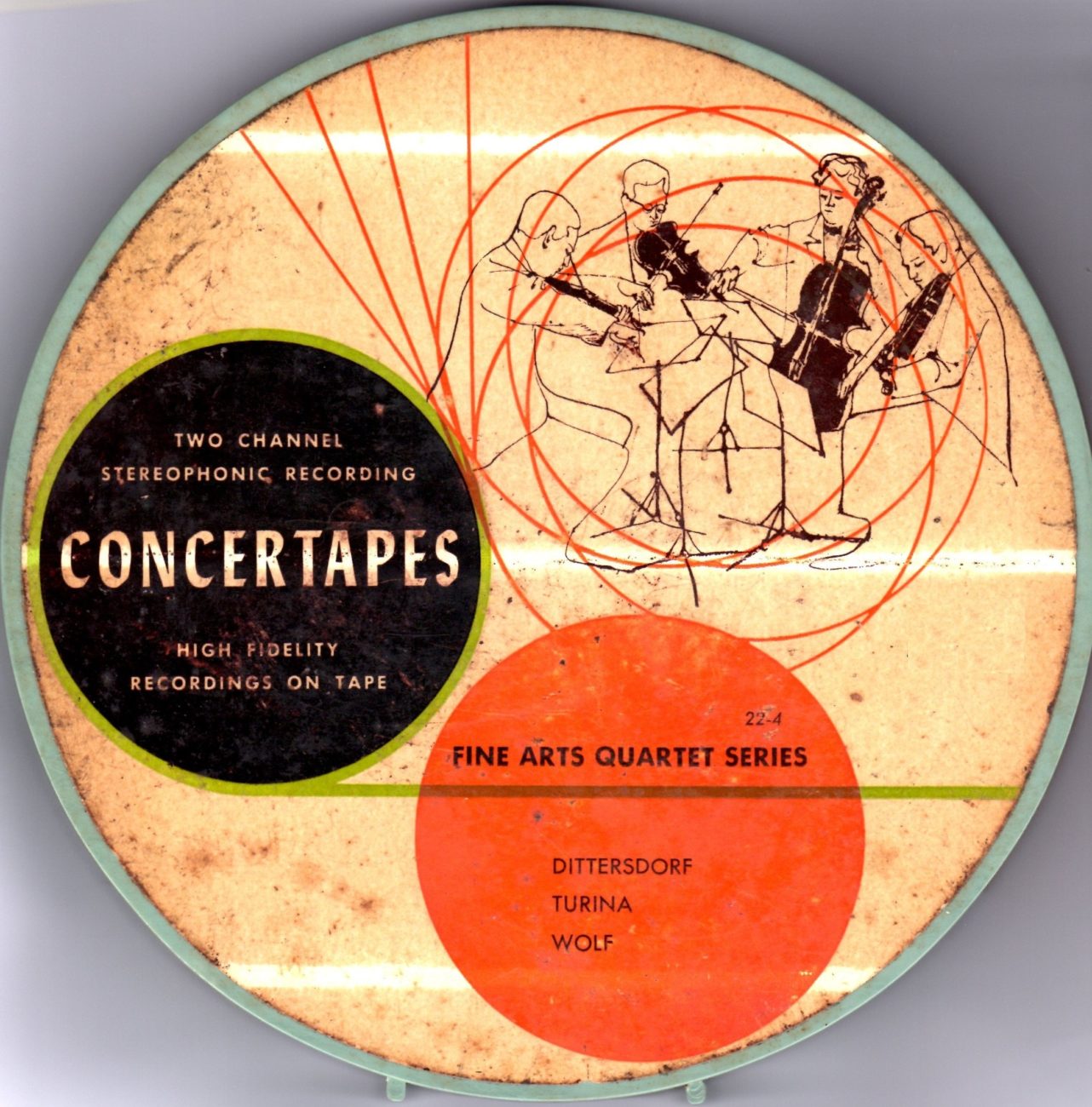

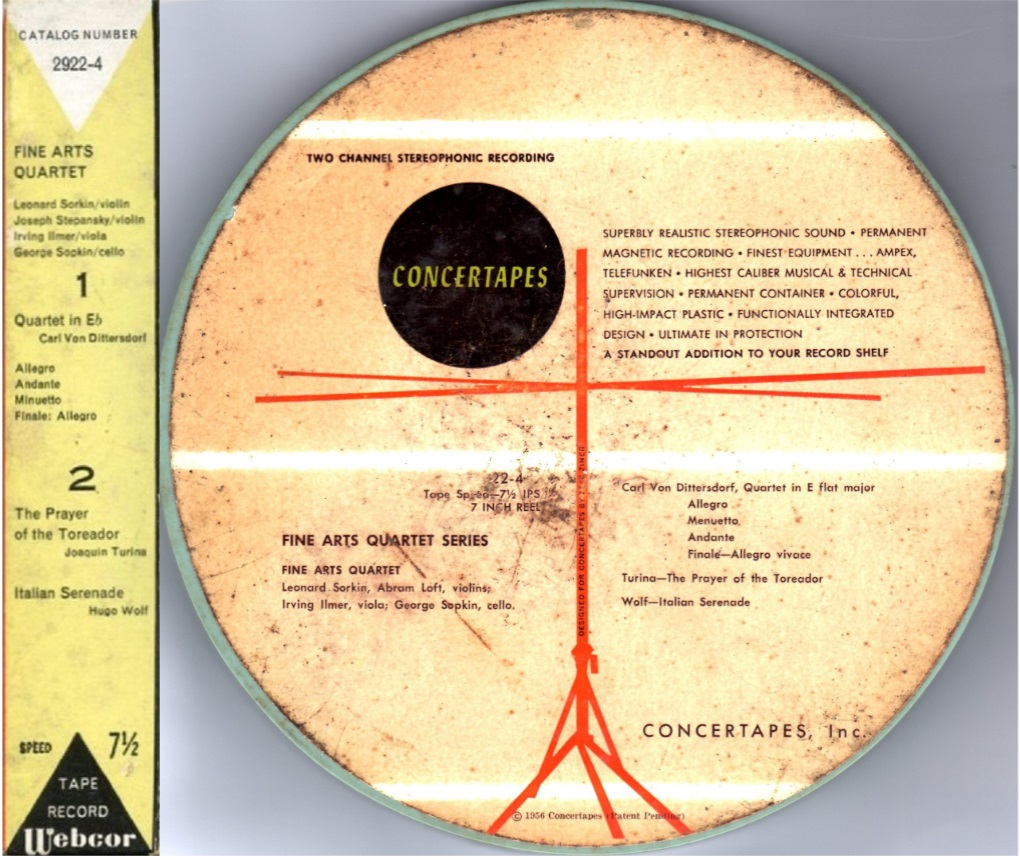

Hugo Wolf Italienische Serenade

Fine Arts Quartet (Leonard Sorkin, Joseph Stepansky, Violin; Irving Ilmer, Viola; George Sopkin, Cello)

Enregistrement/Recording: 1953/1954

Source: Bande/Tape – 2 pistes 19cm/s / 2tracks 7.5 ips STEREO

Concertapes 25-4 (Brahms) & 22-4 (Wolf)

Cet enregistrement du Quintette de Brahms Op.115 n’a pas été réédité depuis 1995, et celui de la Sérénade de Wolf ne l’a pas été depuis sa première parution dans les années cinquante. Ce sont donc des raretés discographiques.

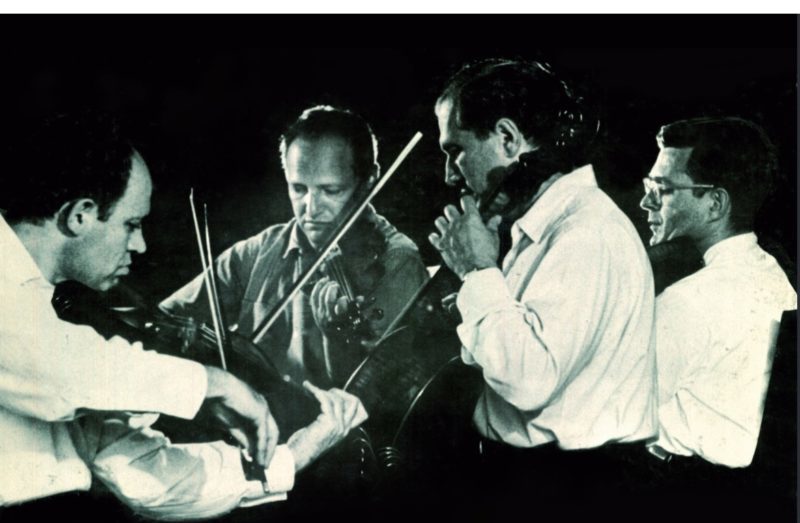

Le Fine Arts Quartet a été fondé en 1940 par quatre musiciens du Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO), à savoir Leonard Sorkin (1916-1985), Bernard Senescu (1904-1968), Sheppard Lehnhoff (1905-1978) et George Sopkin (1914-2008). En raison de la guerre et de la conscription, le quatuor n’a pu commencer à donner régulièrement des concerts qu’à partir de 1946, avec un nouveau deuxième violon, Joseph Stepansky (1916-1984). En 1952, l’altiste Sheppard Lehnhoff a quitté le quatuor pour réintégrer le CSO et a été remplacé par Irving Ilmer (1919-1997) qui à son tour a été remplacé en 1963 par Gerald Stanick, puis en 1968 par Bernard Zaslav. En 1954, Joseph Stepansky a été remplacé par Abram Loft (1922-2019). Il n’y aura plus de changement jusqu’en 1979 avec le départ d’Abram Loft et de George Sopkin. Leonard Sorkin a quitté le quatuor en 1982 pour être remplacé par Ralph Evans, qui en est toujours le premier violon.

De 1946 à 1954, le Fine Arts Quartet a participé à des émissions radiophoniques hebdomadaires le dimanche matin pour l’ ‘American Broadcasting Company’ (ABC) de Chicago. ainsi qu’à des émissions éducatives télévisées. Il était également un pionnier de l’enregistrement stéréo. Avec le label Webcor (Webster Chicago Corporation), à l’origine un fabricant de magnétophones, puis Concertapes, le label qui a été fondé par le Fine Arts Quartet et lui appartenait, ce qui était rare à l’époque, le Quatuor a réalisé tous ses enregistrements en stéréo à partir de 1953 (notamment Dvorak Op.96 ‘Américain’ et Debussy), avec en 1958 une Intégrale très remarquée des quatuors de Bartók. Un certain nombre de ces enregistrements ont été réédités en 2016 (téléchargement HD), mais ni le Quintette de Brahms, ni la Sérénade d’Hugo Wolf. n’en faisaient partie, alors qu’on y trouvait le Quintette K.581 de Mozart, que Kell a également enregistré en 1957 avec le Fine Arts Quartet, ce qui laisse supposer que la bande originale du Brahms était en mauvais état au point de n’avoir pas pu être copiée. Les Quintettes de Mozart et de Brahms de 1957 ont été les tous derniers enregistrements de Kell, après quoi, il est retourné en Grande-Bretagne en janvier 1958.

Reginald Kell (1906-1981) a enregistré trois fois le Quintette Op.115 de Brahms: le 10 Octobre 1937, avec le Busch Quartet (Abbey Road – Studio n°3), une version mono avec le ‘Fine Arts Quartet of the American Broadcasting Company’ pour American Decca (New York – 2 au 5 Octobre 1951), réédité par DGG dans le coffret de 6CD ‘Reginald Kell the complete ‘American Decca’ recordings’ (00289 477 5280), et enfin, en 1957, le présent enregistrement stéréophonique pour Concertapes, publié sur bandes et en microsillon. Sa dernière publication en microsillon date de 1978 (Concert Hall SMS 2530), et il n’y eut qu’une seule édition en CD, en 1995 (Boston Skyline SD 135), ‘à partir de copies de première génération des bandes originales, conservées par M. Sopkin’.

Dans le numéro du printemps 1999 de l’International Classical Record Collector (ICRC), dans un article sur Reginald Kell, Norman C. Nelson a écrit à propos de cet enregistrement : ‘Le Quintette de Brahms avec les Fine Arts présente l’inconvénient apparemment insurmontable d’être précédé par la version incandescente avec le Quatuor Busch. Ce qui est surprenant, après la formidable impression laissée par l’enregistrement précédent, c’est l’excellence de l’interprétation des Fine Arts, qui présente un jeu plus actif et plus vivant que pour le Quintette de Mozart. L’intensité n’est cependant pas aussi soutenue que dans l’enregistrement avec les Busch, qui tient l’auditeur à la gorge de la première à la dernière note. Le rubato appliqué par Kell dans les premiers passages de clarinette du Quintette est similaire dans les deux enregistrements, bien qu’une vingtaine d’années les séparent. Les deux interprétations avec le Fine Arts restent de belles interprétations dans lesquelles Kell démontre sa maîtrise de l’instrument et son talent artistique unique à la fin de sa carrière d’enregistrement. Seule une légère diminution de la concentration de son timbre est perceptible. Le son du dernier enregistrement est nettement supérieur à celui des deux premiers, en particulier le Brahms de 1937, et certains pourraient même préférer le jeu des cordes plus moderne des Fine Arts au style plus ancien des Busch, qui comprend de nombreux cas de « portamento ».

La Sérénade de Wolf fait partie des quelques enregistrements réalisés par Webcor en 1953 ou 1954, avant que Joseph Stepansky ne soit remplacé par Abram Loft. Webcor l’a publié sur une bande mono (2922-4). La bande stéréo (22-4), publiée en 1956 par Concertapes, mentionne de manière erronée Abram Loft en tant que deuxième violon.

Reginald Kell

The 1957 recording of the Brahms Quintet Op.115 has not been reissued since 1995, and that of the Wolf’s Serenade has not been reissued at all since its first release in the 1950s. They are therefore discographic rarities.

The Fine Arts Quartet was founded in 1940 by four musicians from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO): Leonard Sorkin (1916-1985), Bernard Senescu (1904-1968), Sheppard Lehnhoff (1905-1978) and George Sopkin (1914-2008) . Because of the war and conscription, the quartet was unable to begin giving regular concerts until 1946, but with a new second violinist, Joseph Stepansky (1916-1984). In 1952, violist Sheppard Lehnhoff left the quartet to rejoin the CSO and was replaced by Irving Ilmer (1919-1997), who in turn was replaced in 1963 by Gerald Stanick, then in 1968 by Bernard Zaslav. In 1954, Joseph Stepansky was replaced by Abram Loft (1922-2019). There were no further changes until 1979 with the departure of Abram Loft and George Sopkin. Leonard Sorkin left the quartet in 1982 to be replaced by Ralph Evans, who is still first violin.

From 1946 to 1954, the Fine Arts Quartet took part in weekly Sunday morning radio broadcasts for Chicago’s American Broadcasting Company (ABC), as well as educational television programmes. He was also a pioneer of stereo recording. With the Webcor label (Webster Chicago Corporation), originally a manufacturer of tape recorders, and later Concertapes, the label which was founded by and belonged to the Fine Arts Quartet, which was quite rare then, the Quartet made all his recordings in stereo from 1953 onwards (notably Dvorak Op.96 ‘Américain’ and Debussy), with a highly acclaimed complete recording of Bartók’s quartets in 1958. A number of these recordings were re-issued in 2016 (‘Hi-Res’ download), but neither the Brahms Quintet nor the Hugo Wolf’s Serenade were included, although they did include Mozart’s Quintet K.581, which Kell also recorded in 1957 with the Fine Arts Quartet, which probably means that the master tape of the Brahms was in poor condition to the point of being unplayable. The 1957 Mozart and Brahms Quintets were Kell’s last recordings, after which he returned to Britain in January 1958.

Reginald Kell (1906-1981) made three recordings of Brahms’s Quintet Op.115: on 10 October 1937, with the Busch Quartet (Abbey Road – Studio No. 3), a mono version with the ‘Fine Arts Quartet of the American Broadcasting Company’ for American Decca (New York – 2 to 5 October 1951), reissued by DGG in the 6CD box set ‘Reginald Kell the complete ‘American Decca’ recordings‘ (00289 477 5280), and finally, in 1957, the present stereophonic recording for Concertapes, issued on tape and LP. It was last released on LP in 1978 (Concert Hall SMS 2530), and there has only been one CD release, in 1995 (Boston Skyline SD 135), ‘from first-generation studio masters, preserved by Mr Sopkin’.

In the Spring 1999 Issue of International Classical Record Collector (ICRC), in an article on Reginald Kell, Norman C. Nelson wrote about this recording: ‘The Brahms Quintet with the Fine Arts is at the apparently unsuperable disadvantage of being preceded by the incandescent version with the Busch Quartet. What is surprising, after the terrific impression made by the earlier recording, is the excellence of the Fine Arts performance, which features more urgent, vivid playing than their Mozart Quintet. The intensity, however, is not as sustained as in the Busch recording, which has the listener by the throat from first note to last. The rubato applied by Kell in the opening clarinet passages of the Quintet is similar in both recordings though some 20 years separated them. Both performances with the Fine Arts remain lovely ones in which Kell demonstrates his continuing grip on the instrument and unique artistry at the close of his recording career. Only a slight diminution in the focus of his tone is noticeable. The sound on the last recording is clearly superior to their early counterparts, especially the 1937 Brahms, and some may even prefer the more modern string playing of the Fine Arts to the older style of the Buschs, which includes numerous instances of portamento’.

Wolf’s Serenade is one of the few recordings made by Webcor in 1953 or 1954, before Joseph Stepansky was replaced by Abram Loft. Webcor released it on a mono tape (2922-4). The stereo tape (22-4), published in 1956 by Concertapes, incorrectly lists Abram Loft as second violin.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

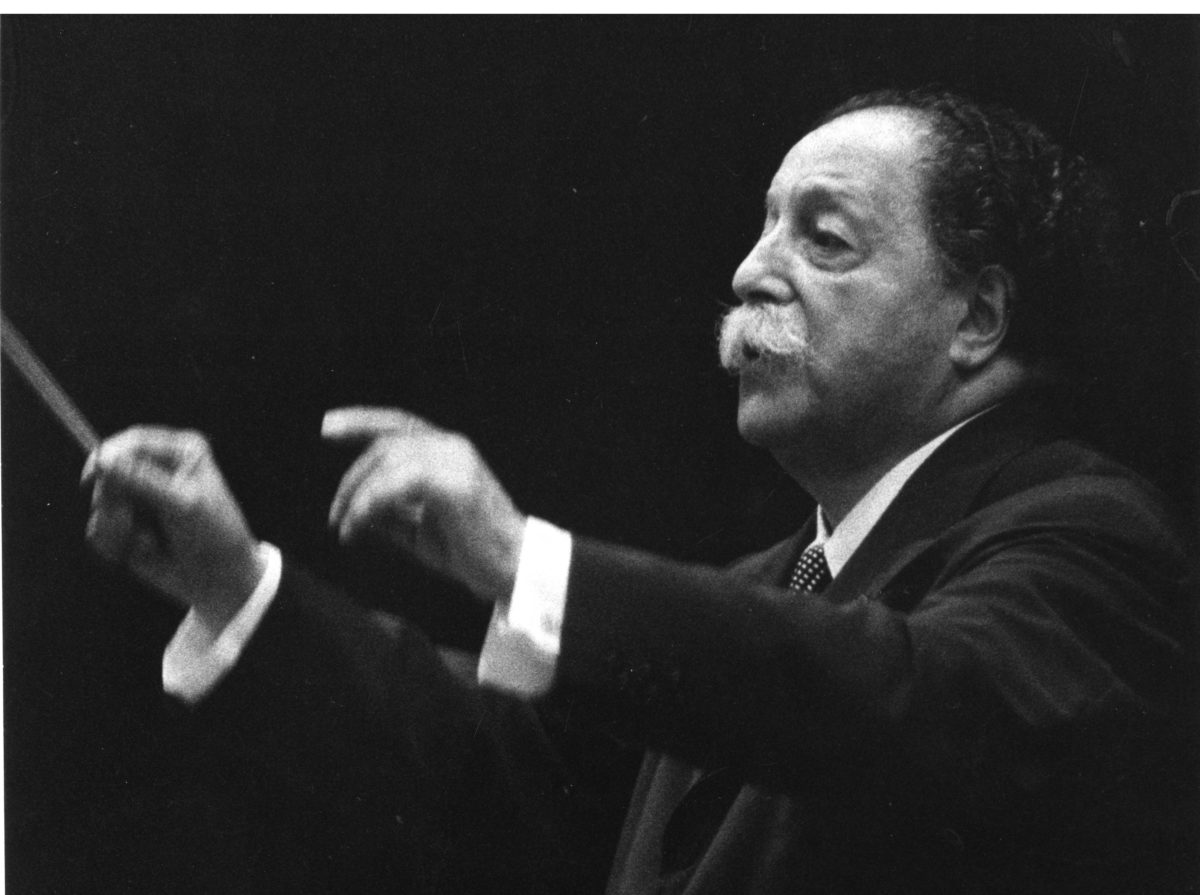

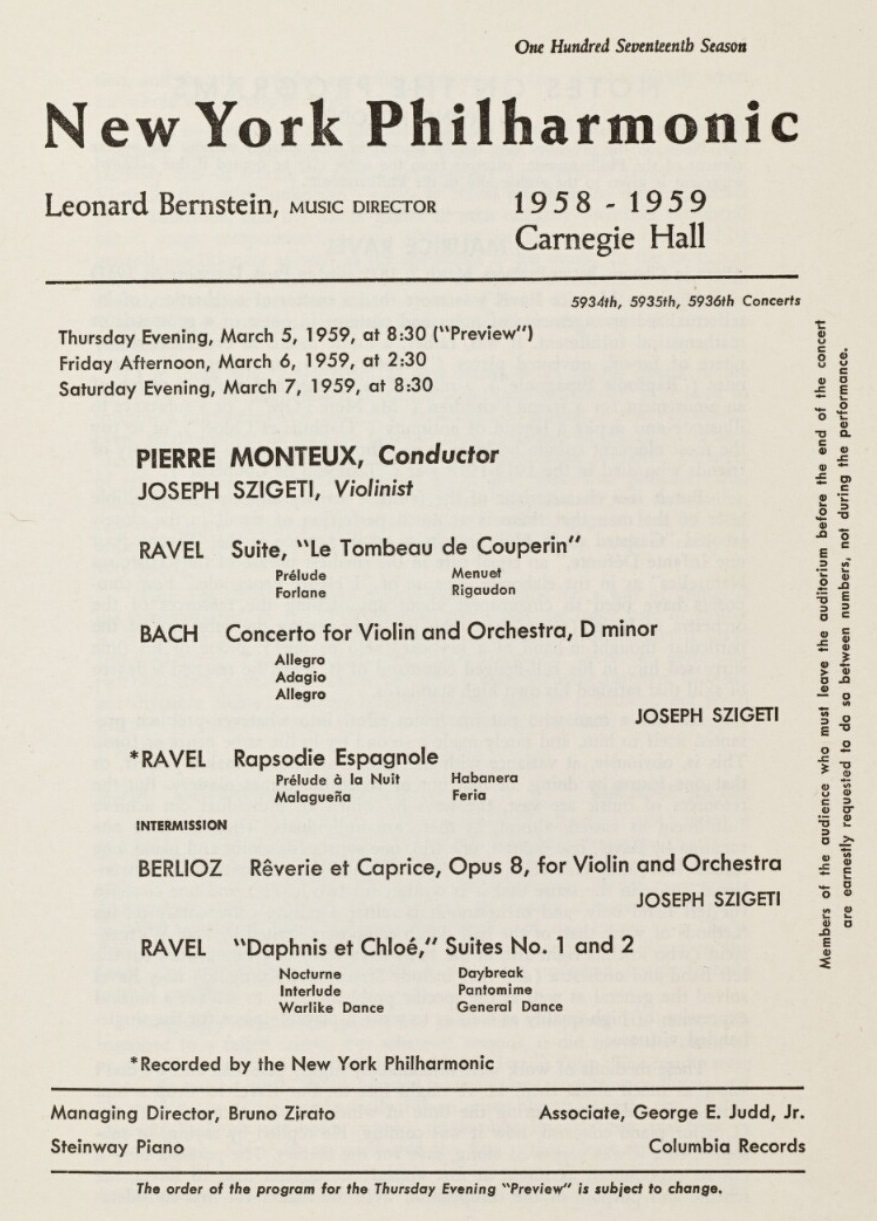

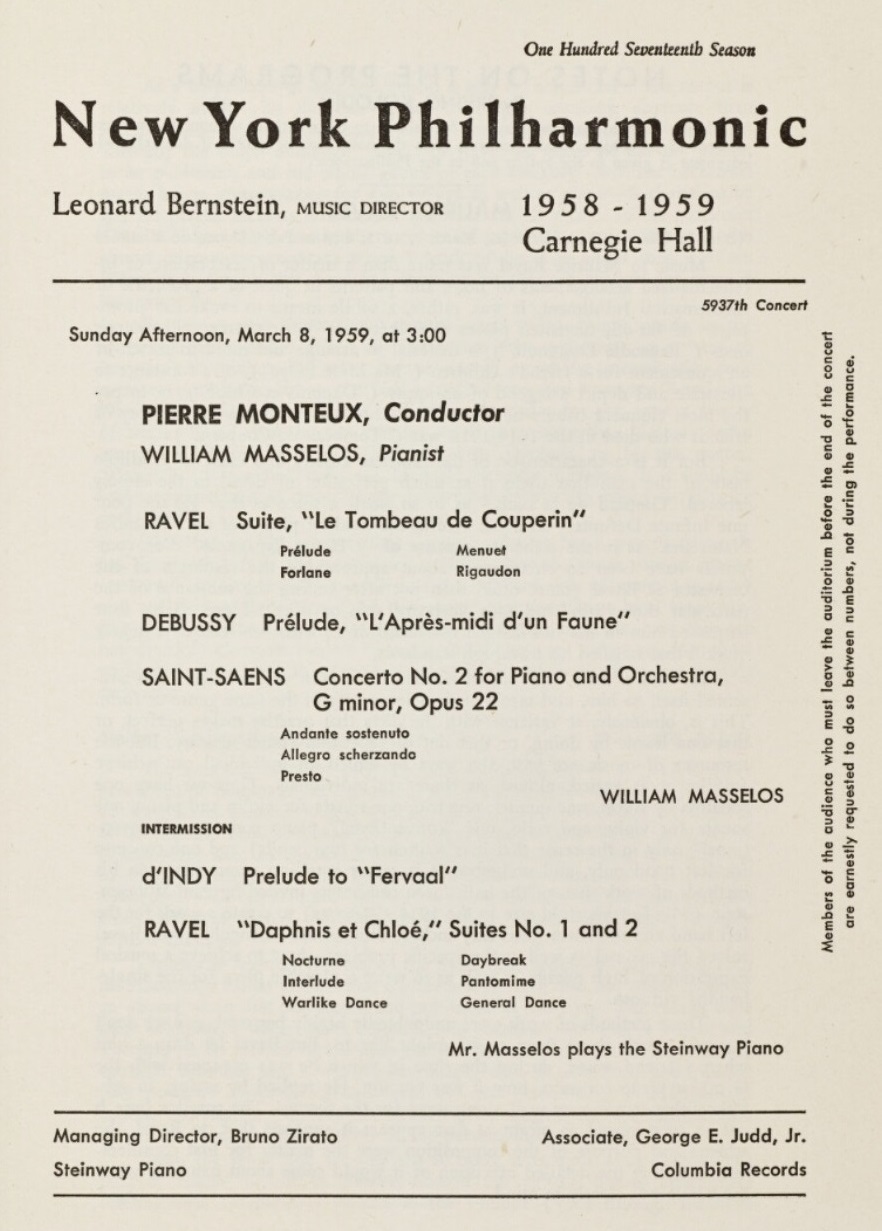

Pierre Monteux – New York Philharmonic (NYPO)

Ravel Tombeau de Couperin – Rapsodie Espagnole – Daphnis & Chloé Suites n°1 (Nocturne – Interlude – Danse guerrière) & 2 (Lever du Jour – Pantomime – Danse Générale)

Carnegie Hall – March 7, 1959

Source Bande /Tape: 2 pistes 19cm/s / 2tracks 7.5 ips

La discographie ravélienne officielle de Pierre Monteux est incomplète et en grande partie tardive (aucun enregistrement pour le disque entre 1947 et 1959). On connaît des enregistrements commerciaux avec l’Orchestre Symphonique de Paris (OSP), le San Francisco SO (SFSO), et le London Symphony Orchestra(LSO) et le 33 tours Ravel de 1964 a été son tout dernier disque. A Boston, il n’a jamais été invité à diriger pendant l’ère Koussevitzky. A partir de 1951, il a été en pratique le premier chef invité de l’orchestre. Mais, au concert comme au disque, Ravel, comme Berlioz, appartenaient en premier lieu à Munch. Quant à l’Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (OSCC), Monteux n’a pas voulu poursuivre sa collaboration avec cet orchestre après sa série Stravinsky de 1956*.

Monteux n’a jamais enregistré le Tombeau de Couperin pour le disque. La présente version avec le NYPO nous paraît supérieure à sa prestation avec le BBC SO (11 Octobre 1961). On peut regretter également de ne pas avoir d’enregistrement des deux Concertos pour piano qu’il avait pourtant à son répertoire.

Monteux a enregistré l’intégrale du ballet Daphnis et Chloé en 1959 avec le LSO et les Chœurs de Covent Garden. A San Francisco, il avait déjà enregistré en 1946 la suite n°1, avec dans l’Interlude, un chœur (non crédité dans les rééditions)**. Ce concert new yorkais avec les Suites n°1 et 2 (sans le chœur) est unique dans sa discographie. L’Interlude est donc donné dans sa version purement orchestrale***, très différente de celle de la version discographique de 1946. On notera également que les deux Suites sont jouées ‘attacca’.

Le concert Ravel avec le NYPO comportait également deux œuvres (Bach et Berlioz) jouées par Joseph Szigeti. A l’époque, sa technique n’était plus du tout ce qu’elle avait été, et le grand violoniste est ici à son désavantage, ce que la critique n’a pas manqué de relever. On ne sait pas si le concert du dimanche 8 mars, dont le programme est différent, a été diffusé, ni si un enregistrement en a été conservé.

* Dans son livre « Putting the Record Straight », John Culshaw écrit à propos des enregistrements réalisés par Decca et l’OSCC : ‘Knappertsbusch n’était pas enclin à forcer les musiciens s’ils n’étaient pas d’humeur à donner le meilleur d’eux-mêmes. Solti s’est battu contre l’orchestre, qui l’a payé de retour. Ils l’ont rendu fou en envoyant des suppléants pour jouer des passages qui avaient déjà été répétés, mais nous avons quand même réussi à terminer son programme avec du temps devant nous… Monteux était économe de mots et de gestes, mais il pouvait obtenir ce qu’il voulait d’un orchestre – même si, après nos premières sessions à Paris, lorsque nous avons enregistré ‘Le Sacre’ et ‘Petrouchka’, il a dit qu’il serait plus heureux si nos futurs projets pouvaient être organisés à Londres, Amsterdam ou Vienne. Même avec un musicien aussi distingué que Monteux à la tête de l’orchestre, la discipline de l’Orchestre du Conservatoire à cette époque était épouvantable, et le système de « remplacement » tout aussi aléatoire qu’il l’avait été avec Solti.

** Le programme de la paire de concerts des 15 et 16 mars 1946, qui ont précédé de peu l’enregistrement avec le San Francisco Symphony Orchestra (SFSO) , mentionne ‘Symphonic Fragments from Daphnis and Chloe First Series’ (Nocturne – Interlude – Warlike Dance) avec le ‘University of California Chorus’, Pr. Edward B. Lawton, Director. Dans le livre de Doris Monteux ‘It’s All in the Music – The Life and Work of Pierre Monteux’, le chœur de l’enregistrement avec le SFSO est identifié comme étant le ‘San Francisco Municipal Chorus’.

*** Monteux a joué la version orchestrale des Suites n°1 et 2 avec le SFSO les 4 et 5 avril 1941, mais en omettant l’Interlude de la Suite n°1. Charles Munch a enregistré les deux Suites à Londres avec l’OSCC le 9 octobre 1946, également en omettant l’Interlude. Wilhelm Furtwängler a laissé un enregistrement des deux Suites avec le BPO (20/21 mars 1944), mais la Suite n°1 commence au milieu de l’Interlude (quelques mesures avant le solo de flûte), et on suppose que l’omission du Nocturne et du début de l’Interlude est due à la perte d’une partie de l’enregistrement.

Ravel par Monteux (enregistrements commerciaux) / Ravel by Monteux (commercial recordings):

-Alborada del gracioso SFSO (December 22, 1947)

-Boléro LSO (Wembley Town Hall – February 22-26, 1964)

-Daphnis & Chloé Intégrale / Complete LSO Ch Covent Garden (Kingsway Hall – April 27 & 28, 1959); Suite n°1 SFSO San Francisco Municipal Chorus (War Memorial Opera House – April 3, 1946)

-Ma Mère l’Oye Intégrale / Complete LSO (Wembley Town Hall – February 22-26, 1964); n°2 Petit Poucet OSP (Salle Pleyel -January 31, 1930)

-Pavane pour une Infante défunte LSO (Kingsway Hall – December 11-13, 1961)

-Rapsodie Espagnole LSO (Kingsway Hall – December 11-13, 1961)

La Valse OSP (January 30, 1930); SFSO (April 21, 1941); LSO (Wembley Town Hall – February 22-26, 1964)

Valses Nobles et Sentimentales SFSO (War Memorial Opera House – April 3, 1946)

Pierre Monteux’s official discography is incomplete and for the most part late (no recording for the disc between 1947 and 1959). We know commercial recordings with the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris (OSP), the San Francisco SO (SFSO) and the London Symphony Orchestra LSO) and the 1964 Ravel LP was his very last record. In Boston, he was never invited to conduct during the Koussevitzky era. From 1951 onwards, he was in practice the orchestra’s first guest conductor. But in concert and on record, Ravel, like Berlioz, belonged first and foremost to Munch. As for the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (OSCC), Monteux did not want to continue his collaboration with this orchestra after his Stravinsky series in 1956*.

Monteux has never made a recording of Ravel’s ‘Tombeau de Couperin’. The present version with the NYPO seems to us superior to his performance with the BBC SO (October 11, 1961). It is also regrettable that there are no recordings of the two Piano Concertos which were, however, part of his repertoire .

Monteux recorded the complete ballet ‘Daphnis et Chloé’ in 1959 with the LSO and the Covent Garden Chorus. In San Francisco, he had already recorded Suite No. 1, with a chorus in the Interlude (uncredited in the re-issues)**. This New York concert with Suites Nos. 1 and 2 (without a chorus) is unique in his discography. The Interlude is thus performed in its purely orchestral version, which is very different from the one of the 1946 recording. It should also be noted that both Suites are played ‘attacca’.

The Ravel concert with the NYPO also included two works (Bach and Berlioz) played by Joseph Szigeti. At the time, his technique was not at all what it had been, and the great violinist is at a disadvantage here, which the critics did not fail to point out. It is not known whether the concert on Sunday March 8, with its different programme, was broadcast, or whether a recording of it has survived.

* In his book ‘Putting he Record Straight’, John Culshaw wrote about the recordings made by Decca and the OSCC: ‘Knappertsbusch was not inclined to force the players if they were not in the mood to give their best. Solti fought the orchestra, and they fought him back. They drove him crazy by sending deputies to play passages which had already been rehearsed, but we stilll managed to finish his programme with time on our hands… Monteux was economical with words and gestures, but he could get just what he wanted out of an orchestra – although, after our first sessions in Paris when we recorded ‘The Rite’ and ‘Petrushka’, he said he would be happier if our future ventures could be arranged in London, Amsterdam or Vienna. Even with so distinguished a musician as Monteux at the helm, the discipline of the Conservatoire Orchestra at that time was appalling, and the ‘substitute’ system just as random as it had been with Solti’.

** The program for the pair of concerts of March 15 and 16, 1946, which shortly preceded the recording with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra (SFSO), mentions ‘Symphonic Fragments from Daphnis and Chloe First Series’ (Nocturne – Interlude – Warlike Dance) with the ‘University of California Chorus’, Pr. Edward B. Lawton, Director. In the book by Doris Monteux ‘It’s All in the Music – The Life and Work of Pierre Monteux ’, the chorus of the SFSO recording is identified as being the ‘San Francisco Municipal Chorus’.

*** Monteux performed the orchestral version of the Suites n° 1 and 2 with the SFSO on April 4 and 5, 1941, but he omitted the Interlude from Suite n°1. Charles Munch recorded both Suites in London with the OSCC on October 9, 1946, also omitting the Interlude. Wilhelm Furtwängler left a recording of both Suites with the BPO (March 20/21, 1944), but Suite no. 1 begins in the middle of the Interlude (a few bars before the flute solo), and it is likely that the omission of the Nocturne and of the beginning of the Interlude is due to the loss of part of the recording.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

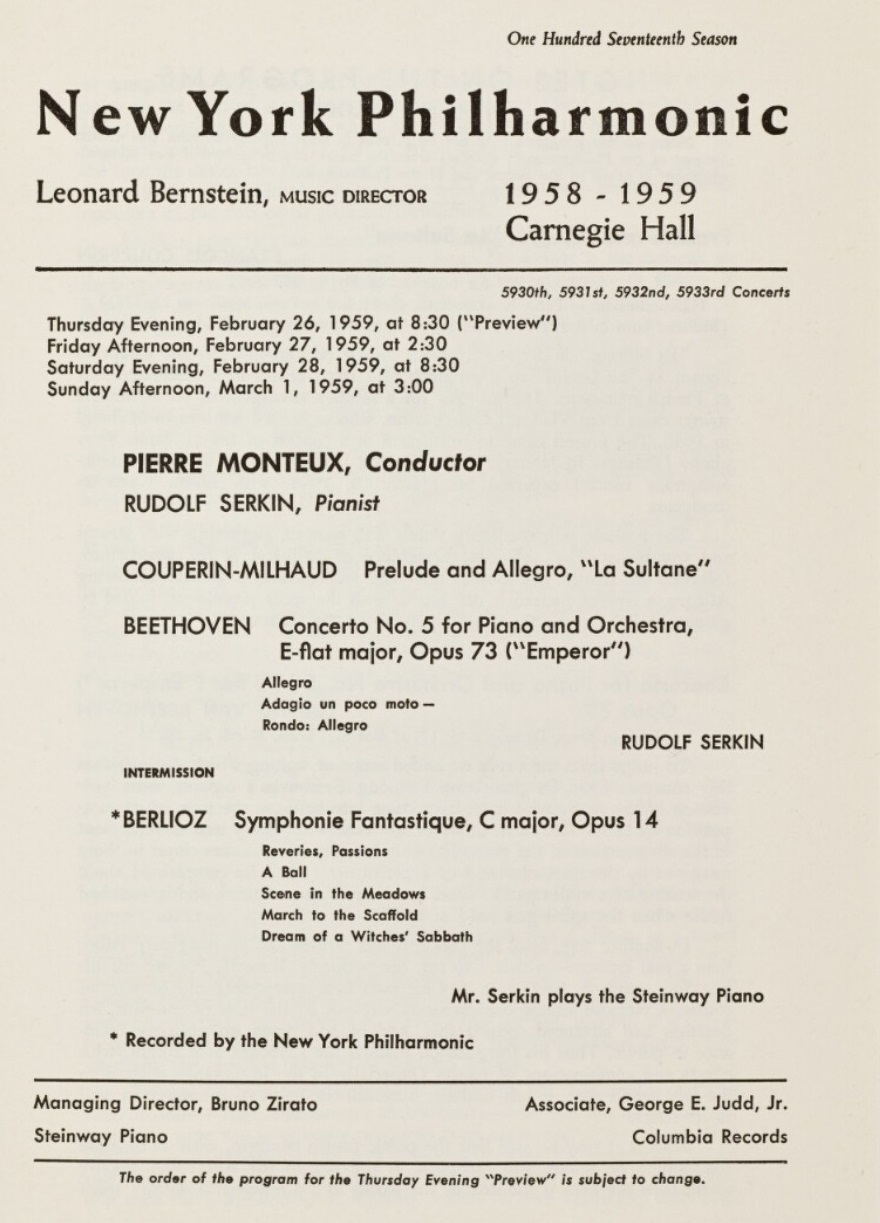

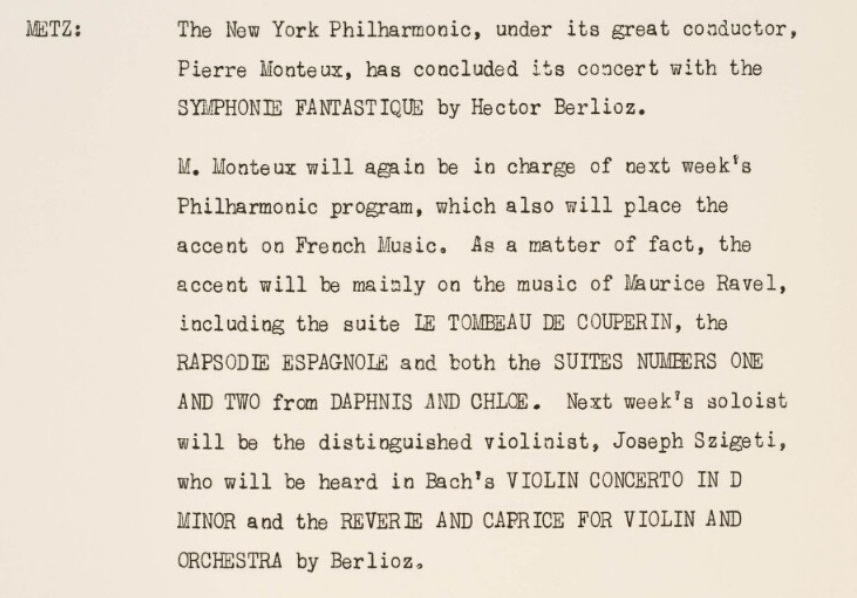

Pierre Monteux – New York Philharmonic (NYPO)

Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique

Carnegie Hall – February 28, 1959

Source Bande /Tape: 2 pistes 19cm/s / 2tracks 7.5 ips

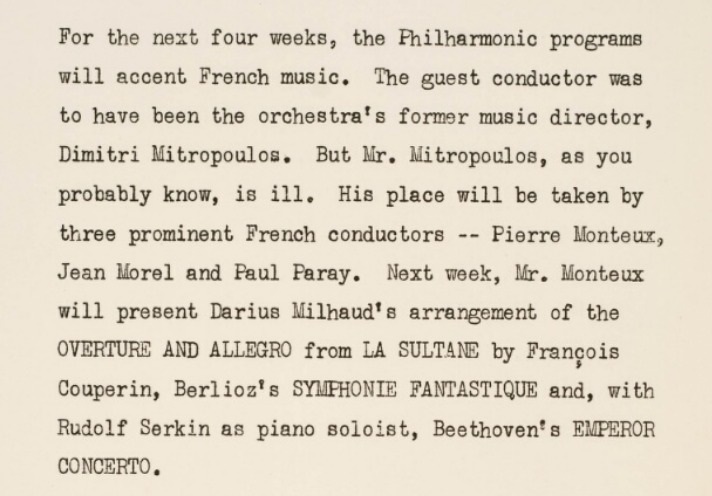

Entre le 27 février et le 22 mars 1959, Dimitri Mitropoulos devait diriger comme chef invité quatre semaines de concerts avec le NYPO, avec des programmes consacrés en majorité à la musique française. Le 23 janvier, il a subi une deuxième attaque cardiaque qui l’a obligé à interrompre son activité pour de longs mois. Les programmes que Mitropoulos devait diriger étaient les suivants:

26, 27 & 28 Février; 1er Mars: ROUSSEL Symphonie n°3; SCHMITT La Tragédie de Salomé – BEETHOVEN Concerto n°5 avec Rudolf SERKIN

5, 6 & 7 Mars: BARRAUD extraits du Ballet ‘L’ Astrologue dans le Puits’; BERLIOZ Rêverie et Caprice avec Josef SZIGETI; EGK Geigenmusik avec Josef SZIGETI – SAINT-SAËNS Symphonie n°3

8 Mars: LALO Le Roi d’Ys Ouverture; SAINT-SAËNS Concerto n°2 William MASSELOS – CHAUSSON Symphonie

12, 13, 14 & 15 Mars: DEBUSSY Pelléas et Mélisande (version abrégée) avec Phyllis CURTIN (Mélisande), Nicolaï GEDDA (Pelléas), Martial SINGHER (Golaud), Regina RESNIK (Geneviève), Kenneth SMITH (Arkel)

19, 20, 21 & 22 Mars: BERLIOZ Le Corsaire, Ouverture – Cinq extraits de Roméo et Juliette – Carnaval Romain, Ouverture

Jean Morel a assuré les concerts DEBUSSY (Pelléas et Mélisande) et Paul Paray a dirigé lors de la quatrième semaine un programme différent tout en reprenant la Symphonie n°3 de Saint-Saëns.

Les deux premières semaines ont été confiées à Pierre Monteux (le contrat a été signé le 2 février), lequel a certes dirigé de la musique française, mais d’un répertoire plus limité (Berlioz et Ravel), c’est-à-dire une occasion de donner en concert deux compositeurs qu’il n’a pu que très peu diriger à Boston depuis son retour en 1951 comme chef invité du BSO. Les deux concerts enregistrés dont nous disposons sont ceux du samedi soir et non, comme c’était en général la cas, du dimanche après-midi.

Quoi qu’il en soit, il est très intéressant de disposer de cette très belle ‘Fantastique’ en public, car, une version avec le BSO n’ayant pas été possible, les deux derniers enregistrements de l’œuvre par Monteux sont pour l’un controversé (WPO 1958), alors que l’autre (NDR 1964) n’est pas du tout réussi. Si les deux versions antérieures avec le SFSO (1945 et 1950) sont magnifiques, la prise de son en est plutôt décevante. D’ailleurs, de tous ses enregistrements commerciaux, Monteux préférait le tout premier, de 1930, avec l’OSP (Orchestre Symphonique de Paris), de surcroît remarquablement bien enregistré pour l’époque.

Le programme est présenté par Stuart Metz qui remplace Jim Fassett, en déplacement à l’étranger.

Between 27 February and 22 March 1959, Dimitri Mitropoulos was to conduct as guest conductor four weeks of concerts with the NYPO, with programmes devoted mainly to French music. On 23 January he suffered a second heart attack, forcing him to interrupt his activities for several months. The programmes Mitropoulos was due to conduct were as follows:

February 26, 27 & 28; March 1: ROUSSEL Symphony n°3; SCHMITT ‘La Tragédie de Salomé’ – BEETHOVEN Concerto n°5 with Rudolf SERKIN

March 5, 6 & 7: BARRAUD excerpts from the Ballet ‘L’ Astrologue dans le Puits’; BERLIOZ ‘Rêverie et Caprice’ with Josef SZIGETI; EGK Geigenmusik with Josef SZIGETI – SAINT-SAËNS Symphony n°3

March 8: LALO ‘Le Roi d’Ys’ Overture; SAINT-SAËNS Concerto n°2 William MASSELOS – CHAUSSON Symphony

March 12, 13, 14 & 15: DEBUSSY Pelléas et Mélisande (abridged version) with Phyllis CURTIN (Mélisande), Nicolaï GEDDA (Pelléas), Martial SINGHER (Golaud), Regina RESNIK (Geneviève), Kenneth SMITH (Arkel)

March 19, 20, 21 & 22: BERLIOZ ‘Le Corsaire’, Overture – Five excerpts from ‘Roméo et Juliette’ – ‘Carnaval Romain’, Overture

Jean Morel conducted the DEBUSSY concerts (‘Pelléas et Mélisande’), and Paul Paray conducted a different programme in the fourth week, taking up Saint-Saëns’ Symphony No. 3.

The first two weeks were entrusted to Pierre Monteux (the contract was signed on 2 February), who for sure conducted French music, but from a more limited repertoire (Berlioz and Ravel), namely an opportunity to perform two composers he could only marginally conduct in Boston since his return in 1951 as guest conductor of the BSO. The two recorded concerts we have are those on Saturday evening, and not, as usual, Sunday afternoon.

Be that as it may, it is very interesting to have this very fine ‘Fantastique’ performed live, since, a version with the BSO having been impossible, Monteux’s last two recordings of the work were for the first one (WPO 1958), controversial , while the other (NDR 1964) was not at all successful. While the two earlier versions with the SFSO (1945 and 1950) are magnificent, the recorded sound is rather disappointing. In fact, of all his commercial recordings, Monteux preferred the very first, from 1930, with the OSP (Orchestre Symphonique de Paris), which was also remarkably well recorded for its time.

The programme is presented by Stuart Metz, who replaces Jim Fassett, who was travelling abroad.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

27, 28, 30 August & 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 27, 30 September 1942

17, 21, 23, 25, 31 July 1943

A tribute to mark the centenary of her birth

Version Française: cliquer ICI

Maria Callas sang the role of Floria Tosca throughout her stage career, from 1942 to 1965. At the Greek National Opera, which was founded in 1939, she was able to benefit from exceptional working conditions to present this work in a new production when she was only 18, at a time when Greece was undergoing extremely harsh occupation conditions. Nicholas Petsalis-Diomidis’s indispensable book ‘The Unknown Callas – The Greek Years’ describes in detail how this new presentation of Tosca was staged, how Callas’s acting and singing fascinated from the outset, and how the production became a kind of benchmark for herself and for many other directors, so that twenty years later, and even more, it continued to influence new productions.

In a 1978 interview, actress Edwige Feuillère declared: ‘I admired Maria Callas at the Paris Opera in Tosca. She was extraordinarily beautiful and musical, but above all, for me as an actress, she was doing something extraordinary. I was at the Opera’s basket, and in the second act, where she is with Scarpia, I saw the precise moment when the idea of murder was germinating in her mind: you could see her eye stop on the knife on the table, the glass she was holding to her lips stop mid-stroke, and from a distance, you knew that this woman was going to kill Scarpia. It’s a marvellous piece of interpretative work, and it touched me deeply. For me, there was magic in it. Her vibrations were magical, there was a kind of exoticism in her timbre. All the beauty in her person was acquired beauty and elegance, and on top of that, there was all the incessant work on incomparable gifts, and the sum of all that is genius. This is a woman who, during her short trajectory, thought of nothing but recreating herself every day at every moment.‘

As Edwige Feuillère has pointed out, making the most of genius requires ceaseless work, and what is at first sight fascinating about Callas is that by 1942, she had already defined the exacting working methods that enabled her to do so, and which she would apply throughout her career. What’s even more fascinating is that, at such a young age, she was able to build a memorable interpretation of the character.

She had begun studying Tosca in 1938 with her teacher at the time, Maria Trivella, associate professor at the Athens Conservatory. At the instigation of tenor Ulysses Lappas, and after a favorable opinion from Elvira de Hidalgo, Maria Kalogeropoulou was officially chosen by the General Secretary of the National Theater Angelos Terzakis on July 10, 1942 to sing the role of Floria Tosca in a series of eighteen performances of Tosca under the direction of conductor Sotos Vassiliadis with stage director Dino Yannopoulos. The performances which were sold out, took place between August 27 and September 30, 1942, at the open-air Summer Theater in Athens’ Klafthmonos Square, a small venue with a modestly sized stage, with a premiere on August 27 for the version sung in Greek in Angelos Terzakis‘s translation, and on September 8 for the version sung in Italian (3 performances). Among the main characters, she was the only one to sing in both languages, and therefore had to learn the work and ensure all rehearsals in Greek and Italian. Mario was sung in Greek by Antonis Delendas and in Italian by Loudovikos Kourousopoulos. Baron Scarpia was sung in Greek by Titos Xirellis and Spyros Kalogeras (from September 24), and in Italian by Lakis Vassilakis. A revival with the same cast took place in 1943 for five performances in Greek ( July 17, 21, 23, 25 and 31 ).

Summer Theater at Klafthmonos Square (Athens)

Piano rehearsals for Tosca began in the hall of the National Theatre. According to Loudovikos Kourousopoulos, from the very first rehearsals, Callas was exceptional in her musicality and virtuosity. The two casts rehearsed alternately in Greek and Italian, and she had to be present at all times. When rehearsals with orchestra began at the theater in Klafthmonos Square, she always sang in full voice, without saving herself, as she would continue to do throughout her career. As her short-sightedness prevented her from seeing the conductor, she also attended rehearsals reserved for the orchestra alone, so as not to have to depend on the conductor’s gestures. In addition, Callas also studied the role in private rehearsals with conductor Sotos Vassiliadis and baritone Titos Xirellis, who was a renowned singer and composer. In particular, the latter taught her how to play the difficult scene in Act II between Scarpia and Tosca, which she would benefit from in all subsequent performances throughout her career.

At the premiere on Thursday August 27, 1942, the audience quickly realized that Maria Kalogeropoulou was someone to be noticed. According to Dino Yannopoulos, ‘When she came on stage, it was as if she took the audience by the scruff of the neck and said: Now, hear me!, I’ve something to say’. Antonis Kalaidzakis, a member of the chorus that night, says: ‘I remember that ‘Mario, Mario, Mario!’. It sent a shiver down your spine! It was a cry that came straight from the heart. That voice of hers was strange, there was a natural sob in it that projected you straight into an atmosphere of drama. The sound was a bit throaty, but attractively throaty, like the sound of a string instrument when not played absolutely true. It became crystal clear only on the high notes’.

After the aria ‘Vissi d’arte’ which she had to encore at each performance, the scene where she stabs Scarpia was impressive thanks to the ‘business’ devised by Yannopoulos and brilliantly performed by Maria. As Scarpia sat at his desk writing the safe-conduct Tosca has asked of him, she backed diagonally downstage toward the table. Stefanos Ciotakis, another member of the chorus, recalled: ‘On the table was the dagger, with the hilt toward her. She moved closer and closer to the table, walking rather unsteadily and we, knowing she could’nt see, were on tenterhooks. Would she put her hand on it or..?. But she, having measured her paces to perfection, arrived at the table and picked up the dagger with absolute precison, without even turning her head. That really froze the blood in our veins! ‘

Andonis Kalaidzakis remembers with emotion how, after Scarpia’s stabbing, Maria let the dagger drop from her hand and placed a candle on either side of the dead tyrant. The audience felt a thrill of excitement when Maria extracted the note clutched in the dead Scarpia’s hand. And then, she made her exit with another clever piece of staging by Dino Yannopoulos: walking at stage right, with her ermine cloak thrown over her shoulder and trailing on the floor, Maria turned round to look back at the dead Scarpia, while the curtain was drawn across from stage left to bring the scene to an end. Luschino Visconti acknowledged that he had admired that ingenious touch. Franco Zeffirelli was inspired by it, as was Benoit Jacquot much later (2001) in his film.

Her voice already had its essential properties. For the tenor Loudovikos Kourousoupoulos who was Mario in the three performances sung in Italian , ‘if you heard her sing without seeing her, you would think it was three different people singing. She had difficulties with the transitions from one register to another. When she hit a high note cleanly her voice didn’t wobble, but on an upward portamento it did. However, she had such a big vocal range and such warmth of tone, and above all her acting was so good, that those things were forgotten. The whole effect was so vibrantly alive that it made you jump out of your seat.’ This is confirmed by Nikos Papachristos, who was in the chorus: ‘We were baffled and taken aback by her voice. It had so many different tone colors that it lacked homogeneity: a high voice, a middle voice, and a low voice, all quite distinct. But there was a tremendous fluency throughout, and she acted so naturally on stage that you overlooked her vocal flaws.’

with Loudovikos Kourousopoulos

On Herbert Graf’s recommendation, Dino Yannopoulos was hired as principal director at the MET and remained there between 1946 and 1967. There, Callas met him again for his stage directions of Tosca (in 1956, 1958 and 1965) and of Norma in 1956. The excerpts from the end of Act II filmed during the Ed Sullivan Show on November 25, 1956 (dir: Dimitri Mitropoulos with George London, Scarpia) give us an idea of his staging, with particularly, at the very end, Callas’ famous exit with her cloak trailing on the floor.

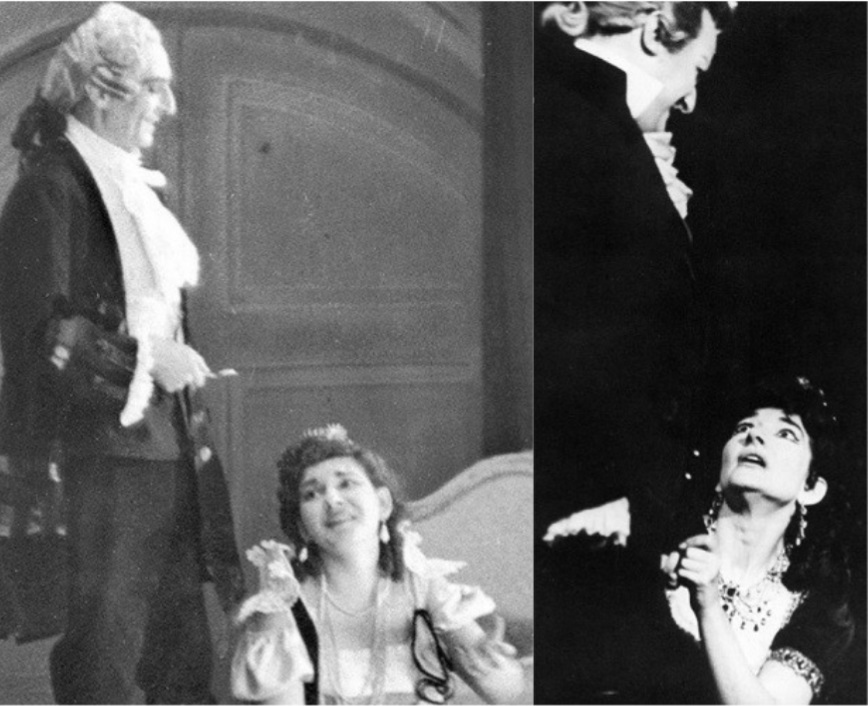

The comparative photographs below, taken on stage during the rehearsals of Act II in 1942 in Athens with stage director Dino Yannopoulos, and in 1964 in London (Covent Garden) under the direction of Franco Zeffirelli, show astonishing visual similarities between the two productions taken at the very beginning (in 1942, she was not yet 19) and near the end of Maria Callas’ stage career. Her very last public performance of an opera was Tosca at Covent Garden on July 5, 1965.

On the pictures below: Left: Athens Opera 1942; Right: London Covent Garden 1964

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

______

Act II Tosca/Mario – Left: with Antonis Delendas ; Right: with Renato Cioni

______

Act II – ‘Vissi d’arte’

______

Act II Tosca/Scarpia – Left: with Titos Xirellis ; Right: with Tito Gobbi

N.B. Some sources claim that Maria Callas sang Tosca in Athens in July 1941 to replace an ailing singer. This information is incorrect. There were no performances of Tosca at the National Theater in 1941. It was only in 1942, with the new production, that Tosca began to be performed there.