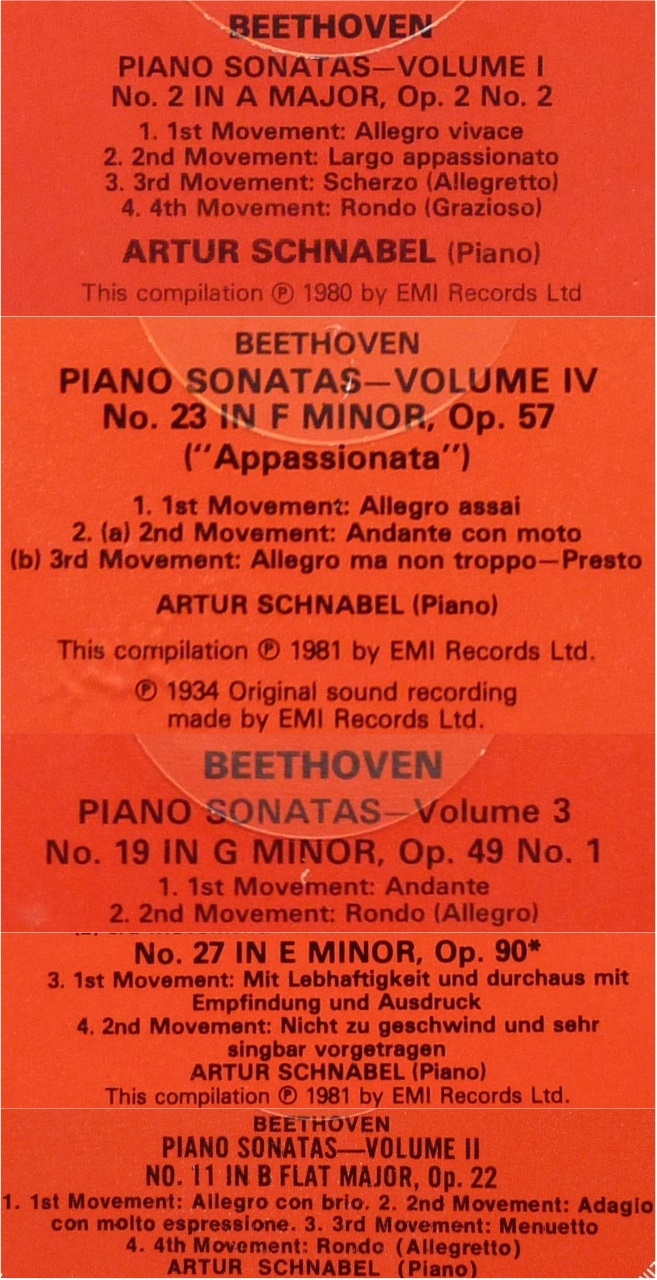

Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates – III/VII -Sonates n°2 Op.2 n°2 – n°23 Op.57 – n°19 Op.49 n°1 – n°27 Op.90 & n°11 Op.22

Sonate n°2 Op.2 n°2: 9 Avril 1933

Sonate n°23 Op.57: 11 Avril 1933

Sonate n°19 Op.49 n°1: 19 Novembre 1932

Sonate n°27 Op.90: 21 Janvier & 3 Février 1932

Sonate n°11 Op.22: 12 & 13 Avril 1933

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n° 3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le troisième programme de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comportait les cinq sonates mentionnées ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Pour le troisième programme de l’intégrale donnée par Schnabel à Carnegie Hall en 1936, Howard Taubman souligne que la simplicité et la ré-utilisation de moyens mis en oeuvre par d’autres compositeurs dans la sonate en la majeur Op.2 n°2 mettent en valeur l’audace et l’originalité de la pensée de Beethoven dans l’ « Appassionata » qui pour une fois n’est pas « interprétée », Schnabel semblant laisser Beethoven parler pour lui-même en libérant toute sa puissance, tout en maintenant l’oeuvre dans les limites du piano. « Il n’a pas donné l’impression que cultivent certains virtuoses qu’il pourrait obtenir on ne sait quels prodiges avec un instrument de plus grande ampleur. En jouant l’une après l’autre les sonates en sol mineur (Op.49 n°1) et en mi mineur (Op.90), Schnabel a montré qu’elles étaient plus proches que le simple fait d’avoir le même compositeur avec des ressemblances et des différences, la première étant calme, romantique et directe, et la deuxième, claire profonde et pénétrante. Et enfin, la sonate en si bémol majeur (Op.22), moins exigeante pour l’auditeur, terminait la courbe claire et ample du programme ».

Il est intéressant à ce point pour approfondir cette analyse du style d’interprétation d’Artur Schnabel par les critiques musicaux Olin Downes et Howard Taubman de se référer au magnifique texte de Claudio Arrau publié en 1952 sous le titre « Artur Schnabel Servant of the Music » (« Artur Schnabel Serviteur de la Musique ») et qui est pour l’essentiel consacré aux Sonates de Beethoven et à son message humaniste:

« Dans mon souvenir de la manière dont Schnabel jouait Beethoven, deux choses me viennent particulièrement en mémoire: sa compréhension du caractère global de chaque sonate et son traitement admirable des mouvements lents. Avec toutes les sonates, depuis la toute première—dans laquelle Beethoven est déjà Beethoven et aussi un maître, et qui de ce fait est entièrement achevée à la fois par sa forme et sa construction et par son caractère essentiel — jusqu’à l’ultime Op. 111, où Beethoven est le prophète qui transcende tout le combat humain, Schnabel est devenu lui-même un prophète par sa compréhension des détails des parties qui les constituent et de la somme totale de cette littérature colossale.

A une époque où jouer vite semblait souvent être le seul but de la virtuosité pianistique, Schnabel n’en avait cure et il montrait son courage en jouant vraiment lentement les mouvements lents. Renforcé par sa conviction et par sa concentration, il les jouait plus lentement que quiconque ne l’avait jamais imaginé possible. Et sa manière de ralentir encore plus à la fin de tels mouvements était absolument inoubliable, un ralentissement qui créait une atmosphère dramatique et une tension qui étaient à la fois impressionnantes et uniques. C’était la preuve d’un profond calme intérieur que la plupart des musiciens n’atteignent que tard dans leur vie, voire jamais, mais qu’il possédait à un rare degré depuis le début. . . .

Son interprétation de l’Opus 54 (sonate n°22) montre qu’il ne suivait pas aveuglément sa propre édition et ses indications, mais se donnait la liberté de suivre l’inspiration du moment. Il maintenait à un rare degré à la fois un équilibre des moyens pour faire les choses comme il les concevait et un équilibre entre l’intellect et l’émotion intuitive. Beaucoup d’artistes ont soit l’un, soit l’autre de ces dons. Mais chez Schnabel il y avait une synthèse remarquable de savoir, d’intelligence, d’intuition, d’émotion et de moyens techniques. L’importance en tant qu’artiste de Schnabel vient de l’importance du message de la musique de Beethoven. Avec les trente deux sonates, Beethoven a créé tout un univers. Dans leur globalité, elles forment une immense épopée du combat de l’humanité et de sa souffrance et de la victoire ultime de l’esprit. Fait unique, Schnabel était un homme et un artiste à la hauteur de toutes les exigences de cette stupéfiante effusion de génie.

Dans les dernières sonates, Beethoven a développé un langage pour les initiés, un langage dont le caractère symbolique et ésotérique n’a jamais été surpassé dans aucune autre œuvre d’art antérieure ou postérieure. C’est parce que Schnabel était un des rares initiés qui comprenaient et parlaient ce langage qu’il était capable de rendre le Beethoven de cette période plus proche de la compréhension contemporaine. Il n’y a pas de plus grande réalisation qu’un artiste puisse accomplir. »

Claudio Arrau

____________

Artur Schnabel’s third program of the complete Beethoven sonatas was comprised of the above mentioned five sonates, two of which being played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

For the third program of the complete performance given by Schnabel at Carnegie Hall in 1936, Howard Taubman underlines that the simplicity and untroubled iteration of other composer’s devices of the early sonata from the Op.2 series (Op.2 N°2) were ideal foils for the audacity and originality of Beethoven’s thinking in the « Appassionata » for which Mr. Schnabel seemed to let Beethoven speak for himself with all its surging power, while keeping the work within the piano’s limitations. « He did not give the impressions cultivated by some virtuosos what wonders they could work with an instrument with greater scope. The G minor (Op.49 n°1) and E minor (Op.90) sonatas placed besides each other, appear to have a closer relationship than the obvious one of stemming from the same progenitor. Mr. Schnabel indicated their closeness and disparity – the former: cool, romantic, direct; the latter: clear, profound, penetrating. And finally the B flat major sonata (Op.22), less exacting in its demand on the listener and providing the end of the program’s clean, sweeping curve ».

It is interesting at this point to deepen this analysis of Artur Schnabel’s style by music critics Olin Downes and Howard Taubman, to revert to the magnificent text by Claudio Arrau published in 1952 under the title « Artur Schnabel Servant of the Music » and essentially dealing with the Beethoven Sonatas and their humanist message:

« Remembering how Schnabel played Beethoven, two things particularly stand out in memory: his grasp of the whole character of every sonata and his divine way with the slow movements. With all the sonatas, from the very first one—in which Beethoven is already Beethoven and a master, and which is therefore entirely definite both in shape and construction and in essential character—to the final Op. 111, where Beethoven is the seer transcending all human struggle, Schnabel became a seer himself in his grasp of the component details and the sum total of this colossal literature.

In a period when playing fast often seemed to be the sole goal of piano virtuosity, Schnabel paid no heed and showed his courage by making the slow movements really slow. Strengthened by conviction and concentration, he played them slower than anyone else had even imagined to be possible. Absolutely unforgettable was his way of slowing down still more at the end of such movements, a slowing-down that created a dramatic atmosphere and tension that were both impressive and unique. This was evidence of a deep, inner repose that most musicians attain only latc in life, if ever, but that he possessed to a rare degree from the beginning. . . .

His performance of Opus 54 shows that he did not follow his own edition and markings slavishly, but gave himself freedom to follow the inspiration of the moment. To a rare degree he maintained both a balance of the means required to do things as he conceived them and a balance between intellect and intuitive emotion. Many artists have one gift or the other. But in Schnabel there was a remarkable synthesis of knowledge, intelligence, intuition,emotion and technical means. Schnabel’s importance as an artist stems from the importance of the message of Beethoven’s music. In the thirty-two sonatas Beethoven created a whole cosmos. In their totality, they form an immense epic of man’s struggle and suffering and ultimate victory of the spirit. Schnabel, uniquely, was man and artist enough to meet all the demands of this staggering outpouring of genius.

In these last sonatas Beethoven developed a language for the initiated, a language of a symbolic and esoteric character never more strongly pronounced in any works of art before or since. Because Schnabel was one of the few initiated who understood and spoke this language he was able to bring the Beethoven of this period nearer to contemporary comprehension. No greater realization could come to any artist. »

2 réponses sur « Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates – III/VII -Sonates n°2 Op.2 n°2 – n°23 Op.57 – n°19 Op.49 n°1 – n°27 Op.90 & n°11 Op.22 »

HD/Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZEzCHZrK1E1MQ4v5uWA6QYfx7mKJ0OlYAy

Format CD (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZOzCHZU2dY86z5GN5wnMHb9jxmwbCJs8zk

Thank you very much! It is a real privilege to have your beautifully transfered high res remasters of the best sources (the HMV Treasury LPs) available.