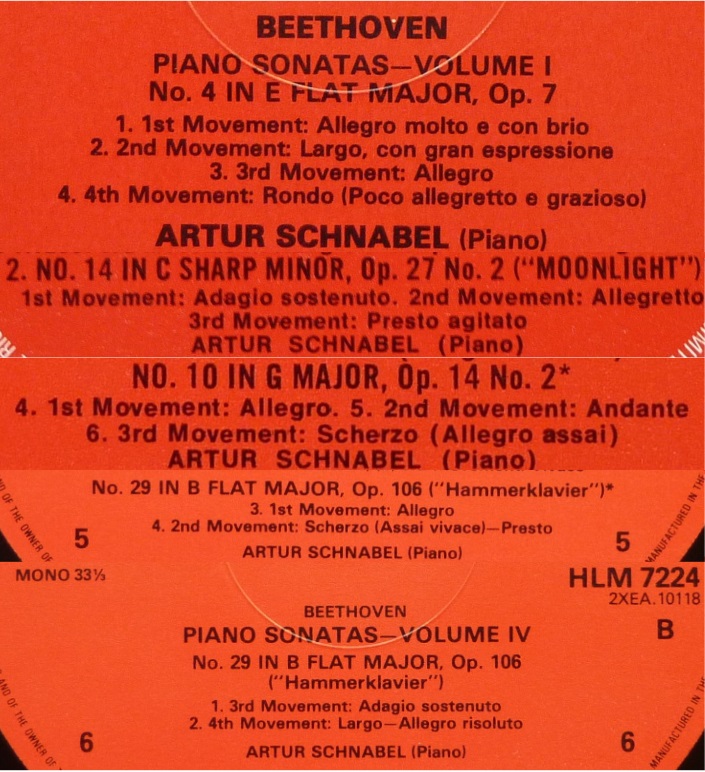

Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates – V/VII – Sonates n°4 Op.7 – n°14 Op.27 n°2 – n°10 Op.14 n°2 – n°29 Op.106

Sonate n°4 Op.7: 11 Novembre 1935; 15 Janvier1937 (face 2)

Sonate n°14 Op.27 n°2: 10& 11 Avril 1933

Sonate n°10 Op.14 n°2: 23 Avril 1934

Sonate n°29 Op.106 « Hammerklavier »: 3 & 4 Novembre 1935

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Les trois derniers récitals de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel en formaient le point culminant. En effet, ils se terminaient chacun par une des dernières sonates respectivement n°29 Op.106, n°30 Op.109 et enfin n°32 Op.111. La sonate n°31 Op.110 a quant à elle été jouée au cours du premier récital.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le cinquième programme comportait les quatre sonates mentionnées ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert, alors qu’il aurait semblé plus logique de ne jouer que la sonate n°29 Op.106 en deuxième partie. On voit ici le souci de Schnabel d’individualiser au maximum chaque sonate en jouant en début de seconde partie la sonate n°10 Op.14 n°2 dont Eric Blom caractérisait le thème du premier mouvement en disant qu’il pourrait se chanter avec les paroles « O, what a happy day », tout en restant pour la monumentale sonate n°29 Op.106 dans le cadre stylistique qu’il s’était fixé: à un critique qui trouvait que son enregistrement de cette œuvre n’était pas du « grand piano », il a répliqué « it’s big in concept, not in sound » (c’est grand par le concept, et non par le son). Une grande leçon!

Comme les critiques de disque l’ont remarqué, l’Op.106 pose le problème des limites techniques de Schnabel à l’époque de l’enregistrement, d’autant plus qu’il se conforme aux indications métronomiques spécifiées par Beethoven (c’est la seule sonate pour laquelle le compositeur en a fourni). Claudio Arrau a dit que sa technique était parfaite jusqu’à l’arrivée au pouvoir des nazis, qui l’a contraint brutalement à quitter définitivement l’Allemagne, mais que c’est ensuite que les difficultés techniques sont apparues, de même que des trous de mémoire. Si ici, le début du premier mouvement est plutôt chaotique, il semble aussi qu’à la base, il y ait un choix conceptuel aussi génial que délibéré, comme si le discours, incroyablement tendu, émergeait du chaos pour s’organiser progressivement. Schnabel est celui qui ose! D’ailleurs, pour cette série d’enregistrements de novembre 1935, certaines des faces ont été refaites en janvier 1937 pour les sonates n°4 Op.7 & 16 Op.31 n°1, mais pas pour l’Op.106.

Peu après cet enregistrement, Schnabel a joué deux fois cette sonate, tout d’abord à Vienne au Konzerthaus (16 décembre 1935), puis à New-York le 12 avril 1936, le cinquième récital de son intégrale, et pour ces deux exécutions, les critiques ne mentionnent pas de problèmes techniques.

Pour le concert viennois, Herbert Peyser fait état d’un monumental récital Beethoven culminant dans une exécution de l’ ‘Hammerklavier’ apte à pulvériser quiconque aurait proféré des mots irrespectueux envers cet Opus prométhéen, notamment son apothéose fuguée.

Pour le cinquième programme de l’intégrale donnée par Schnabel à Carnegie Hall en 1936, Howard Taubman mentionne que le couronnement de ce récital était l’interprétation de la sonate ‘Hammerklavier’ Op.106 (n°29), une éloquente re-création d’une oeuvre immense, et que les sonates joués avant semblaient pâles en comparaison. ‘L’ ‘Hammerklavier’ se situe sur le même plan que les pages gigantesques des symphonies de Beethoven. Même pour des oreilles modernes, elle sonne audacieuse de par son concept et d’une imagination brillante quant à son exécution, et plus d’un siècle s’est écoulé sans que son originalité prophétique en soit diminuée. Elle demande pour lui donner vie un pianiste qui maîtrise une fusion magistrale de la tête, du cœur et des mains, et Mr. Schnabel était hier soir un tel artiste. Il y avait de la passion et de la puissance dans les deux premiers mouvements de la sonate, et l’interminablement difficile section finale a été rendue avec une maîtrise achevée. Mais c’est dans l’immense mouvement lent – séraphique dans son exaltation et poignant par sa compassion interrogative – que Mr. Schnabel a joué de la manière la plus profondément émouvante de la soirée. Il n’y a à l’étranger pas beaucoup de pianistes capables de rendre justice à ce mouvement. Mr. Schnabel était en forme hier soir et son interprétation des trois sonates précédentes était marquée par une attention caractéristique à la fois pour les détails et pour la pleine conduite du discours d’une œuvre. La sonate en do dièse mineur (n°14 Op.27 n°2), depuis des années la préférée des broyeurs d’ivoire, y trouvait une nouvelle vitalité.’

The last three recitals were the climax of Artur Schnabel’s complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 sonata. Indeed, each of them ended with one of the last sonatas respectively n°29 Op.106, n°30 Op.109 and finally n°32 Op.111. Sonata n°31 Op.110 was played separately at the first recital.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The fifth program was comprised of the four above mentioned sonatas, the first two of which being played before the intermission, whereas it would have been more logical to play only the sonata n°29 Op.106 at the second part of the recital. This reflects Schnabel’s concern to individualize each sonata to the utmost by playing at the beginning of the second part the sonata n°10 Op.14 n°2 of which Eric Blom caracterized the thema of the first movement by saying it could be sung to the words « O, what a happy day », while remaining for the monumental sonata n°29 Op.106 in the stylistic frame he decided: to a critic objecting that his recording of this work was not « great piano », he replied « it’s big in concept, not in sound ». A great lesson!

As music critics have noticed, Op.106 poses the problem of Schnabel’s technical limits at the time of the recording, all the more so since he applies Beethoven’s metronomic markings (it is the only sonata for which the composer provided them). Claudio Arrau said that his technique was flawless until the nazis came to power, which brutally obliged him to leave Germany, but thereafter, technical difficulties started and also memory mistakes. If here the beginning of the first movement is rather chaotic, it seems also that basically this was a chosen concept as full of genius as it was deliberate, as if the incredibly tense musical flow emerged from chaos to organize itself progressively. Schnabel is the one who dares! Indeed for this series of recordings of November 1935, a few sides were re-recorded in January 1937 for the sonatas n°4 Op.7 & 16 Op.31 n°1 but not for Op.106!

Shortly after this recording, Schnabel performed this sonata twice, firstly at the Vienna Konzerthaus (16 December 1935), then on 12 April 1936, the fifth recital of his complete performance of the ’32s’, and in both cases, music critics do not mention at all technical problems.

For the Viennese concert, Herbert Peyser speaks of a monumental Beethoven recital culminating in a performance of the ‘Hammerklavier’ which must have pulverized any one who ever spoke a disrespectful word of this Promethean Opus, particularly of his fugal apotheosis.

For the fifth program of the complete performance given by Schnabel at Carnegie Hall in 1936, Howard Taubman mentions that the pinnacle of the recital was the performance of the B flat major Sonata Op.106 known as the ‘Hammerklavier’, an eloquent recreation of an immense work, and that the sonatas that had gone before seemed pale in comparison. ‘The ‘Hammerklavier’ is on the plane of the gigantic pages of Beethoven’s symphonies. Even to modern ears, it sounds audacious in design and brilliantly imaginative in execution; more than a century of currency has not dimmed its prophetic originality. It requires a pianist who commands a superb fusion of head, heart and hands to bring this sonata to life, and Mr. Schnabel was such an artist last night. There was passion, power and a broad line in the first two movements of the sonata, and the endlessly difficult final section was wrought with consumate ressource. But it was in the tremendous slow movement – seraphic in its exaltation and poignant in its searching compassion – that Mr. Schnabel did the most profoundly moving playing of the evening. There are no many pianists abroad who can do justice to this movement. Mr. Schnabel was in the vein last night and his interpretations of the three earlier sonatas were marked with a characteristic regard both for detail and the full sweep of a work. The C sharp minor Sonata (n°14 Op.27 n°2), for years the favorite of any keyboard pounder, assumed a new vitality.’

3 réponses sur « Schnabel – Beethoven Sonates – V/VII – Sonates n°4 Op.7 – n°14 Op.27 n°2 – n°10 Op.14 n°2 – n°29 Op.106 »

HD/Hi-Res (24 bits/88 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZazyzZXUAajW8wS3HrMWzmB4givhG3gUD7

Format CD (16 bits/44 KHz):

https://e.pcloud.link/publink/show?code=kZvLyzZBbPpyi7DgQJL3CgngqE7VF7eQC4k

Great! Thank You and thank You as well for all the information accompanying .-)

Thank you so much, as always, for the stellar transfers and fabulous documentation!