Étiquette : Bande/Tape

Karel Ančerl – Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO)

Berkshire Festival – Tanglewood Shed

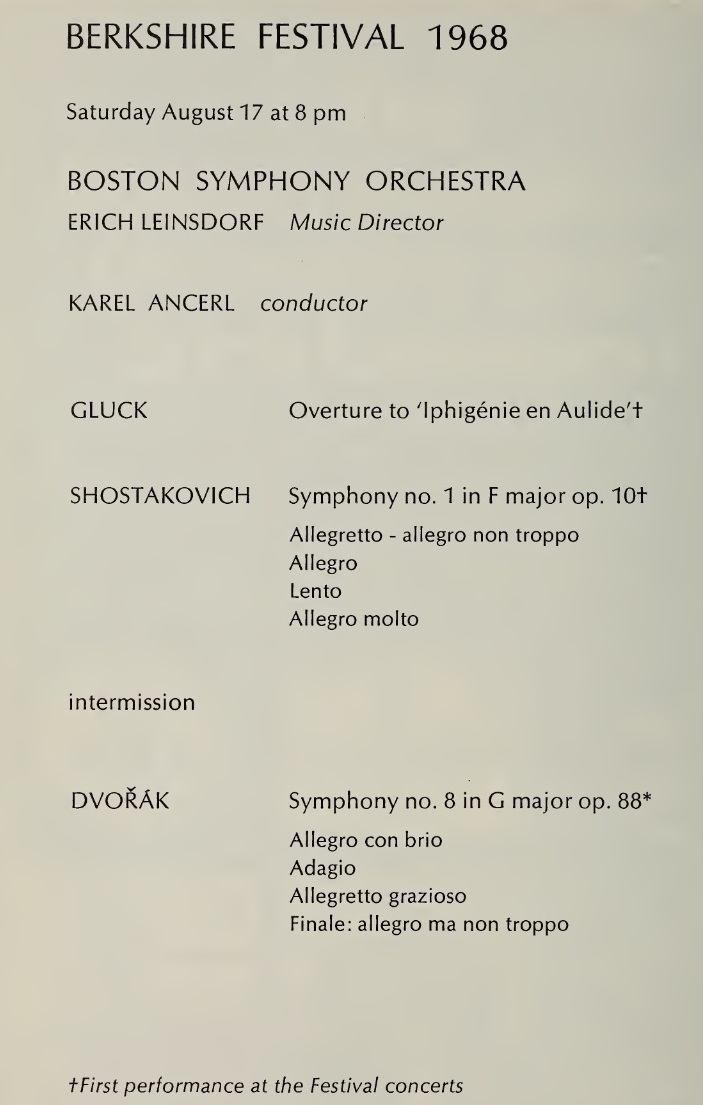

Gluck Iphigénie en Aulide Ouverture – Dvořák Symphonie n°8 Op.88 August 17, 1968

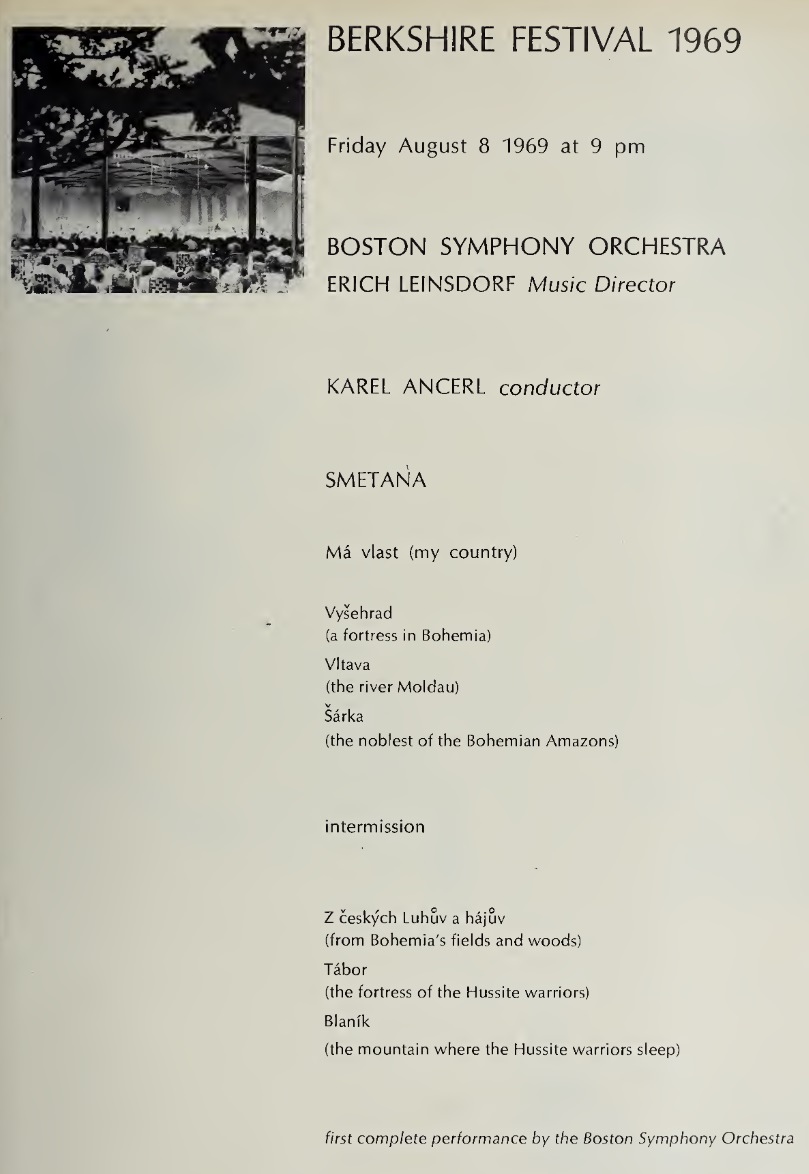

Smetana Ma Vlast (Vysehrad, Vltava, Sarka) August 8, 1969

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

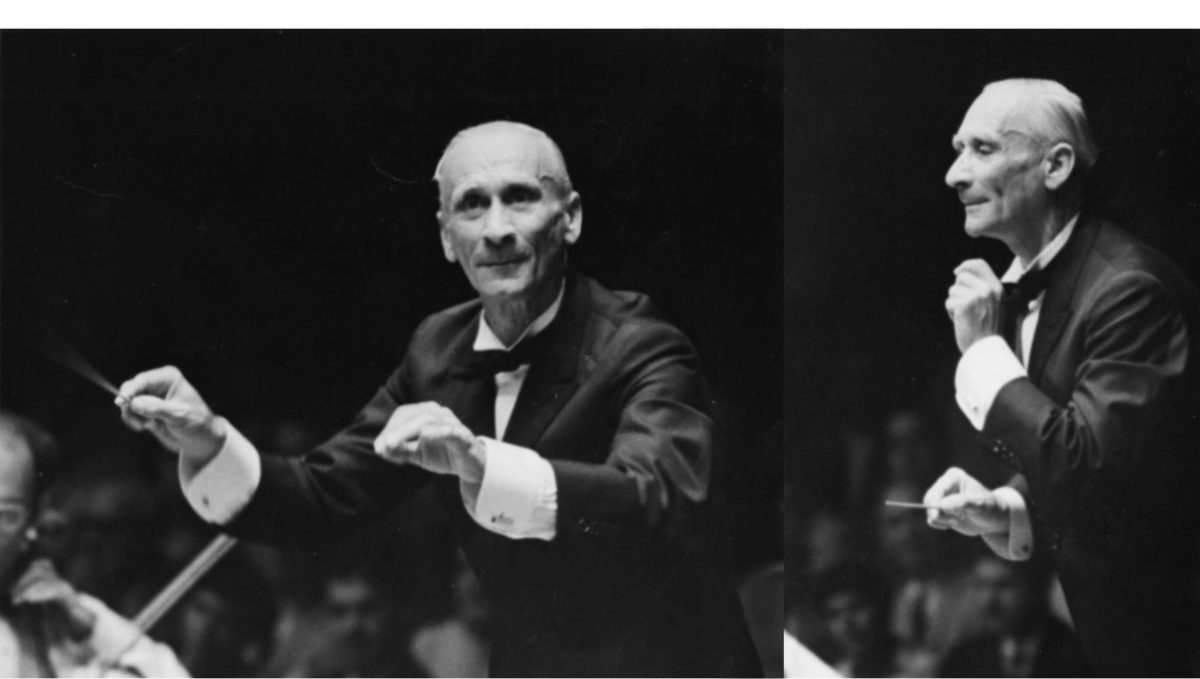

Karel Ančerl n’a dirigé que trois concerts avec le BSO, à chaque fois à Tanglewood au cours du Festival d’été (Berkshire Festival) en 1968, 1969 et 1972.

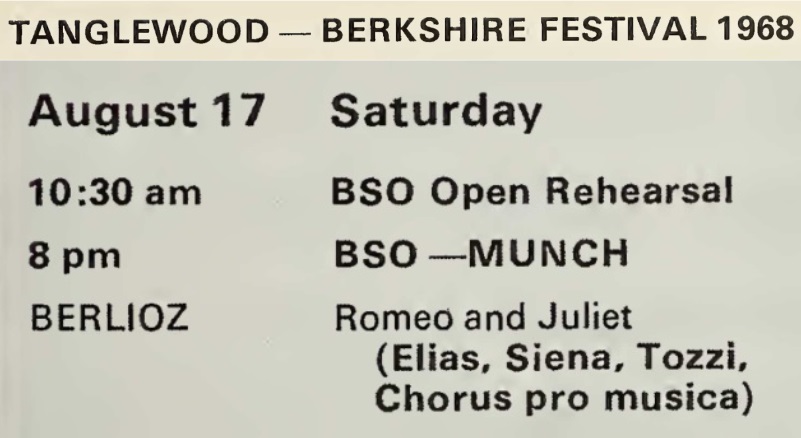

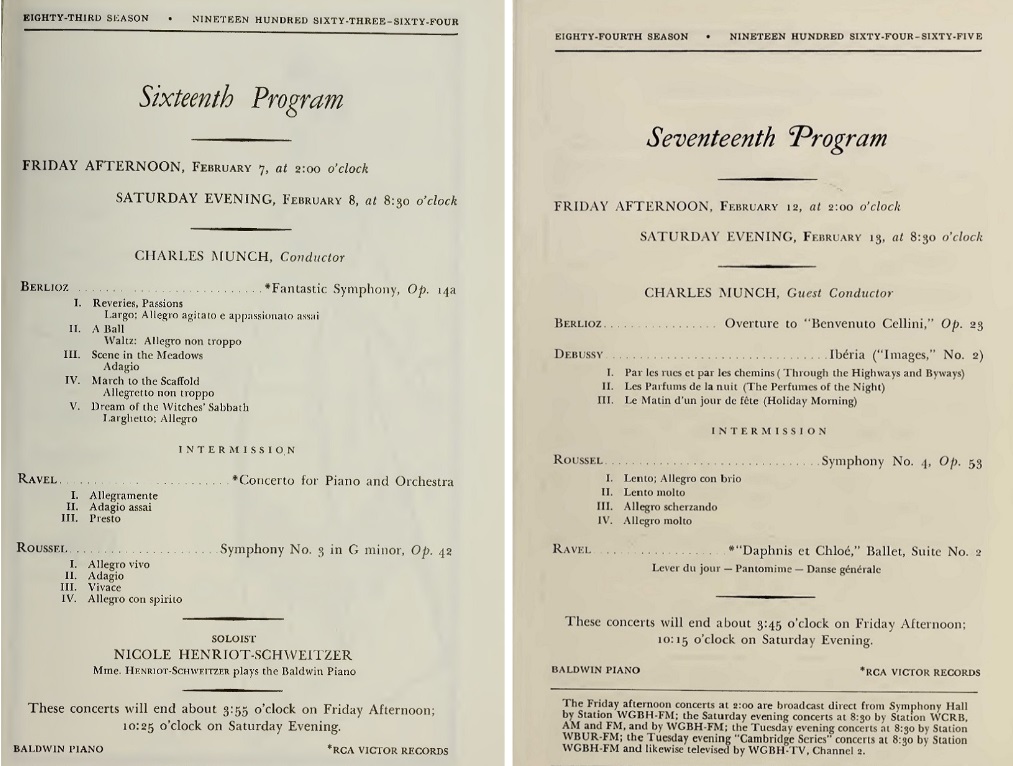

Le concert du 17 août 1968 devait à l’origine être donné par Charles Munch avec au programme l’intégrale de Roméo et Juliette de Berlioz qu’il avait dirigée à Boston la même année les 19 et 20 janvier:

En 1967, Munch a fondé l’Orchestre de Paris sur la base de l’ancienne Société des Concerts du Conservatoire. Entre le 14 novembre 1967, date du concert inaugural du nouvel orchestre et le 23 mars 1968, il a dirigé 4 programmes dont chacun a été joué à cinq reprises. Des séances d’enregistrement avec l’Orchestre de Paris ont eu lieu du 23 au 28 octobre 1967 (Berlioz, Honegger) et les 8 et 12 janvier 1968 (Brahms), mais aussi avec l’Orchestre National de l’ORTF les 10 et 16 février 1968 (Debussy).

Munch, malade, n’a pu assurer la tournée en URSS de l’Orchestre de Paris du 14 au 29 avril 1968, ni les concerts prévus en juillet au Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, et il a aussi annulé ses prestations du mois d’août avec les orchestres de Boston et de Cleveland.

Il n’est revenu au pupitre de son nouvel orchestre qu’en septembre pour des enregistrements d’œuvres de Ravel (21 septembre – 3 octobre 1968) et trois concerts les 9, 10 et 12 octobre, avant de partir pour la fatale tournée d’octobre-novembre au Canada, aux États-Unis et au Mexique. Au cours de cette tournée, il donnera son dernier concert à Boston le 23 octobre.

Pour le concert du 17 août 1968 avec le BSO, Ančerl, qui, aux États-Unis, devait initialement diriger seulement deux concerts avec l’Orchestre de Cleveland au tout nouveau Blossom Music Festival (23 & 24 août, avec notamment les trois œuvres programmées à Boston), a quitté une semaine plus tôt que prévu la Tchécoslovaquie, de sorte qu’il a échappé à l’invasion de son pays le 21 août.

Ančerl a été ré-invité l’année suivante à Tanglewood (Berkshire Festival) pour diriger le 8 août 1969 la Première audition intégrale par le BSO du cycle Ma Vlast de Bedřich Smetana:

Avant ce concert, il a dirigé en juillet de nouveau deux concerts (10 & 12 juillet) avec l’Orchestre de Cleveland au Blossom Music Festival, ainsi que trois concerts (21, 22 & 24 juillet) avec l’Orchestre de Philadelphie (Robin Hood Dell). Ensuite, au mois d’août, il a donné neuf concerts d’été (12 – 29 août) avec le New-York Philharmonic.

De son vivant, Ančerl n’a pas été considéré à sa juste valeur par la presse américaine, surtout la presse new-yorkaise qui le considérait comme un chef « compétent et expérimenté », mais un peu réservé. Cependant, ces extraits de ces deux superbes concerts avec le BSO ne sauraient confirmer de telles opinions. Ils montrent une affinité aussi immédiate que profonde entre lui et le BSO, que le contexte dramatique du concert de 1968 semble renforcer.

Malheureusement, la seconde partie du concert triomphal de 1969 est rendue difficilement audible à cause d’un de ces violents orages d’été déjà fréquents en Nouvelle-Angleterre sur les monts Berkshire.

Il est étonnant qu’Ančerl, qui a ainsi assuré la première audition de Ma Vlast par le BSO, n’ait pas été invité pour redonner cette œuvre à Boston. Mais l’orchestre avait déjà pour projet de la faire diriger et enregistrer en 1971 par Rafael Kubelik dans le cadre de son contrat avec DGG. Et Ančerl, qui, comme annoncé en mars 1968, avait signé un contrat pour devenir le directeur musical de l’Orchestre de Toronto à partir de la saison 1969/70, notamment pour se mettre à distance de démarches en cours à Prague en vue de son remplacement par Kubelik à la tête du Philharmonique Tchèque, a ainsi retrouvé un problème analogue à Boston, mais pour de toutes autres raisons.

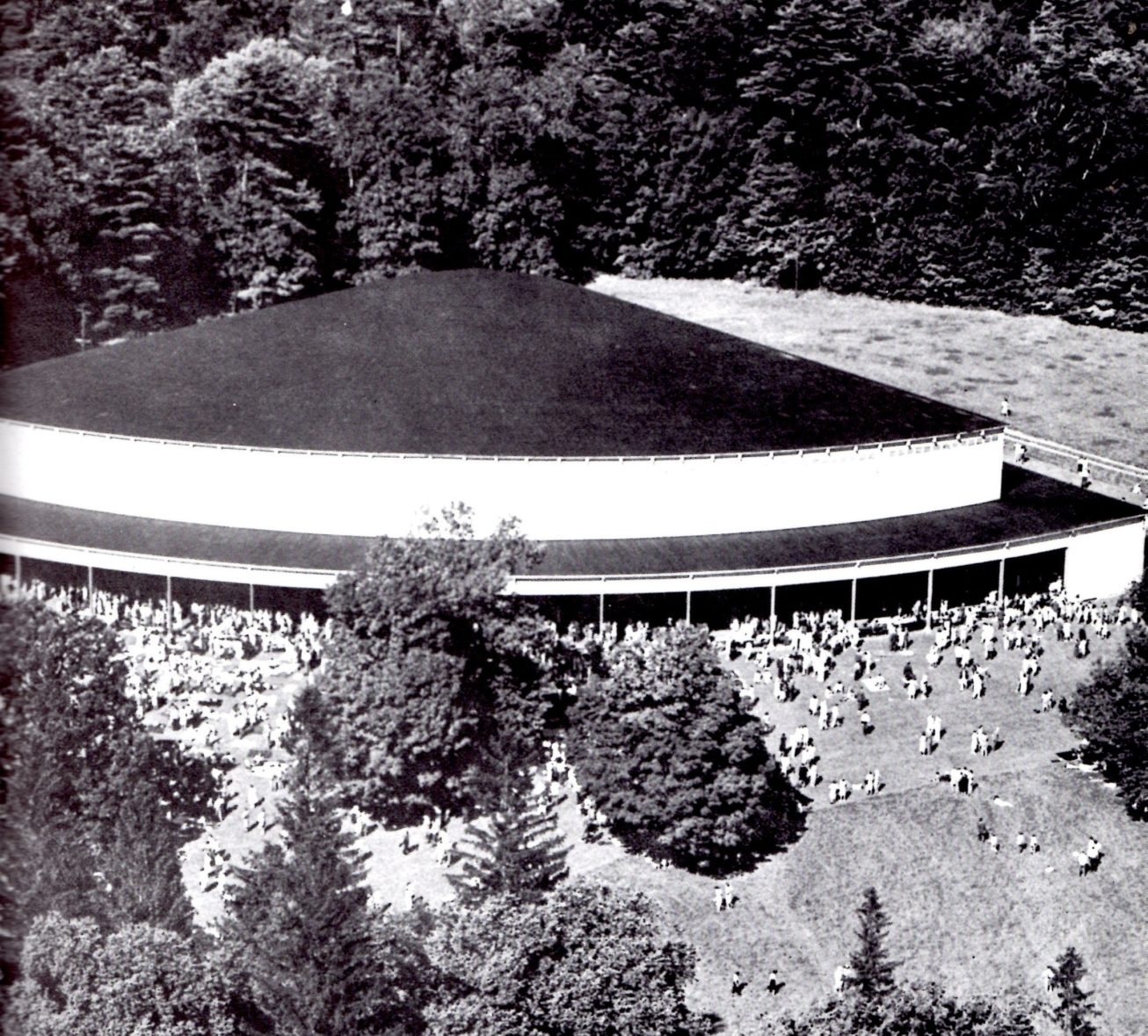

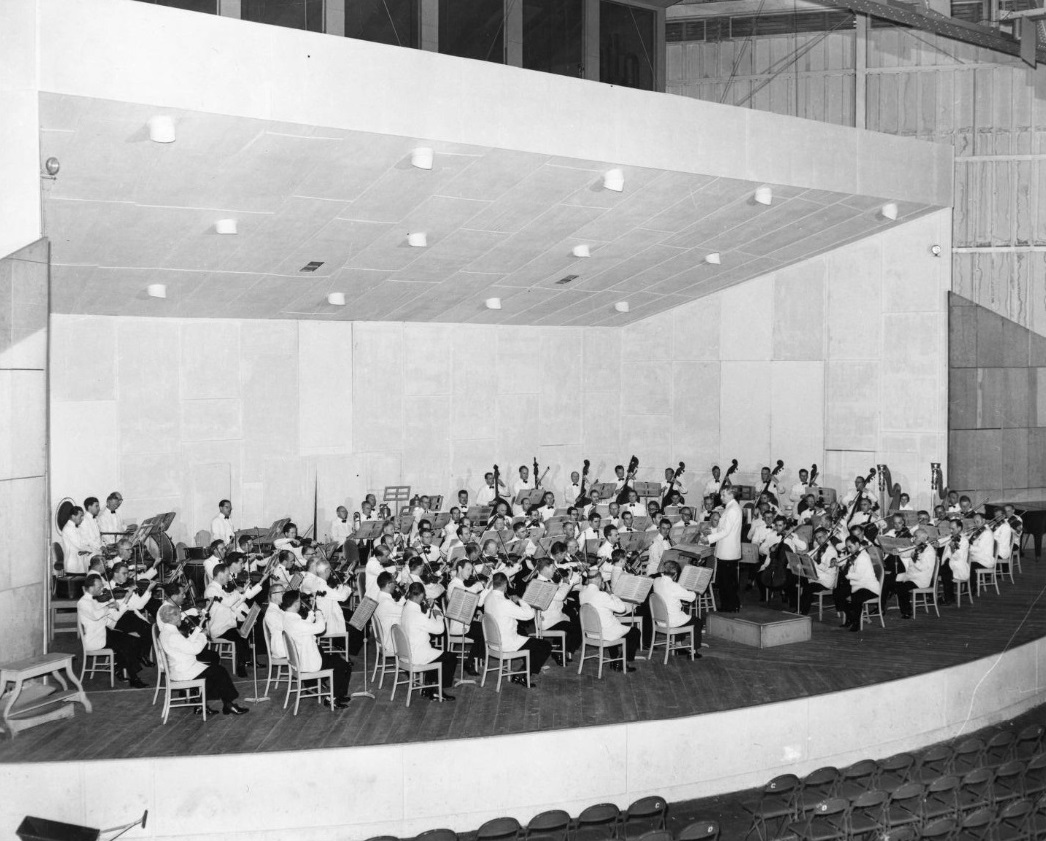

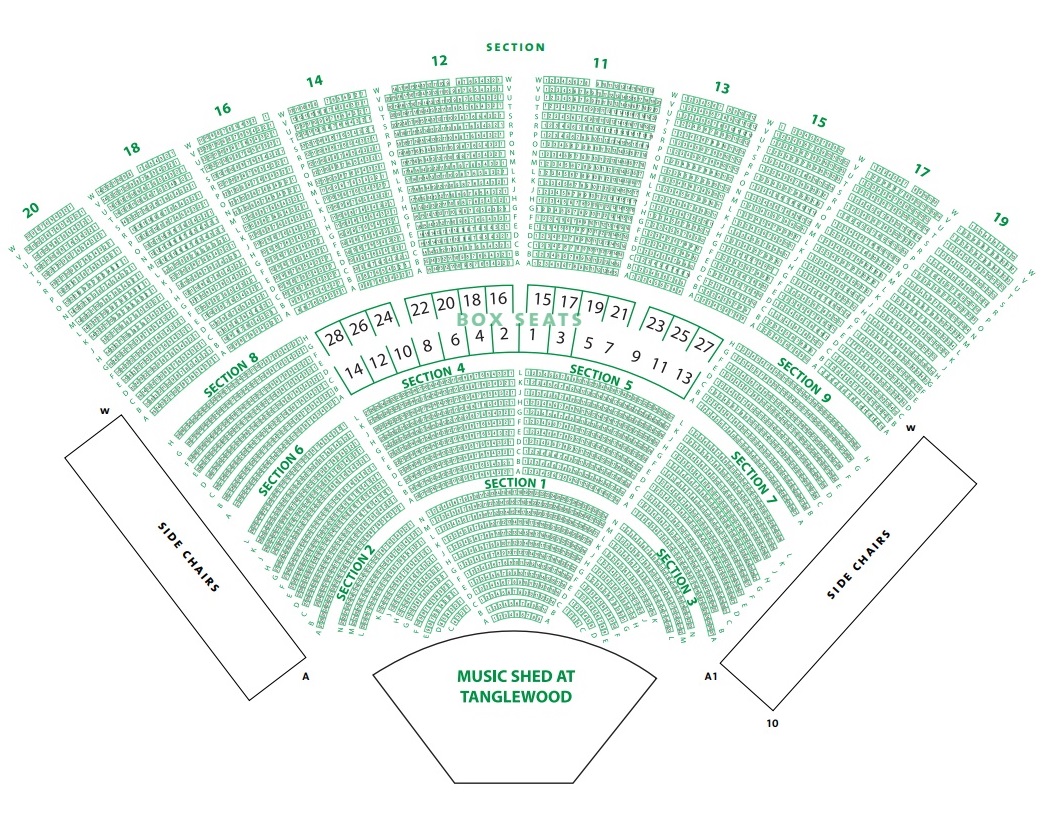

La salle dénommée « Tanglewood Shed » (« hangar ») où sont donnés les concerts symphoniques du Berkshire Festival a été construite en 1938 par Eli Saarinen. Il s’agit d’une structure en acier sur piliers, en forme de triangle ayant un côté curviligne, avec des rangs de sièges disposés en arc de cercle (5100 places), et ouverte sur les côtés et sur l’arrière. Elle donne sur une vaste pelouse qui permet de doubler le nombre de spectateurs. La qualité remarquable de son acoustique, que l’on perçoit nettement dans les enregistrements qui ont à la fois de la largeur et de la profondeur, est due à une structure très innovante pour l’époque composée de panneaux réflecteurs placés au dessus de l’orchestre et d’une partie du public, le « Talbot Canopy », installé en 1959 pour remplacer la classique « conque acoustique » qui existait jusque là.

Tanglewood Shed

Munch BSO 1951 Acoustic Shell / Conque Acoustique

Munch BSO 1959 – « Talbot Canopy »

______________

Karel Ančerl conducted only three concerts with the BSO, each time in Tanglewood during the summer Festival (Berkshire Festival) in 1968, 1969 and 1972.

The concert of August 17, 1968 was scheduled to be conducted by Charles Munch with a complete performance of Berlioz’s Roméo et Juliette which he already conducted that same year in Boston on January 19 and 20.

In 1967, Munch founded the « Orchestre de Paris » on the basis of the old « Société des Concerts du Conservatoire ». Between Entre November 14, 1967, date of the inaugural concert of the new orchestra and March 23, 1968, he conducted four programs, each of which was performed five times. Recording sessions took place with the « ‘Orchestre de Paris » from October 23 to 28, 1967 (Berlioz, Honegger) and on January 8 and 12, 1968 (Brahms), but also with the « Orchestre National de l’ORTF » on February 10 and 16, 1968 (Debussy).

Munch, who fell ill, was not able to conduct neither during the USSR Tour of the « ‘Orchestre de Paris » from April 14 to 29, 1968, nor the scheduled July concerts at the « Festival d’Aix-en-Provence », and he also cancelled his August concerts with the Boston and the Cleveland orchestras.

It was not until September that he came back to his new orchestra for studio recordings of works by Ravel (September 21 – October 3, 1968) and three concerts in October 9, 10 and 12, before leaving for the valedictory October- November Tour in Canada, USA, and Mexico. Durind this Tour, he conducted his last Boston concert on October 23.

For the August 17, 1968 concert with the BSO, Ančerl, who, in the US, was initially scheduled to conduct only two concerts with the Cleveland Orchestra at the newly created Blossom Music Festival (August 23 & 24 with among others the three same works programmed in Boston), left Czechoslovakia one week earlier than scheduled, well before the August 21 invasion of his country.

Ančerl was re-invited the following year () in Tanglewood (Berkshire Festival) to conduct on August 8, 1969 the first complete performance by the BSO of Bedřich Smetana’s Cyle Ma Vlast.

Before this, in July, he conducted again two concerts (July 10 & 12) with the Cleveland Orchestra at the Blossom Music Festival, and also three concerts (July 21, 22 & 24 July) with the Philadelphia Orchestra (Robin Hood Dell). Then, in August, he gave nine summer concerts ( August 12 – 29) with the New-York Philharmonic.

During his lifetime, Ančerl has not been fully recognized by the US critics, especially in New-York where he was rated as a « competent and experienced », but somewhat reserved conductor. However, these excerpts from these two great concerts are likely to challenge such opinions. They show between him and the BSO an affinity both immediate and deep, which the dramatic context of the 1968 concert seems to increase.

Unfortunately, the second half of the 1969 triumphal concert is almost unlistenable due to one of these violent summer thunderstorms that were already quite frequent in New-England over the Berkshires.

It is astonishing that Ančerl, who was in charge of the first performance of Ma Vlast by the BSO, has not been invited to conduct it in Boston. But the orchestra schedule was already to have it performed and recorded in 1971 Rafael Kubelik within the terms of the contract with DGG. And Ančerl, who, as announced in March 1968, signed an agreement to become music director of the Toronto Orchestra from the 1969/70 season, a.o. to free himself from the steps being taken in Prague to replace him by Kubelik as permanent conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, thus met a similar problem in Boston, but for quite different reasons.

The venue named « Tanglewood Shed » where the symphony concerts of the Berkshire Festival take place was built in 1938 by Eli Saarinen. It is a metal structure on pillars, shaped as a triangle with a curved side, with seat rows arranged in arc of circle (5100 seats), and open on its sides and on the back on a large lawn to double the number of spectators. Its remarkable acoustic quality, which may be clearly heard on the recordings which have both width and depth, is due to a then very innovative structure comprised of reflective panels above the orchestra and part of the public, the « Talbot Canopy », installed in 1959 to replace the already existing « Acoustic Shell ».

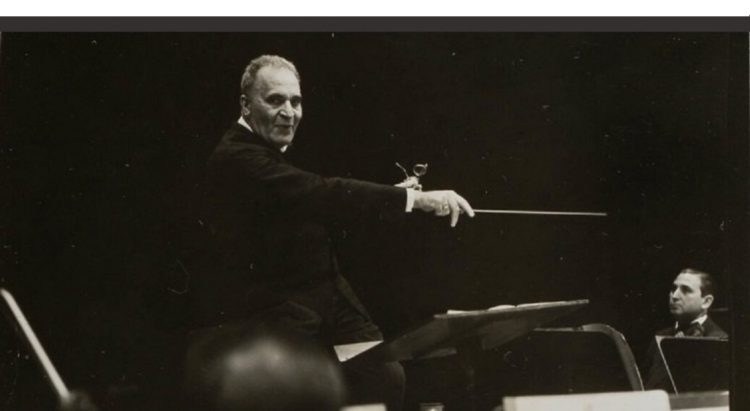

Albert Roussel Charles Munch BSO

Symphonie n°3 Op.42 Boston Symphony Hall – February 7, 1964

Symphonie n°4 Op.53 Boston Symphony Hall – February 12, 1965

Bacchus et Ariane Suite n°2 – Tokyo Hibiya Kokaido May 5, 1960

Source: Bande/Tape 2 pistes 19 cm/s / 2 tracks 7.5 ips

Dès le début de sa carrière de chef d’orchestre, Charles Munch a dirigé des œuvres d’Albert Roussel, à savoir: en 1933 Bacchus et Ariane, en 1934 le Psaume LXXX, et en 1937 la Rhapsodie Flamande, et à chaque fois, à la grande satisfaction du compositeur.

Il est surprenant qu’au cours dès treize années pendant lesquelles il a été le directeur musical du BSO, il n’ait enregistré pour le disque que la Suite n°2 de Bacchus et Ariane. En effet, à Boston, il a dirigé la Symphonie n°3 Op.42 en 1947, 1948, 1951 et 1954 et la Symphonie n°4 Op.53 en 1949 et en 1959, à chaque fois pour une série de concerts comme c’était l’usage à Boston, mais aussi le Concerto pour piano, le Festin de l’Araignée, la Suite en fa, et la Rhapsodie Flamande.

Après sa démission en 1962, il est revenu tous les ans à Boston comme chef invité, en programmant la Symphonie n°3 Op.42 en 1964 puis la n°4 Op.53 en 1965, l’année de ses enregistrements de ces deux symphonies (et de la Suite en fa) avec l’Orchestre Lamoureux, qui sont immédiatement devenus des références discographiques. Ces enregistrements publics qui documentent ses interprétations à Boston de deux œuvres au cœur de son répertoire n’en sont que plus précieux.

Ses derniers concerts avec le BSO ont eu lieu les 18, 19, 20, 23 et 25 janvier 1968 avec l’audition intégrale du Roméo et Juliette de Berlioz.

La Suite n°2 de Bacchus et Ariane était un des chevaux de bataille de Munch, avec pas moins de 70 exécutions avec le BSO entre 1946 et 1965, dont 7 au cours de la tournée de 1960 (« Far East Tour »). Au cours de cette très longue tournée qui s’est étendue du 29 avril au 17 juin, l’orchestre, sous la direction de Charles Munch, d’Aaron Copland et de Richard Burgin (Concert-master de l’orchestre), a donné 34 concerts à Taïwan, au Japon, aux Philippines, en Australie et en Nouvelle Zélande.

Le concert public du 5 mai a eu lieu le lendemain du concert officiel télévisé donné à Tokyo dans la Salle de concert de la NHK (Beethoven Symphonie n°3, Ravel Daphnis et Chloé Suite n°2), le tout premier concert du BSO au Japon (DVD NHK Classical NSDS-9486).

____________

____________

Since the beginning of his career as a conductor, Charles Munch performed works by Albert Roussel, namely: in 1933 « Bacchus et Ariane », in 1934 the Psalm LXXX, and in 1937 the « Rhapsodie Flamande » (Flemish Rapsody), and each time the composer was very happy with his performances.

It is surprising that, during his thirteen year tenure as music director of the BSO, he only recorded commercially the Suite n°2 of « Bacchus et Ariane ». Indeed, in Boston, he conducted the Symphony n°3 Op.42 in 1947, 1948, 1951 and 1954, and the Symphony n°4 Op.53 in 1949 and in 1959, each time for a series of concert, as was usual in Boston, but also the Piano Concerto, the « Festin de l’Araignée » (Spider’s Feast), the Suite in F, and the « Rhapsodie Flamande » (Flemish Rapsody).

After he resigned in 1962, he came back to Boston every year as guest conductor, and he performed the Symphony n°3 Op.42 in 1964 and then n°4 Op.53 in 1965, the very year when he recorded commercialy both Symphonies (as well as the Suite in F) with the Lamoureux Orchestra, which immediately became reference recordings. These public performances which document his interpretations in Boston of these two works at the very heart of his repertoire are all the more treasurable.

His last concerts with the BSO took place January 18, 19, 20, 23 and 25, 1968 with complete performances of Berlioz’s « Roméo et Juliette ».

Suite n°2 of « Bacchus et Ariane » was one of Munch’s favourites, with no less than 70 performances with the BSO between 1946 et 1965, 7 of them during the 1960 Tour (« Far East Tour »). During this very long Tour which took place between April 29 and June 17, the orchestra, conducted by Charles Munch, Aaron Copland and Richard Burgin (the orchestra Concert-master), gave 34 concerts in Taïwan, Japan, Philippine Islands, Australia and New-Zealand.

The May 5 public concert took place the day after the official televised concert given in Tokyo in the NHK Concert Hall (Beethoven Symphony n°3, Ravel « Daphnis et Chloé » Suite n°2), the very first BSO concert in Japan (DVD NHK Classical NSDS-9486).

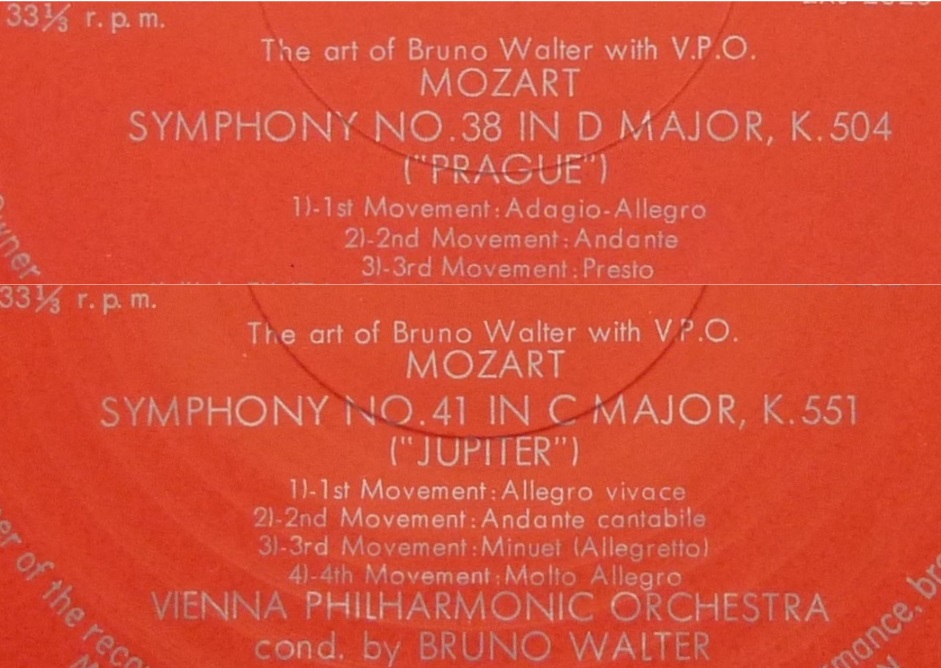

Mozart

Symphonie n°38 K.504 WPO Musikvereinsaal 18 Dezember 1936

Symphonie n°41 K.551 WPO Musikvereinsaal 11 Januar (Jänner) 1938

Source: 33t. Angel Japan « The Art of Bruno Walter with WPO »

Bruno Walter & Arnold Rosé

________

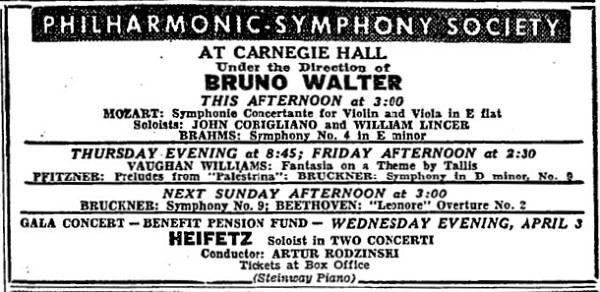

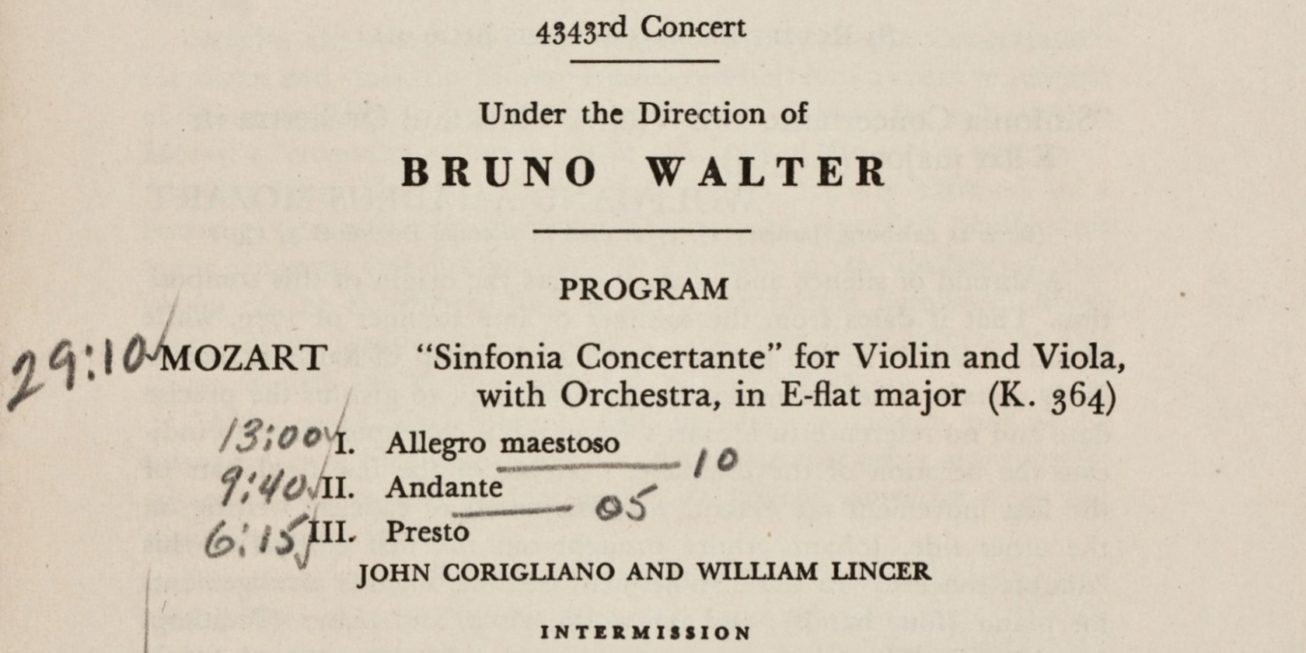

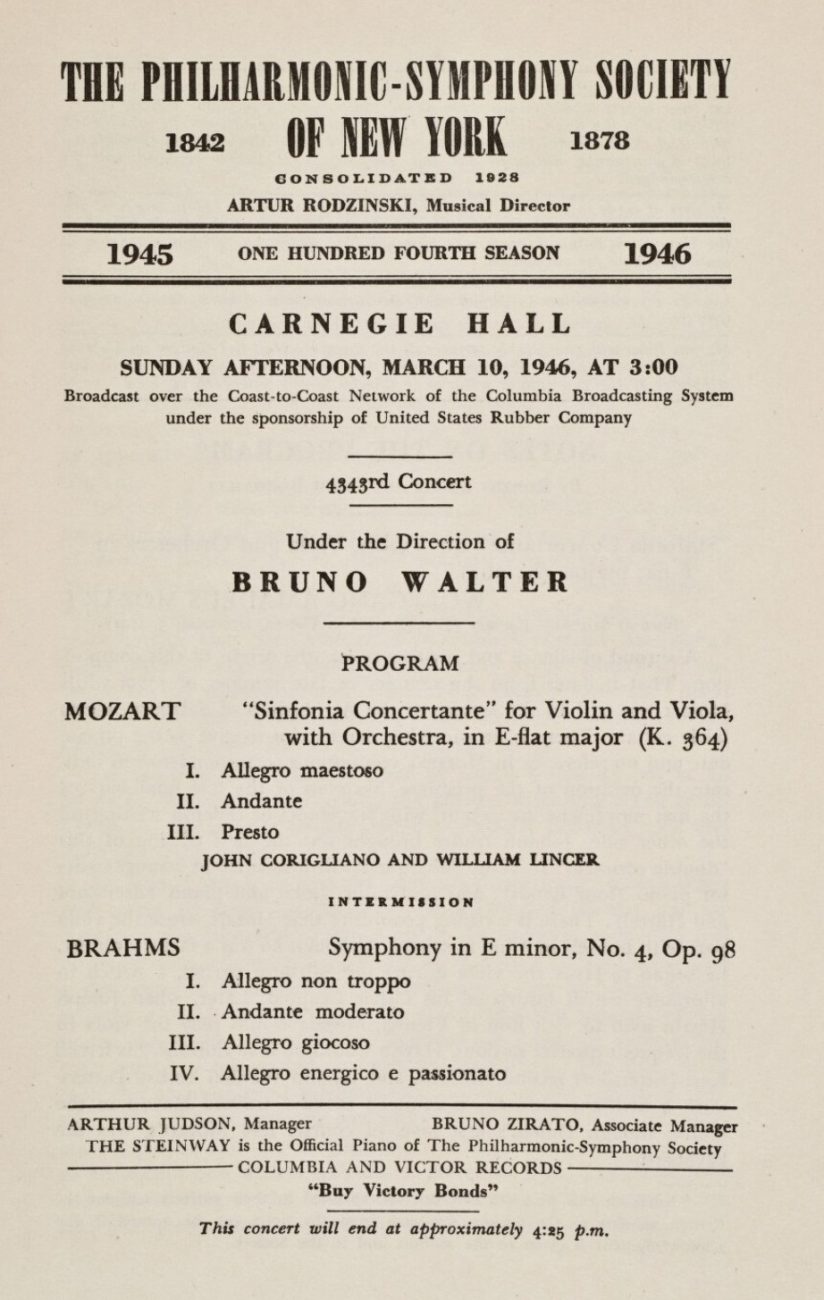

Sinfonia Concertante K.364 NYPO John Corigliano & William Lincer Carnegie Hall 10 March 1946 Source: Bande/Tape (origine: disques/transcription discs)

William Lincer & John Corigliano

________

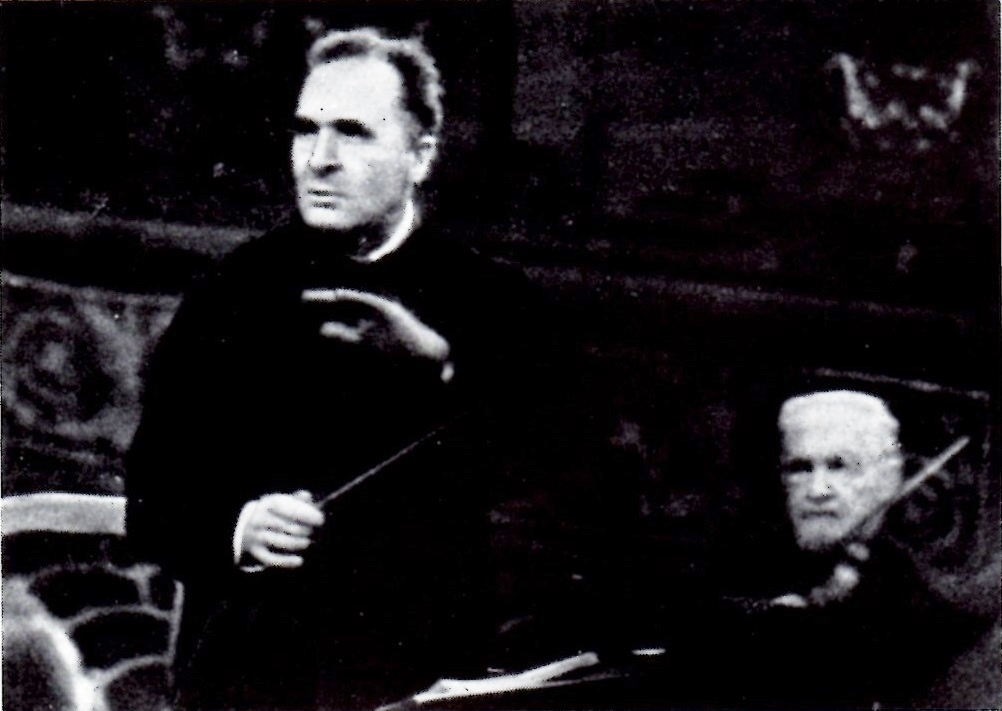

Ces trois enregistrements de Bruno Walter représentent la fin de son activité à Vienne avant la guerre, la Symphonie n°41 accompagnant les 15 et 16 janvier la Neuvième de Mahler au cours de sa dernière série de concerts avant l’Anschluss, ainsi que son unique enregistrement accessible de la Symphonie Concertante pour violon et alto K.364 lors du concert du 10 mars 1946. Il avait déjà dirigé cette œuvre à New York les 5 et 6 mars 1925 avec en solistes Samuel Duskin et Lionel Tertis, et il l’a redonnée les 12 et 13 février 1953 avec Corigliano et Lincer, mais sans retransmission radiophonique à cette occasion. Un enregistrement de concert à Chicago (concert télévisé du 25 janvier 1956 avec John Weicher et Milton Preeves) a été recensé dans une archive privée, mais n’a pas été publié. Le concert du dimanche 10 mars 1946 est particulier en ce sens que son programme (Mozart K364, Brahms Symphonie n°4) est complètement différent de celui des concerts des 7 et 8 mars consacrés à la Passion selon St-Matthieu de Bach, alors qu’en général, le programme radiodiffusé le dimanche reprend en partie le programme de la semaine.

Concernant l’interprétation de la Sinfonia Concertante de Mozart, le critique Noel Straus écrivait: ‘John Corigliano, le concertmaster de l’orchestre, et William Lincer, son premier alto, ont été les solistes de l’opus de Mozart, qui, comme le Brahms, a bénéficié d’une lecture des plus élaborées et des plus élevées. Aucune interprétation ne peut être d’un esprit aussi complètement mozartien que celle qui a été donnée de la Sinfonia Concertante, une oeuvre unique en son genre qui n’a rien perdu de sa fraîcheur juvénile et de son grand attrait au cours des 167 années qui se sont écoulées depuis sa composition. Sous une direction moins, cette composition exquisément façonnée peut facilement dégénérer de la part des deux solistes en une exhibition de virtuosité. Même si une bravoure experte était apportée aux mesures en solo, la musique elle-même et la révélation de sa pleine signification étaient le souci principal de Mr. Walter, et il a montré que c’était possible sans exagérer la composante soliste, avec pour résultat qu’un parfait sens de l’équilibre, rarement obtenu dans cette oeuvre à l’orchestration légère, a été rendu possible. Avec cette manière de faire, la composition a gagné en intimité, et rien n’a été oublié pour projeter le caractère sensible et poétique de son contenu. L’art et la compétence technique de Mr. Corigliano et de Mr. Lincer étaient si complètement en harmonie, leurs sonorités si subtilement intégrées et équilibrées, que leurs jeux formaient remarquablement un tout, et s’inscrivaient en même temps dans le cadre dynamique qui convenait exactement à la fusion avec un accompagnement orchestral finement conçu. Il est difficile d’imaginer un rendu plus éloquent et plus convaincant, ou plus admirable par sa pureté tonale, la beauté de sa texture, par ses couleurs et par son expressivité.’

These three Bruno Walter recordings illustrate the end of his pre-war tenure in Vienna, the Symphony n°41 being played on the 15 and 16 January together with the Mahler Ninth during his last series of concerts there before the Anschluss, as well as his only available recording of the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola K.364 during the concert of March 10, 1946. He already conducted this work in New York on 5 and 6 March 1925 with Samuel Duskin and Lionel Tertis as soloists, and he performed it again on 12 and 13 February 1953 with Corigliano et Lincer, but without broadcast this time. A concert recording in Chicago (TV concert on 25 January 1956 with John Weicher and Milton Preeves) has been listed in a private archive, but hasn’t been published. The concert of Sunday 10 March 1946 is special in the sense that its program (Mozart K.364, Brahms Symphony n°4) is entirely different from the preceding ones on 7 and 8 March dedicated to Bach’s Passion according to St-Matthew, whereas usually, the program of the Sunday broadcast is partly comprised of works played during the week.

Concerning the performance of the Sinfonia Concertante by Mozart, music critic Noel Straus wrote: ‘John Corigliano, the orchestra’s concertmaster and William Lincer, its first viola, were the soloists in the Mozart opus, which, like the Brahms work, gloried in a reading of a most searching and exalted nature. No performance could be more completely Mozartean in spirit than that given of the Sinfonia Concertante, an unrivaled work of its genre that has lost nothing of its youthful freshness and deep appeal with the passage of the 167 years since its creation. Under less fully comprehending direction, the exquisitely wrought composition easily can become first and foremost an exhibition of virtuosity on the part of the two soloists. But for all the expertness of bravoura brought to the solo measures, the music itself and the revelation of its meaning to the full was the primary consideration with Mr. Walter and this he found possible without overstressing the solo element with the result that a perfect sense of balance, rarely achieved in this lightly orchestrated score, became possible. The composition gained in intimacy through this type of treatment, and nothing was left undone to project the sensitive, poetic character of its content. The artistry and skill of Mr. Corigliano and Mr. Lincer was so perfectly matched, their tone so subtly integrated and equalized, that their playing proved remarkably unified, and at the same time was held in just the right dynamic frame to blend absolutely with the finely considered orchestral support. It is difficult to conceive of a presentation of this work more eloquent and persuasive, or more admirable in tonal purity, beauty of texture, coloring and expressiveness.’

Brahms: Tragische Ouverture Op.81 NBC SO Manhattan Center – January 15, 1951

Brahms: Symphonie n°1 Op.68 NBC SO – Carnegie Hall – December 6, 1952

______

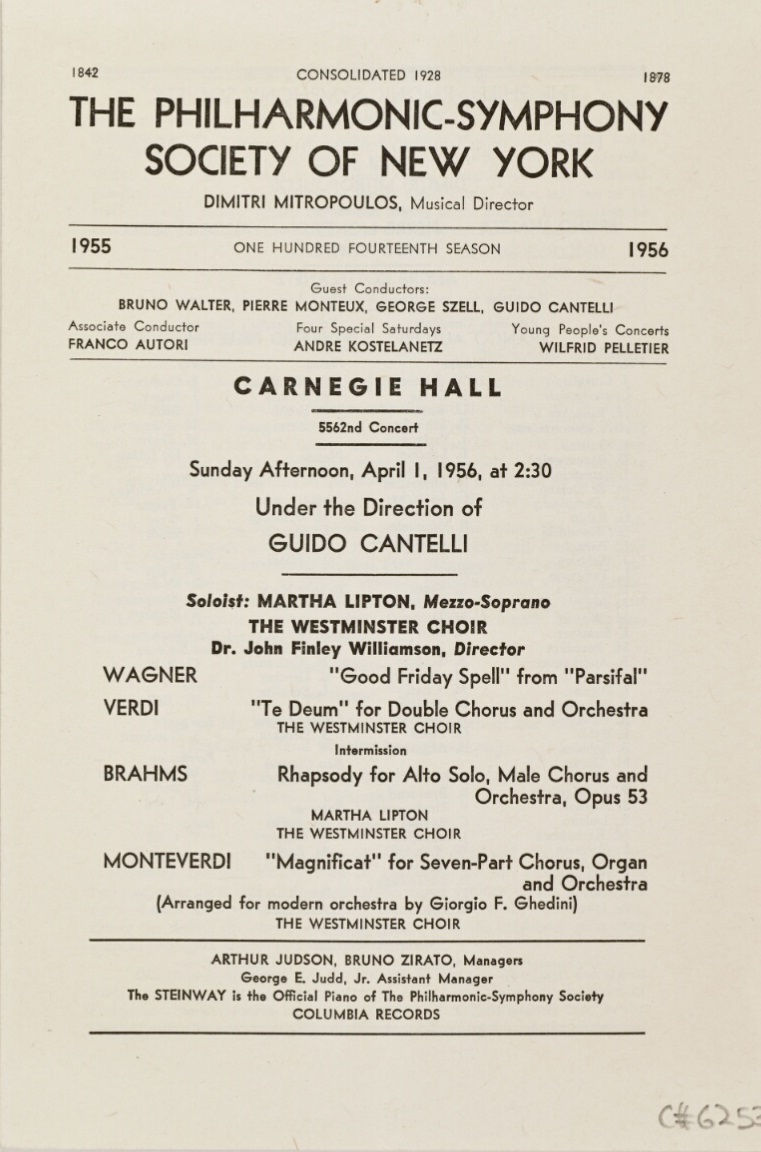

NYPO – Westminster Choir – Carnegie Hall – April 1, 1956

Verdi: Te Deum

Brahms: Alt-Rhapsodie Op.53 NYPO – Martha Lipton

Source: Bande/Tape 19 cm/s / 7.5 ips

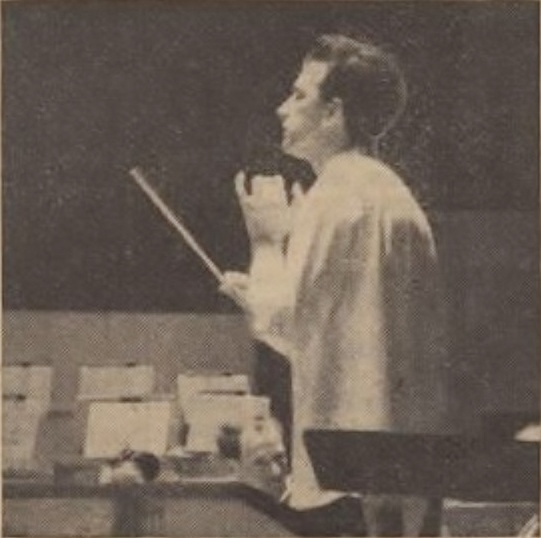

Guido Cantelli a peu donné en concert l’Ouverture Tragique de Brahms Op.81, mais par contre sa Première Symphonie Op.68 est l’œuvre qu’il a le plus dirigé. Fin 1950, la NBC a transformé en studio de TV le studio 8-H où avaient lieu la plupart des concerts du NBC SO, et a décidé de les transférer au Manhattan Center, salle à l’acoustique très réverbérée, ce que Toscanini a refusé, seul Carnegie Hall étant pour lui acceptable, et donc seuls d’autres chefs d’orchestre, dont Cantelli, y ont donné temporairement des concerts avec cet orchestre, et la NBC n’a finalement pu que se plier à sa demande.

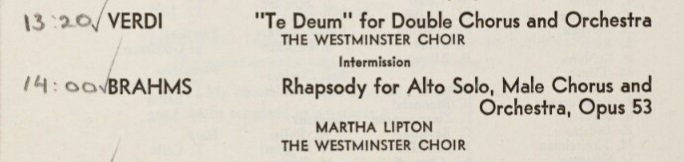

Le Te Deum de Verdi et la Rhapsodie pour contralto, chœurs d’homme et orchestre Op.53 de Brahms ont été mis au programme des concerts des 29, 30, 31 mars, et 1 avril 1956 du New York Philharmonic et c’est la seule fois qu’il les a dirigées.

Guido Cantelli has seldom performed Brahms’ Tragic Overture Op.81, whereas his first Symphony Op.68 was the work he most conducted. At the end of 1950, the NBC transformed Studio 8-H where most of the NBC SO concerts were given, into a TV studio, and decided to tranfer them to Manhattan Center, a venue with much reverberation, which Toscanini refused, only Carnegie Hall being acceptable to him, and thus only other conductors, among them Cantelli, temporarily gave concerts there with this orchestra and eventually the NBC had to comply with his demand.

Verdi’s Te Deum and Brahms’ Rhapsody for contralto, male chorus and orchestra Op.53 were performed at the New York Philharmonic concerts of March 29, 30, 31 and April 1, 1956 and it it the only time he performed them.

NBC SO Carnegie Hall – 15 December 1951 (Bande/Tape)

_________

Philharmonia Orchestra – 8, 9, 12, 16 &18 August 1955 (GHLP 1004-Mono)

La Troisième Symphonie est réputée comme étant la Symphonie de Brahms la plus difficile à interpréter. Si des chefs comme Walter ou Furtwängler ont signé des versions considérées comme des références, elle a posé beaucoup de problèmes même à de grands brahmsiens, à commencer par Toscanini qui, dans ses témoignages enregistrés, ne l’a vraiment réussie qu’avec le Philharmonia Orchestra, en concert à Londres au Royal Festival Hall en 1952.

C’était par contre une des grandes interprétations de Guido Cantelli qui en a laissé trois témoignages enregistrés (NBC SO, Boston SO, Philharmonia Orchestra).

L’enregistrement réalisé pour HMV/EMI à Kingsway Hall en 1955 a été capté à la fois en monophonie et en stéréophonie expérimentale. A cet effet , il y avait deux équipes de prises de son. L’enregistrement stéréophonique n’a été publié qu’en 1978, et depuis, c’est cette seule version qui est rééditée. Toutefois, en comparant ces deux captations, on constate qu’avec l’étalement en largeur de l’orchestre procuré par la stéréo, la réverbération de Kingsway Hall tend à diluer les timbres et à lisser les phrasés, alors que la prise de son mono, bénéficiant d’un judicieux placement microphonique qui permet à l’acoustique ample de la salle de porter pleinement le son de l’orchestre, est bien mieux définie: l’interprétation sonne de manière nettement plus vivante, et les timbres et les détails du phrasé sont mieux restitués. Avec la version mono, on est aussi musicalement plus proche de la version enregistrée en concert avec le NBC SO.

Le tableau des minutages ci-dessous montre qu’en studio avec le Philharmonia, et comme c’était en général le cas avec Cantelli, les tempi sont plus larges. Il montre aussi qu’en concert, Cantelli faisait la reprise (environ 3′) dans le premier mouvement, mais que cette reprise est malheureusement omise dans l’enregistrement commercial avec le Philharmonia.

Minutages/Timings:

NBC SO 15 Dec. 1951 (12’23; 7’57; 5’35; 8’06)

Boston SO 25 Dec. 1954 (12’28; 7’58; 5’45; 8’02)

NYPO 20 Jan. 1955 (12’40; 7’45; 5’40; 8’10)

Philharmonia Orch Aug. 1955 (9’57; 8’43; 6’18; 8’25)

[Philharmonia Orch Toscanini 1 Oct 1952 (12’27; 8’31; 6’17; 8’34)]

Cantelli Philharmonia Edinburgh

Among the Brahms Symphonies, the Third Symphony is considered as being the most difficult to perform. If conductors like Walter or Furtwängler have made recordings considered as references, it proved problematic even for great Brahms conductors, and for Toscanini to start with, who in his recorded testimonies was only successful with his 1952 London concert in Royal Festival Hall with the Philharmonia Orchestra.

On the other hand, it was one of the great performances of Guido Cantelli who left three recordings (NBC SO, Boston SO, Philharmonia Orchestra).

The 1955 recording for HMV/EMI in Kingsway Hall was made both in mono and in experimental stereo. For this purpose, there where two recording teams. The stereophonic version was published only in 1978, and since then, is the only one to be re-issued. However a comparison between both reveals that, because of the Kingsway Hall reverberation, the spreading in width of the orchestra brought by stereophony goes with a lower definition of the timbres and a smoothing of the phrasings, whereas the mono version, because of a well chosen microphone placement that allows the warm hall acoustics to bring a full-blooded orchestral sound, has much more definition: the performance sounds much more alive, and the timbres and the details of phrasing are better reproduced. With the mono version, we are also musically closer to the concert performance recorded with the NBC SO.

The timings (see above) show that in studio with the Philharmonia, and as was generally the case with Cantelli, the tempi are broader. They also show that, in live performances, Cantelli made the first movement repeat (about 3′), but that this repeat was omitted in the commercial recording with the Philharmonia.