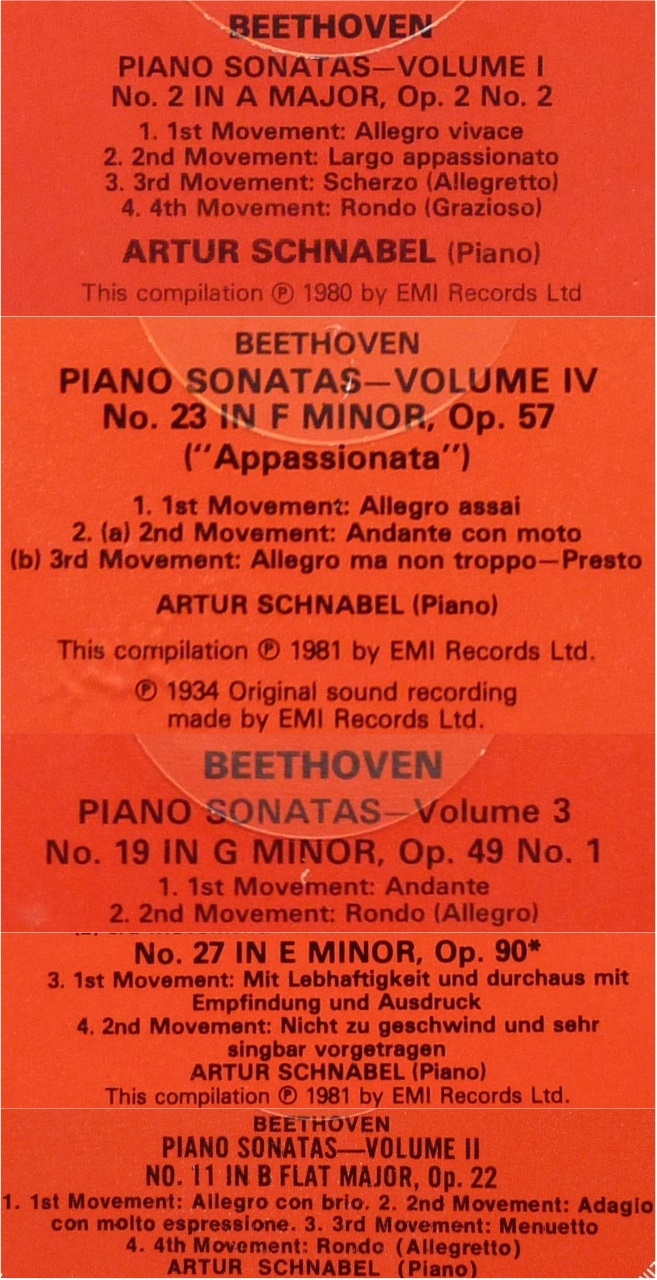

Étiquette : Beethoven

Sonate n°9 Op.14 n°1: 25 Mars 1932

Sonate n°7 Op.10 n°3: 12 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°25 Op.79: 15 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°24 Op.78: 21 Mars 1932

Sonate n°32 Op.111: 21 Janvier, 21 & 22 Mars, 7 Mai 1932

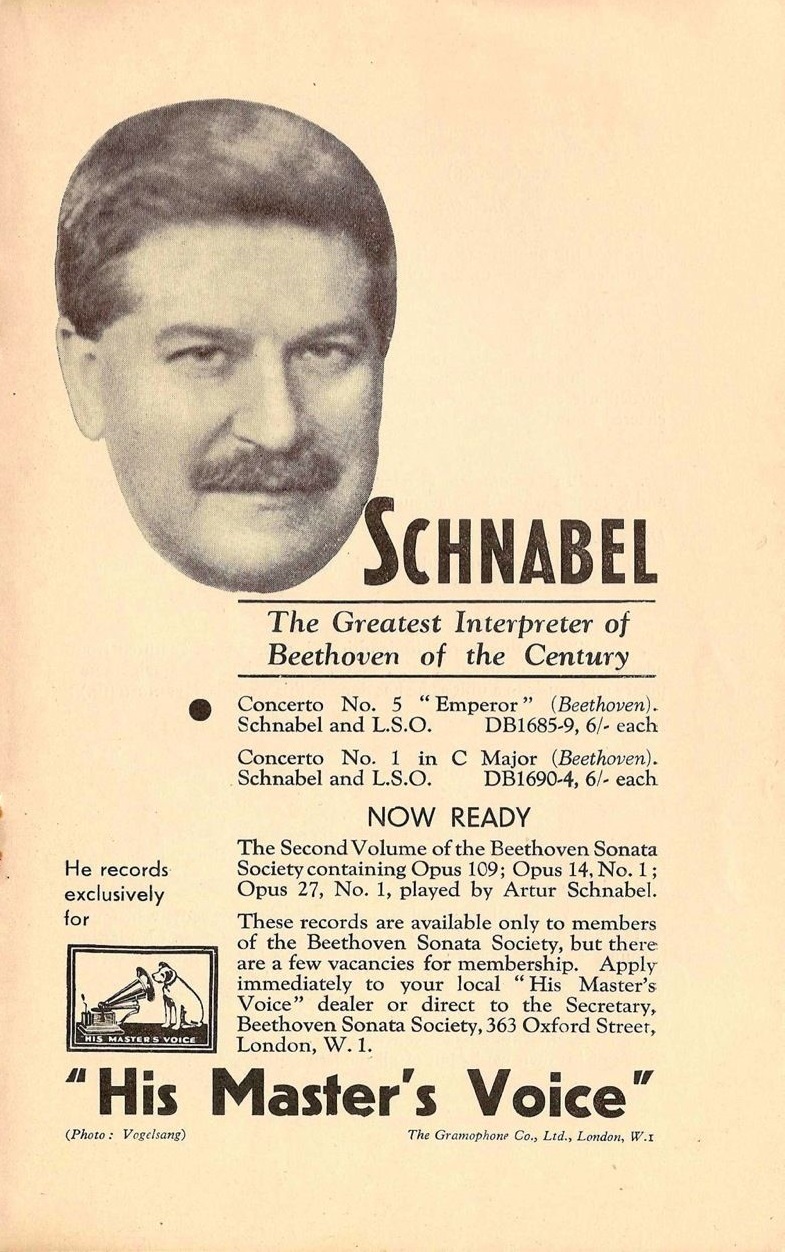

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le septième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comprenait les cinq sonates ci-dessus, les deux premières étant, comme pour les autres récitals, jouées avant l’entracte.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le septième récital, donné le 26 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, a eu lieu au moment où, autre événement de la saison new-yorkaise, Arturo Toscanini poursuivait avec Rudolf Serkin la série de ses concerts d’adieu en tant que chef titulaire du New York Philharmonic. L’interprétation par Schnabel de la sonate n°24 Op.78, dédiée à Therese von Brunswick, a atteint un niveau tel qu’elle a presque ‘ volé la vedette’ à l’Opus 111! (voir la critique ci-dessous). Une idée de génie de la part de Schnabel que d’associer ces deux œuvres pour terminer son intégrale, ce que l’on peut apprécier d’autant plus qu’elles ont été superbement enregistrées ensemble en 1932, et que l’interprétation de l’Arietta conclusive de l’Opus 111 y est vraiment extraordinaire.

Pour le critique: ‘les deux premières sonates de la liste, celle en mi majeur Op.14 n°1 (n°9) et celle en ré majeur Op.10 n°3 (n°7), toutes deux de 1797, quand le compositeur n’avait pas encore atteint la trentaine, représentaient la phase antérieure de son développement. Les sonates en sol majeur Op.79 (n°25) et en fa dièse majeur Op.78 (n°24) servaient à illustrer la maîtrise qui était celle de Beethoven en 1809, alors que l’Opus 111 (n°32) a été réservée pour conclure le programme et toute la série, non seulement parce qu’il s’agissait de la dernière œuvre de Beethoven sous cette forme pour le piano, mais aussi parce qu’elle reste, à bien des égards, la plus grande de toutes les sonates. Cet ultime récital a une fois de plus mis en avant, sans nul doute, l’étonnante musicalité de Mr. Schnabel, qui est tellement évidente à tout instant dans ses interprétations que même le plus néophyte des auditeurs doit en percevoir quelque chose, alors qu’elle ne cesse de stupéfier le public des connaisseurs…… Avec toute l’appréciation qui était due à ce que Mr. Schnabel a accompli hier soir dans l’opus 111, c’est dans le superbe déroulement de la relativement négligée sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) que résidait sa prestation sa plus étonnante et la plus significative. Ici, Mr. Schnabel a revêtu le manteau impérial à la fois de pianiste et d’interprète. Peu de ceux qui ont entendu l’interprétation de la sonate en fa dièse majeur (n°24 Op.78) risqueront de l’oublier, eu égard à son effet d’ensemble, ou bien par rapport à ses détails saillants. La sonate n’est pas entendue souvent, sans doute pour la raison que peu de pianistes la trouvent soit gratifiante, soit facile à unifier pour faire ressortir une relation positive entre ses deux mouvements. La perspicacité de Mr. Schnabel et sa compréhension de ses réelles possibilités ont donné une lecture qui a du re-créer l’œuvre pour chaque musicien dans la salle. Dans l’Allegro qui ouvrait l’œuvre et qui pour une fois n’était pas pris trop rapidement, il y avait des passages d’un charme sonore exceptionnel. Il en était de même des mesures de transition entre les deux sujets principaux pour lesquels les mélodies respectives à la main droite et à la main gauche étaient exquisement modelées sur un fond scintillant de doubles croches dans les accords brisés supérieurs qui était un ravissement pour l’oreille. Mais c’est dans le final que Mr. Schnabel a atteint son zénith à cette occasion. Il serait impossible d’exagérer la magie de ce mouvement, dans lequel la plupart des pianistes pataugent désespérément dans un marais de notes survolées sans signification aucune. Mr. Schnabel, avec sa relecture de cette division de l’œuvre, a enfin projeté une lumière réelle sur sa signification. Et quelle joie cela a été de l’entendre interprétée de sorte que la figuration élaborée qui relie les mouvements entre eux a pris forme et proportion sous les doigts experts du pianiste, d’où elle émergeait comme un moment brillant de bravoure de la plus haute espèce. La place manque pour discuter de la restitution de l’Op.111 (n°32), qui était carrément dramatique dans le premier mouvement et remarquablement originale à certains moments du dernier. Dans l’Arietta, le thème a été énoncé avec le son chantant, la tendresse et la simplicité qu’il exige, mais reçoit rarement. Mais particulièrement admirable était l’atmosphère mystérieuse de la quatrième variation et la délicatesse des figures murmurées de la cinquième variation. C’est avec ce caractère suprême que le pianiste a terminé son magnifique hommage au génie de Beethoven.’

The seventh program for the complete 32 Sonates of Beethoven by Artur Schnabel was comprised of the five above cited sonatas, the first two being, as for the other recitals, played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The seventh recital, given on 26 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, took place when, yet another event of the New York season, Arturo Toscanini pursued with Rudolf Serkin the series of his farewell concerts as music director of the New York Philharmonic. Schnabel’s performance of the sonata n°24 Op.78, dedicated to Therese von Brunswick, was of such a level that it almost ‘stole the show’ to Opus 111! (see below). Indeed, it was a stroke of genius by Schnabel to couple these two works to end his ‘marathon’, which we can appreciate all the more since they have been masterfuly recorded together in 1932, and since the recorded interpretation of the Arietta ending Opus 111 is really extraordinary.

For the critic:’ the first two sonatas on the list, that in E major, Op.14 n°1 (n°9), and that in D major, Op.10 n°3 (n°7), both stemming from 1797, when the composer was still in his twenties, represented the earlier phase of development. The sonatas in G major Op.79 (n°25) and in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) served to illustrate the mastery that was Beethoven’s in 1809, when these were written, while the Op.111 (n°32) was reserved to end the program and the series, not merely because it was Beethoven’s last work in the form for the piano, but because it remains in many respects the greatest of all sonatas. Ths culminating recital of the seven, once again published in no uncertain manner Mr. Schnabel’s astounding musicianship, which is so evident at every moment in his performances that the veriest tyro among his listeners must sense something of it, while it never ceases to amaze the connoisseurs in the audience…. With all due appreciation of what Mr. Schnabel accomplished in the Op.111 last night, his most startling and significant playing was heard in his superb unfolding of the rather neglected sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24). Here, Mr. Schnabel wore the imperial mantle both as pianist and as interpreter. Few who heard the interpretation of the sonata in F sharp major Op.78 (n°24) are likely to forget it, either in respect to its effect as a whole, or in regard to its salient details. The sonata is not often heard, for the reason, undoubtly, that few pianists find it either grateful, or easy to unify by bringing out a positive relation between its two movements. Mr. Schnabel’s insight and his understanding of its real possibilities, resulted in a reading which must have re-created the work for every musician in the house. There were passages in the opening Allegro (which, for once, was not taken too rapidly, as it usually is) of exceptional tonal charm. Such were the transitional measures between the two main subjects, where the respective melodies in the right and left hand were exquisitely molded against a glittering ripple of sixteenths in the upper broken chords that was fairly ravishing to the ear. But it was in the Finale that Mr. Schnabel reached his zenith on this occasion. It would be impossible to overstate his wizardy in this movement, where most pianists flounder hopelessly in a morass of flying notes meaning nothing. Mr. Schnabel, in his re-editing of this division of the work, has at last thrown some real light on its meaning. And what a joy it was to have it performed so that the elaborate figuration that binds the movements together took on shape and proportion under the pianist’s knowing fingers, whence it emerged as a coruscating bit of bravura of the highest type. There is no space to go into a discussion of Mr. Schnabel’s rendition of the Opus 111, which was emphatically dramatic in the first movement and strikingly original in certain phases of the last. In the Arietta, the theme was stated with the singing tone, the tenderness and simplicity it demands and seldom receives. But especially admirable were the mysterious atmosphere created in the fourth variation and the ineffable delicacy of the purling figures of the fifth variant. By art of this superlative nature the pianist completed his splendid tribute to Beethoven’s genius.’

____________

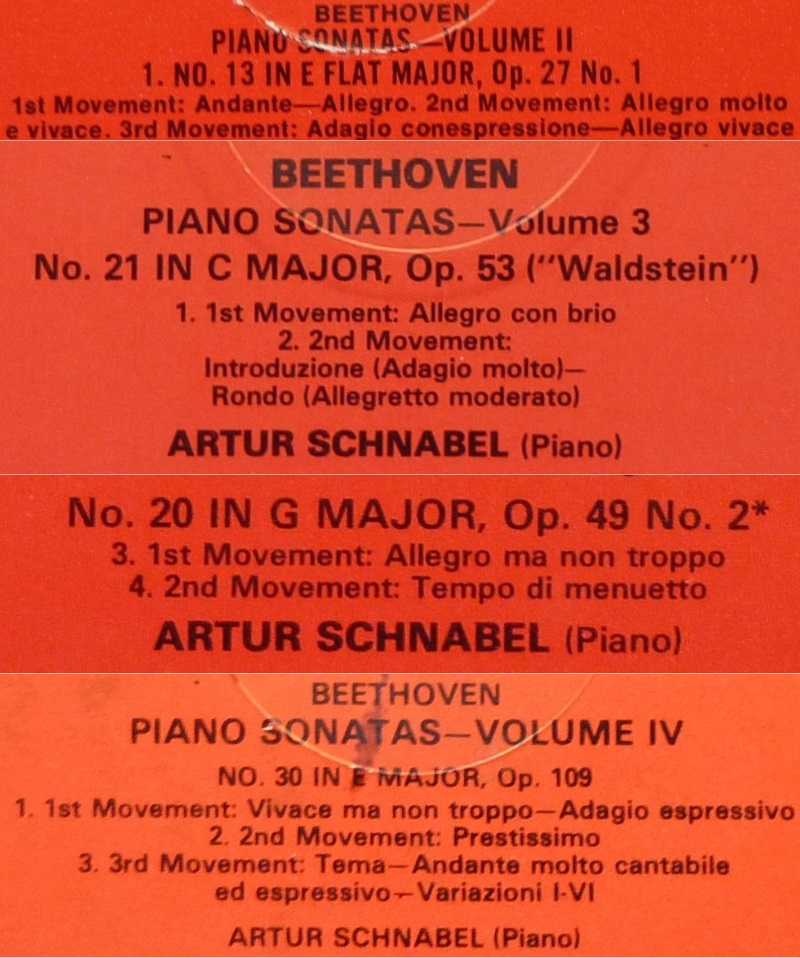

Sonate n°13 Op.27 n°1: 1 Novembre 1932

Sonate n°21 Op.53: 25 Avril & 7 Mai 1934

Sonate n°20 Op.49 n°2: 12 Avril 1933

Sonate n°30 Op.109: 7 Mai 1932

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Schnabel London 1932

Le sixième programme de l’intégrale des 32 Sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel était beaucoup plus court (68′) que le précédent (100′), mais il proposait une très grande Sonate (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) à la fin de chaque partie. La Sonate n°21 Op.53 est la dernière œuvre qu’il a jouée en public (concert du 20 janvier 1951 au Hunter College de New York).

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Une des caractéristiques du jeu de Schnabel, qui n’a pas été soulignée par les critiques new-yorkais, mais que l’on perçoit très bien sur ces reports, est la beauté des pianissimi, remarquables aussi bien par la qualité du timbre que par leur densité de son.

Pour le sixième récital, donné le 19 février 1936 à Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarque que Schnabel a bien rendu le caractère enchanteur et romantique de la sonate en si bémol majeur (n°13 Op.27 n°1) et a joué la modeste sonate en sol majeur (n°20 Op.49 n°2) avec la légèreté et le charme qui conviennent à son expression sans apprêt. ‘Mais, c’est avec les deux autres sonates que Mr. Schnabel était confronté au plus grand Beethoven, et c’est dans celles-ci que ses interprétations avaient l’incandescence et la profondeur dignes du compositeur. Le mouvement qui ouvre la sonate en do majeur (n°21 Op.53) était pris un peu plus rapidement que la plupart des pianistes. La puissance et le joie de vivre de la musique justifient cete option, dans la mesure où une allure impétueuse ne mène pas à rendre confus les passages vertigineux. Ceux-ci, sous les doigts de Mr. Schnabel, n’étaient pas confus. Plus encore, la musique était présentée avec une clarté cristalline, avec des nuances délicates et aucun manque d’enthousiasme et de propulsion. L’Adagio était angoissé dans sa réserve, et le dernier mouvement, comme le premier, était un tour de force d’animation et de lyrisme. Si le Beethoven de la ‘Waldstein’ était communiqué avec tout le brio et l’audace de sa robuste maturité, que dire alors du jeu de Mr. Schnabel dans la sonate en mi majeur (n°30 Op.109), musique dans laquelle Beethoven a atteint une incomparable liberté d’imagination? C’était une interprétation d’une portée incandescente, avec le noble Andante rendu avec émotion. Alors que Mr. Schnabel était arrivé au terme des dernières pages apocalyptiques avec leur mélange de sérénité et de tristesse, l’auditoire est resté silencieux. Il a fallu un moment pour rompre la magie. Et alors Mr. Schnabel reçut un tonnerre d’applaudissements, comme à la fin de la ‘Waldstein’, et comme ça a été également le cas tout au long de ce remarquable marathon.’

The sixth program of Artur Schnabel’s complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 Sonatas was much shorter (68′) than the preceding one (100′), but it offered a very great Sonata (n°21 Op.53 « Waldstein » & n°32 Op.109) at the end of each part. The Sonata n°21 Op.53 is the last work he performed in public (concert of 20 January 1951 at Hunter College in New York).

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

One of the highlights of Schnabel’s playing, not underlined by the New-York critics, but well reproduced on these transfers, is the beauty of the pianissimi, outstanding as to the quality of the timbre as well as to their density of sound.

For the sixth recital given on 19 February 1936 at Carnegie Hall, Howard Taubman remarks that Schnabel captured the enchanting, romantic spirit of the E flat major sonata (n°13 Op.27 n°1) and played the unpretentious G major sonata (n°20 Op.49 n°2) with the lightness and charm that its unashamed sentiment required. ‘But it was in the other two sonatas that Mr. Schnabel had the greater Beethoven to contend with, and it was in these that his interpretations had the incandescence and penetration that where worthy of the composer. The opening movement of the C major sonata (n°21 Op.53) was taken a shade faster than the tempi of many pianists. The power and exhilaration of the music justify this procedure, provided a headlong pace does not cause the vertiginous passages to be blurred. They were not blurred under Mr. Schnabel’s hands. More, the music was set forth with crystalline clarity, with delicate nuance and with no loss of fire or propulsion. The Adagio was anguished in its restraint, and the last movement, like the first, was a tour de force of animation and lyricism. If the Beethoven of the ‘Waldstein’ was communicated with all the gusto and daring of his robust maturity, what is there to say of Mr. Schnabel’s playing of the E major sonata (n°30 Op.109), music in which Beethoven had achieved incomparable freedom of the imagination? It was an interpretation of glowing comprehension, with the noble Andante movingly communicated. As Mr. Schnabel concluded the final apocalyptic pages with their intermingling of serenity and sorrow, the audience remained hushed. It was several moments before the spell was broken. Then, Mr. Schnabel was thunderously applauded, as he was at the end of the ‘Waldstein’, and as he has been throughout this remarkable marathon’.

Extrait du programme du Concert/ From Concert program: Schnabel BBC SO/A. Boult Queen’s Hall 15 February 1933

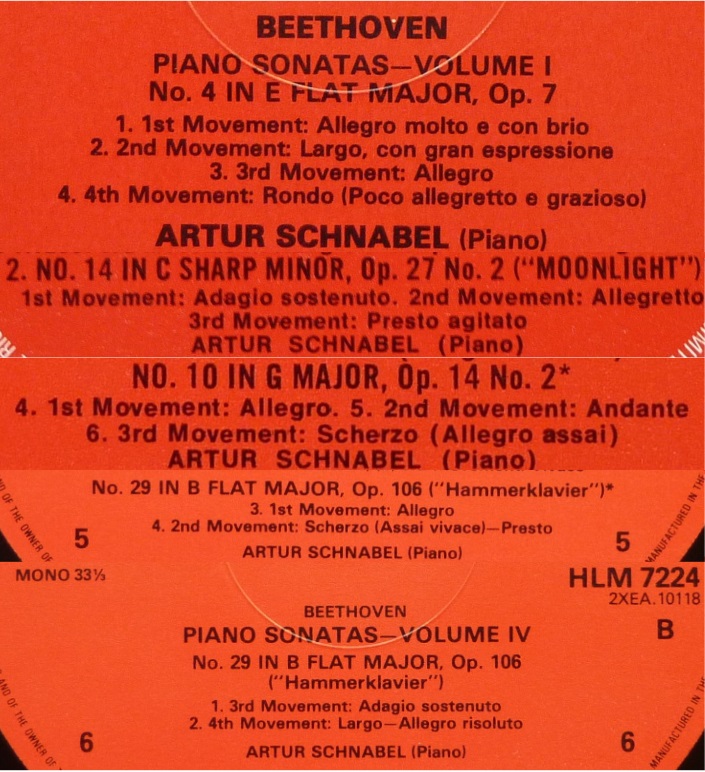

Sonate n°4 Op.7: 11 Novembre 1935; 15 Janvier1937 (face 2)

Sonate n°14 Op.27 n°2: 10& 11 Avril 1933

Sonate n°10 Op.14 n°2: 23 Avril 1934

Sonate n°29 Op.106 « Hammerklavier »: 3 & 4 Novembre 1935

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Les trois derniers récitals de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel en formaient le point culminant. En effet, ils se terminaient chacun par une des dernières sonates respectivement n°29 Op.106, n°30 Op.109 et enfin n°32 Op.111. La sonate n°31 Op.110 a quant à elle été jouée au cours du premier récital.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Le cinquième programme comportait les quatre sonates mentionnées ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert, alors qu’il aurait semblé plus logique de ne jouer que la sonate n°29 Op.106 en deuxième partie. On voit ici le souci de Schnabel d’individualiser au maximum chaque sonate en jouant en début de seconde partie la sonate n°10 Op.14 n°2 dont Eric Blom caractérisait le thème du premier mouvement en disant qu’il pourrait se chanter avec les paroles « O, what a happy day », tout en restant pour la monumentale sonate n°29 Op.106 dans le cadre stylistique qu’il s’était fixé: à un critique qui trouvait que son enregistrement de cette œuvre n’était pas du « grand piano », il a répliqué « it’s big in concept, not in sound » (c’est grand par le concept, et non par le son). Une grande leçon!

Comme les critiques de disque l’ont remarqué, l’Op.106 pose le problème des limites techniques de Schnabel à l’époque de l’enregistrement, d’autant plus qu’il se conforme aux indications métronomiques spécifiées par Beethoven (c’est la seule sonate pour laquelle le compositeur en a fourni). Claudio Arrau a dit que sa technique était parfaite jusqu’à l’arrivée au pouvoir des nazis, qui l’a contraint brutalement à quitter définitivement l’Allemagne, mais que c’est ensuite que les difficultés techniques sont apparues, de même que des trous de mémoire. Si ici, le début du premier mouvement est plutôt chaotique, il semble aussi qu’à la base, il y ait un choix conceptuel aussi génial que délibéré, comme si le discours, incroyablement tendu, émergeait du chaos pour s’organiser progressivement. Schnabel est celui qui ose! D’ailleurs, pour cette série d’enregistrements de novembre 1935, certaines des faces ont été refaites en janvier 1937 pour les sonates n°4 Op.7 & 16 Op.31 n°1, mais pas pour l’Op.106.

Peu après cet enregistrement, Schnabel a joué deux fois cette sonate, tout d’abord à Vienne au Konzerthaus (16 décembre 1935), puis à New-York le 12 avril 1936, le cinquième récital de son intégrale, et pour ces deux exécutions, les critiques ne mentionnent pas de problèmes techniques.

Pour le concert viennois, Herbert Peyser fait état d’un monumental récital Beethoven culminant dans une exécution de l’ ‘Hammerklavier’ apte à pulvériser quiconque aurait proféré des mots irrespectueux envers cet Opus prométhéen, notamment son apothéose fuguée.

Pour le cinquième programme de l’intégrale donnée par Schnabel à Carnegie Hall en 1936, Howard Taubman mentionne que le couronnement de ce récital était l’interprétation de la sonate ‘Hammerklavier’ Op.106 (n°29), une éloquente re-création d’une oeuvre immense, et que les sonates joués avant semblaient pâles en comparaison. ‘L’ ‘Hammerklavier’ se situe sur le même plan que les pages gigantesques des symphonies de Beethoven. Même pour des oreilles modernes, elle sonne audacieuse de par son concept et d’une imagination brillante quant à son exécution, et plus d’un siècle s’est écoulé sans que son originalité prophétique en soit diminuée. Elle demande pour lui donner vie un pianiste qui maîtrise une fusion magistrale de la tête, du cœur et des mains, et Mr. Schnabel était hier soir un tel artiste. Il y avait de la passion et de la puissance dans les deux premiers mouvements de la sonate, et l’interminablement difficile section finale a été rendue avec une maîtrise achevée. Mais c’est dans l’immense mouvement lent – séraphique dans son exaltation et poignant par sa compassion interrogative – que Mr. Schnabel a joué de la manière la plus profondément émouvante de la soirée. Il n’y a à l’étranger pas beaucoup de pianistes capables de rendre justice à ce mouvement. Mr. Schnabel était en forme hier soir et son interprétation des trois sonates précédentes était marquée par une attention caractéristique à la fois pour les détails et pour la pleine conduite du discours d’une œuvre. La sonate en do dièse mineur (n°14 Op.27 n°2), depuis des années la préférée des broyeurs d’ivoire, y trouvait une nouvelle vitalité.’

The last three recitals were the climax of Artur Schnabel’s complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 sonata. Indeed, each of them ended with one of the last sonatas respectively n°29 Op.106, n°30 Op.109 and finally n°32 Op.111. Sonata n°31 Op.110 was played separately at the first recital.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

The fifth program was comprised of the four above mentioned sonatas, the first two of which being played before the intermission, whereas it would have been more logical to play only the sonata n°29 Op.106 at the second part of the recital. This reflects Schnabel’s concern to individualize each sonata to the utmost by playing at the beginning of the second part the sonata n°10 Op.14 n°2 of which Eric Blom caracterized the thema of the first movement by saying it could be sung to the words « O, what a happy day », while remaining for the monumental sonata n°29 Op.106 in the stylistic frame he decided: to a critic objecting that his recording of this work was not « great piano », he replied « it’s big in concept, not in sound ». A great lesson!

As music critics have noticed, Op.106 poses the problem of Schnabel’s technical limits at the time of the recording, all the more so since he applies Beethoven’s metronomic markings (it is the only sonata for which the composer provided them). Claudio Arrau said that his technique was flawless until the nazis came to power, which brutally obliged him to leave Germany, but thereafter, technical difficulties started and also memory mistakes. If here the beginning of the first movement is rather chaotic, it seems also that basically this was a chosen concept as full of genius as it was deliberate, as if the incredibly tense musical flow emerged from chaos to organize itself progressively. Schnabel is the one who dares! Indeed for this series of recordings of November 1935, a few sides were re-recorded in January 1937 for the sonatas n°4 Op.7 & 16 Op.31 n°1 but not for Op.106!

Shortly after this recording, Schnabel performed this sonata twice, firstly at the Vienna Konzerthaus (16 December 1935), then on 12 April 1936, the fifth recital of his complete performance of the ’32s’, and in both cases, music critics do not mention at all technical problems.

For the Viennese concert, Herbert Peyser speaks of a monumental Beethoven recital culminating in a performance of the ‘Hammerklavier’ which must have pulverized any one who ever spoke a disrespectful word of this Promethean Opus, particularly of his fugal apotheosis.

For the fifth program of the complete performance given by Schnabel at Carnegie Hall in 1936, Howard Taubman mentions that the pinnacle of the recital was the performance of the B flat major Sonata Op.106 known as the ‘Hammerklavier’, an eloquent recreation of an immense work, and that the sonatas that had gone before seemed pale in comparison. ‘The ‘Hammerklavier’ is on the plane of the gigantic pages of Beethoven’s symphonies. Even to modern ears, it sounds audacious in design and brilliantly imaginative in execution; more than a century of currency has not dimmed its prophetic originality. It requires a pianist who commands a superb fusion of head, heart and hands to bring this sonata to life, and Mr. Schnabel was such an artist last night. There was passion, power and a broad line in the first two movements of the sonata, and the endlessly difficult final section was wrought with consumate ressource. But it was in the tremendous slow movement – seraphic in its exaltation and poignant in its searching compassion – that Mr. Schnabel did the most profoundly moving playing of the evening. There are no many pianists abroad who can do justice to this movement. Mr. Schnabel was in the vein last night and his interpretations of the three earlier sonatas were marked with a characteristic regard both for detail and the full sweep of a work. The C sharp minor Sonata (n°14 Op.27 n°2), for years the favorite of any keyboard pounder, assumed a new vitality.’

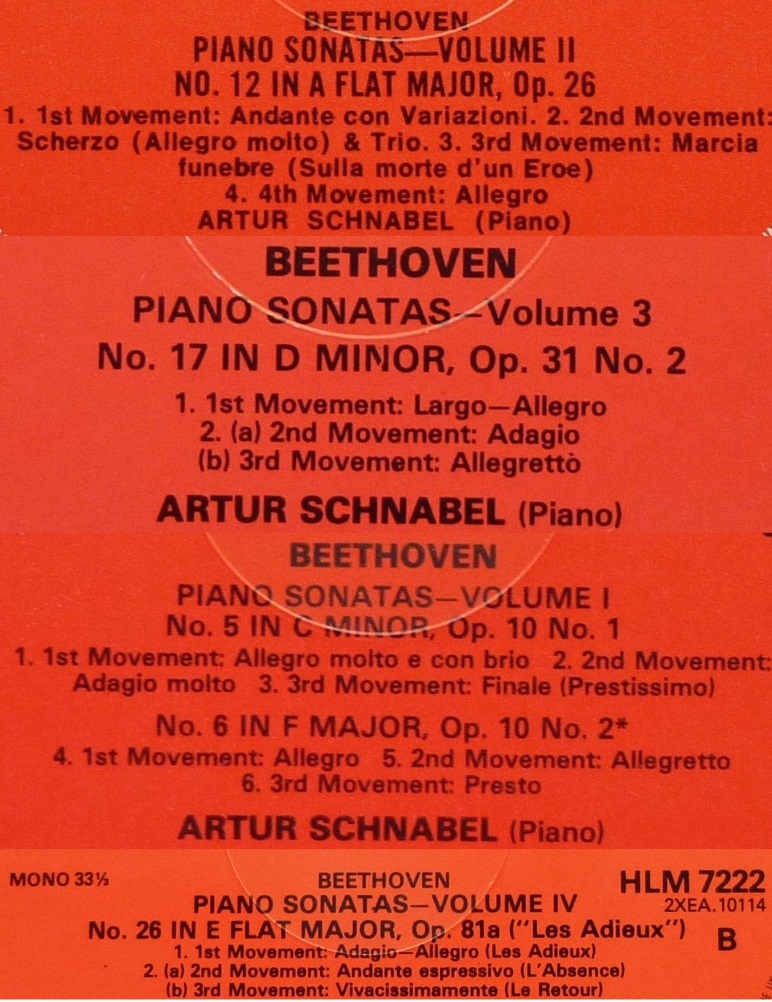

Sonate n°12 Op.26: 25-27 Avril & 4 Mai 1934

Sonate n°17 Op31 n°2: 27& 28 Avril 1934

Sonate n°5 Op.10 n°1: 6 Novembre 1935

Sonate n°6 Op.10 n°2: 10 Avril 1933

Sonate n°26 Op.81a: 13 Avril 1933

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n°3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le quatrième programme de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comportait les cinq sonates mentionnées ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Pour le quatrième programme de l’intégrale donnée par Schnabel à Carnegie Hall en 1936, Olin Downes souligne tout d’abord que le plus grand mérite de Schnabel est de démontrer une fois pour toutes au public de cette ville l’immense variété de contenu qui se trouve dans tout groupe de quatre ou cinq sonates de Beethoven, d’autant plus qu’il a la sagesse de les jouer, non par ordre chronologique, mais d’opposer des sonates de ‘styles’ et d »époques’ différentes d’une manière à la fois évocatrice et divertissante. » C’était également le cas hier soir, bien que Schnabel ait été d’humeur inégale. Dans la sonate en la mineur op.26 (n°12) qui ouvrait le programme avec un mouvement en variations, l’énoncé du thème était exagéré quant au style, le son était dur et l’interprétation était didactique et autoritaire. La sonate était au-delà du tempérament de l’exécutant, sans qu’on puisse du tout en déduire que Mr. Schnabel, en dépit de son objectivité et de son analyse, soit un interprète purement objectif. C’est même tout le contraire! Et il l’a prouvé dans l’interprétation suivante, celle de la sonate en ré mineur (n°17 Op.31 n°2) au dramatisme orageux, qui dans l’ensemble était la plus grande réussite de la soirée. Dans le premier mouvement qui pourrait bien porter comme spécifié pour d’autres sonates du compositeur, le sous-titre ‘quasi una fantasia’, il y avait du drame , presque du théâtre, sous sa forme la plus passionnée. Le chant dans l’Adagio, mouvement noblement proportionné, aurait pu être plus simple. Le Finale était puissamment conduit avec un sentiment romantique, et Mr. Schnabel a clairement montré que si ses motifs sont ostensiblement banaux, son expression est intense et agitée. Il s’est ensuite consacré à l’humour et à l’imagination de la sonate en do mineur Op.10 n°1 (n°5) ainsi qu’à une autre sonate, virile et joyeuse et elle aussi d’une veine plus légère, celle en fa majeur Op.10 n°2 (n°6) avec un ‘Scherzo’ (Allegretto) qui rappelle les hésitations du mouvement correspondant de la Cinquième Symphonie et son merveilleux trio. Les deux premiers mouvements, en particulier le deuxième étaient beethovéniens jusqu’à l’âme et si sans doute le Finale doit être très rapide, cela ne doit pas interférer avec la clarté comme cela a été le cas hier soir, où la clarté qui est une des vertus cardinales de Mr. Schnabel n’était pas toujours présente. Pour finir, c’était la sonate « Les Adieux » (n°26 Op.81a), « romantique » quant à son expression, mais dans une certaine mesure prophétique de développements modernes de la musique, et à cause de cela surestimée par ceux pour qui Beethoven ne saurait se tromper. Mais ici Mr. Schnabel est allé loin dans la révélation de la plénitude de la pensée de Beethoven, là où l’intuition ainsi qu’une profonde connaissance sont requises de l’exécutant. Le public a écouté avec dévotion et a tout applaudi frénétiquement ».

Le lendemain de ce concert, commençait au Metropolitan Opera le Cycle Wagner (6 février – 5 mars) donné chaque année avec le Ring et les Meistersinger dirigé par Artur Bodanzky et une distribution de rêve.

The fourth program of the complete performance of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas by Artur Schnabel was comprised of the five above mentioned sonatas, two of which being played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

For the fourth program of the complete performance given by Schnabel at Carnegie Hall in 1936, Olin Downes points out that, had Mr. Schnabel accomplished nothing else for the benefit of the public of this city, he would have demonstrated once and for all the immense variety of matter and of mood that any four or five of the thirty-two Beethoven sonatas contain. » He has had the wisdom, in program-making not to play these works in their historic sequence, but to contrast sonatas of different ‘periods’ and ‘styles’ in a way that is highly suggestive and entertaining… This was realized anew last night although Mr. Schnabel appeared to be in an uneven mood. He began with the A-flat sonata Op. 26 (n°12) which opens with variations. The announcement of the theme was exaggerated in style; tone most of the time was hard; there was a didactic and overbearing manner of interpretation.. The sonata apparently was outside the performer’s mood, and let no one think that Mr. Schnabel, for all his objectivity and analysis, is a purely objective player. Quite the contrary! He proved this in the performance that followed, which on the whole was the finest achievement of the evening. The sonata was the one in D minor (n°17 Op.31 n°2), stormily dramatic, a sonata which, like others so specified by the composer, could well bear the title in the first movement of ‘quasi una fantasia’. This was drama, almost theatre, of the most impassioned sort. The Adagio, nobly proportioned, could have been sung more simply. The Finale was given a powerful drive and again, dramatic feeling. Ostensibly trivial in its motives, it is actually a very expressive and agitated utterance, as Mr. Schnabel made clear. He turned then to the humor and fancy of the C minor sonata (n°5 Op.10 n°1) and to another sonata, virile, jocose, also in a prevailingly lighter vein, the one in F major Op.10 n°2 (n°6) with the ‘Scherzo’ (Allegretto) remindful of the gropings of the corresponding movement in the Fifth symphony, and the wonderful trio. The first two movements, especially the second, were Beethoven to the core. No doubt the finale should go very fast, but not so fast as to interfere with clearness, which was the case last night, when clearness, one of the cardinal attributes of Mr. Schnabel’s playing was not invariably in evidence. The end came with ‘Les Adieux’ sonata (n°26 Op.81a), ‘romantic’ in expression, prophetic in certain measures of modern musical developements, for all that a sonata overrated by those for whom Beethoven can do no wrong. But here, Mr. Schnabel went far to reveal the completeness of Beethoven’s meaning, in measures where divination as well as profound knowledge on the part of the performer is required. The audience listened devoutly. Everything that was done was rapturously applauded. »

The day after this concert, the annual matinee Wagner Cycle (February 6 – March 5) conducted by Artur Bodanzky began at the Metropolitan Opera with the Ring and Die Meistersinger and a dream cast.

Sonate n°2 Op.2 n°2: 9 Avril 1933

Sonate n°23 Op.57: 11 Avril 1933

Sonate n°19 Op.49 n°1: 19 Novembre 1932

Sonate n°27 Op.90: 21 Janvier & 3 Février 1932

Sonate n°11 Op.22: 12 & 13 Avril 1933

Artur Schnabel, piano

London Abbey Road Studio n° 3 – Engineer: Edward Fowler – piano: Bechstein

Source: disques 33 tours « The HMV Treasury »

Le troisième programme de l’intégrale des 32 sonates de Beethoven par Artur Schnabel comportait les cinq sonates mentionnées ci-dessus, dont les deux premières ont été jouées en première partie de concert.

Pour plus de détails sur les sept récitals de cette intégrale, cliquer ICI

Pour le troisième programme de l’intégrale donnée par Schnabel à Carnegie Hall en 1936, Howard Taubman souligne que la simplicité et la ré-utilisation de moyens mis en oeuvre par d’autres compositeurs dans la sonate en la majeur Op.2 n°2 mettent en valeur l’audace et l’originalité de la pensée de Beethoven dans l’ « Appassionata » qui pour une fois n’est pas « interprétée », Schnabel semblant laisser Beethoven parler pour lui-même en libérant toute sa puissance, tout en maintenant l’oeuvre dans les limites du piano. « Il n’a pas donné l’impression que cultivent certains virtuoses qu’il pourrait obtenir on ne sait quels prodiges avec un instrument de plus grande ampleur. En jouant l’une après l’autre les sonates en sol mineur (Op.49 n°1) et en mi mineur (Op.90), Schnabel a montré qu’elles étaient plus proches que le simple fait d’avoir le même compositeur avec des ressemblances et des différences, la première étant calme, romantique et directe, et la deuxième, claire profonde et pénétrante. Et enfin, la sonate en si bémol majeur (Op.22), moins exigeante pour l’auditeur, terminait la courbe claire et ample du programme ».

Il est intéressant à ce point pour approfondir cette analyse du style d’interprétation d’Artur Schnabel par les critiques musicaux Olin Downes et Howard Taubman de se référer au magnifique texte de Claudio Arrau publié en 1952 sous le titre « Artur Schnabel Servant of the Music » (« Artur Schnabel Serviteur de la Musique ») et qui est pour l’essentiel consacré aux Sonates de Beethoven et à son message humaniste:

« Dans mon souvenir de la manière dont Schnabel jouait Beethoven, deux choses me viennent particulièrement en mémoire: sa compréhension du caractère global de chaque sonate et son traitement admirable des mouvements lents. Avec toutes les sonates, depuis la toute première—dans laquelle Beethoven est déjà Beethoven et aussi un maître, et qui de ce fait est entièrement achevée à la fois par sa forme et sa construction et par son caractère essentiel — jusqu’à l’ultime Op. 111, où Beethoven est le prophète qui transcende tout le combat humain, Schnabel est devenu lui-même un prophète par sa compréhension des détails des parties qui les constituent et de la somme totale de cette littérature colossale.

A une époque où jouer vite semblait souvent être le seul but de la virtuosité pianistique, Schnabel n’en avait cure et il montrait son courage en jouant vraiment lentement les mouvements lents. Renforcé par sa conviction et par sa concentration, il les jouait plus lentement que quiconque ne l’avait jamais imaginé possible. Et sa manière de ralentir encore plus à la fin de tels mouvements était absolument inoubliable, un ralentissement qui créait une atmosphère dramatique et une tension qui étaient à la fois impressionnantes et uniques. C’était la preuve d’un profond calme intérieur que la plupart des musiciens n’atteignent que tard dans leur vie, voire jamais, mais qu’il possédait à un rare degré depuis le début. . . .

Son interprétation de l’Opus 54 (sonate n°22) montre qu’il ne suivait pas aveuglément sa propre édition et ses indications, mais se donnait la liberté de suivre l’inspiration du moment. Il maintenait à un rare degré à la fois un équilibre des moyens pour faire les choses comme il les concevait et un équilibre entre l’intellect et l’émotion intuitive. Beaucoup d’artistes ont soit l’un, soit l’autre de ces dons. Mais chez Schnabel il y avait une synthèse remarquable de savoir, d’intelligence, d’intuition, d’émotion et de moyens techniques. L’importance en tant qu’artiste de Schnabel vient de l’importance du message de la musique de Beethoven. Avec les trente deux sonates, Beethoven a créé tout un univers. Dans leur globalité, elles forment une immense épopée du combat de l’humanité et de sa souffrance et de la victoire ultime de l’esprit. Fait unique, Schnabel était un homme et un artiste à la hauteur de toutes les exigences de cette stupéfiante effusion de génie.

Dans les dernières sonates, Beethoven a développé un langage pour les initiés, un langage dont le caractère symbolique et ésotérique n’a jamais été surpassé dans aucune autre œuvre d’art antérieure ou postérieure. C’est parce que Schnabel était un des rares initiés qui comprenaient et parlaient ce langage qu’il était capable de rendre le Beethoven de cette période plus proche de la compréhension contemporaine. Il n’y a pas de plus grande réalisation qu’un artiste puisse accomplir. »

Claudio Arrau

____________

Artur Schnabel’s third program of the complete Beethoven sonatas was comprised of the above mentioned five sonates, two of which being played before the intermission.

For a detailed description of the seven programs of his complete performances of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, click HERE

For the third program of the complete performance given by Schnabel at Carnegie Hall in 1936, Howard Taubman underlines that the simplicity and untroubled iteration of other composer’s devices of the early sonata from the Op.2 series (Op.2 N°2) were ideal foils for the audacity and originality of Beethoven’s thinking in the « Appassionata » for which Mr. Schnabel seemed to let Beethoven speak for himself with all its surging power, while keeping the work within the piano’s limitations. « He did not give the impressions cultivated by some virtuosos what wonders they could work with an instrument with greater scope. The G minor (Op.49 n°1) and E minor (Op.90) sonatas placed besides each other, appear to have a closer relationship than the obvious one of stemming from the same progenitor. Mr. Schnabel indicated their closeness and disparity – the former: cool, romantic, direct; the latter: clear, profound, penetrating. And finally the B flat major sonata (Op.22), less exacting in its demand on the listener and providing the end of the program’s clean, sweeping curve ».

It is interesting at this point to deepen this analysis of Artur Schnabel’s style by music critics Olin Downes and Howard Taubman, to revert to the magnificent text by Claudio Arrau published in 1952 under the title « Artur Schnabel Servant of the Music » and essentially dealing with the Beethoven Sonatas and their humanist message:

« Remembering how Schnabel played Beethoven, two things particularly stand out in memory: his grasp of the whole character of every sonata and his divine way with the slow movements. With all the sonatas, from the very first one—in which Beethoven is already Beethoven and a master, and which is therefore entirely definite both in shape and construction and in essential character—to the final Op. 111, where Beethoven is the seer transcending all human struggle, Schnabel became a seer himself in his grasp of the component details and the sum total of this colossal literature.

In a period when playing fast often seemed to be the sole goal of piano virtuosity, Schnabel paid no heed and showed his courage by making the slow movements really slow. Strengthened by conviction and concentration, he played them slower than anyone else had even imagined to be possible. Absolutely unforgettable was his way of slowing down still more at the end of such movements, a slowing-down that created a dramatic atmosphere and tension that were both impressive and unique. This was evidence of a deep, inner repose that most musicians attain only latc in life, if ever, but that he possessed to a rare degree from the beginning. . . .

His performance of Opus 54 shows that he did not follow his own edition and markings slavishly, but gave himself freedom to follow the inspiration of the moment. To a rare degree he maintained both a balance of the means required to do things as he conceived them and a balance between intellect and intuitive emotion. Many artists have one gift or the other. But in Schnabel there was a remarkable synthesis of knowledge, intelligence, intuition,emotion and technical means. Schnabel’s importance as an artist stems from the importance of the message of Beethoven’s music. In the thirty-two sonatas Beethoven created a whole cosmos. In their totality, they form an immense epic of man’s struggle and suffering and ultimate victory of the spirit. Schnabel, uniquely, was man and artist enough to meet all the demands of this staggering outpouring of genius.

In these last sonatas Beethoven developed a language for the initiated, a language of a symbolic and esoteric character never more strongly pronounced in any works of art before or since. Because Schnabel was one of the few initiated who understood and spoke this language he was able to bring the Beethoven of this period nearer to contemporary comprehension. No greater realization could come to any artist. »