Artur SCHNABEL – AUSTRALIAN TOUR 1939 PART II: Concerts n° 12 –27 (June 20 – August 16)

ADELAIDE, SYDNEY, MELBOURNE, CANBERRA, PERTH

After his fifth and last recital in Sydney, and a very welcome one-week pause, Schnabel gave three concerts in Adelaide before going back to Sydney for an orchestral concert with Szell, and then to Melbourne for four recitals.

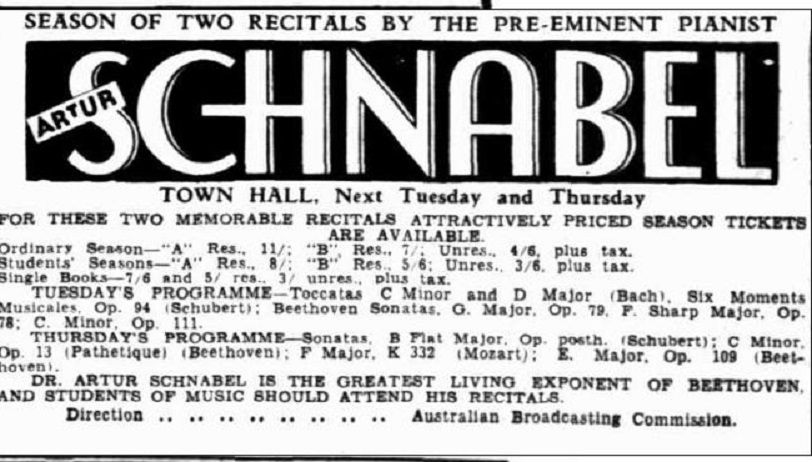

12- June 20 ADELAIDE Town Hall Program 4

BACH Toccata C Minor BWV 911 & D Major BWV 912 – SCHUBERT Moments Musicaux Op.94 D780

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°25 Op.79 – Sonata n°24 Op.78 – Sonata n°32 Op.111

Advertiser (June 21): ‘To those so-called musical purists who are afraid to pedal Bach, Schnabel provides a useful lesson in his subtle and effective use of the damper pedal for coloring, sustaining as in sonorities, and obtaining a warm legatissimo which avoids that suggestion of brittle passage playing we sometimes hear in Bach. The opening number, Toccata in C Minor (Bach) was virile and meditative by turns. Its fugue flowed smoothly with no exaggeration of its subject matter, although every entry of subject or answer was announced with perfect clarity. With consummate discretion, this pianist reverses his use of rubato for those movements of Bach which do not call for rhythmical insistence. An outstanding example was the utter freedom of mood expressed in the « adagio » and recitative sections of the Bach D Major Toccata, his second offering. Its final movement, with its fascinating rhythmic qualities, showed the recitalist in happy humor. His masterly part-playing, and contrast of tonal qualities gives to his performance of Bach a wealth of musical significance. Schnabel, who loves to delve into the lesser known compositions of his favorIte composers, has discovered many hidden beauties in their style. The simple yet lovely Moments Musicaux Op.94 (Schubert) were given that tender poetic expression which they call for. Melodic phrases of ineffable charm, which might easily have been a little too square in treatment, were dwelt upon just long enough to be appreciated and absorbed by the listener and carried away as a rare memory. No facet of Schubert’s genius is missed by this understanding interpreter. Sonata in G Major. Op. 79 (Beethoven), with its gay opening movement, provided a somewhat lighter interlude to the programme. Schnabel, who never strains after effect, made no more of this slight work than there is in it. A dash of sentiment in the andante, and a facile performance of the final vivace, showed effortless technical ease. This unproblematic sonata, written in the condensed dimensions of a sonatina, was followed by Sonata in F Sharp Major, Op. 78, a two movement work which expresses only joy and gaiety. Very complete in the fullness of its expression, at times dazzling in its technical brilliance, this performance aroused spontaneous applause. It was in Beethoven’s great final sonata in C Minor. Op.111 that Schnabel rose to his greatest heights. His magnificent opening of the first movement, his titanic chords, scintillating scale passages, lovely tonal gradations and stupendous contrasts made the performance one of the greatest musical events in the history of this city. That Adelaide music lovers should have been privileged to hear the greatness of Schnabel in his prime is a thing which calls for an expression of gratitude. These reflections were prompted by his playing of the second movement, the spiritually exalted outpouring of Beethoven in his final offering in this form’.

13- June 22 ADELAIDE Town Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Advertiser (June 23): ‘In the in B flat. Op. posth. » (Schubert), making use of a « kunst pause, »‘ or what we might describe as an art pause, Dr. Schnabel isolated the opening theme of its first movement « molto moderato. » This was one of several such uses of pausation which gave the impression of breathing moments for artist and audience, allowing the completed phrase to be absorbed and musically digested before announcing the next. This movement, with its wide dynamic range, included the most subtle pianissimos, contrasted with fortissimos which had the compelling effect of clarion calls. Magnificent music, elevated with its nobility of expression, it provided an ideal opening number for the programme. « Andante sostenuto. », the second movement, with its exquisite poise, the Scherzo, ‘Allegro vivace con delicatezza’ with its innate grace and charm, and the final ‘Allegro ma non troppo » almost ingenuous in its thematic simplicity, were each interpreted with perfect understanding of their respective requirements. The lyrical beauty of Schubert and his restful quality of repose – leaving the listener beatifically unconscious of the passing of time – has surely, never found a more perfect exponent than Artur Schnabel. The opening movement of Beethoven’s « Sonata in C minor. Op. 13 » (Pathetique) ‘Grave-Molto allegro e con brio’ was fraught with an element of tragic plaint, rather than the pathetic questioning which it is so often made to express. Virility was its keynote, Unbroken rhythm was its burden. This impersonal, but powerful, quality was replaced in ‘Adagio cantabile’ by a mood which suggested a quiet intimacy of communion with one’s fellow being. The final ‘Allegro’ was brilliant and exhilarating. In the « Sonata in F major, K332 », Dr. Schnabel was the erudite, polished player, whose grip on essentials was always apparent. Perfect dynamic gradations, elegance of style, contrast of tonal values, crystalline clarity of passage work, particularly in the final « Allegro assai » were characteristics of a flawless performance. Above all else Mozart « lives, » in the hands of Schnabel, and a robust quality, which he uses where required, adds a note of strength to this stylistic genius. Schnabel hardly deviates a hairsbreadth from the printed copy, unless we except his rhythmic rubato. In the sudden transition from the initial « Vivace, ma non troppo' » to an unexpected « Adagio espressivo » in « Sonata in E, Op. 109 » (Beethoven), most pianists cannot avoid the temptation to become a little startling in their effect. Not so with Dr. Schnabel, who avoids such exhibitions of vulgar virtuosity as he would a pestilence. Again, proving his perfect accord with the spiritual message of Beethoven in his final period of maturity, Schnabel « held » his audience through this advanced work which makes no concession to what might be described as popular taste. It follows its own plan, untramelled by any other thought than the complete expression of its composer’s exalted mood. In a letter to Frau Streicher, Beethoven wrote: ‘Today is Sunday. Shall I read something for you from the Gospels? ‘Love ye one another’. It is this conception of serene happiness which we felt at the end of Schnabel’s performance of the Opus 109’. Brewster Jones

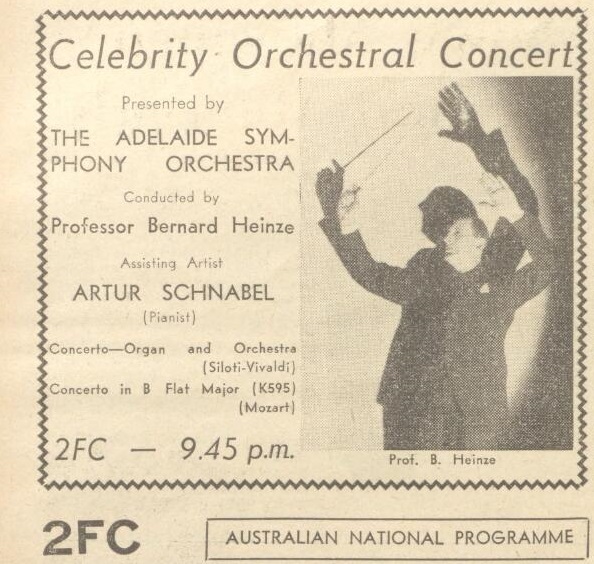

14- June 24 ADELAIDE Town Hall

Adelaide SO dir:Bernard HEINZE

MOZART Concerto n°27 B Flat Major K595

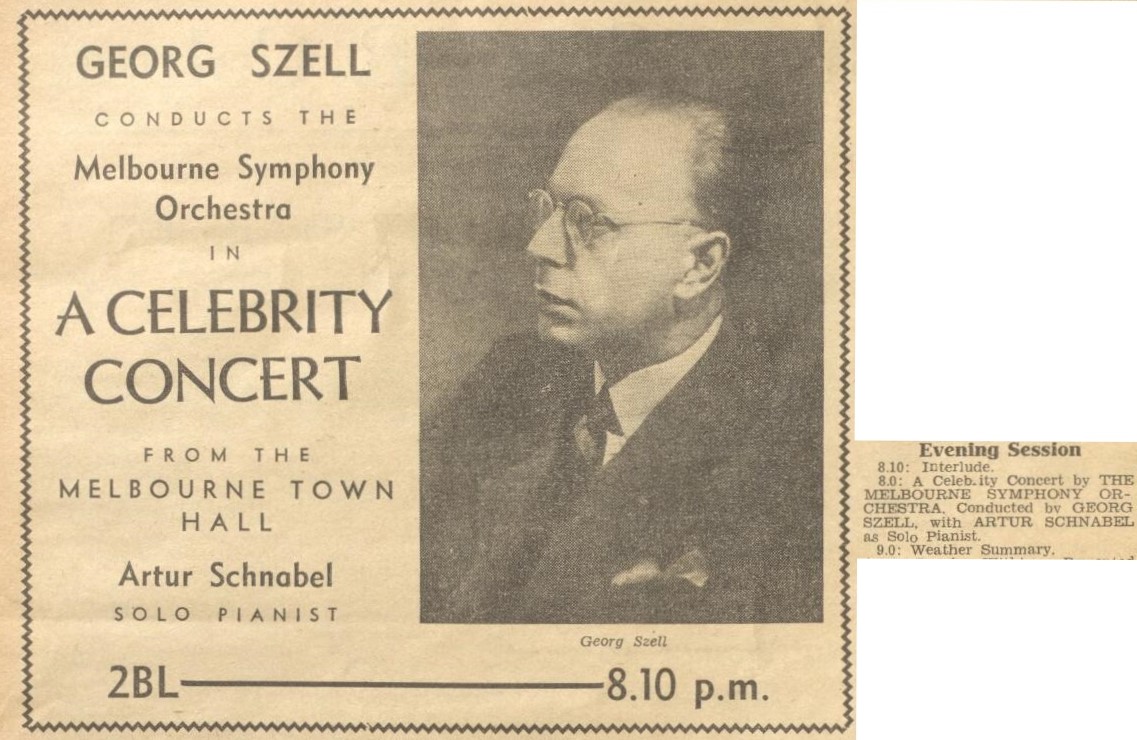

15- June 28 SYDNEY Town Hall

Sydney SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEETHOVEN Concerto n°5 Op.73

Sydney Morning Herald (June 29): ‘Through his lucid yet never rigid manner of playing, Schnabel opens to view the ultimate simplicity of the music. One had known beforehand, approximately the mode of attack he would bring to bear on the ‘Emperor’. Yet the actual revelation seemed perpetually surprising and refreshing. Schnabel can make even a repeated scale in octaves seem a musical adventure of redoubtable magnitude. Some of his playing last night was forceful and resplendent, some hauntingly delicate in its pale traceries of tone. But whatever he did, he did with no apparent physical effort. He seemed to be meditating aloud rather than building up a preconceived plan. The orchestral players provided many passages of beauty in the course of a generally well judged accompaniment. The opening melody of the slow movement for example was enchanting in its tenuous muted sweetness. The players, who were headed as usual by Mr. Lionel Lawson had not yet drawn together again into the full unity and coherence which Professor Szell had exacted toward the end of his previous visit. Schnabel’s utterly crystalline quality sets an exacting standard, and bv contrast some of the orchestral work last night tended to drag’.

Letter (from Sydney) to Mary Foreman (June 29): ‘My concerts, fifteen so far, meet striking response. Houses always crowded. Musical public life here is in its infancy… Music, as a value of its own, begins only to enter. They have not yet one permanent orchestra, but already five composed partly of amateurs, some founded only three years ago. The willingness is promising and astonishing are already the results. The state-controlled broadcasting, for which the subscribers pay, has the entire merit of this rapid developement’; and in another one, also from Sydney (July 3), he wrote: ‘Tonight, I start for my Melbourne recital session (as they call here appearances in each town), four recitals in one week; after my return on the 13th three more concerts here with the orchestra. It depends entirely on the developement in Europe where and when I go from here’.

16- July 5 MELBOURNE Town Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Age (July 6): ‘In the sonata op.110, Beethoven covered a great range of ideas. Schnabel is known as an intellectual. But if an artist is not instantly active in sensitiveness, there is little to put into his framework. The pianist fused his mental forces to give a comprehensive exposition of the sonata. Clarity goes along with Schnabel’s technique, and the cumulative effect, built up from the lambent first movement, and through the sharp and terse molto allegro, came to the utmost expressiveness, in the dolent arioso; while the fugue, as imaginative as ingenious, flood-lit the whole with seraphic illumination. The Waldstein sonata, ‘the C major of Life’, also received a lucid exposition. The enchantment was greater in this work, or more readily felt by some, its fabric being less involved, while its charm is throughout irresistible. The applause following the sonatas proved how greatly the music and the inimitable playing had impressed the listeners. Schnabel has taken Schubert to his heart, testifying to his joy in the miracles of ‘the most poetical of all the musicians’. As the artist cherished them while under his hands, the Four Impromptus, mirroring the soul of a pure spirit, brought the truly great Schubert to life. Mozart, akin to Schubert in the power to create imperishable music, was represented by the A minor sonata, of which a magically finished version of the quick movements was given. The Andante was less impressive’.

17- July 7 MELBOURNE Town Hall Program 5

SCHUBERT Sonata n°20 in A Major D959

WEBER Sonata n°2 A Flat Op.39

SCHUMANN Davidsbündlertänze Op.6

Age (July 8): ‘Dr. Artur Schnabel gave his second recital in the Town Hall last night to a large audience, in which most musicians of Melbourne were found. Schnabel’s control of the keyboard is sufficient for all need. The pianist appears to have no technique, so easy and relaxed is he in his movements. His free arms, supple wrists and fingers that intelligently weigh and measure, are such obedient servants that, impediments swept out of the way, the soul of the musician is free to express, with creative spontaneity, the content of the works he may have in hand. Technical equipment attracting no attention, the listener is the more able to concentrate on the music itself. Schnabel has made the world his debtor in bringing the marvellous beauties of Schubert to the fore. Pianists themselves must be blamed for the master’s neglect. The posthumous sonata in A is symphonic in wealth of ideas and richness, of fancy and feeling. The finely spirited performance, so extraordinarily instinct with vivacious thought, gladdened the heart and mind of every musical listener. Similarly revealing, though with different complexion and meaning, was the A flat sonata of Weber. The music had as much excitement, as the Schubert work, but less depth. All that it contained came out in the artist’s performance. It was Schnabel’s pleasure to treat every phase of the sonata with consummate skill. The characteristics and colors of Schumann’s Davidsbundler were very stimulating. Schnabel seemed to reflect completely the rapidly changing conceits and fleeting ideas of Schumann’s imagination. The highest effectiveness was given to the set, poetic Impulse and romantic energy ruling throughout. Schumann said of his Davidsbundler creation that it figured an intellectual brotherhood that he hoped would bear golden fruit. Of that brotherhood Schnabel is an ardent member, a fit exponent of romance at its best’.

The Herald (July 8): ‘Schnabel’s technique is never set in the forefront, but is completely at the service of his searching mind, and his mind is entirely pre-occupled with the musical thought of the works he is playing. The result is that his technique adapts itself to the style of the composer, instead of the style being twisted, as often happens, to suit the technique and temperament of the pianist. J. E. Tremearne

18- July 10 MELBOURNE Town Hall Program 3

BEETHOVEN Sonate n°3 in C Op.2 n°3

BEETHOVEN Sonate n° 17 in D minor Op.31 n°2

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.90 D899

SCHUBERT Sonate n°17 D Major Op.53 D850

Age (July 11): ‘Beethoven’s early Sonata in C offered opportunity for display, which the artist, while brilliant, kept within limits. The allegros were finely spontaneous and free; the adagio came as a resting time of tranquil pleading. The light-hearted rondo, with its staccato 6ths, rippled and danced to its coda without indulging in the boisterous humor of later Beethoven days. The dramatic D minor sonata, opening with sterner material, also found its reflective mood in the Adagio. Its eloquent meditation was not forgotten when the cantering lilt of the moto perpetuo brought the work to a close. Coming to Schubert, the Op.90 Impromptus revealed Schnabel’s sympathy with pure lyricism, which he expressed in precise, but exquisitely fluent, terms. The audience could not help but sing in spirit with Schubert’s engaging themes. The festive D major sonata has something of the impetuosity of the C major symphony. Its vigor and tunefulness are unceasing. Schnabel possessed the sprightly fancy to meet the ebullient imagination of Schubert, with the result that many marvelled that the master is so seldom heard, except for a few favorite Lieder. The captivating rondo, with its bewitching melodic grace, closed an evening of great music and uplifting experiences.

19- July 11 MELBOURNE Town Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Age (July 12): ‘Dr. Schnabel gave his final recital in the Town Hall last night. Very reluctant was the audience to part with an artist so universally esteemed. The master pianist has very human qualities. The B flat posthumous sonata of Schubert, copious in extent, rich in motives, and ever-quickening elation, made a majestic opening. Schubert never holds inspiration in reserve. All is frank and open. Whims, tears and an exuberant joyance flood his pages. Never is he feeble, nor redundant with all his repetitions. Schnabel saw that nothing of Schubert would be lost to the audience. It will be strange if the demand for more Schubert at our concerts is not forthcoming. Beethoven’s « Pathetic » sonata, every note of which is known to musicians, was played with serious and urgent emphasis, almost inking on the depth of a later opus, so impressively did Schnabel bring out its passion and the hopeful contentment of the rondo. The Mozart sonata is very direct in its statements, yet it is a pliable mind that captures the master’s best. Mozart is acquired intuitively. His spontaneity, grace and poise are to be possessed by the interpreter in a similar degree to that which the composer himself possessed them. Some have preferred Schnabel’s Beethoven to his Mozart and Schubert to his Beethoven. Others would draw no fine distinction. The audience listened with the closest attention to Beethoven’s Op.109, a leave-taking into which Schnabel put all his heart, and in which the audience felt all its gratitude. Here, perhaps, were the most momentous and imperishable impressions of Schnabel’s personality and art. From the semi-rhapsodic opening to the elaborate variations, all could catch a semblance of the Beethoven rapture. The brilliant coda declined in radiance when the initial touching theme returned to close a transcendent experience in tranquil repose. Ovations followed each of Schnabel’s performances throughout his historic season’.

In this very important letter to Mary Foreman (Sydney July 15), Schnabel wrote: ‘In all probability, I shall go back to Europe (if at all) via the USA instead of taking, as originally intended and booked, the Suez route. The danger of war remains acute, and to be (possibly) kept and caught somewhere in the Indian sea is rather risky, thus I decided to choose the comparatively safer way and to stay in case of the worst coming true in America. I shall leave on August 18th with the SS Monterey from Sydney, and arrive in Los Angeles September 4th’. In this letter, Schnabel also mentions the unexpected marriage of his second son, Stefan: ‘Stefan surprised us with his marriage, announcing it with a telegram to us, asking for the parents’ blessing, the message also signed with the first name of his wife (Joan). I have never seen the girl. Stefan has been wanting to marry for a long time, has known intimely several candidates whom after a while he dismissed all as not suited. I have to make the best of it and be confident and helpful as long as it goes’.

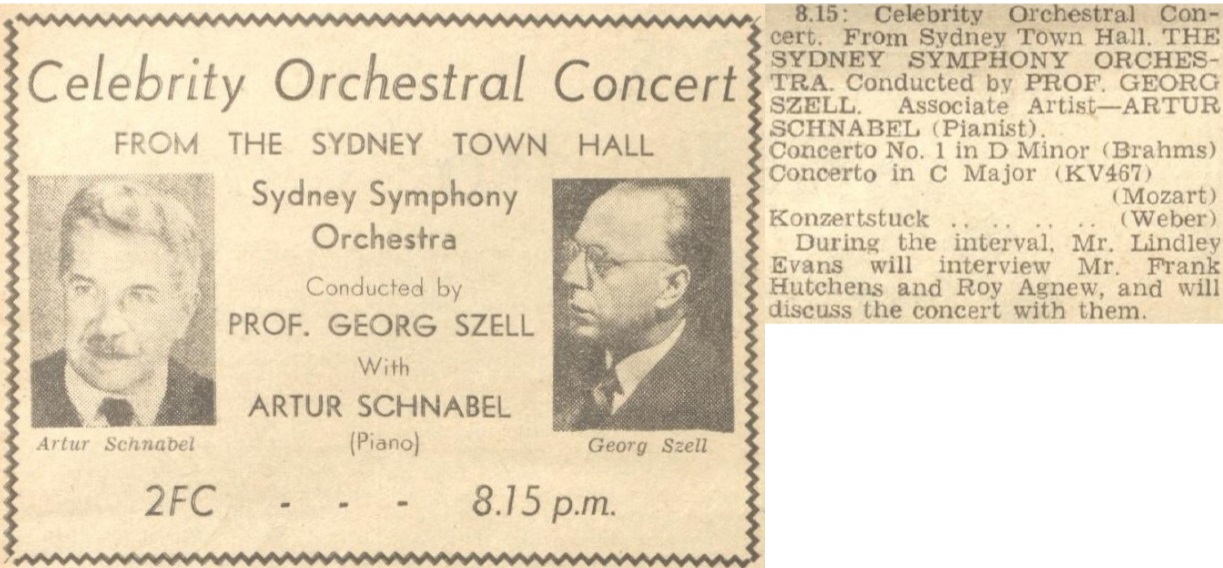

3 Extra Celebrity Concerts:

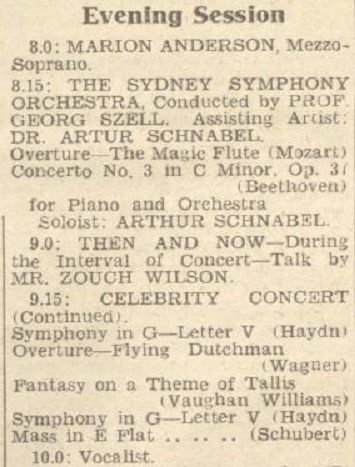

20- July 18 SYDNEY Town Hall

Sydney SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEETHOVEN Concerto n°3 Op.37

Wireless Weekly (July 26): ‘Artur Schnabel’s delicate and expressive rendering of Beethoven’s Third Concerto made the celebrity concert broadcast on Tuesday a memorable one. Simpler and more transparent than the ‘Emperor’, this work showed Schnabel in an entirely favorable light. The Sydney SO, conducted by Georg Szell, provided good support, though on occasions one suspected that Schnabel was applying the spurs. Schnabel completely transformed Beethoven’s C minor concerto by surrounding each change of mood with a delightful sense of intimacy. This seems to bring him closer to his audience than on any other occasion. The last movement – a particularly happy one – was played with more simplicity and restraint than is often heard. Throughout the work, every scale and arpeggio was treated melodically, in this way becoming more closely a part of the whole’.

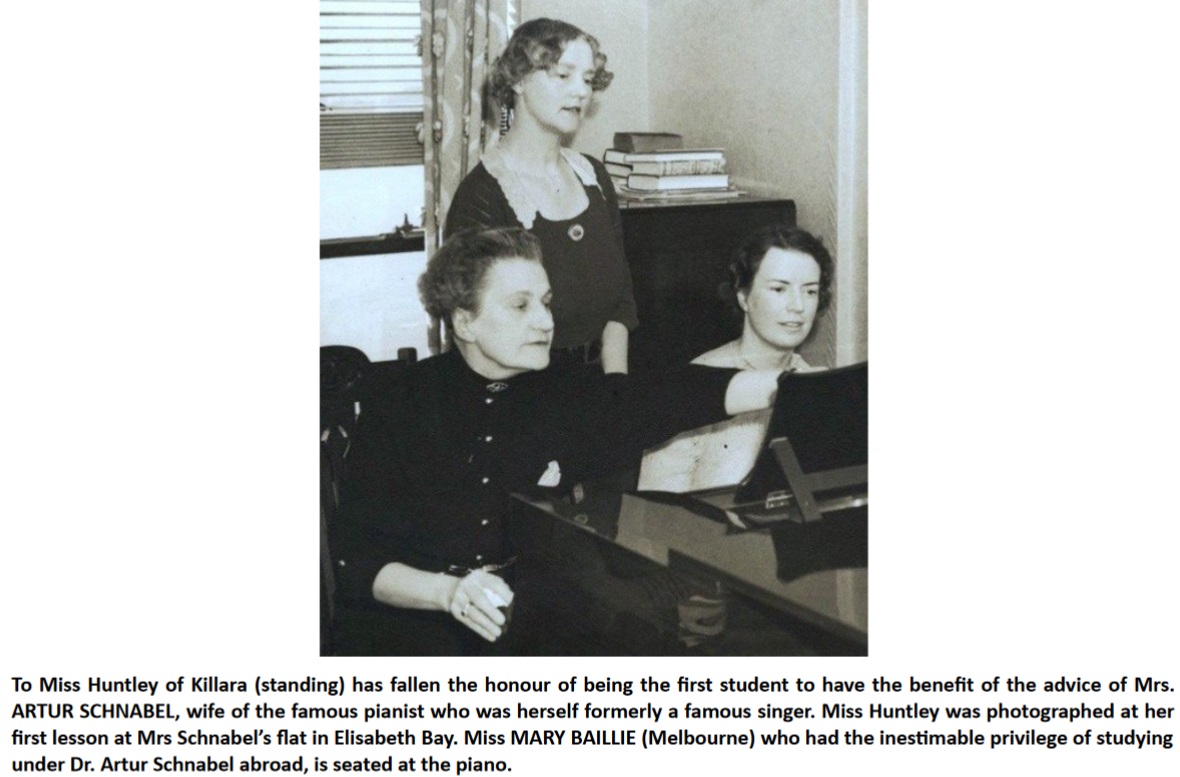

During the tour, Therese Schnabel gave singing lessons to several pupils. The picture below was published in the July 20 issue of the Sydney Morning Herald:

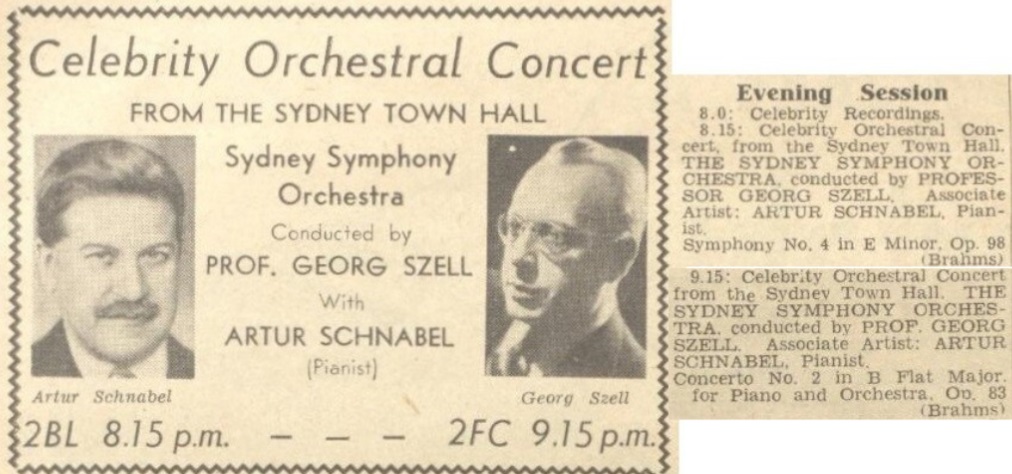

21- July 22 SYDNEY Town Hall

Sydney SO dir: Georg SZELL

BRAHMS Concerto n°1 Op.15

MOZART Concerto n°21 in C K467

WEBER Konzertstück

Sydney Morning Herald (July 24): ‘The complete change of pianistic character between each work and the following one illustrated once more Schnabel’s extraordinary command over style. The Brahms was in the grand manner, painted in with broad exuberant strokes. The Mozart exhaled gaiety, elegance and charm. The slow movement displayed in striking fashion the extreme significance which a highly sensitised intellect and emotional organisation can impart to material of the utmost simplicity. The Rondo was a triumph of nimble, incisive rhythm. The Konzertstuck was one of the most surprising performances that Schnabel has given during his Sydney season. Intrinsically, this music is sweet and spontaneous, but not deep. Like the earlier Verdi, it expresses emotion through lovely melody rather than through form and colour. The march theme which represents the knights returning from the Crusades is almost laughable in the naivety of its scene-painting. Yet Schnabel gave the whole thing such persuasiveness, such sparkllng beauty of ornament, such unspoiled directness and simplicity that it became a rich experience. The showers of decorative passages at the end proved once for all that Schnabel does not disdain a sheer sensuous mode of interpretatlon when it suits his purposes. His earnest approach to the classics is the result of intellectual conviction and not of any lack of temperament. The orchestra gave competent well-judged and sometimes engagingly delicate support to the soloist throughout the concert’.

In a letter to Mary Foreman (Sydney July 25), Schnabel wrote: ‘You will now know that I followed your advice to travel back via the USA, and this knowledge will mean a relief to you,… My work here has swollen to considerable dimensions: 27 appearances, 25 rehearsals, 35 big works, journeys, journalists, auditions, parties, correspondance. And no secretary with me. But, thank God, I don’t feel too tired’.

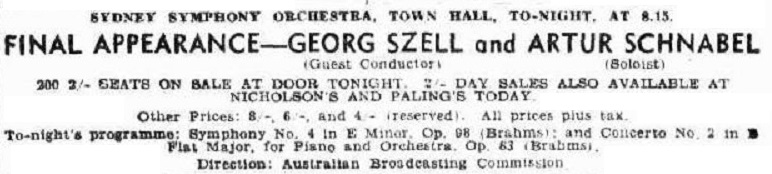

22- July 26 SYDNEY Town Hall

Sydney SO dir: Georg SZELL

BRAHMS Concerto n°2 Op.83

The Bulletin (August 2): ‘The swan-song of a notable musical partnership was sung at Sydney Town Hall on Wednesday night, with a performance of the Second Pianoforte Concerto of Brahms. The orchestra earlier in the evening had given a well-rounded, carefully rehearsed performance of Brahm’s Fourth Symphony, imparting to that work, usually considered so austere, many touches of tenderness and even geniality. The band came to the Concerto, therefore, in appropriate mood, and the result was a supremely satisfying reading of a remarkable work. The illuminative quality of Schnabel’s playing, particularly in declamatory or meditative passages, was never better exemplified’.

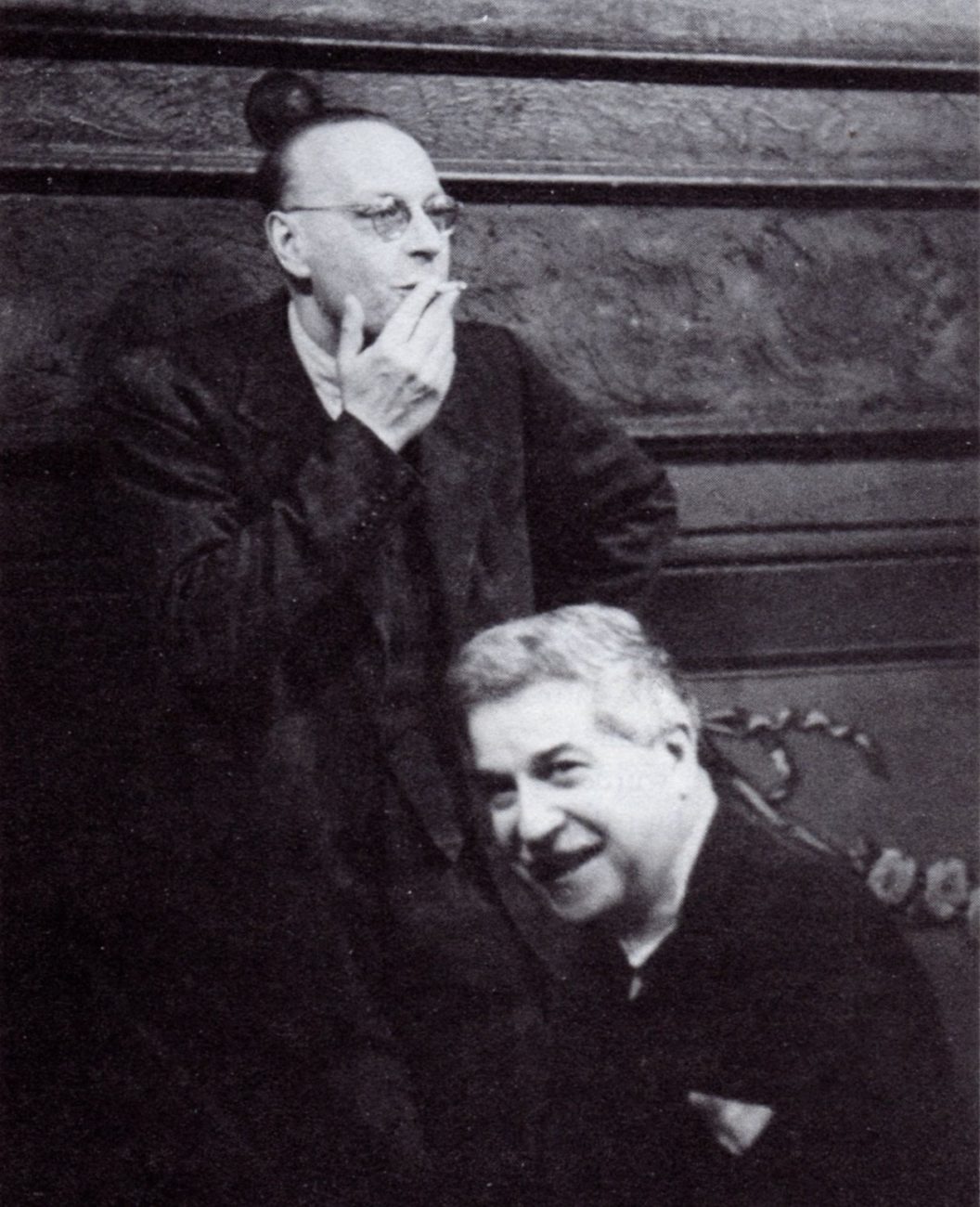

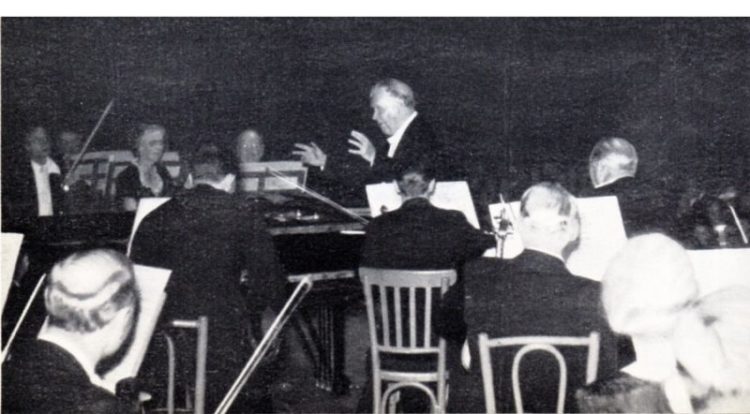

Schnabel & Szell (Australia 1939)

Schnabel & Szell (Australia 1939)

23- July 27 CANBERRA Albert Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 Op.110

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonate n°8 A Minor K310

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 Op.53

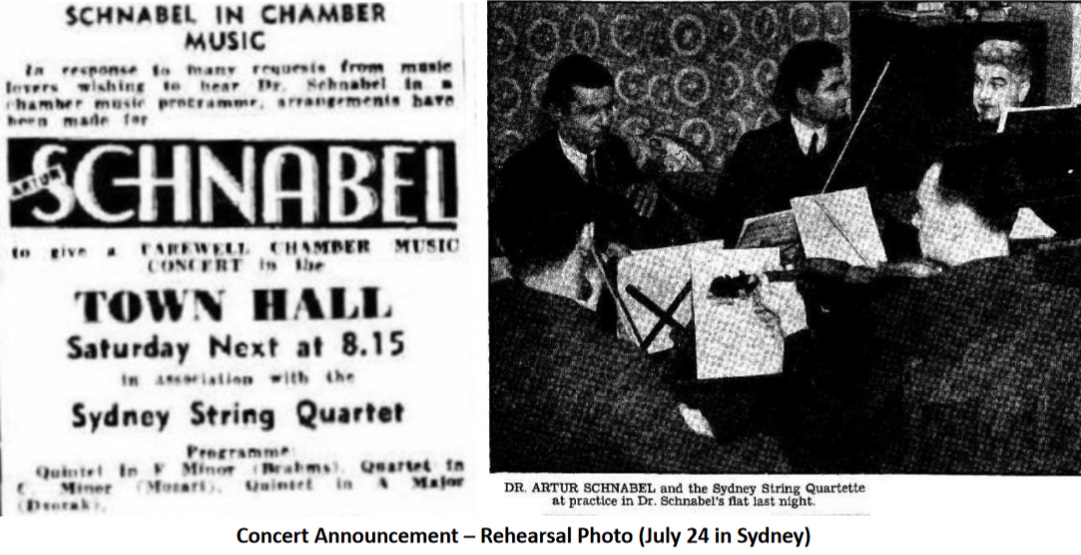

24- July 29 MELBOURNE Town Hall

Sydney Quartet: George White, Robert Miller,Vl William Krasnik vla, Cedric Ashton vlc

BRAHMS Quintet Op.34

MOZART Quartet K 478

DVORAK Quintet Op.81

Age (July 31): ‘The concert given by Artur Schnabel and the Sydney String Quartet in the Town Hall on Saturday night was an event of first importance. George White, Robert Miller, William Krasnik and Cedric Ashton were the string players. Schnabel is a great solo pianist who enjoys taking his part in chamber music. The Sydney Quartet is a capable organisation that has given excellent recitals in Melbourne that are well remembered. Yet, it cannot be said that the ensemble was satisfactory. The strings appeared to lack confidence, but it was soon felt that the hall was too vast for chamber music. While nothing of Schnabel’s playing was lost, sensitive string tone vanished In the great spaces. Interest centered primarily in the works. The Brahms Quintet in F minor, occupied the performers with closely reasoned material. Contrast and variety sustained attention, and while the whole is uniform in excellence, the several movements hold distinctive features opening up new vistas for the intellect and the imagination. Mozart’s Piano Quartet in G minor, with its unclouded idealism, happy contentment and innocent gaiety, expressed with the usual economy of material made everyone good humored. The artists united to declare how inestimable are the treasures that have come from Mozart’s wonder-working brain. Of immense interest was Dvorak’s great Quintet in A. Its originality, wealth of melody, attractive modulation and independent writing bring it close to Schubert’s ideal. In this, the artists were at their best, both in playing and in effect. The vivacious and sympathetic interpretation quite caught the mood and meaning of the much-loved Bohemian master. The performers gained much applause for their recognition of the beauty in these great chamber music works’.

Schnabel’s arrival in Perth from Melbourne (August 6)

A Schnabel interview was published on August 7 in ‘West Australian’. To read it, click HERE

25- August 8 PERTH Capitol Theatre

Perth SO dir: Ernest J. Roberts

BEETHOVEN Concerto n°5 Op.73

In a letter to Mary Foreman (August 9), Schnabel wrote: ‘I had my 25th appearance. Perth is lovely. I am alone here. Perth is quiet, rather elegant, wonderful scenery, fascinating wild flowers, but life is tame. Culturally, comparatively a stepchild. Neglected. The orchestra (amateurs: bakers, shoemakers, street cleaners, etc.) not just a delight for the ear, yet amazing. Something noble and productive might grow even here, the entrance from Europe and Asia to Europe and America’.

West Australian (August 9): ‘We had the power and profundity of Beethoven through the medium of Artur Schnabel’s fingers last night. Making his first appearance in Western Australia, before a large audience in the Capitol Theatre, and under the auspices of the Australian Broadcasting Commission, Schnabel had chosen Beethoven’s Concerto in E flat, Op. 73. After Schnabel’s performance a pianist in the audience, hearing reference to details of the player’s pianism – his wonderfully even, crystalline trills were mentioned – retorted, « Yes, but I forgot all about that. » What was meant, was, more or less, what an English critic meant when he wrote: ‘Schnabel is not just an affair of piano-playing; he transcends the virtuoso’s vain job; he is the living medium of Beethoven’s spirit.’ One agrees heartily. The greater includes the less. Still, let us note that among the gifts which Schnabel places unreservedly and so self-effacingly at the service of the composer is a wide range of tone-power, a command of remarkably vital tone, and of very beautiful soft tones. There were many lovely smooth runs, with beautiful gradations. Perhaps the most beautiful experience the evening held was the opening of the concerto’s second movement, in profoundest peace, muted strings giving out a long, slow music of grave meditation; and then when it dies away, the wonderful effect of the piano’s entry, also meditative, but with another melody, floating down from high in the treble. The very significant orchestral part was managed, under Mr. E.J. Roberts’ direction, with praiseworthy care, and the coordination throughout the performance was good. ‘Fidelio’

26- August 12 PERTH Capitol Theatre Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 Op.110

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonate n°8 A Minor K310

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 Op.53

West Australian (August 14): ‘Wonders, as an acute thinker once remarked, will never cease. Here were we in our thousands, at any rate, as close as makes no difference to the maximum of 2,000 odd which is the capacity of the Capitol Theatre, listening to three piano sonatas (two Beethoven, one Mozart and neither the « Moonlight » nor the « Appassionata » included) and four longish Impromptus (Schubert) which amounted to a fourth. No artist visiting us has been so manifestly distressed by our extraordinary coughing habits as was Dr. Schnabel. His quick glance at us and pained shake of the head when bark broke in on Beethoven were frequent. This apart, it was an evening rich in profoundly impressive experiences. Particularly in Beethoven, the anticipations which the judgment of the musical world, together with our own foretaste in last Tuesday’s concerto had aroused in us were richly realised. To state the conviction which Schnabel’s playing drives, we are taken to the root of the matter. are in touch with, enveloped by, the Beethoven spirit, is to reiterate what has become a commonplace of Schnabel criticism but remains nevertheless the central fact. And, of course, it is more easily asserted than its rightness is demonstrated. There is, indeed, plain for every informed music-lover to see, the integrity of this playing, its fidelity to the text, excluding all ‘effect-making’ for which warrant cannot be found there. Take the first movement of the « Waldstein » sonata. Arrived, after the hurrying, on driving opening page or so at the contrasted, deliberate and expressive second subject, a pianist might be excused for making the most of the contrast with the help of a ritard, and quite a nice effect it would be (and, if memory is not playing one false, often is). But Beethoven has a different purpose, he has not directed any variation of the tempo; so Schnabel resists the temptation and drives the long movement on with unchecked impetus to the momentary slackenings marked by the composer just before its end. The onward driving force of this great piece of music, a purposefulness looking, so to speak, neither to left nor right, was an outstanding feature. Most impressive of all, however, was the profound beauty and significance of changing expression of the Adagio Molto movement, from its hushed opening, with the gentlest of pianissimos, to its passing into the final Rondo; and this passing out of shadows with the serene rondo theme’s first appearance, softly against flowing semiquavers and high in the treble, was a heart-catching, thrilling experience. Such magical moments with Schnabel are all the more potent in their effect because of the absence from his art of sensuousness, and its general masculinity and robustness. Some people, one reads, have not been able to accept the way in which this masculinity and robustness is applied by him to Mozart, who was represented in Saturday’s programme by a very fine sonata in A minor (K310), a work full of impassioned feeling and by no means music of « lavender and old lace » (to quote the sarcastic phrase with which the programme-annotator hit off a conventional view). From the lavender and-old-lace way of playing Mozart that of Schnabel is certainly separated by a considerable distance. How far in the Schnabel direction it is desirable to go may be granted to be a debatable point. Dogmatism on it would be rash, and it will not be attempted here. (One may add, though, that at least one of Schnabel’s passages in this sonata was given a tonal and textural exquisiteness which must have ravished even old-lace addicts). The recital opened with the last but one of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, Op.110, in A flat, its performance adding one more to the collection of Schnabel records: it had not been played before in Perth, so far as we can recall, by any visiting celebrity. Beethoven was 51 when he composed it (in 1821) and had six more years to live. We must be grateful to Dr.Schnabel for letting us hear this noble and beautiful work, not less than for his masterly presentation of it. The strength and commanding asssurance in the final fugue were inspiring. Before the interval we had four Impromptus by Schubert (Op. 142). The First, in F minor, is virtually a sonata first-movement, a finely inspired piece, full of Schubertian warmth and vigour of imagination; the second is the well known Allegretto movement in A flat major, the third a beautiful series of variations on a theme from the « Rosamunde » music, and the fourth a lively, brilliant finale, somewhat in the Hungarian manner. Is it ungracious to mention the solitary qualification to one’s joyful appreciation of all this: the feeling of excess of repetitiveness by Schubert in the famous A flat piece, when all his repeat marks are observed, as they faithfully were by Dr. Schnabel?’ ‘Fidelio’

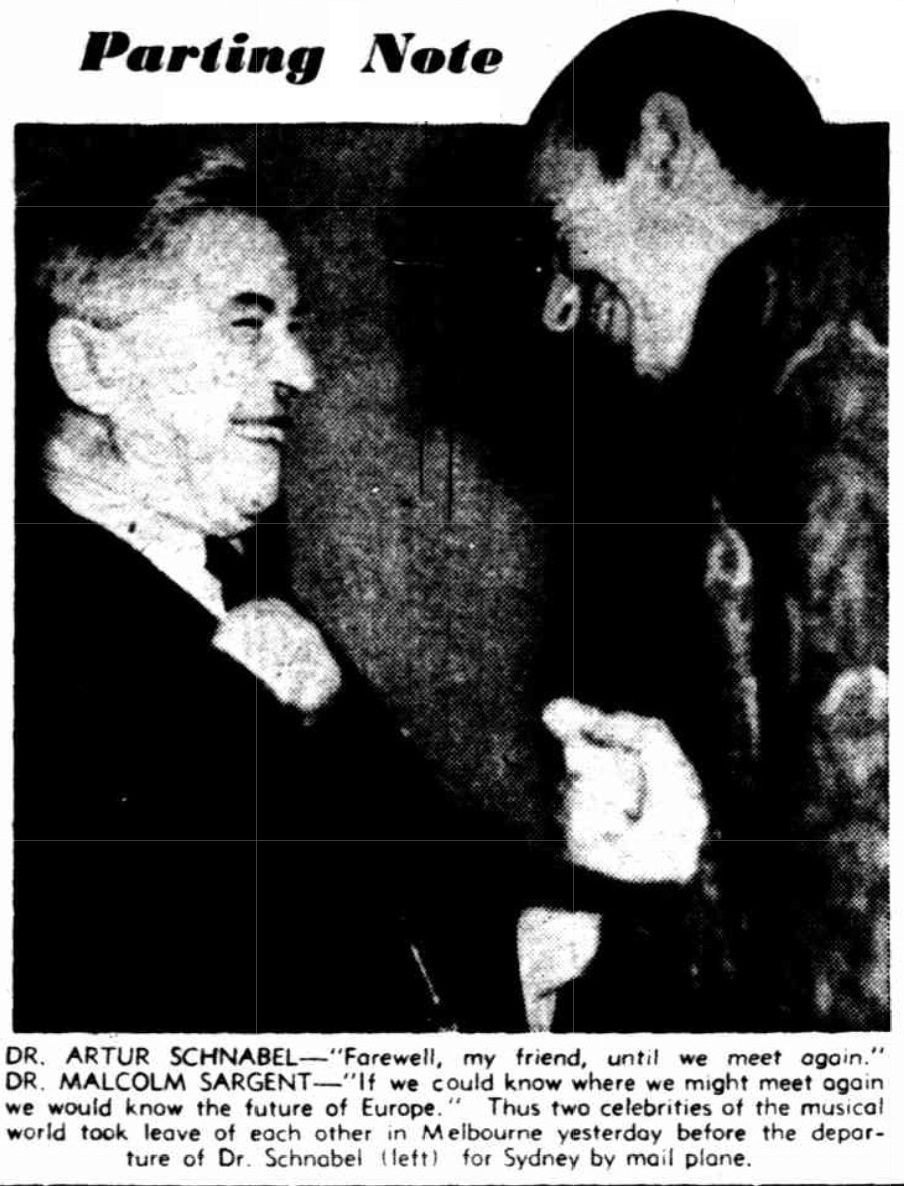

Schnabel’s meeting with Malcolm Sargent at Melbourne airport (August 14)

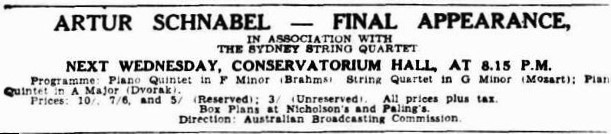

27-August 16 SYDNEY Conservatorium of Music

Sydney Quartet: George White, Robert Miller,Vl William Krasnik vla, Cedric Ashton vlc

MOZART Quartet K 478

DVORAK Quintet Op.81

BRAHMS Quintet Op.34

The Bulletin (August 23): ‘Quite the best of the many concerts and recitals in which Artur Schnabel has taken part in Sydney was the performance of pianoforte and strings at rhe ‘Con. Hall’ last Wednesday night which brought his Australian season to a close. The Sydney String Quartet collaborated with the Viennese musician in the Brahms F Minor Quintet , and the result was admirable. For once in a way the reserved and imperturbable Schnabel seemed to glory in the music, and the other instrumentalists played as they have never played before. Mozart’s G Minor Quartet (K478), which ranks with the symphonies in merit, was given the sort of performance its elegance and suave beauty demand. Schnabel is the ideal Mozart-player (he can make even a simple Alberti bass sound distinctive), and his manner, as in the Brahms, infected his associates, so that each voice had its say in exactly the right accents. Dvorak’s sensuously melodic Quintet in A (Op.81) brought a notable evening to a close. The attendance, though it crowded the ‘Con. Hall’, whose normal seating arrangements were extended, was not nearly of Town Hall dimensions, but it was quite obviously an intensely musical audience, and its sympathy and appreciation had their effect upon the performers.

On August 18, Schnabel left Australia with the SS Monterey from Sydney to Los Angeles. This was reported in the ‘Daily Telegraph’ the next day.

From his biographer, César Saerchinger, we know what this meant: ‘They had lost their German home, then their Austrian nationality; they were now forced to abandon their second home in Italy – for an indefinite time. And willy-nilly, they were now in their future adopted country, the United States. The war not only meant banisment fom one continent to another, but also a radical change in a long-established pattern of life. Schnabel was born an Austrian, had lived and thought as a German and a European in the fullest sense of the word…. Now, for the first time, he was obliged to remain stationary in the New World, and this at a time when his personal honeymoon with America was over, after the first impact of its conquest had been spent. ‘We are marooned’, he wrote to Walter Turner from New York. ‘Grateful as I am to be here, I am not happy… I feel great apprehension for the U.S.A., which in a sense I seem to love more and appreciate more highly than the majority of the people who «keep smiling»’. The basis of his apprehension was the deterioration of society under the pressure of materialism, and its exploitation as an ever-expanding market for mass-producted articles: ‘For music, there is no understanding of the prerequisites of its appreciation. Its mystical origin and its transcendental essence is not admitted… Obviously, there is no place for me here’.

From then on, he lived in the United States, until he was to see Europe again, but for this he had to wait until in May 1946. There, he resumed his musical activity with a series of concerts and recordings in London.

Artur SCHNABEL – AUSTRALIAN TOUR 1939 PART I: Concerts n° 1 -11 (May 17 – June 13)

MELBOURNE, HOBART, SYDNEY, BRISBANE

Introduction: Der schwer gefaßte Entschluß… (The difficult decision)

Eighty-five years ago, Artur Schnabel toured Australia for three months (May 17 – August 16, 1939). His intention was to come back to Europe at the end of the tour, but it became more and more obvious in the course of time that Word War II was about to break out. Meanwhile, the tour went well and seemed undisturbed by the gruelling and heart-breaking decision he had to develop over time to leave all his belongings in Europe and go to the United States.

_________________________________

Between January 25 and 27, 1939, Schnabel made in London (Abbey Road Studio n°3) what were to be his last pre-war recordings. Thereafter, he travelled to the United States to give some concerts: Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Chicago, San Francisco and finally Los Angeles, from where, on April 26, he took SS Mariposa to travel to Sydney where he arrived on May 15. The first concerts were in Melbourne and Hobart (Tasmania).

During this tour, Schnabel performed 5 different programs for his 16 piano recitals. There were also 2 chamber music concerts and 9 orchestral concerts, six of them being conducted by Georg Szell.

From Australia, he wrote letters to his friend Mary Foreman. They have been published in: ‘Artur Schnabel – Walking Freely on Firm Ground – Letters to Mary Virginia Foreman 1935 – 1951’ (Wolke Verlag). From them, we know the reasons why Schnabel took the very difficult decision of not going back to Europe and, at the end of the tour, of sailing to the United States.

01- May 17 MELBOURNE Town Hall

Melbourne SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEEETHOVEN Concerto n° 4 in G Op.58

Announcement of the broadcast of the Concerto by Beethoven

and below, rehearsal with Schnabel and Szell with the Melbourne SO

Argus (May 18): ‘A musical event of great importance, the first public appearance in Australia of Artur Schnabel, resulted in scenes of indescribable enthusiasm last night at the Town Hall. Music lovers rejoiced that for his opening concert in Australia, he paid the Melbourne Symphony players the supreme compliment of soliciting Beethoven’s G major concerto, a work which reveals his genius and his scholarship at their highest level of achievement. Professor Szell’s association with the great pianist gave further cause for congratulation. These two musicians have been partners in many a fine artistic enterprise, and each nuance and each hint of emotional significance in the Schnabel’s reading of the G major concerto is as familiar to the conductor. as to the soloist. There are some musical interpretations which defy analysis and remain in the memory as intangible but indestructible revelations of beauty. Of this rare calibre was the performance heard last night. No written summary could convey the poetry, the authority, the grandeur, and the impulsive youthfulness of an interpretation which, premeditated as to each detail of colour and form, avoided any suspicion of intellectual routine. Schnabel’s encyclopaedic knowledge of Beethoven’s compositions might easily tempt him to pedantic dryness. So alert and so eager are his mental reactions, however, that his renderings have the unspoilt freshness of improvisation. Although the Melbourne orchestra could not supply the beauty of tone necessary in the first movement of the concerto, the vivacity of rhythm in the finale and the admirable sense of mood achieved in the « andante » caused equal pride and satisfaction to all admirers of Australian talents’. Bicknell Allen

The Bulletin – Melbourne Chatter (May 24): ‘As their husbands are old friends, so are Madame Schnabel and Madame Szell, who where at the first row of the gallery with a bunch of A.B.C. (Australian Broadcasting Commission) people.

The Bulletin (May 24): ‘…The audience cheered, clapped and stamped when Schnabel played the G Major Concerto of Beethoven. Schnabel is one of the rare creatures who not only knows how to play their instruments, but how to play their audiences’.

02- May 20 HOBART Town Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Mercury – Hobart: ‘Those who had the good fortune to be at Artur Schnabel’s recital at the Hobart Town Hall on Saturday night heard Beethoven played as they are not likely to hear lt for many years unless they hear Schnabel again. One can well believe, after having listened to his intensely authoritative readings of the A Flat and C Major sonatas that no other artist living can compare with Schnabel in his vast understanding of the piano works of the great composer. It was tremendous playing, and at the end, the large audience, which overflowed beyond the usual space of the hall – even onto the platform – broke into a storm of applause; a Schnabel audience, one imagines, is always enthusiastic. The pianist returned time after time to bow his acknowledgements, but there were no additions to the programme, for Schnabel does not give encores. « Applause, » he believes »is not an order, but a receipt. »…Schnabel’s absolute sincerity and rare penetration into the composer’s mind left, perhaps, the deepest impression. He never failed to get below the surface of the music and illuminate its essential characteristics. He absorbed himself and his art completely in his playing. The glorious A Flat Sonata, Op. 110, the second last which Beethoven wrote for the piano,,was a memorable experience. lt was a fluent exposition which left unexpressed none of the moving beauty and spirit of the music. Schnabel’s cantabile was delightful alike at the outset and in the statement of the fugue subjects. Clarity of tone, pursued so ardently, attained so rarely, was one of the secrets of this great performance. In Beethoven’s monumental « Waldstein » Sonata (C Major, Op.53) Schnabel, especially in the allegro con brio, rose to exceptional heights. His playing was unforgettable alike for meticulous and exquisite turn of phrase and for solidity and forthrightness. Great skill and expression were lavished on the allegretto. That Schnabel is not a Beethoven exponent alone was shown by his masterful interpretations of the Mozart A Minor Sonata and the four « Impromptus » which constitute Schubert’s Opus 142. The A Minor, typical of the emotional Mozart, alternately glowed and trembled with passionate beauty. The piano gave out a wealth of glorious tone, soaring at times to stirring climaxes, which, no matter how forceful, were always perfectly controlled. For me, the first and second of the « Impromptus » were the loveliest. Schubert’s enchanting’ melodies were articulated with complete lucidity, and the last two pieces were revelations of virtuosity. A Steinway plano was used hy Artur Schnabel at his recital. ’Themus’

03- May 25 MELBOURNE Town Hall

Melbourne SO dir: Georg SZELL

BEETHOVEN Concerto n°1 in C Op.15 – MOZART Concerto n°20 D Minor K466 – SCHUMANN Concerto in A Op.54

Australasian (June 3): ‘No more important musical event is likely to occur in Melbourne this year than the all-concerto concert given at the Town Hall on May 25 by Artur Schnabel and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. A profound musical scholar and the greatest contemporary exponent of Beethoven, Schnabel makes life difficult for orchestral associates unfamiliar with his analytical methods. The Melbourne Symphony players struggled pluckily to fulfil the insistent demands upon their technique and initiative, demands which were no more than commonplaces of interpretative routine to conductor and soloist, but which weighed heavily upon performers already sufficiently alarmed by Schnabel’s reputation and uncompromising devotion to « high-brow » principles. Artistic collaboration was out of the question, but, with the pianist as dictator and the conductor as a quick-witted and efficient intermediary, the orchestra provided an effective background for the magnificently handled solo passages. Beethoven, Mozart, and Schumann were the composers of Schnabel’s choice, and to each he devoted his great learning, his exemplary musicianship, and his consummate control of piano technique. As at the previous celebrity concert, when Schnabel gave an inspired performance of the Beethoven G major concerto, the Town Hall was « sold out » several hours before the programme commenced, and voices, feet, and hands swelled the torrents of applause. To watch the face of Artur Schnabel when he plays the andante section of the G major concerto would bring a deaf man into spiritual communion with the music’. ‘Musician’

The Herald (May 26): ‘Schnabel’s masterly playing of the Schumann A Minor concerto made an exhilarating climax to the concert in which the eminent pianist was associated with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, under Professor Georg Szell’s direction, in the Town Hall last night. Breadth and strength characterised the playing of the artist, who, in the performance of three concertos, again impressed as both a great pianist and a profound musical scholar. Never did Schnabel’s playing flag and never was there anything superficial in the playing. His interpretations were intensely alive, piercing to the core of the music. While he gave luminous readings of the Beethoven No. 1 and Mozart’s D Minor (K466), the peak of achievement was reached in the Schumann, because the pianist had better support from the orchestra, which was responsive to every mood of Schumann. The orchestral background seemed to be revitalised on this occasion. Although strong and exhilarating, the performance did not lack tenderness. It was at once distinguished by the vitality, clarity, and romantic spirit with which soloist and orchestra developed the web of harmonies of the first movement, In the Intermezzo the audience was enchanted with the gracious charm of the interchange of themes between the piano and strings, and later the woodwind. Sensitive cello tone came in the sustained melody against the arpeggio passages of the piano. A magical effect was achieved just before pianist and orchestra entered into the brilliant and joyous Allegro Vivace. Schnabel and the orchestra revelled in the animated first part of this movement, with the arabesques of the piano dancing round the sprightly melody voiced by various parts of the orchestra in turn. The pianist made a sterling impression by his brilliancy as he proceeded from one tour de force to another to the exciting close. The drama of Mozart’s D Minor concerto made a deep impression. In the first movement there was a cadenza of arresting interest. This was a real dramatic summing-up, that tightened not loosened, the interest. The concert was begun with the Beethoven work, which was most notable for the spontaneity of the Rondo. Schnabel had better support later in the night than he received in the earlier movements. J. E. Tremearne

On May 26, Artur Schnabel and his wife Therese Behr flew to Sydney. Schnabel was to give four recitals in a row. The picture below shows them at their arrival in Sydney.

Announcement for the Sydney Recitals

04- May 27 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 1

Original Program [BEETHOVEN Sonatas n°2 Op.2 n°2; n°31 Op.110; n°17 Op.31 n°2; n°21 Op.53]

Announcement (May 15) for the May 27 Recital

The amended program, no longer with only Beethoven Sonatas, was announced in the press on May 20, the day of the Hobart Recital where the same program (‘Program 1’) was played:

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Daily Telegraph (May 29): ‘Artur Schnabel, opened his Sydney season with an electrifying concert at the Town Hall on Saturday night. Schnabel, a small man, discarded the usual pianist’s stool for a high-backed chair, against which, in slow movements, he would lean back listening intently to the lovely sounds he, produced. He demanded the undivided attention of the large audience. Schnabel’s reading of Beethoven’s Sonata in A Flat Major Opus 110, was so fresh and spontaneous that the work, heard dozens of times before, seemed to have been written only last week. Unbelievably delicate gradations of tone and color added detailed loveliness to the great architectural interpretation. There was no exaggeration; each note received just the right value to balance it with the rest of the work. Technical difficulties seemed not to exist. Yet there was nothing of the self-advertising virtuoso about the performance. One felt that the credit was due primarily to the composer, rather than to the player. This was no so with Schubert’s Four Impromptus. In this group one felt « Here is great playing, » not « Here is great music. » And it was only the combination of Schnabel’s immense personality and faultless playing that sustained the interest throughout the over-long work. The first movement of Mozart’s A Minor Sonata (K.310) lacked the delicately smooth yet firm articulation which characterises ideal performances of that master’s work. But Schnabel played the rest of the sonata with transcendent beauty of phrasing and tone. He concluded his generously long programme with a monumental performance of Beethoven’s « Waldstein » Sonata, which left the audience in a state of high elation. To call Schnabel’s performance of this work « poetic » would be to use a word staled by hackneyed use to describe a thing of new-born freshness. Yet poetry, true poetry, was in every note. An unforgettable and beautiful experience’.

Sun (May 29): ‘There is some piano playing so superb that one can only lose oneself in admiration for it. The combination of intellectual and emotional understanding of music, and of transcendent technique is so rare that such an experience is not often enjoyed in the concert hall. Artur Schnabel, however, gave lovers of music this supreme gift at his first recital in Sydney Town Hall on Saturday night. We have heard some technicians as fine, and a few pianists who were able to reach beyond the technical mastery, and the mechanism of strings and keys to the spirit of the music behind and above these things,but it is difficult to remember a player who can satisfy as Schnabel can. His most obvious quality is that of reserve. He greets his audience quietly, and then, sitting at the piano, promptly forgets it – except when some loud cough breaks in upon him, when he frowns and shakes his head as he seeks to recapture his mood. He has no distracting mannerisms. He opened his concert with the Sonata Opus 110, a late work of Beethoven not often heard on the concert platform, and containing much of that metaphysic which makes the later Beethoven so difficult to interpret. No such interpretation as Schnabel’s has been heard in Sydney. He resolves the difficulties of phrasing and of thought as if Beethoven himself were speaking, still retaining that sense of the mystic, which is the ultimate wonder of all great music. The « Waldstein » Sonata is usually regarded as a virtuoso piece, something written for technicians, and we have heard many performances which give color to that idea. The « Waldstein » Sonata, as it was done by this fine musician, was an utterance of music just as moving and as beautiful as any piano work ever written by the Master. The Mozart Sonata in A Minor has been done by almost every advanced piano student, and never by a professional pianist from abroad until it was done at this concert. The pianist brought out into relief the escape from formalism of the growing musical individuality of Mozart. Mozart is so often played four-square with an attempt to give meaning to him by a certain fragility. As Schnabel sees him, he is a man’s composer, with a virile musical message. The four Impromptus of Schubert were played together, as impressive as a sonata in a sort of contrasting unity of sense, if not of form. Listening to this great pianist and musician, one wondered why other virtuosi have not sought further into the essential Schubert. The reaction of all this beautiful music on the audience was obviously great. With the exception of one or two stentorian coughs, even those with irritable throats bottled up their coughing to let it go between sonata movements. During the actual playing not a sound was heard from that crowded house. The applause was continuous. The pianist was recalled again and again, though it was known that he would play no encores. He says that he has found Australian audiences understanding and sensitive, and Saturday night’s audience plainly manifested these qualities’. H.A.

Publicity for Bechstein Pianos (May 28)

In Hobart however (May 20), he played on a Steinway piano, but for the whole Tour, Bechstein was of course the instrument of his choice.

05- May 30 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Sydney Morning Herald (May 31): ‘Artur Schnabel once again made a profound impression last night when he gave his second recital at the Town Hall. The cordiality of the applause at the end indicated how deeply the audience had been stirred even though there was no attempt to transgress the pianist’s wishes and demand encores. The Schubert sonata was especiallv interesting, for the new light it threw on this composer. Until recently Schubert’s accomplishments in sonata form where overshadowed by his fame as a svmphonist and a song writer, and by the popularity of the Impromptus. But abroad during the past few years, Schubert’s sonatas have been reinstated as first class music. And Schnabel himself has been a leader in that movement. The B Flat Sonata was remarkable for its extreme lyric beauty and for its graceful simplicity of form. It glowed and beamed under the pianist’s melodic eloquence. Everything seemed easily done, yet the details had that exquisite proportion which only the greatest concentration could bring to pass. The climaxes grew so surely and so spontaneously that they seemed an organic development rather than a series of consciously thoughtout effects. A similar selfless devotion to the musical thought appeared in the C Minor Beethoven. Schnabel last night gave it a new intensity, a new sparkle, an entirely unexpected set of values It was all done by simplification and not by the imposition of an arresting and picturesque personality. Therefore, it seemed irresistible and noble. The Mozart also was playing of a richly aristocratic quality. It had strength and resonance yet every phrase had been polished to the last degree. The crown of the evening’s music, however, was the Beethoven Opus 109. To this strange and powerful product of the composer’s later years, Schnabel brought a corresponding maturity. The great range of the tonal effects , the clouded qualitv of the song, the abrupt shifting of mood, the brooding and the interludes of radiant calm – all these found expression on the grandest scale’.

Sun (May 31): ‘Schnabel’s selection from Schubert was the Sonata in B Flat, a long work with a very diffuse first movement, which, had it not been for Schnabel’s rare gift of making poetry out of blemishes, might have proved dull. The second and third movements were pure Schubert, down to the finest detail. One feature of Schnabel’s technique which deserves particular attention is the sonority of his bass, the harmonies of which, in some of the Beethoven movements, assume a truly symphonic volume. The prestissimo section and the more richly harmonised portions of the final variations in the great Beethoven work In E Major Op.109 were handled by this pianist with studied attention to harmonic embroidery. Schnabel’s choice from the Mozart album was an exquisite and melodious Sonata in F Major, practically unknown to concertgoers here. Instead of the broad, powerful imaginative flourishes given to his Mozart playing on Saturday night, the treatment was more delicate. The audience greeted an old friend in Beethoven’s Pathetique Sonata, which was done with verve and breadth of conception. Repeated calls for an encore at the conclusion of the concert were met with polite bows from Schnabel, but there was no more music’.

06- June 1 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 3

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°3 in C Op.2 n°3 – Sonata n° 17 in D minor Op.31 n°2

SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.90 D899 – SCHUBERT Sonata n°17 D Major Op.53 D850

Daily Telegraph (June 2): ‘His first offering was Op.2 n°3 in C Major, » a work known to every young piano student. In this, which he started rather restlessly, Schnabel used more pedal than usual – much more, in fact, that he advocates in his own edition of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. His slow movement, especially the bit with crossed hands, was a marvel of lyrical beauty. The fortissimo passages, when they came, made a tremendous effect. There was no attempt to make the minuet dainty. It just bubbled with masculine good humor. Even In the most delicate passages of the last movement, Schnabel never for a moment lost his intense virility. The other Beethoven work was the Sonata in D. Op. 31, No. 2. Schnabel illuminated this work, too, with that insight into its essential meaning, through which he makes the most complex music seem easy to his audience. His was the only way to play the work. You knew that at once, despite an occasional blurred articulation. Schubert’s Four Impromptus, Op.90 and Sonata in D Major, Op. 53, took up the rest of the programme. Beautifully though they were played, Schubert makes a poor show after Beethoven’. J.R.

Sun (June 2): ‘Of the works on the program, the Beethoven in D Minor was naturally the most impressive. The pianist found here material for one of those splendid interpretations which distinguish him, its strongly organised structure and dramatic power being realised magnificently. Particularly beautiful was the treatment of the slow movement, in which the handling of the chords, so accurately and yet so gently played, was a notable feature. In his chord playing, one always notes with Schnabel an extraordinary dynamic control, resulting in the most lovely shading of such passages,and a significance in phrasing which lesser players miss. It is more than technique – any good technician could do it – but few of them have the instinct to do it. Such passages, for instance, as the opening of the slow movement in the C Major, revealed on examination some very subtle differences in volume and color of a series of chords which seemed, on considering the whole, evenly played. These variations gave life to the phrases which a less subtle treatment denies them. Schnabel, with all his technical accomplishment, is not superior in this respect, to many other pianists we have heard. Listening to the D Minor Beethoven last night, however, it was possible to see that the secret of his pre-eminence in interpretation of the classics is an almost unique capacity to see a movement as an organic whole, and to keep it always within the frame. An approach reserved, and at the same time warm, enables him to give the full poetic significance to these works, which are, after all, poems in sound. Again he demonstrated his power of holding his audience, not by platform tricks, not by any attempt at ingratiation, but by the sheer force and understanding of the music he plays, an understanding which he communicates to those who hear him. Even the Schubert Sonata, inorganic as it was, lacking development,and relying superficially on its melodic interest, he invested with a certain glow, for the time making one feel that, instead of a good work, it was a great one. That capacity to give quality to a work which somewhat lacks it, is the finest and rarest mark of a great player’. H.A.

07- June 3 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 4

BACH Toccata C Minor BWV 911 & D Major BWV 912 – SCHUBERT Moments Musicaux Op.94 D780

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°25 Op.79 – Sonata n°24 Op.78 – Sonata n°32 Op.111

Sydney Morning Herald (June 5): ‘One could have foretold from knowledge of his earlier performances, what style the pianist would bring to Bach’s music. Yet, the reality, when it came, was surprising in the degree of its breadth and penetration. This was Bach reduced to the simplest terms, square and powerful, yet not in the slightest dessicated. During his four Sydney concerts, Schnabel presented Beethoven on a new scale, with a new set of values. When displayed by the majority of pianists, a Sonata like the G Major Op.79 sounds a trifle thin and dated. One has been aware, at times,that this sonata fails to equate others and later works in the exploitation of technical possibilities,and of the full sonority of the keyboard. Yet, with Schnabel as interpreter, nothing of that impression remained. The three movements sang fully and completely, and the music was re-established. The G Major sonata was followed by the one in F sharp Op.78. This was irresistible in its suave grace. Finally, Schnabel played the towering Op.111. In sheer sultry majesty and introspective passion, the first movement stood supreme. The stormy, rumbling declamation of the bass was uncompromising, abrupt, minatory. It had an elemental roll, a colossal sweep of colour. The remaining work was the Op.94 of Schubert. Even Saturday night’s playing, exalted as it was, could not give these miniatures any particular importance. That was probably not the player’s aim. What he did do was to point out Schubert’s lucidity and fragikity and perfect taste when it came to a series of charming trifles’.

Daily Telegraph (June 5): ‘The Town Hall was filled on Saturday night for the last concert of Artur Schnabel’s present season. Once again he demonstrated his complete mastery of Beethoven’s works. The performance of the evening was the Sonata in C Minor, Op.111. He handled this monstrously difficult work without apparent effort. Under his fingers, the lovely Arietta sang its way upwards until it dissolved into the most ethereal sounds I have ever heard come from a pianoforte. Fortunately the Op.111 was the last item on the programme. It would have been impossible to listen to anything else. But Schnabel had already given inspired performances of the slight Op.79 and the more profound Op.78. There was no nonsense about Schnabel’s playing of the two Bach Toccatas in C Minor and D Minor, with which he opened the concert. The several parts in the complicated polyphonic writing could all be heard with beautiful clarity. Once again Schubert figured prominently on the programme, this time with the Six Moments Musicaux. Schnabel lent these more or less trivial pieces a vicarious dignity. But many of them, particularly the Andantino, are too long. If they represented what Schubert took to be a « moment, » he must have suffered from some strange aberration of the time sense’ J.R.

The Bulletin – Melbourne Chatter (June 7): ‘On Saturday night, he had an inauspicious beginning. His first item was a Bach toccata. He was just getting into its stride when there came a fizz and a flash as of lightning. A photographer leaning over the balcony had done the fell deed. Schnabel, rudely awakened, played on for a few bars, then stopped abruptly, muttered several fierce denunciations in a foreign langage, and when a little calmer, started all over again.’

08- June 6 BRISBANE City Hall

Brisbane SO dir: Percy CODE

MOZART Concerto n¨23 A Major K488

On June 6, the Brisbane newspaper Telegraph published an article ‘Walking and Talking with Schnabel’, which relates the conversation between the pianist and the newspaper’s music critc walking together from Schnabel’s hotel to the rehearsal room for the 11 a.m. rehearsal at City Hall with the orchestra. To read the article, click HERE

Telegraph (June 7): ‘Artur Schnabel amazed his audience at the City Hail last night by his own unobtrusiveness. He played the solo part in Mozart’s A Major Concerto as if he were the least important of all the musicians on the platform. He sat at the piano and played as if he were merely gratifying a whim of a few friends at his own fireside, often keeping both eyes on the conductor and none on the keyboard. Twice in the last movement, his hands actually rose higher than the top of the grand piano, and there was not a movement of any kind in his bodily position. He gave us the best Mozart playing we have ever had. His clear rippling tone was admirably balanced with the orchestra, every tiny figure of ornamentation which Mozart wrote was there in its proper place, beautifully clear. He seemed to have unlimited reserves of power. In the slow movement, his tone was gloriously pure. I do not think we have ever had a concerto performance in which there has been the same degree of close collaboration between soloist and orchestra. Mr. Percy Code managed the orchestra very successfully, holding it down to just the right strength of tone on nearly every occasion, and it was not his fault that here and there tiny blemishes appeared in the wood-wind performance’. A.H.T.

09- June 8 BRISBANE City Hall Program 1

BEETHOVEN Sonata n°31 in A Flat Op.110 – SCHUBERT 4 Impromptus Op.142 D935

MOZART Sonata n°8 in A Minor K310 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°21 in C Op.53

Telegraph (June 9): ‘The unobtrusiveness that was noted in the earlier Mozart concerto performance was not abandoned. Schnabel allows nothing to come between him and the music. One soon took his technical powers for granted. For no technical hurdles seemed to matter. The intense spirituality of the sonata Op.110 seemed to grip him as it did every member of the audience. The marvel is how he achieves such variety in tone colour, and in the actual weight of tone, without obvious effort. His fortes rise like an incense from the keyboard. Every phrase and every nuance is so carefully conceived and executed, and yet seems to be so part and parcel of the man himself, that it completely disarms criticism. There is no fuss or bother even about his big tone, which seems to come unbidden, from a slightly raised elbow and wrist. For sheer control of tone the series of chords rising from pianissimo to fortissimo in the last movement of the Op.110 were perhaps the most surprising. He made every one of those chords a very great surprise, and one began to wonder how much longer he could have gone on increasing the strength. The crystal purity of his tone made it carry to every part of the hall and he seemed to annihilate distance with it, his softest pianissimo being as audible from the gallery as his loudest tones. It was an unforgettable experience. The four Schubert Impromptus Op.142 were so perfectly matched as to almost form a sonata, though rather a long one. Schnabel believes that Schubert is a much underrated pianoforte composer to-day. He proved it in this performance, which had all the clarity, all the melodic richness of content, and all the fire one could wish for. Professor Donald Tovey has remarked that it was time we ceased regarding Mozart as a namby-pamby, and « lavender and old lace » composer and gave him something of the bigness that is his due. That is precisely what the pianist did last nightwith his A Minor Sonata K310. Its dynamics were, in Mr, Schnabel’s hands, very much the same as the Schubert and the Beethoven. The Beethoven « Waldstein » sonata has never been heard here before as it was heard last night. The performance was magnificent. Great as the playing had been earlier, I do not think there was anything quite like the marvellous variety in colouring that he gave the last movement, nor anything to match the crystal purity of his tone in the slow movement. It was sheer keyboard wizardry with the wizard performing with the nonchalance of a conjuror producing rabbits from a hat’.

10- June 10 BRISBANE City Hall Program 2

SCHUBERT Sonata n°21 B Flat D960 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°8 in C minor Op.13

MOZART Sonata n°12 in F K.332 – BEETHOVEN Sonata n°30 in E Op.109

Telegraph (June 12): ‘Rarely or never have we been visited by a player who could take so much for granted on the merely technical side and who was in consequence so free as he to devote himself to what one cannot but call the spiritual content of the music. Lesser men watch their keyboard as though it otherwise might play them some trick. He had other things to watch. The result was, for example, a new and utterly transformed « Pathetique », that Beethoven Sonata heard so often as to provide the test almost of the hackneyed, and a Mozart which in hands less great would sink to tinkling prettiness, but which in his was a thing of unblemished grace and graciousness. One might discourse on the detail of this perfectly architectured programme, on the glorious statement of the recurring theme in the first movement of the Schubert Sonata, on the etched rhythm of its Scherzo, on the dynamics of the first movement of the final Beethoven and so on, were it not an impertinence to do so. There must have been many in that audience who, like the writer, had heard recorded versions of Schnabel’s work years ago, and said: « This is the greatest of the pianists, but, of course, I shall never hear him. And now, the incredible has come to pass’. H.W.D.

11- June 13 SYDNEY Town Hall Program 5

SCHUBERT Sonata n°20 in A Major D959 – WEBER Sonata n°2 A Flat Op.39 –

SCHUMANN Davidsbündlertänze Op.6

Sydney Morning Herald (June 14): ‘The program was lighter in calibre than any that had gone before, but nonetheless satisfactory. The Weber Sonata in A Flat Op.39 provided an especially interesting experience. A deep and bodyful work of art, it was obviously not. Yet Schnabel made it endlessly endearing. He made everybody see clearly that, although Weber was to some extend preoccupied with pianistic devices, the means rather than the intellectual end, he accomplished his aim with unfailing taste and true musical feeling. The caressing delicacy of melody, the enormous sweep and colour of the sonorities, which made the Weber so joyous has been exemplified earlier in equal measure in Schubert posthumous A Major sonata. How gently, almost casually, the player stated the opening theme! One was hardly aware that he had begun to play so lightly, so meditatively, did the tiny tune express itself. The second movement was memorable in its concentrated simplicity diversified in sudden blazes of temperament. The interpretation of the Schumann was more steadily open to question than anything Schnabel had done during this season. Parts of this fragmentary series had an ineffable lightness, a caprice and fancy that were completely persuasive. Yet at other times , an air of serious introspection seemed to mist over the true waywardness of Schumann’s thought. Still, the general effect of the ‘David Society’ dances was supremely brought. It was an inspiring conclusion to the recital.

Letter to Mary Foreman (June 15): ‘I have now, the first time in Australia, four concert- and journey-free days, the heaviest work is done with a fairly average accomplishment, Eleven appearances, five recitals in Sydney, twenty-five big works performed, many of them for the first time here; now many repetitions will come, but still seven to ten pieces not yet played. In a way, I feel bored by the idea of repeating items; to play another program at each concert is much more attractive, but there is of course a limit’.

With this one-week pause, the next concert took place in Adelaide, on June 20.

_________________________________

They had six concerts together, so Schnabel and Szell had ample time to meet and socialize!

_________________________________

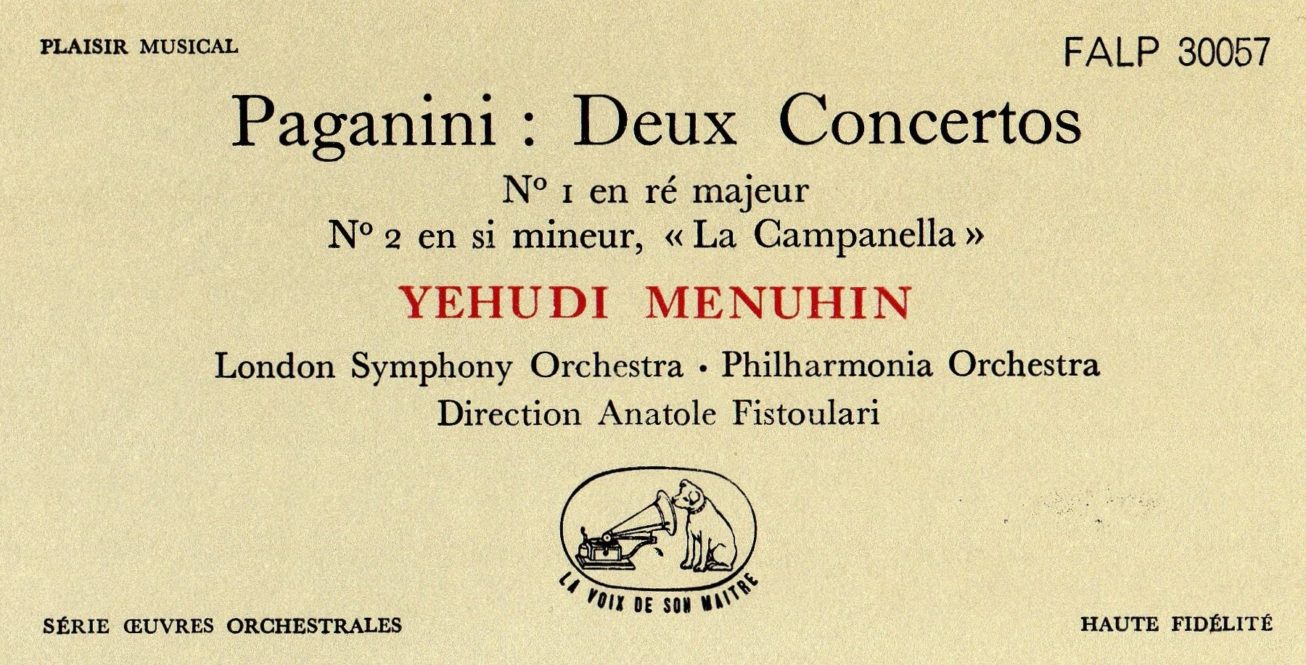

Niccolo Paganini

Yehudi Menuhin – Anatole Fistoulari

Concerto n°1 Op.6

London Symphony Orchestra (LSO)

London Abbey Road Studio n°1 – 21 May 1955

Concerto n°2 Op.7

Philharmonia Orchestra

London Abbey Road Studio n°1 – 3 October 1950

Source 33t /LP: FALP 30057

Pour le microsillon, Menuhin a enregistré deux fois les Concertos n°1 et 2, une première fois avec Anatole Fistoulari (en 1955 avec le LSO pour le Concerto n°1, et en 1950 avec le Philharmonia pour le Concerto n°2), et ensuite en 1960 avec le Royal Philharmonic (RPO) et Alberto Erede. Il a également gravé le Concerto n°1 du temps des 78 tours, en 1934, avec Pierre Monteux et l’orchestre Symphonique de Paris (OSP). L’éditeur a le plus souvent privilégié l’enregistrement stéréo avec Erede, alors que Fistoulari, chef méconnu, s’avère être le partenaire idéal. Avec la chaleur expressive de Menuhin, les interprètes nous font la démonstration que jouer ces deux œuvres n’est pas juste une question de pure virtuosité, mais qu’elles ont bien plus de substance qu’on ne le pense habituellement. De plus, les prouesses vertigineuses que Paganini demande au violon s’accompagnent d’une sorte d’ ’ébriété musicale’ qui l’apparente à Berlioz.

Anatole Fistoulari

Anatole Fistoulari

In the LP era, Menuhin made two recordings of the Concertos n°1 and 2, the first with Anatole Fistoulari (in 1955 with the LSO for Concerto n°1, and in 1950 with the Philharmonia for Concerto n°2), and later in 1960 with the Royal Philharmonic (RPO) and Alberto Erede. He also recorded the Concerto n°1 in the 78 rpm era, in 1934, with Pierre Monteux and the Orchestre Symphonique de Paris (OSP). Publishers have usually favoured the stereo recordings with Erede, but Fistoulari, an underrated conductor, is the ideal partner. With Menuhin’s expressive warmth, the performers show us that playing these two works is not just a matter of pure virtuosity, but that they have much more substance than is usually thought. Moreover, the dizzying feats that Paganini demands of the violin are accompanied by a kind of ‘musical inebriation’ that makes him somehow akin to Berlioz.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

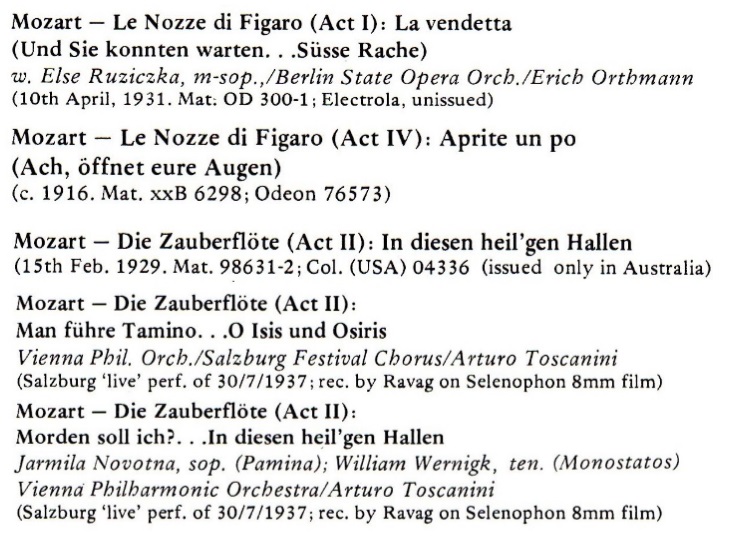

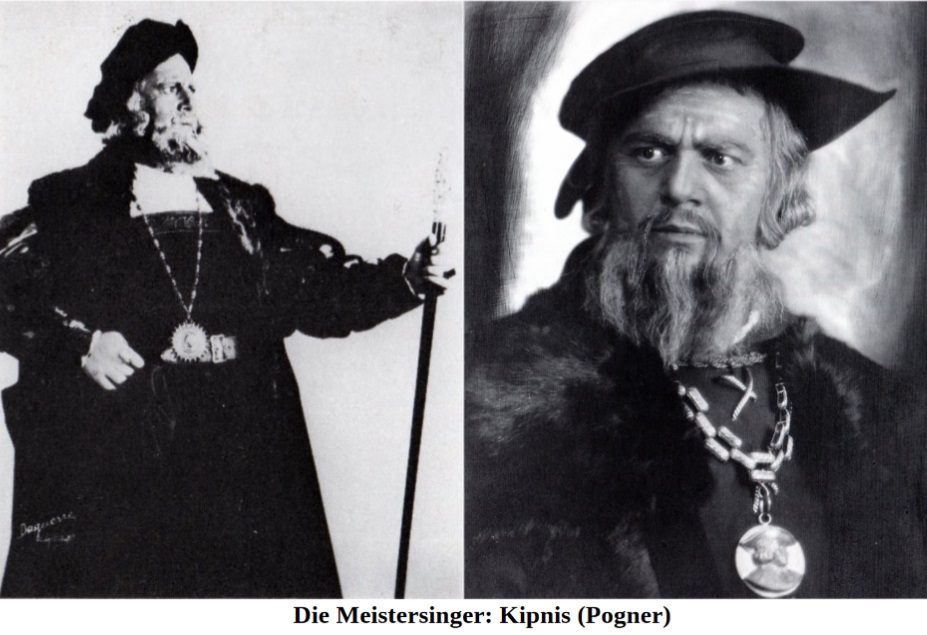

Kipnis – Mozart Verdi Wagner 1916-1937

Alexander Kipnis: Airs d’Opéra /Opera Arias

Source 33t/LP: Pearl GEMM 277/8

Le Nozze di Figaro: Kipnis (Figaro)

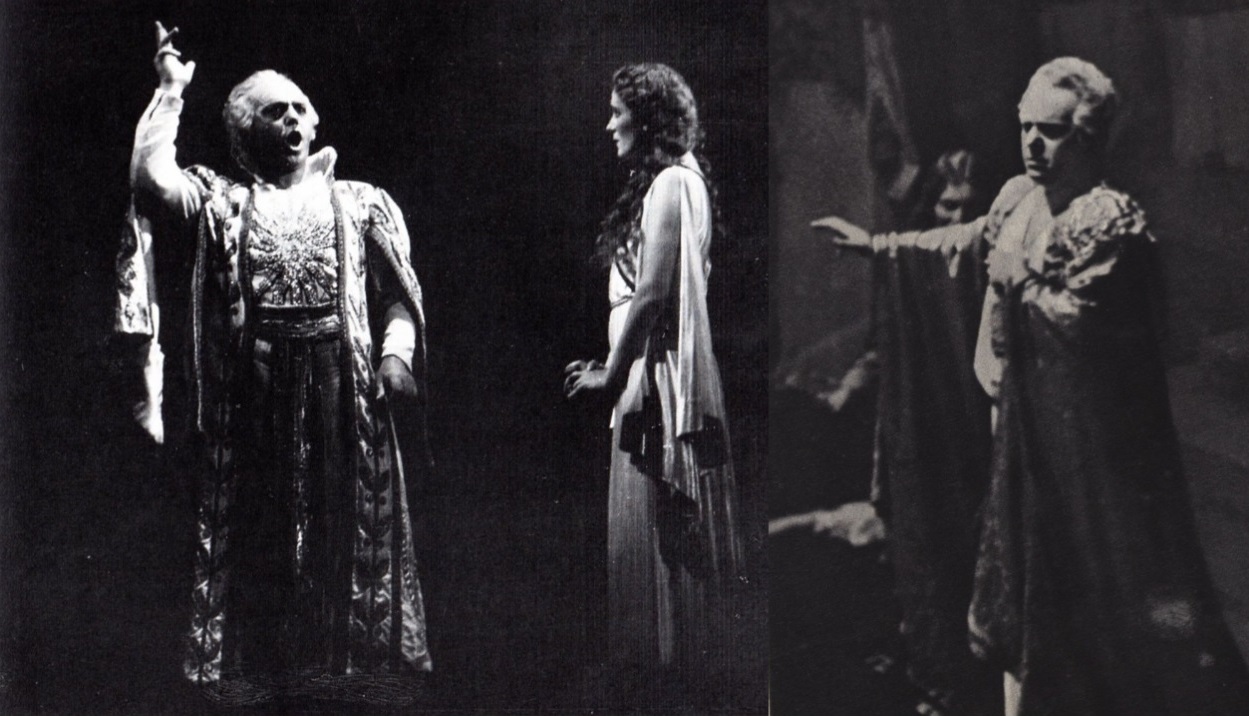

Die Zauberflöte: Kipnis (Sarastro) 1937: Salzburger Festspiele (avec/with Jarmila Novotna)

Die Zauberflöte: Kipnis (Sarastro) 1937: Salzburger Festspiele (avec/with Jarmila Novotna) – Wiener Staatsoper

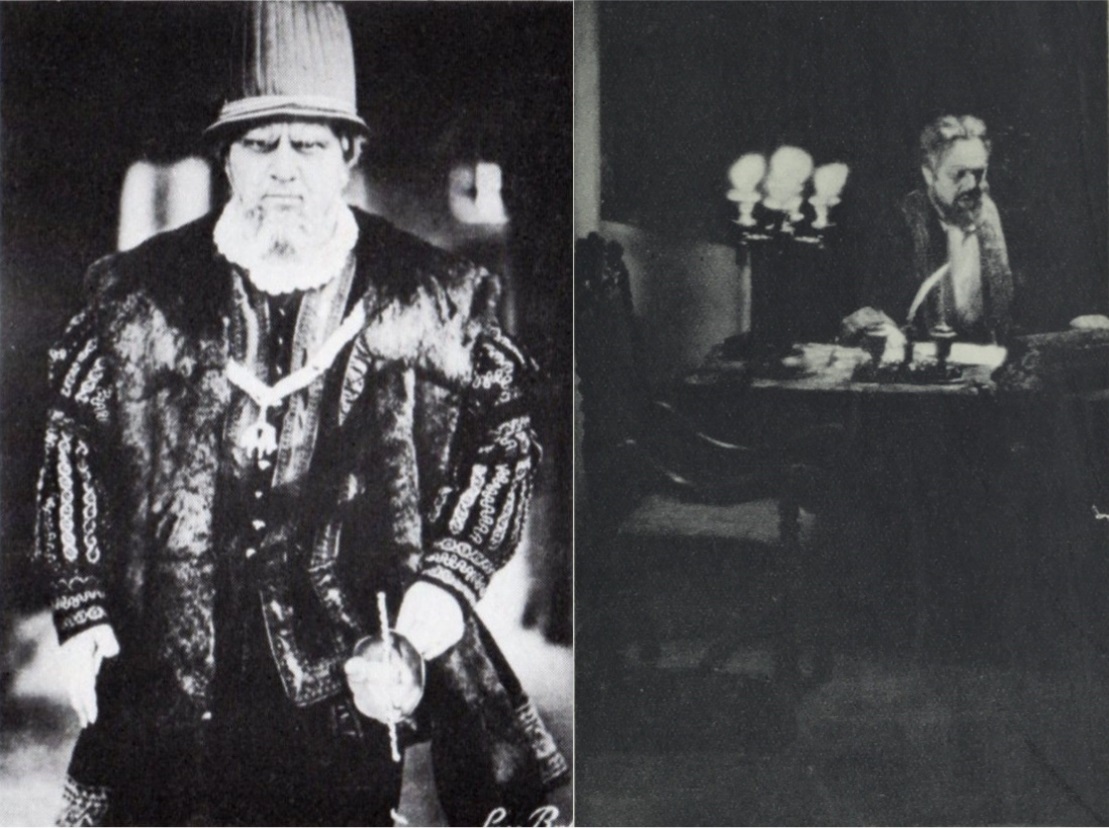

Don Carlos: Kipnis (Philipp II): Berlin (1931) – Wiener Staatsoper (1937)

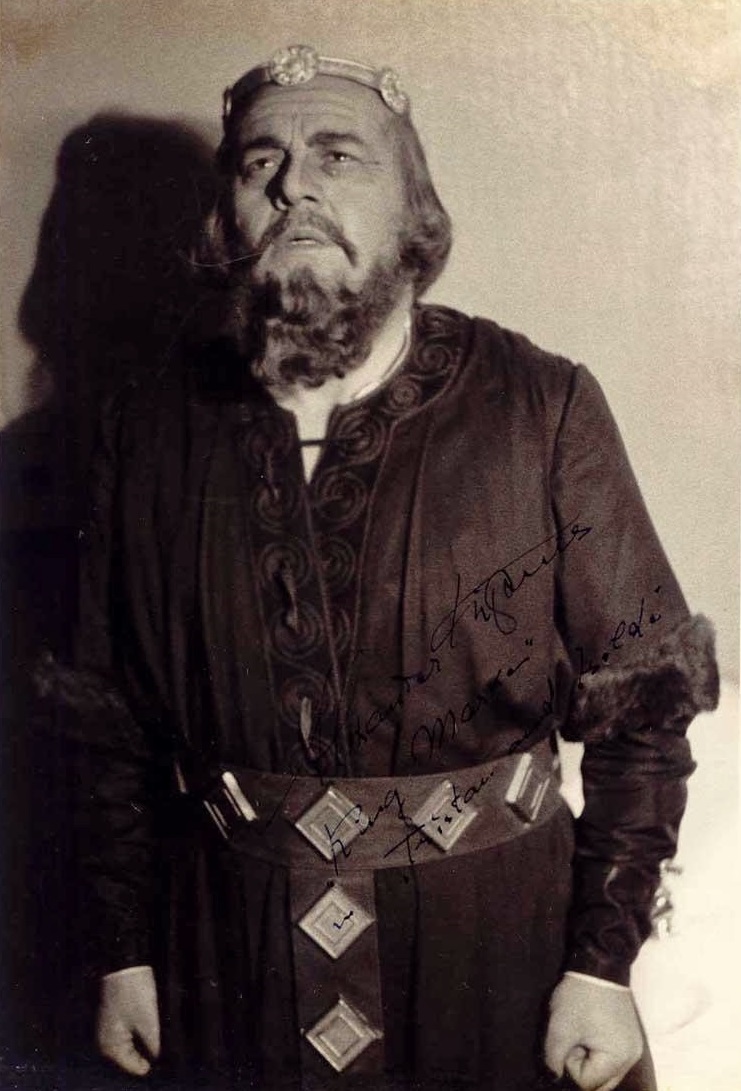

Tristan und Isolde: Kipnis (König Marke)

En 1984, la firme Pearl a publié un Album de deux disques 33 tours (GEMM 277/8) consacré à Alexander Kipnis (1891-1978). Le producteur était le fils du chanteur, le claveciniste Igor Kipnis, et il a fait appel aux services de la ‘Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings’. La sélection d’enregistrements effectués entre 1916 (au moment où Kipnis avait été engagé par l’opéra de Hambourg), et 1937 (juste avant ses dernières apparitions en Autriche), nous montre d’une part, qu’en 1916, la voix possédait déjà l’essentiel de ses qualités, et d’autre part, qu’elle a toujours été extrêmement phonogénique, au point que même les enregistrements les plus anciens restituent son timbre et ses nuances d’interprétation. Il faut dire que le soin apporté aux reports y a certainement sa part.

La présente sélection d’airs d’opéras montre tout d’abord Kipnis dans trois rôles de Mozart qu’il chante en allemand, à savoir Bartolo avec l’air ‘la Vendetta’, Figaro avec l’air ‘Aprite un po’, et enfin Sarastro, dont les deux airs sont donnés dans l’enregistrement public du Festival de Salzburg 1937 sous la direction de Toscanini. L’air ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’ bénéficie également d’une version enregistrée aux États-Unis en 1929 sous la direction de Robert Hood Bowers. Ce ‘doublon’, au tempo plus modéré, permet de mieux rendre compte de l’interprétation de Kipnis qu’avec le tempo rapide choisi par Toscanini.

De Verdi, Kipnis chante dans la langue originale l’air de Procida de ‘I Vespri Siciliani’, ainsi que deux versions de l’air de Fiesco ‘Il lacerato spirito’ de ‘Simon Boccanegra’(1921 et 1931), alors que pour l’air de Philippe II ‘Ella giammai m’amo’ de Don Carlos, la première de 1922, sur deux faces de 78 tours est en allemand, et la deuxième, réalisée l’année suivante, est abrégée et dans un tempo un peu trop rapide, mais est cette fois dans la langue originale.

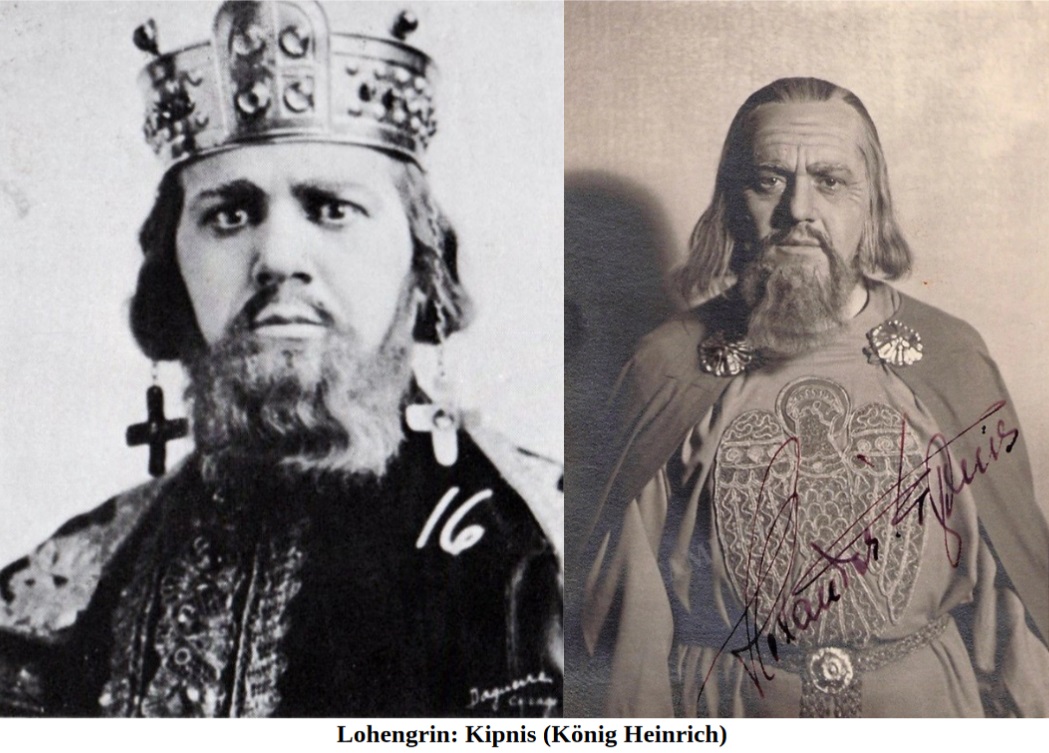

Le programme Wagner débute par l’air du roi Heinrich ‘Gott gruss’ Euch, liebe Männer von Brabant‘ de Lohengrin, rôle que Kipnis chanta 85 fois de 1915 à 1936, avec ensuite l’air du Roi Marke ‘Tatest du’s wirklich’ de Tristan und Isolde‘ (1916), rôle qu’il a chanté pour la première fois en 1917 à l’Opéra de Wiesbaden, et qui l’a accompagné tout le long de sa carrière. Deux airs des Meistersinger ‘Das schöne Fest, Johannistag’ (Pogner) et ‘Verachtet mir die Meister nicht’ (Sachs) font suite et pour conclure nous avons les Adieux de Wotan ‘Leb’ wohl, du kühnes…’. Les deux derniers airs bénéficient de la direction de Leo Blech, alors Generalmusikdirektor (GMD) du Berliner Staatsoper.

____________

In 1984, Pearl released a two-disc LP album (GEMM 277/8) devoted to Alexander Kipnis (1891-1978). The producer was the singer’s son, harpsichordist Igor Kipnis, and he called on the services of the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings. The selection of recordings made between 1916 (when Kipnis was engaged by the Hamburg Opera) and 1937 (just before his last appearances in Austria) shows us that, in 1916, the voice already possessed most of its qualities, and that it has always been extremely phonogenic, to the extent that even the oldest recordings reproduce its timbre and the nuances of the interpretation. It has to be said that the care taken with the transfers has certainly played its part.

The present selection of opera arias first shows Kipnis in three Mozart roles that he sings in German, namely Bartolo with the aria ‘La Vendetta’, Figaro with the aria ‘Aprite un po’, and finally Sarastro, both arias of which are given in the public recording of the 1937 Salzburg Festival conducted by Toscanini. The aria ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’ was also recorded in the United States in 1929 under Robert Hood Bowers. This ‘duplicate’, at a more moderate tempo, gives a better account of Kipnis’s interpretation than the one with the fast tempo chosen by Toscanini.

Kipnis sings Verdi’s Procida aria from ‘I Vespri Siciliani’ in the original language, as well as two versions of Fiesco’s aria ‘Il lacerato spirito’ from ‘Simon Boccanegra’ (1921 and 1931). In the case of Philip II’s aria ‘Ella giammai m’amo’ from Don Carlos, the first, from 1922, on two 78-rpm sides is in German, and the second, made the following year, is abridged and with a rather too fast tempo, but this time in the original language.

The Wagner programme opens with König Heinrich’s aria ‘Gott gruss’ Euch, liebe Männer von Brabant’ from Lohengrin, a role that Kipnis sang 85 times between 1915 and 1936, followed by King Marke’s aria ‘Tatest du’s wirklich’ from Tristan und Isolde’ (1916), a role he sang for the first time in 1917 at the Wiesbaden Opera House and that accompanied him throughout his career. Two arias from the Meistersinger ‘Das schöne Fest, Johannistag’ (Pogner) and ‘Verachtet mir die Meister nicht’ (Sachs) follow and to conclude we have Wotan’s Farewell ‘Leb’ wohl, du kühnes…’. Worth mentioning is that the last two arias are conducted by Leo Blech, then Generalmusikdirektor (GMD) of the Berliner Staatsoper.

Les liens de téléchargement sont dans le premier commentaire. The download links are in the first comment

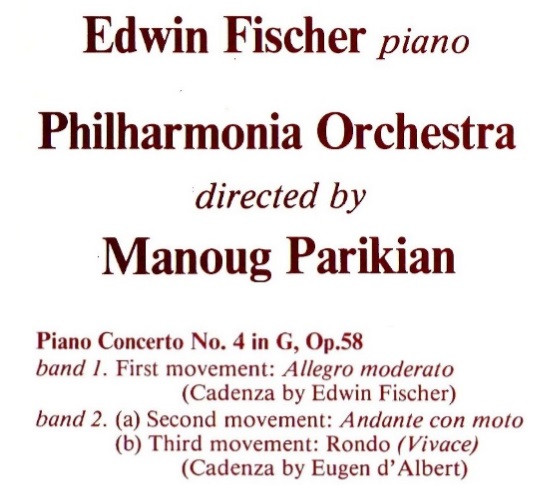

Edwin Fischer – Philharmonia Orchestra

Beethoven Concerto n°4 Op.58

London Abbey Road Studio n°1 – 4,9 & 14 Mai 1954

Prod: Walter Legge & Walter Jellinek – Eng: Douglas Larter

Source 33t/LP: RLS 2900013 ‘HMV Treasury’

Entre le 3 et le 20 mai 1954, Edwin Fischer a entrepris une importante série d’enregistrements à Londres, dont trois Concertos avec le Philharmonia Orchestra.